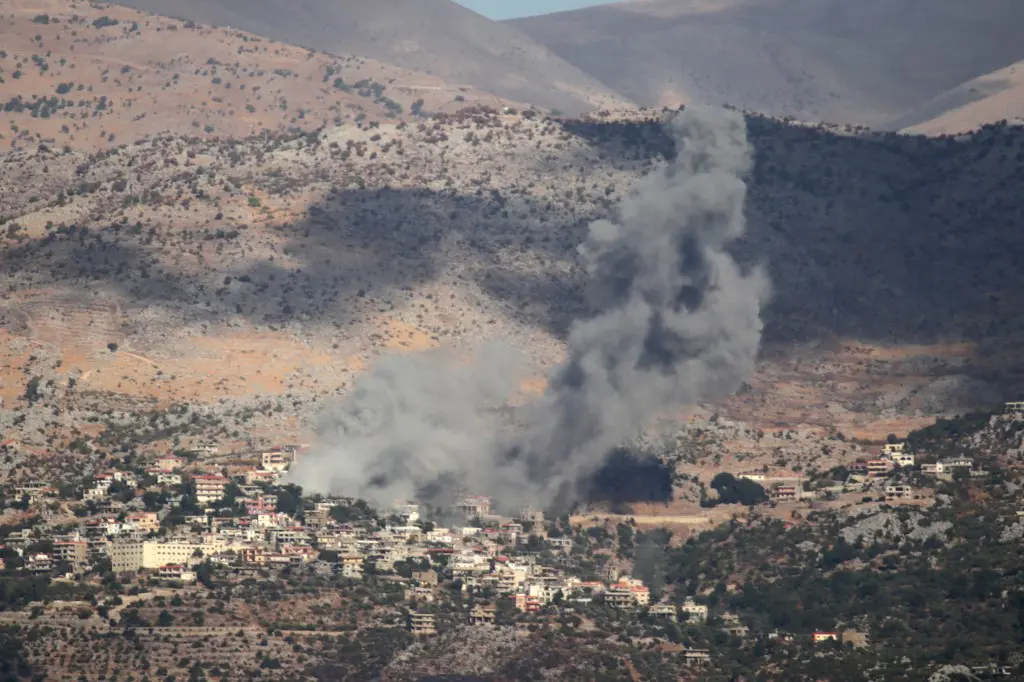

The struggles of education in South Lebanon, exacerbated by war and economic collapse, have severely disrupted the aspirations of many young people, highlighting the dire state of education in the region. Israeli attacks on Lebanon dramatically escalated this week, mostly in southern Lebanon, leading to an increase in fighting along the Israeli-Lebanese border.

Dana Hourany

Aya, 18, is preparing to leave Lebanon, with her flight scheduled for October 10th. As she assembles her life in the run-up for her new life in Belarus, she says she still has much to anticipate.

Aya had initially planned to study pharmacy in Lebanon, but that no longer seems possible.

“I tried my best to find alternative solutions but nothing came up,” she told Fanack.

Like many students from southern Lebanon, Aya had several difficulties after graduating from high school this year, including online study, hazardous roads, lack of transportation, and persistent Israeli aggressions in her region. Senior students, in particular, have had to deal with the added pressure of state official exams, which are mandatory for university admission. Despite calls for canceling them, Education Minister Abbas Halabi insisted on holding the exams nationwide.

Although Aya did well on her exams, she laments not being able to follow her true passion.

“Private universities are very expensive, and I, unfortunately, was not admitted to the Lebanese University – the only public university in Lebanon,” she said.

Her father, once successful in the construction business, is now unemployed. The family, originally from the border village of Meiss al-Jabal, has been displaced and now resides in Shaqra, south Lebanon. Aya notes that her uncles abroad help cover the family’s expenses.

“My uncle, who lives abroad, said he’ll pay for my tuition in Belarus, which is how I am able to pursue my education,” she said, noting that she shifted her focus towards dentistry.

Aya is one of many students whose dreams have been altered by the war in south Lebanon, which has caused immense devastation with over 2,500 casualties, and around 600 deaths, including 137 civilians, in addition to 274 deaths on Monday alone. Upon the arrival of the new school year, there appears to be minimal progress, forcing educators and learners to devise innovative coping strategies independently.

Israeli attacks on Lebanon dramatically escalated this week, mostly in southern Lebanon, leading to an increase in fighting along the Israeli-Lebanese border. Thousands of people fled, jamming Beirut’s major roadway. According to the Health Ministry, the attacks caused at least 1,024 injuries.

Back to School

In Lebanon, the academic year normally starts in September or October, with public schools commencing later than private ones. The commencement of this school year coincides with the eleventh month of Israel’s continuous offensive against southern Lebanon, which began a day after Hamas launched a surprise attack on Israel on October 7.

The prospects of education in Lebanon’s border regions are still uncertain; schools may have to resume offering online classes, just like they did the previous year. However, a few villages have exceptions.

Aya’s youngest brother and her three sisters, who are in grades 7, 8, and 11, are still enrolled in school. Doja and Ali, her younger siblings, are anticipated to attend in person. Ali in particular is beginning his first year of private school in a nearby border village.

“Given that they are still in the most formative years of their schooling and that in-person instruction is necessary, this is the best-case scenario. This is especially true for my youngest brother Ali, who can’t possibly go through his debut school year via screen,” she said.

The village in question, still shows signs of life, with people either remaining or returning after being displaced. According to Aya, schools there will be open as usual. But with Israel’s escalation, there is no telling.

“I guess there is a consensus on which villages are most targeted and which are not, but now nothing is certain,” she explained.

The school the family is thinking of attending in the border village was closed last year and switched to distance learning.

“Of course, we worry about how dangerous the roads will be when it comes to transportation to and from school, but we rely on God for protection,” Aya said.

Her other two sisters, Lea and Lynn, will most likely attend a public school near their current home in Shaqra. However, one challenge remains: their old school in Meiss el-Jabal has refused to provide the necessary paperwork for their enrollment in a new school.

“It’s because we didn’t pay last year’s tuition, so we cannot enroll them in school just yet, and we are still figuring things out,” she said.

Although Hezbollah has been providing monthly financial aid to the family, Aya notes that there has been no specific assistance for education. However, she has heard rumours that Hezbollah might soon address this.

Many families have yet to register their children in school, uncertain whether classes will be in-person, online, a mix of both, or none at all. Additionally, parents are grappling with the high cost of purchasing books and stationery, which has become a significant burden as many displaced families from the south have lost their primary sources of income. As a result, parents are hesitant to make such a costly investment without knowing for sure if schools will even open.

Little to No Options

Rima, 24, originally from the border village of Beit Lif and now living in Tebnin, spent last year helping her younger sister, Nour, 12, study online.

This year, the family hopes to enroll Nour in a nearby public school for in-person classes. However, the school has indicated it may not take additional students as its classrooms are full. Instead, the school might start an afternoon schedule for displaced students.

“This is not something my sister wants to do,” Rima told Fanack. “She’s used to her normal 8 a.m. to 2 p.m. schedule, and it will be difficult for her to adjust.”

Rima emphasised the importance of considering children’s mental health, especially given the psychological toll the war has taken on everyone. Sonic booms, nearby shelling, the sound of constant drones, and rocket fire have left many students in southern Lebanon struggling with depression and anxiety.

“My sister was definitely affected, and I feel she’s more agitated and angrier than before,” Rima explained. She noted that she had to put in extra effort to keep her sister focused, as the war impacted her concentration and motivation.

Like Aya’s family, Rima’s family is also facing difficulties enrolling Nour in a new school due to unpaid fees from her previous school in Aita el-Shaab, a border village still suffering from heavy damage and bombing.

“I called the school and told them we can’t pay all the money at once, and their answer was to borrow money,” Rima said with a slight laugh, adding in disbelief, “We’re all in the same boat, we’re all displaced and suffering from the war!”

To set up a payment schedule, she intends to contact the director of the institution. “We are not sure what to do if she doesn’t accept,” she said in a somber tone.

Although Rima hopes online learning will not be necessary this year, she is prepared to support her sister again if it comes to that. “I can’t imagine how it is for other students who don’t have someone to help them with online learning because it really is difficult for children to focus and take in the material,” she explained.

She also hopes that going back to in-person classes will help her sister regain a sense of normalcy by making friends and socializing. For now, their lives are filled with uncertainty. They don’t know which school Nour will attend, they live in a rented house and are unsure if the landlord will reclaim it at any point, and both parents are currently unemployed.

“We receive aid, but it’s not enough,” Rima said, noting that a charity provided them with free stationery last year, which Nour will reuse. However, they plan to buy second-hand books to save on costs.

A Wasted Year

Aisha el Haj Hassan, 19, originally from Meiss el-Jabal, has taken shelter in Baalbeck. Her father is originally from Syria, but they had lived in Meiss el-Jabal for over 10 years.

“We feel the same suffering as the southerners; we are in this together,” Aisha told Fanack.

Aisha graduated this year after completing her final year online, but she won’t be able to attend university.

“I can’t afford nearby private universities, and the closest Lebanese University is in Zahle, an hour away, which would require expensive transportation,” she said.

Her father recently found a new job packing produce after months of unemployment, but it barely covers basic expenses like food and rent. Aisha had dreamt of becoming a lawyer, driven by a desire to defend women’s rights and vulnerable groups. However, this dream now feels distant. Her only option might be to enroll in a nearby institute to study business, the closest field to law.

“But if the tuition is too high, I might not be able to do that either,” she said, her voice quivering with sadness.

Her parents have already told her she may not be able to continue her education this year, a reality she’s struggling to accept.

“It was my dream to live the university life, to be with my friends and attend classes in a subject I’m really passionate about,” she said. “You know, to feel like we are finally adults!”

After pausing, she added with a grieving tone, “Honestly, there’s a lot of pain. I really wanted to be a lawyer with an impact; education is really important to me.”

Unlike Aya and Rima, Aisha’s family has only received financial aid twice at the beginning of the war. She is unsure if the lack of aid is related to their Syrian background. Her younger siblings, aged 14, 15, and 7, will all be studying online, as transportation to nearby schools is not an option.

In addition to the war, Lebanon is still struggling with an economic crisis, which caused the Lebanese pound to lose more than 98% of its value against the dollar, leaving many unable to access their dollar bank accounts.

Aisha fears most for her youngest brother’s future, as his formative years are being spent in online learning, with teachers sending him videos on spelling and basic language skills. She’s not sure how much he’s getting out of it.

“I’m not confident that things will improve now that my objective has been pushed back. We students may not be able to study for years to come. Many of my friends are in the same situation,” she said.

From the Educator’s Perspective

Sawsan Ghanawi, a sociology teacher at Mohammad Falha highschool in Meiss el-Jabal, told Fanack she expects online learning to be more organised this year, as last year they had little time to prepare.

“Decisions were made on the spot, and some students moved to houses without internet or electricity,” she said. “So this year, we hope conditions will slightly improve.”

Last year, they didn’t use Microsoft Teams, opting for Google Meet, Zoom, or even WhatsApp for some students, which she admits wasn’t the most effective solution. Despite being satisfied with her senior students’ official exam results, she notes that many faced significant challenges, moving homes frequently, and some even lost their houses or family members in the war.

“Our struggle as public teachers is compounded by the fact that our real salary is around $30 per month,” she explained, adding that they received aid from the Ministry of Education last year, bringing their total to about $400 per month. “But that’s still not enough,” she emphasised.

The Ministry is considering increasing funding to $600 per month, but Sawsan points out that “this is still aid and not a fixed salary, which means it could be stopped at any moment.”

In Lebanon, there is always the possibility of a strike, like in 2023, when public school teachers went on protest for months, leaving just around 50 days of sessions. Before 2019, Sawsan’s salary was $2,000, which is an enormous disparity.

Although she prefers in-person instruction, the mother of three is uncertain about which school to enroll her kids in and worries about transportation from their home in Deir Ntar, south Lebanon.

“There’s also the concern of enrolling them in nearby public schools in case there are strikes,” she added. She also heard some private schools aren’t accepting displaced students, fearing they might leave once the war ends.

Sawsan feels that the Ministry of Education gives preference to private schools over public ones and that more work should be done to improve public education administration, particularly in these trying times. Despite her dedication to enhancing her curriculum and making better preparations for this year’s online lessons, she laments her absence from her pupils.

“Especially the senior ones—I used to feel like they were my children,” she said, her tone heavy with sadness. “It was really sad that I didn’t get to say goodbye to them when they graduated.”

Her bond with her students makes it hard to connect solely through screens, as she thrives on in-person interactions. There are new students she wishes she could personally meet but for now screens are all they have.

“We wish students and their families the best of luck and hope that the war doesn’t become any worse. And as educators, our goal is to carry out our responsibility and support our pupils through this extremely difficult period,” she said.