State Borders

Yemen is a populous, mountainous country at the southern tip of the Arabian Peninsula.

It is the southernmost country of the Middle East, bordering Saudi Arabia on the north and Oman on the east.

In the south, its coastline stretches more than 1,000 kilometres along the Gulf of Aden, extending east to the Arabian Sea (or Indian Ocean); to the west, the narrow yet dangerous Red Sea separates the country from Africa.

Biogeographically, the western part of Yemen belongs to the Palaeotropics, as do Ethiopia and Eritrea, where the same vegetation and climate are found.

Geography and Climate

Yemen is roughly rectangular, stretching 1,500 kilometres from east to west and 350 kilometres from north to south, and covers an area of 528,000 square kilometres; it is slightly smaller than France, Afghanistan, or Somalia, and slightly larger than Iraq, Spain, or Morocco. Yemen’s northern neighbour, Saudi Arabia, is four times larger, while its eastern neighbour, Oman, is about half its size.

Yemen has several climates. Western Yemen benefits from monsoon rains, which fall mainly in late spring and at the end of summer. Most of the rain falls in the mountains, with an annual maximum of a 1,000 millimetres in the southern mountains, decreasing gradually to an average of 400 millimetres in the northern mountains.

Temperatures in the mountains vary with altitude and season, with an average of 16°C and frosty winter nights in the higher mountains.

The Tihama coastal strip, by contrast, is always hot and is very humid during the rainy season, a climate similar to that across the Red Sea, in Eritrea and Somalia. The eastern desert has a dry climate, with heavy but sporadic rains and frosty nights.

Lowland Tihama

The Tihama is part of the coastal plain bordering the Red Sea. Like the mountain range, it stretches well into Saudi Arabia. The Yemeni Tihama is always hot and, in summertime, humid as well. Fertile, semi-tropical spots are centred on oases and rivers, mostly in the foothills of the mountains.

In some places the Tihama has an African atmosphere, with dark-skinned people living in straw-thatched huts. The plain is home to historic towns, including the former capital Zabid and the port city of Mocha (al-Mukha), from which Dutch traders began exporting coffee in the 17th century.

The modern port of al-Hudayda is the fourth largest city in Yemen.

Peripheral Inhabited Areas

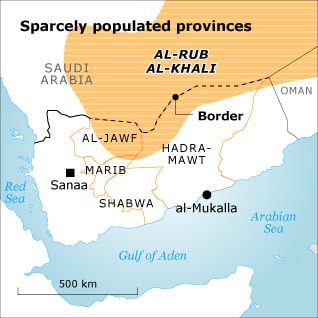

To the east, the mountain range descends gradually into the arid and sparsely inhabited provinces of al-Jawf, Marib, and Shabwa.

With the exception of a concentration of agricultural activity and antiquities around Marib, these extensive provinces derive their economic importance mainly from the oilfields beneath the semi-desert lands.

Still further east, the Hadramawt suddenly appears, an isolated chain of fertile oases cut by canyons. The Hadramawt is associated with a distinct ancient civilization. The governorate of the Hadramawt stretches to al-Mukalla, a large port city on the Arabian Sea, 500 kilometres from Aden.

Yemen shares the Rub al-Khali, or Empty Quarter – a vast desert occupying a large part of the Peninsula – with Oman, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates. It is one of the largest sand deserts in the world and is uninhabitable for people. The Rub al-Khali boasts some of the largest oilfields in the world. It presumably also holds a wealth of archaeological and geological riches, but it has yet to be explored extensively.

Socotra

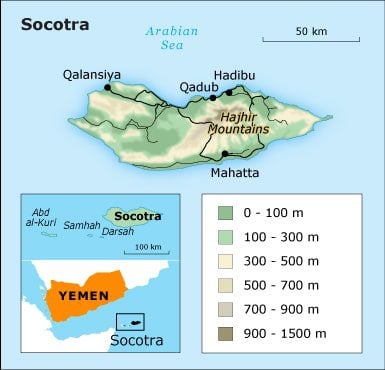

The isolated and therefore long-neglected island of Socotra lies at the maritime crossroads of Africa and western Asia, 800 kilometers south-east of Aden and 250 kilometers north-east of the tip of the Horn of Africa.

The island has an area of about 135 by 40 kilometers and, together with three smaller neighboring islands, is home to nearly 50,000 people. In the 1970s, Socotra was the site of a Soviet military base. Sometimes nicknamed the Galapagos of the Indian Ocean.

Socotra shares some topographical features with other islands off the African coast, such as Cape Verde and the Spanish Canary Islands.

Socotra is becoming a destination for environmental tourism and an important site for the conservation of eco-diversity; much of the isolated island’s rich and remarkable flora and fauna is endemic and unique in the world.

Nature Reserves

Several parts of Yemen have been designated as nature conservation areas. The island of Socotra is by far the most important of them, because of its exceptional number of endemic species.

The mountainous area of Utma, west of Dhamar, is one of Yemen’s oldest designated nature reserves. North-west of Utma lies the national park of Jabal Bura, which preserves Arabia’s last surviving forest, still inhabited by baboons.

These reserves are sometimes inadequately maintained. They often lack financing and are subject to corruption.

An exception is Socotra, which has been ‘adopted’ by a group of scientists, and, through them, by UNESCO, which recognized Socotra in 2008 as a World Natural Heritage site.

Water Crisis

Yemen has one of the highest poverty rates in the world, but among the challenges the country faces, none may be more daunting than that of water sustainability.

Yemen ranks among the world’s most fragile countries in terms of water security. Its underground aquifers are predicted to dry up within a decade as a result of overuse. To promote agricultural development, the government implemented policies that ‘encouraged the use of water, including low-interest loans, cheap diesel and public investment in surface or spate irrigation’, causing excessive water consumption. Wells are being drilled illegally into natural groundwater aquifers and leaky pipes are not maintained properly.

According to a UN report on Water Statistics issued in 2010, Yemen’s total renewable water resource was 2.5 billion cubic meters per year, while the total demand is estimated to be an annual 3.4 billion cubic meters, with 900 million cubic meters per year being extracted from aquifers. Hence, aquifers are declining by one to seven meters per annum, and are rarely recharged because of frequent droughts. Water consumption is thus much higher than natural recharge.

Factors Contributing to the Crisis

The average annual rainfall ranges from 500 to 800 millimeters in the highlands. The aquifers that service most of the inland are barely refilled due to the low volume of precipitation. Water purification and cutting-edge water conservation technology have brought some relief, although many areas in Yemen lack a secure electricity supply and an infrastructure to successfully implement these advanced water technologies.

Climate change is another factor that will affect Yemen’s water availability. According to a 2008 report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the climate in Yemen and the region will become hotter and drier, leading to an increase in the occurrence of droughts. The decrease in the frequency and amount of rainfall in Yemen might endanger the country’s agriculture. The World Bank is raising awareness among Yemeni farmers on how to conserve and use biodiversity to make agriculture less vulnerable to climate change.

Coastal areas like Hodeidah, Mukullah, and Aden might benefit from direct access to seawater, if Yemen had the financial means and the right infrastructure to desalinate seawater. However, desalination is a costly process, and the salt discharge has to be put back into the sea, leading to additional environmental hazards for Yemen’s marine coasts. Even if desalinization facilities are implemented, delivering desalinated water to the mountainous and water-depleted interior is immensely expensive and inefficient.

Another important cause of the water shortage in Yemen is the Qat cultivation that takes up around 60 percent of water used in agriculture and 90 percent of the nation’s groundwater. Prohibiting or scaling back Qat cultivation could save a substantial amount of water. But Qat is an immensely lucrative cash crop in an economy that does not offer many viable alternatives for earning comparable incomes. Unfortunately, the Yemeni government has encouraged Qat cultivation while failing to provide alternatives that could allow farmers to sustain themselves.

Compounded by poverty, illiteracy, and reduced oil production, the precarious water situation has the potential to destabilize the country. The ongoing struggle between the government and the rebels has also severely influenced the water crisis, leading to a humanitarian crisis in some areas of Yemen. Some cities have been cut off from the rest of the country for weeks, as clashes continue, with many roadblocks and checkpoints being set up. UNHCR estimates that 150,000 people have been affected by the Yemen conflict since 2004, including those forced from their homes by the latest round of hostilities.

Lack of Law Enforcement

Over the past fifteen years, Yemeni institutions have invested much effort into new legal and administrative frameworks (new water legislation, establishment of the National Water Resources Authority), studies, and monitoring systems.

An important achievement was the decentralization of water management to a local level. Agricultural technologies were introduced, replacing the traditional farming practices and systems of water management. But the government, with its newly emerging institutions, has failed to prevent the sinking of wells or to regulate groundwater levels.

The Ministry of Agriculture and Irrigation (MAI) is responsible for formulating policies on irrigation, crops, livestock, and forestry production and for coordinating public investment and services in the agricultural sector.

The General Directorate of Irrigation (GDI) is located within the ministry and carries out all the duties related to irrigation, particularly the construction of dams and water harvesting and spate structures.

Most field services are provided to farmers through decentralized Regional Agriculture and Irrigation Offices (RAIO) in the different governorates.

Despite the existence of these institutions, the Yemeni government has failed to fully enforce the law and prevent water wastage. The main reason for this failure is that it is hard to bring water to the top of the agenda in a country faced with so many problems.

New Approaches

Recently, a number of changes have taken place that suggests a larger political will for change. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization, several projects are being run under the supervision of the Ministry of Agriculture and Irrigation to provide various services, particularly the introduction of water-saving techniques and the construction of water harvesting and spate structures.

Other areas of action include wadi bank protection and the rehabilitation of abused terraces, as well as the rehabilitation and maintenance of existing irrigation structures. To support agricultural development at a regional level, three Regional Development Authorities (RDAs) have been established in the northern governorates.

Although RDAs have not been established in the southern governorates, agricultural production in wadis such as Wadi Hadramout, Wadi Tuban, Wadi Beihan has been supported by donor agencies through the Directorates of Agriculture in the respective governorates. In addition to the above authorities, the Agriculture Research and Extension Authority (AREA) is working under the umbrella of the Yemeni Ministry of Agriculture and Irrigation.

The government recognizes the critical water situation in Yemen and is undertaking different actions to deal with it. Several water sector strategies, legislations, and policies have been prepared and implementation of some of them has begun. The Water Law was enacted on 31 August 2002, and amended by the Yemeni Parliament in December 2006. Implementation of this law will give a major boost to the issue of water conservation.

There is no clear solution to Yemen’s water shortages. Water purification, rainwater and grey-water reuse, irrigation efficiency, and conservation technologies are being introduced in Yemen, particularly in the agricultural sector. Such facilities would, in the long run, help curb unemployment, reduce food shortages and lead to a rise in tourism.

A solution to the Yemeni water crisis might be found in the combination of approaches, depending on regional differences, topography, existing water resources, and the local economy.