Introduction

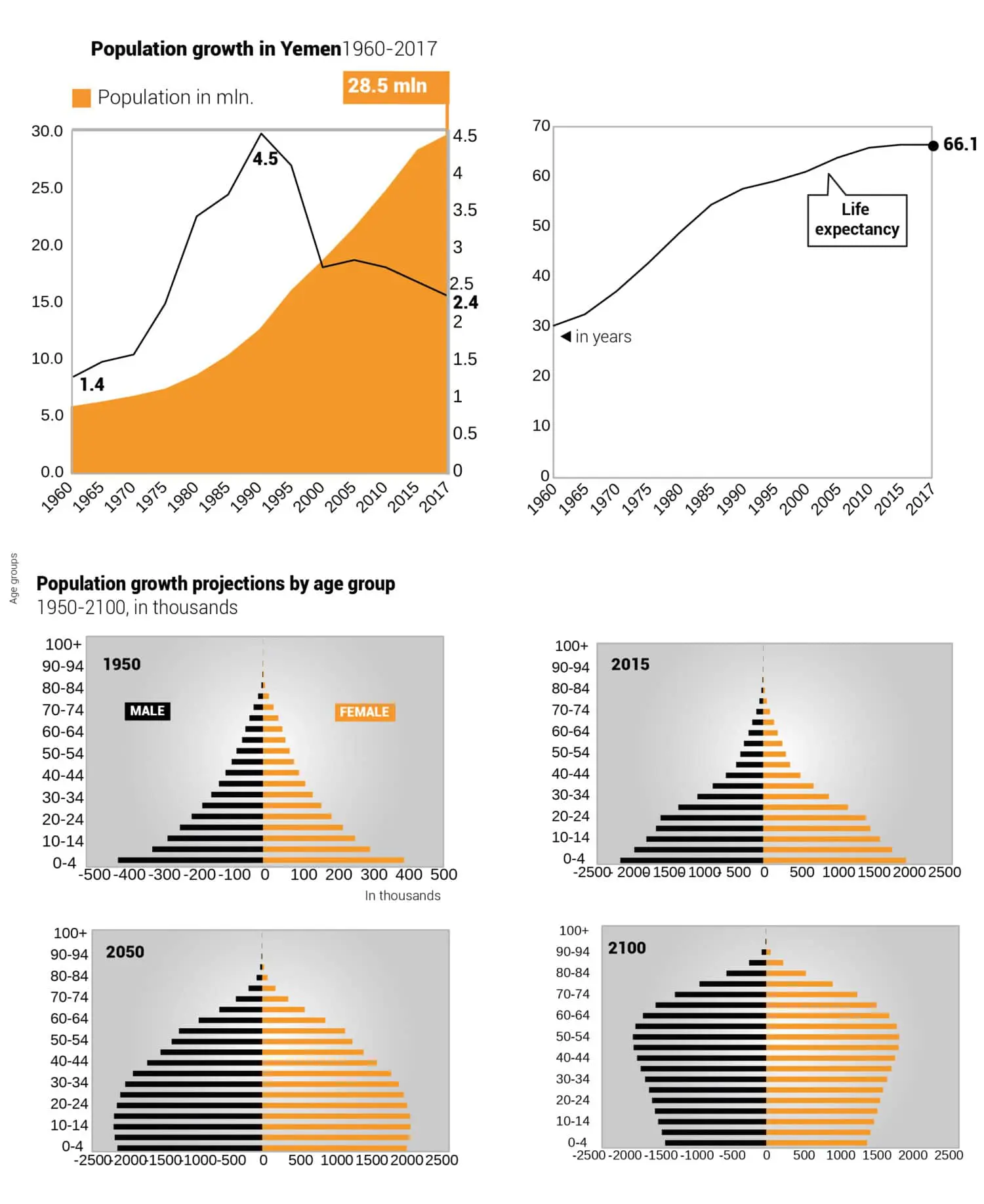

The population of the Republic of Yemen in 2020 was estimated at 29.826 million, according to United Nations estimates, with an average population growth of 2.27% over the population in 2019, which was estimated at 29.162 million. The average population growth rate was in 2015.

The population of Yemen is distributed by gender in 2020 AD, at 50.37% for males, 49.63% for females (15.024 million males and 14.802 million females), and a gender ratio of 101.5 males for every 100 females.

The number of refugees of concern to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) is estimated at 3.923 million. The number of international migrants (arrivals) is estimated at 385.6 thousand immigrants (arrivals), despite the tragic conditions the country has been experiencing since the outbreak of the war in 2015 and the start of the two military operations. Al-Hazm “and” restoring hope “to a Gulf coalition led by the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia against the Houthi rebels, to stop their advance towards the city of Aden, in the south of the country.

Population statistics in Yemen are modern, as they did not begin until the 1970s. The estimates that preceded these statistics indicated that the population of Yemen was 4.3 million in 1950 AD, and it increased to 5.2 million in 1960 AD, 6.3 million in 1980 AD, then to 12.2 million in 1988 AD. In the 1994 census, the population of Yemen was 15.83 persons.

In the last census conducted by Yemen in 2004, the population of Yemen was approximately 19.685 million. From that, we see that Yemen witnessed a great leap in the last quarter of the twentieth century. After the population growth rate between 1965-1970 was about 1.61%, it rose to 1.98% for the period 1970-1975 AD and to 3.7% during the period 1988-1994AD. This steady increase in the number of the population is attributed to the tendency of the death rate to decrease at 11.4 per thousand and the high fertility rate of 7.4 births per woman at that time.

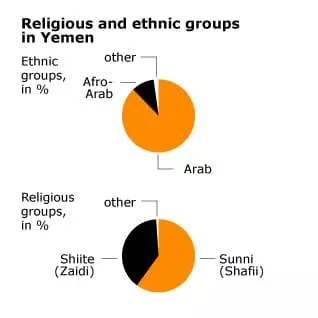

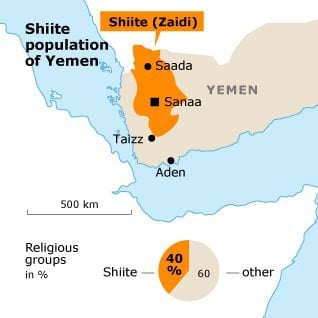

Muslims constitute 99.1% (65% of the Sunnis, and 35% of the Shiites) of the total population of the country, while 0.9% include Jews, Baha’is, Hindus, and Christians. Many of them are refugees or temporary foreign residents (2010 estimates).

Arabic is the official language of the country, as well as the Socotra dialect that is widely used on the island of Socotra and the archipelago, in addition to the Mahri dialect widely used in eastern Yemen.

Population Growth

Source: https://www.citypopulation.de/Yemen.html. @FanackThe average Yemeni family produces many children. In fact, Yemeni women were, for decades, the most fertile in the world, bearing an average of more than seven children. Only since 2005 has this number dropped, to a low of 4.7 in 2010, which still gives a growth rate of 2.7 percent, down from 4.7 percent in 1990. This was achieved after a long and broad national campaign for birth control, supported by tribal elders and influential religious leaders. Today, the average number of children per family in towns is decreasing. However, birth control is still very controversial in remote mountain villages. Because many Yemenis live in isolated rural areas, the population growth rate remains high and will continue so for many years to come.

Age Groups

Estimates in 2018 indicate that about 39% of the total population is under the age of fifteen, while 54% of the population falls between the age group 15-54, while only 4% fall in the age group 55-64, and about 3% of 65 Years and older.

The total fertility rate for the year 2020 was 3.8 births per woman, and the average life expectancy was 66.05 years (64.4 years for males, 67.7 years for females).

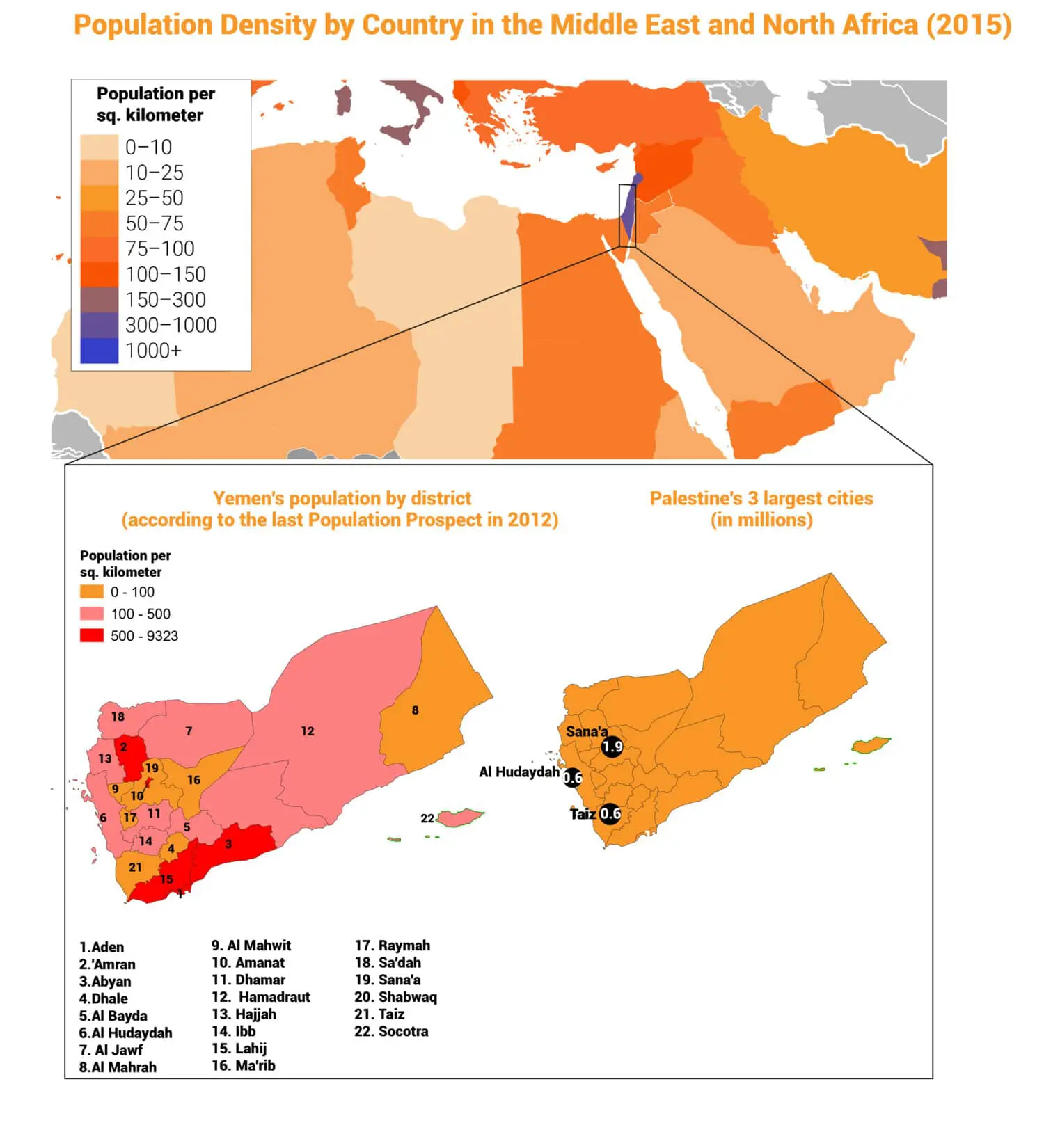

Areas of Habitation

The population density in Yemen was about 56.5 people / km2, in 2020 AD, the capital, Sanaa, accounts for 2.87 million people of the total population of the country, and the percentage of the urban population is 37.3 percent in 2020.

The majority of the population is located in the Asir Mountains (part of the larger Sarawat mountain range), located in the far west of the country.

The Republic of Yemen has divided administratively into twenty governorates, and it is divided into 286 districts. There are 109,936 villages and cities, according to the National Population Council.

There are 115 islands, the largest of which is Socotra, which is located in the Arabian Sea, with an area of 3500 km2, followed by Kamaran Island, which is located in the Red Sea.

Ethnic and Religious Groups

The Yemeni population is very homogeneous. Nearly all Yemenis are believed to be ethnical of southern Arab origin and are traditionally considered descendants of Qahtan (although through the centuries they mixed with Persians, Indians, and others). Southern Arabs are considered – in local genealogical tradition – to be ‘purer’ Arabs. Many Arabs regard Yemen as their (sometimes distant) land of origin. There is also a small minority of (Shiite) Ismailis. There used to be many Jews, but the present Jewish community numbers only a few hundred.

The qabila, or tribe, is of major importance in Yemen. Tribes adhere to Sunni (Shafii) Islam or Shiite (Zaidi) Islam. All Yemenis – with the exception of new immigrants and the Akhdam (Yemen studies mention several other terms for these non-tribal people, including duafa, masakin, and mustadafin, meaning weak, poor, and vulnerable people) – are tribal, in varying degrees; southern Yemenis are much less so than northerners.

City inhabitants also call themselves tribal, for the qabail (the plural of qabila) is a source of both historical pride and present-day identity. People sometimes find it helpful to refer to their tribe in order to get elected, to be protected, to find a job, or even to get permission to build a house. The tribes, therefore, dominate Yemeni politics.

Legend has it that Yemen was founded by Qahtan, the father of the southern Arabs. Qahtan is said to be the father of Yemen and the forefather of Saba, eponym of the kingdom of Saba (Sheba). Saba had two sons, Himyar and Kahlan. After the fall of the kingdom of Saba, the tribes spread from the Marib plateau to settle in the western mountains. Yemeni tribes are not nomadic but are sedentary communities of people bound to their agricultural territory.

Tribalism has diminished in the southern mountains, where conditions are less harsh than in the north. The south has often been ruled by outsiders, in modern times by the British Empire. Because farming opportunities in the north were far less favourable, northerners have, in the past, often migrated to the south or beyond the Peninsula. Although these migrants retained the memory of their ancestry, many of their tribal practices were lost in the migration.

Some North African Berbers believe they are directly descended from the Yemenis. Many Saharan tribes claim descent from the Banu Sulaym, who originated from Yemen and Saudi Arabia. The Lamtuna, a Berber nomadic tribe of the western Sahara, claims descent from the old South Arabian kingdom of Himyar. Islamic Seville (called Ishbiliya) was governed by Yemeni Arabs descended from the Banu Lakhm.

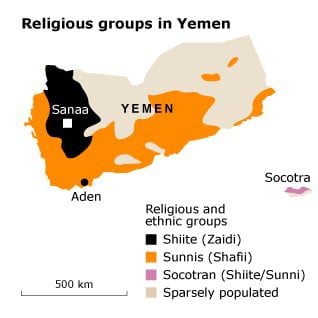

The Zaidi Stronghold and the Crown Colony of Aden

The Zaidi imams ruled northern Yemen from 873 until 1962, after local tribes invited the first Zaidi imam to come and settle tribal disputes. The Zaidi imam heads a Shia sect, referred to as ‘Fivers’, followers of Imam Zayd. They briefly established states in northern Iran, but their stronghold was in Yemen. From the 9th century onwards, the Zaidi imams were a constant factor in Yemeni politics, at times extending their rule as far as Taizz.

The Zaidi imams, who were theocrats rather than military leaders, never fully controlled the northern Yemeni tribes. During the eleven centuries of their rule –during which they moved the capital back and forth from Saada to Sanaa and on to Taizz – tribal revolts broke out frequently across the country. In the south and in distant Hadramawt, smaller dynasties, tribes, and sheikhs contested Zaidi rulership.

In the 19th century, the Ottomans returned briefly to power, but they too failed to rule the entire country. In the north, Zaidi tribes easily held out against the Ottomans, while the Crown Colony of Aden and its protectorates, in southern Yemen, had, since 1839, been in the hands of Great Britain. The British controlled Aden and its immediate surroundings in order to secure strategically located Perim island in the Bab al-Mandab – the entrance to the Red Sea –and with it the important sea route to Asia. Aden also possessed a natural port, where long-haul ships could refuel. British rule did not extend much beyond Aden, where they entered into an alliance with local sheikhs, called Ingram’s Peace.

The Ottoman Empire perished after its defeat in World War I. Yemen was then already governed by a Zaidi imam, Yahya, with the exception of the Crown Colony of Aden, which was controlled by the British. He and his successors ruled the country under the name of the internationally recognized Mutawakkilite Kingdom of Yemen. In 1934, Yemen lost the northern province of Asir to Saudi Arabia.

Imam Yahya and his son and successor Imam Ahmad cut off Yemen from external influence for nearly fifty years. By abducting tribal sons as a short-term means of enforcing obedience, Imam Yahya alienated the tribes on whom his military rule was based. There were several revolts, but the imams always prevailed. In 1962, however, a republican revolt – aided by the Egyptian army and aggrieved tribes – drove out the fourth imam, al-Badr, to Saudi Arabia.

Imam al-Badr died in 1996 in Great Britain, to which he had emigrated on Saudi Arabia’s official recognition of the Yemen Arab Republic (YAR; commonly referred to as North Yemen before unification) in 1972. His eldest son, Ageel bin Muhammad al-Badr, who bears the title ‘King (Malik) of Yemen’, lives in exile in London.

Shiites

The Zaidi sect of Shiite Islam has long dominated Yemeni politics. Zaidism is a branch of mainstream Shiism that arose from a dispute over leadership concerning the fifth imam, in 740 CE. Zaidis are followers of Imam Zayd, whom they judged a more just leader than his brother Muhammad al-Baqir (the fifth imam of the Shiite mainstream ‘Twelvers’, who follow twelve imams, beginning with Imam Ali, the fourth ‘rightly guided’ caliph).

Zaidis are therefore also referred to as ‘Fivers’ (while Ismailis are called ‘Seveners’, from a dispute over the succession of the sixth imam). Compared to mainstream Twelver Shiism, Zaidi Islam is considered moderate. Its doctrine is similar to that of Shafii Sunnism. Theological disputes between Zaidis and Shafiis have seldom led to conflict.

Sunnis

The state religion of Yemen is Islam. Mainstream Islam – Sunnism – has predominated in the south and east since the advent of Islam, in the 7th century. Yemeni Sunnism follows the Shafii school of religious law, which is the second largest of the four existing schools of Sunni law. Throughout history, there has been little religious conflict between Shafii and Shiite Yemenis; in general, Yemenis are rather tolerant.

Since the 1970s, Saudi influence has been growing. Many Yemenis have worked in Saudi Arabia, some of them adopting puritanical Wahhabism, or Salafism, the predominant legal school of Sunnism there. Saudi Arabia has financed a large number of Wahhabi schools – called formally ‘scientific centres’ – in Yemen, where young people are educated according to Wahhabi beliefs. Wahhabi Salafism is not tolerant of Shiite Islam, denouncing it as a religion of kafirs (unbelievers).

A growing number of Yemenis now follow Wahhabi Islam. The movement is strong and appealing, as its followers are offered access to schooling, medical services, and business opportunities. Throughout Yemen, mosques are being converted to Wahhabism by the appointment of Wahhabi imams. If a tribal sheikh ‘converts’ to Wahhabism, the whole tribe is converted along with him. The Sunni proportion of the Yemeni population is consequently believed to have increased from half to more than three-quarters.

Ismailis

The Ismaili branch of Shiite Islam arrived in Yemen with the Fatimid Empire, which ruled from Egypt from the 8th until the 10th century. Ismailis (sometimes referred to as ‘Seveners’) originally differed from mainstream Shiism on the topic of the succession to the sixth Imam. However, they have since drifted towards a more liberal religious position, branching off into a number of sects.

Ismaili Islam has tended to spread eastwards, to India and parts of Iran, but enclaves can be found also in countries such as Turkey, Syria, and Yemen. Only 1-2 percent of Yemenis consider themselves Ismaili (Yemeni Ismailis call themselves Tayyibis). They are also known as al-Bohra (from a Gujarati word meaning ‘traders’; it is the designation for converts to Ismaili Islam outside Yemen). Al-Bohra is renowned merchants, who have their own market in the vicinity of Bab al-Yaman, the open-air market in Sanaa’s Old City.

Jews

Jewish children at school Photo HH[/caption]Judaism came to Yemen when Jews migrated from the region of Jerusalem after the last Jewish kingdom in Palestine was defeated by the Romans, in the first century CE. In fact, in pre-Islamic times, Judaism (sometimes with Christianity) dominated significant parts of Yemen, as local rulers converted. The most famous Jewish ruler was Yusuf Dhu Nuwas, a Himyari king who ruled from Zafar in the 6th century. Dhu Nuwas reportedly persecuted Christians in reaction to the persecution of Jews by the Byzantine emperor in the northern Middle East. The rule of Dhu Nuwas was ended by a large force of Christian Ethiopians.

Judaism and Jews remained in Yemen. After the arrival of Islam, Jews, who were, like Christians, ‘People of the Book’ – ahl al-kitab; Jews, Christians, and Muslims share many of the revelations of the Old Testament – were granted the status of dhimmis and were protected by Muslim rulers, although they did not enjoy full civil rights: Jews were not allowed to ride horses, wear colourful clothes, or build houses that were taller than Muslim buildings. Instead, they built cellars in which they could store, among other things, their wine, which they were allowed to drink. Orphaned Jews were often converted to Islam. In the 19th century, Jews were given the degrading task of cleaning public baths, toilets, and sewers.

At the beginning of the 20th century, there were some 80,000 Jews in Yemen, spread over 1,050 communities, predominantly in Zaidi areas. As many professions were forbidden to them, Jews in Yemen made a living as artisans and craftsmen: jewelers, weavers, silversmiths, shoemakers. This made first-class Muslim citizens very dependent on second-class Jewish citizens.

By the end of the 19th century, Jewish migration (Hebrew, aliyah) to Palestine began. At first, only a few families left, but when the State of Israel was founded, the interest of Yemeni Jews grew. In 1950, with the consent of the Yemeni imam, the government of Israel mounted Operation Magic Carpet, airlifting (by British and American planes) between 35,000 and 50,000 Jews from Aden to Israel. Many Yemeni Jews saw this as the fulfillment of God’s promise to end their suffering and diaspora, but they have found their reception in modern, secular Israel disappointing. There was little demand for their knowledge and skills, so Yemeni Jews became members of Israel’s lower social classes, along with black Ethiopian Jews.

The Yemeni Jewish migration has continued throughout the years. The remaining Jewish population lived largely in the north, but, as a result of the Houthi war, these last Jews were expelled from the city of Saada and its surroundings. In 2008, after a violent incident in Rayda in which a rabbi was shot in cold blood and his killer escaped prison, the majority of the large Jewish community in Rayda also left for Sanaa. From there, some went on to the United States or Israel.

Other Minorities

There is virtually no immigration into Yemen. Exceptions are the small expatriate communities in Sanaa and Aden and a growing group of Somali refugees who have crossed the Red Sea during the last decade in small boats owned by human traffickers, fleeing the dire conditions in southern Somalia. From 2006 onwards the number of boat refugees to Yemen has held at about 50,000 per year. The Somali refugees live in large refugee camps near Aden and Bir Ali, which are supported by the UNHCR, and on the outskirts of large cities, especially Sanaa and Aden. Most refugees try to continue their voyage to Saudi Arabia, one of the Gulf countries, or Europe, while some return to Somalia. Many remain in Yemen. In 2010, their number exceeded 200,000, as the influx and natural growth of the population continued.

Another exception to the rule of limited immigration is the Akhdam (literally, ‘servants’), descendants of immigrants of African origin. The Akhdam are believed to be the offspring of Christian Ethiopian warriors who invaded southern Arabia in the 6th century but who were later defeated and forced to serve the Yemeni Arab population. Some studies indicate that the Akhdam may also include indigenous Yemenis from the Tihama and more recent immigrants from the African side of the Red Sea.

The Akhdam, who prefer to be called muhammashin (literally, ‘marginalized ones’) number between 250,000 and 500,000, although estimates by Akhdam activists are much higher, up to three million. In practice, the Akhdam lack many civil rights, including the right to own land, to obtain building permits, or to hold passports. The Akhdam are not entitled to social services, and foreign aid generally passes them by. The Akhdam do not intermarry with Yemeni Arabs, and the Akhdam still perform the most menial jobs in Yemen.

Akhdam can be seen everywhere in Yemen, dressed in orange overalls, sweeping the streets. There are hardly any dustbins on the streets of Yemen, so there is always plenty of rubbish to be collected. Every building block in Sanaa has its own Akhdam to collect the refuse and sweep the streets. According to the local managing director of Sanaa’s waste-collection service, the Akhdam in official jobs are nowadays paid reasonable wages.