Market in Yemen ahead of the Eid al-Fitr / Photo Corbis

Market in Yemen ahead of the Eid al-Fitr / Photo Corbis

Introduction

The era of Yemeni domination of trade routes and much sought-after export products – such as frankincense, myrrh, and coffee – is long gone.

The Yemeni economy is impoverished, and virtually no products are produced for export. The economy rests largely on oil exports, remittances from abroad, and foreign aid, fueling a consumer market, the informal sector, and a booming qat production.

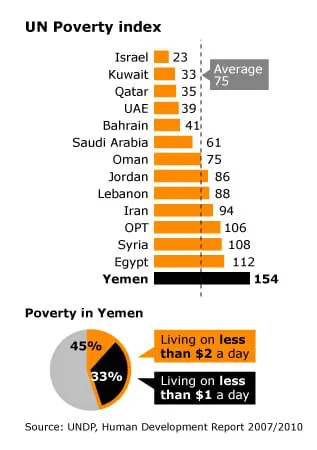

Yemen’s average annual per capita income stands at USD 2,213, well into the lower range of low-income countries. By comparison, the average income in Saudi Arabia is USD 23,274, and in Egypt USD 5,269: Yemen is the poorest country in the Middle East, and income is very unevenly distributed. Nearly 34.8 percent of the population has an income below the national poverty in 2009, and 17.5 percent below USD 1.25 per day in 2011.

There is widespread unemployment; up to 52.9 percent of the population was unemployed in 2008, up from 38 percent in 2001 (Human Development Report 2011). 23 percent of the labor force consists of children.

The ongoing conflict in Yemen has led to food insecurity for about 17 million Yemeni (60 percent of the population). This is in addition to the 7 million considered extremely food insecure.

Since the start of the conflict, more than 2.8 million people have been internally displaced, and 14 million cannot obtain basic health care.

The economy, which was already fragile, weakened further due to disruption to oil production and other economic activities. This saw gross domestic product (GDP) declined by 28 percent in 2015.

However, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) expects the situation to improve in 2017, with 12.6 percent in 2017, up from 4.2 percent the year before. Inflation in 2015 was 40 percent. This is also expected to improve, dropping to 18 percent in 2017.

GDP in 2015 was $37.73 billion, compared with $43.2 billion in 2014 and $40.1 billion in 2013. GDP per capita in 2015 was $1,334.

Yemen ranked at the bottom of the Global Competitiveness Report 2016-2017, coming in 138th.

The World Bank stepped in to provide help through the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) among the worsening economic conditions. By August 2016, the Yemeni Central Bank was no longer able to meet its credit commitments, except the International Development Association and the International Monetary Fund.

According to the World Bank, Yemen’s social and economic prospects rely on improving its political stability and security. The bank notes that Yemen will continue to depend on external aid and donor support to recover and rebuild confidence even after the war.

Urban Economy

After the revolution of 1962, Yemen’s economy opened up with few restrictions. In the 1970s and 1980s, every family had at least one male relative working in Saudi Arabia, who sent home large sums of money. Estimates put the number of Yemeni migrants working in the Gulf in the 1980s at up to 1.8 million (in 2011, Yemen had 24.8 million).

Yemen has had a consumer market ever since, which feeds a large informal economy, estimated to be 60-80 percent of the total economy. Street vendors are everywhere, and much of the trade goes unrecorded; the same is true of the large service sector. Construction is booming in Sanaa and Taizz, with laborers armed with tools waiting to be picked up at the main crossroads.

Yemenis are born traders. The streets of Yemen are lined with small shops offering the same stock, with little specialization. Open-air markets are common, with vendors selling just one product or small-scale artisan products on the pavements. Industrial production is virtually non-existent, apart from a biscuit factory in Taizz (and the Afif conglomerate, which produces mineral water and lemonade). Nearly everything in Yemen is imported.

The only encouraging exception is urban construction, which is booming as urbanization accelerates.

Infrastructure

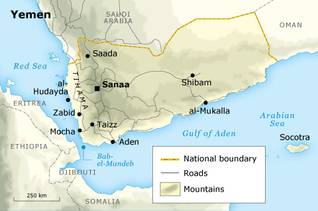

There are no railways in Yemen. Two-lane roads connect the cities and towns along the backbone of the mountain range and east and west of it. Many of the thousands of villages are accessible only by unpaved roads, which are often subject to landslides and deterioration, leaving many people cut off from medical and other basic services.

The large island of Socotra and several smaller islands, mainly in the Red Sea, are also part of Yemen. Most of the smaller islands are uninhabited and are used as military bases.

In 2007, plans were announced to build a bridge between Yemen and Djibouti. The bridge will connect the Middle East and Africa, which are, at present, connected only at the Sinai Peninsula but which were once united as part of the supercontinent of Gondwana and drifted apart about 30 million years ago. The bridge will span 3.5 kilometers from Yemen to the island of Perim and from there more than 20 kilometers across the Red Sea to Djibouti.

The first 5 kilometers will consist of approach bridges, and the middle span of 10 kilometers will be supported by three pylons towering more than 400 meters above the 300-meter-deep sea.

Heading the plan is the Dubai-based Middle East Development LLC, headed by Tarek bin Laden, a half-brother of Osama bin Laden. Engineers of the Danish company COWI draughted a preliminary design of the bridge and calculated that construction would take at least twelve years and USD 20 billion.

The proposed bridge between Africa and Arabia. Source: Fanack

The proposed bridge between Africa and Arabia. Source: Fanack

Part of the plan is the construction of a new city on either side of the bridge, involving another USD 180 billion. In June 2010 the Dubai-based Al Noor Investment Company announced a delay of phase 1 of the plan, caused by a delay in the signing of a framework by the governments of Yemen and Djibouti.

Oil and Gas

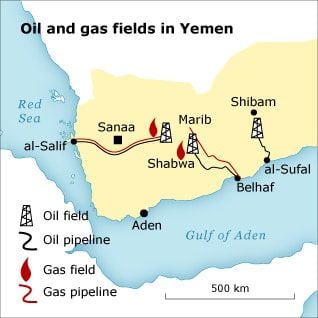

Petroleum was discovered in the eastern governorates during the 1980s and 1990s. Production is always franchised to foreign oil companies, but oil has brought the government an unprecedented income source.

This resulted in a stronger state capable of establishing basic social and medical institutions throughout the country. This, in turn, resulted in the challenging of tribal autonomy, as more people became dependent on income from national government programs in education, health, and social services. However, most oil revenue has benefited only a small group of already wealthy people within and surrounding the Saleh regime.

Unlike its neighboring countries, Yemen is not blessed with huge oilfields. Crude-oil production began in 1984, at 8,000 barrels a day, increased to over 438,000 barrels a day in 2004, and then decreased to 130,699 barrels in 2013, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. Saudi Arabia produces twenty times as much, and Oman twice as much.

In 2005, oil revenues accounted for 12.5 percent of the GDP, 67 percent of government income, and 86 percent of export revenues. In 2009 these figures rose to 30 percent, 70 percent, and 63 percent, respectively, underlining the absence of a significant economic structure in Yemen besides oil production.

While the oil sector revenues accounted for such a large part of the state’s income, oil production facilities have never developed to meet the requirements for efficient production. Oil production is decreasing continuously at such a rate that it will prevent the state from depending on high oil prices to compensate for the reduced production.

As calculated by the World Bank, oil production is already decreasing, and Yemen’s known oil reserves will run out in 2017. Still, the exploration of new fields is underway, not only in the eastern desert but also in the Arabian Sea and the Red Sea. Yemen and Total have discovered a large natural-gas field in the eastern lowlands. Production, under foreign management, began in 2009.

Exploration and production are largely in the hands of foreign companies under franchise from the Yemeni oil ministry. The companies American Hunt and Total are major producers in Yemen. They have been attacked by tribes – who want a larger share of the profits – at production sites and even in Sanaa’s capital.

Most of the oil produced is sold as crude oil, although some are refined in Aden. In al-Hudayda and at al-Salif, additional refineries are being built at the end of the pipeline that runs from the oilfields to the Red Sea.

Agriculture

Yemen is still a very rural country, with 68 percent (2010 figure) of the population living a self-sufficient, agricultural life in small mountain villages.

Around half the population still tills the earth to feed itself. The small amount of surplus produce is sold at the local market. Surplus agricultural value has risen to USD 511 per worker but is still meager, compared with USD 1,100 in Oman, USD 14,000 in Saudi Arabia, or USD 39,000 in the Netherlands.

In 2010, the agricultural sector contributed an estimated 8.3 percent to the gross domestic product (GDP). Most of this, however, is from qat production.

Food security is low. More and more land is being set aside for qat cultivation; food production has decreased to a third of the total demand. Moreover, in the 1980s, Yemen’s economy shifted to a consumer market fuelled by expatriates’ remittances in Saudi Arabia.

Many of the ancient, labor-intensive terraces that adorn the mountains were subsequently neglected, leading to erosion. Agriculture on a somewhat larger scale is practiced only in flat Tihama and in the vicinity of Marib.

The rebuilding of the dam in Marib has not led to a significant increase in food production, as a canal system has yet to be completed.

Coffee

Legend has it that coffee was first discovered in Ethiopia, but the global spread of coffee certainly began in Yemen.

Traders marketed Yemen-grown coffee throughout the Middle East from the 10th century onwards. Coffee became very popular after it was introduced in Istanbul in the 16th century, and it spread from there to the West.

In the 17th century, the Dutch East India Company attempted unsuccessfully to monopolize the trade by controlling Yemen’s southern port of Mocha. When that effort failed, they took seedlings to the Dutch East Indies, from where the rapidly increasing global coffee production spread.

Yemen’s mountains still produce coffee of exceptional quality (Harasi, Bani Matar, Ismaili). Still, the country produces only about 200,000 60-kilogram bags of green coffee beans per year, compared to one million bags in Kenya and over four million in Ethiopia.

Qat

Qat (khat) is both a drug and a social custom. Qat is a drug in the sense that it leads to an intermittent state of alert exhilaration. Qat is made from a shrub called Catha edulis. The twigs’ young leaves are chewed slowly and held in one cheek, and the drug is absorbed through the mouth.

Qat is always chewed in a group and usually with close friends. Intense social interactions and lively conversations and singing, and the reciting of poems are the results. Traditionally, the qat was used by the well-to-do and only on weekends or special events, but the use of qat has increased greatly since it has become more widely available.

Qat has become a dominant factor in Yemeni life. It dominates the economy, taking up half the available working hours and, in many cases, half of the household expenditure. Qat dominates daily life, as the whole country comes to a standstill after midday prayers, and people seek the company of friends to sit and chew together. Qat consumes half the country’s water supply.

The increase in qat use has many negative effects, from individual health problems to the paralysis of the Yemeni economy. Voices call for limits on the use of qat, but there is little public support for such restrictions, and no concrete policies have been developed (although some efforts have been made).

More and more agricultural land is being planted with qat shrubs, displacing food crops such as sorghum, maize, tomatoes, and potatoes. In the 2010s, qat takes up 11 percent of agricultural land, twenty times as much as in 1970. Qat shrubs consumed large amounts of water and were traditionally confined to the rain-fed mountain terraces on the mountains’ wetter (western) side.

As more diesel pumps have been installed and groundwater and fossil water (old groundwater that is geologically sealed off from replenishment) have become widely available, qat is now cultivated throughout Yemen.

The reason for the abundance of qat shrubs is that qat is a cash crop; its value is fully half the value of all cash crops. It yields far more profit than other crops, accounting for an estimated 25 percent of GDP. Qat production and trade provide rural households with important additional income and employ an estimated 20 percent of the working population. As qat is produced outside the formal economy, reliable figures are hard to come by and should be seen as only rough estimates.

In 2005 qat production reached 124,000 tons, up from 8,000 in 1970. Studies show that over 70 percent of households use qat and that qat consumption accounts for a quarter of average household expenditure; for poor people, this percentage is much higher, often cutting into food and other basic needs. Ironically, chewing qat allays hunger.

According to Yemen’s five-year plan published in 2005, 20 million working hours are wasted daily on qat consumption. While prices of all commodities at least quadrupled due to shortages during the 2011 Arab Spring, qat prices and availability were unaffected.

Methods of qat cultivation have improved, and better varieties have become available through selection. As a result, qat can now be harvested up to six times a year, compared to twice a year in the past. The intensive cultivation consumes large amounts of costly water, and pumps are taking an increasing share of the profits.

It is estimated that qat production uses as much as 80 percent of all irrigation water and 40 percent of all the water used in Yemen. As rainfall does not refill groundwater reservoirs at the same rate as it is pumped out of the ground, water is rapidly becoming scarce.

Many reservoirs have already dried up, making it necessary to drill deeper and deeper or search for new fossil-water fields. The government is trying to limit the number of pumps and the wells’ depth, but corruption, tribalism, and nepotism often stand in the way.

The groundwater reservoir beneath Saada has already dried up, and the Sanaa reservoir will be exhausted in ten to fifteen years. This has prompted the government to plan to relocate nearly the entire population of Sanaa to a new city on the Red Sea coast, where water produced by desalination will be available. In Taizz and elsewhere, the search for new aquifers continues.

Whereas traditional qat production used no fertilizers or pesticides, today’s intensive cultivation requires large amounts of chemicals. According to a recent study, qat production consumes 80 percent of all pesticides used in Yemen. The result is degradation and contamination of the soil and surface groundwater.

Worse still, because the chemicals contaminate the plants themselves, qat use presently involves much higher contamination levels. As a result, tongue and mouth cancers are becoming major diseases in Yemen. Due to improper use or the use of outdated chemicals that have been banned elsewhere, the levels of contamination are sometimes so high that sudden death of qat users may occur.

A recent study revealed that 80 percent of all men using qat experience sexual impotence.

Fishery

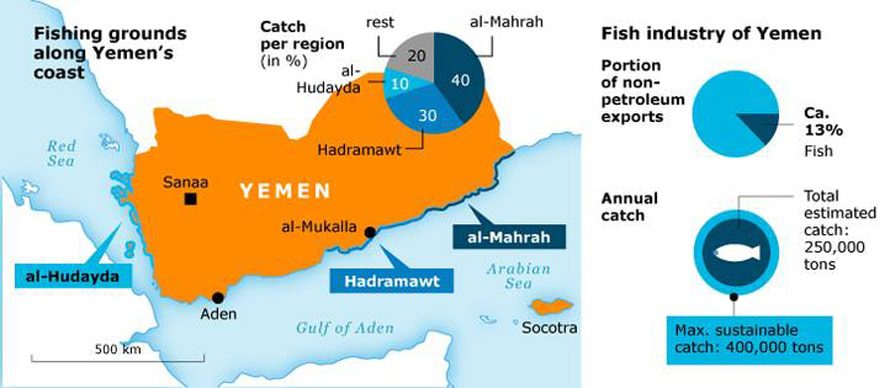

There is an abundance of marine wealth along Yemen’s long coasts and around its islands. Marine biologists consider the Arabian Sea to be a highly productive fishing ground, and the Red Sea is considered moderately productive.

The Yemeni fishing industry is not yet very sophisticated or organized, three-quarters of the fish production being caught by small boats and sold locally or regionally.

The governorate of al-Mahra (in the east, bordering Oman) catches 40 percent of the total estimated catch of 250,000 tons of fish.

The governorates of Hadramawt (30 percent) and al-Hudayda (on the Red Sea, 10 percent) come in second and third. It is believed an annual maximum catch of 400,000 tons is sustainable for Yemeni waters.

According to Yemen, fishing accounts for a modest (1 percent) share of GDP. Still, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) estimates 15 percent, probably because it includes locally-sold production.

There are approximately 70,000 fishermen in Yemen, while the total workforce dependent on fish production is estimated at over 200,000. Revenue from fishing exports accounts for 13 percent of all non-petroleum exports.

Yemen regards the fishing industry as a very promising sector. The growth of fish production was significant (15 percent) during the period 2000-2005 but has apparently shrunk to below the annual target of 7 percent.

Tourism

Tourism has a large economic potential but remains on a small scale. The poor tourism infrastructure – there are not enough adequate hotel beds and restaurant seats for tourists – inhibits growth.

In 2005, tourist arrivals topped 300,000 – up from 100,000 in the previous decades – half of those from Arab countries. That year, tourist expenditures amounted to 2.4 percent of GDP, or 33 percent of total export value, and provided jobs to some 34,000 people.

In 2009, 438,000 tourists visited Yemen, 68 percent of whom came from Arab countries. In comparison, Yemen’s neighbor Oman, which has many fewer antiquities, attracts up to a million tourists a year, while Egypt welcomes over a million tourists a month.

Yemen’s image in the international media, too, discourages tourism. The kidnappings of the 1990s did not materially affect the number of tourists coming to Yemen. Still, the tourist killings, presumably by al-Qaeda affiliates, did far more harm in 1998 and again in 2007 and 2008.

A significant part of Yemen – the warring north and the tribal east – has been unsafe and off-limits for tourists since 2004. Foreign governments frequently issue travel warnings to potential visitors.

The economic potential of tourism, however, is enormous. Together with well-restored ancient cities, the unrivaled architecture of Yemen could make Yemen a prime tourist destination. There is a wealth of archaeological monuments and many remains to be discovered or restored.

The scenic mountains offer ample year-round opportunities for active tourists, as do the long (albeit very humid) coastline and small islands.

Workforce and Labour Migration

Almost a million Yemeni migrant workers were expelled from Saudi Arabia after Yemen declared its neutrality during the 1990-1991 Gulf War; it is said that at least one male member of every Yemeni family was working in Saudi Arabia during the 1970s and 1980s. Many have since returned. The 2004 census showed that 1.2 million Yemenis still live in Saudi Arabia, predominantly in Riyadh. Another 500,000 reside elsewhere globally, with large communities in Manchester, in the UK, and Detroit, in the US.

Saudi Arabia has built a wall along part of its border with Yemen to stop the smuggling of commodities, arms, and people. This nearly led to an armed conflict with Yemen in 2004 and discord with the tribe that occupies the land on both sides of the wall. It is unclear how much of the barrier has been completed.

Foreign Aid

In the 1970s and 1980s, as many as a million Yemeni migrants worked in Saudi Arabia, contributing financially to Yemen’s booming consumer economy. Still, most of them were expelled due to Yemen’s neutrality in the 1990-1991 Gulf War. Many have since returned to work in Saudi Arabia.

The total contribution of remittances to the Yemeni GDP stood at 16 percent in 2000 and 7 percent in 2007.

Foreign aid has for many years been an important contributor to the national economy and social services, but it has dwindled to USD 12 per capita or about 3 percent of GDP. Debt service currently stands at a third of the Yemeni national income.

Economists blame the absence of real industrial development on the relatively high labor cost and low profits in the 1980s. Much of the remittances did, however, trickle down to the middle and lower-income groups, feeding the informal economy and giving many the hope of a better life.

This stands in stark contrast to oil revenues since the 1990s, which have not trickled down. Yemen has been increasingly dependent on foreign donors ever since.

The Yemeni government worked hard to encourage foreign investment in Yemen. Foreign investors and the World Bank continue to push the government to promote good, transparent governance, eradicate corruption and nepotism, and improve the inadequate and unsafe infrastructure. In 2006 investors seemed very reluctant to invest in Yemen, total foreign investment amounting to a mere USD 144 million.

Donor conferences in The Hague in 1995 and London in 2006 and 2010 yielded large promises of support, amounting to over 5 billion USD. Still, the World Bank concluded in 2010 that Yemen had received only 10 percent of the 2006 package, as it did not meet demands for political and economic restructuring and transparency.

Structural adjustment programs have been approved repeatedly by the International Monetary Fund and World Bank but have never been properly implemented or successful.

Harsh reforms, such as cutting subsidies for food and oil and laying off many civil servants, were imposed, but reforms affecting the upper class were never enforced.

This has resulted in an ever-growing gap between poor and rich, visible in contrast between luxurious neighborhoods in certain parts of Sanaa and the growing number of beggars. In 2010, 45 percent of the population lived on less than USD 2 a day, up from 39 percent in 2007.

Economic Challenges

President Abd Rabbuh Mansur Hadi succinctly described the difficult Yemeni situation: “75 percent of Yemen’s problems are related to the economic situation”.

Pressing problems

The World Bank estimates that the number of citizens living below the poverty level in 2014 was 45.7 percent, compared with 42 percent three years earlier. Currently, there is no apparent middle class, and half of Yemen’s children suffer from malnutrition. Despite the progress that the country has achieved in some areas—for instance, the decrease in infant mortality—it is unlikely that Yemen will reach the United Nations Millennium Development Goals.

Yemen’s formal labor force is small. As there is no central system for recording and analyzing data, figures regarding the Yemeni economy are unreliable. In 2005, a Ministry of Public Works and Highways consultant estimated the potential labor force at five million, of whom one million are unemployed. These figures seem reasonable. In 2010, the United Nations Human Development Report (HDR) put the number of unemployed Yemenis (15-64 years) at 40 percent.

Conservative estimates are that Yemen’s unemployment rate has reached 35 percent—and more than 55 percent among the younger generation. In 2013, Saudi Arabia’s increased restrictions on labor migrants increased Yemen’s unemployment levels; approximately 300,000 to 400,000 illegal Yemeni workers returned to Yemen. This is a worrying picture, given the demographics of Yemen. The high population growth rate will increase pressures on economic, educational, and health services.

Given that half the population is aged under fifteen, about 700,000 young people theoretically enter the labor market annually. Most Yemenis, however, still work their own land (52 percent, in 2006) or are partially (self-)employed in the informal sector. Of all Yemeni women, 60 percent work unpaid, mostly on their own lands.

During the first decade of the 21st century, Yemen’s economy depended on the oil and gas sectors. Between 2010 and 2012, the proceeds from these constituted 60 percent of total government revenues. Oil and gas revenues helped former President Ali Abdullah Saleh provide fuel subsidies, which are currently difficult to maintain economically. While the oil sector revenues contributed more than 70 percent of the state’s income, oil production facilities have never developed to meet the requirements for efficient production. Oil production is decreasing continuously at such a rate that it will prevent the state from depending on high oil prices to compensate for the reduced production.

Yemen possesses natural gas reserves in the Marib governorate, near Sanaa, which is transported through a 320-kilometer pipeline to the natural gas liquefaction plant on the Belhaf region southern coast liquefied natural gas is shipped to Asian, American, and European markets. However, the revenues from natural gas exports will be insufficient to cover the deficits resulting from the decrease in oil production. Furthermore, much of the energy-sector infrastructure is continuously targeted by armed groups. Sabotage has resulted in the disabling of liquefied gas exports in 2012.

It is expected that natural gas will be used for power production, which is also highly dependent on the oil sector in Yemen. Sabotage and the shortage of energy in Yemen are perennial problems.

Some analysts see the depletion of water resources as a more pressing problem than reducing Yemen’s oil reserves. Helen Lackner, an expert in Yemen affairs and a specialist in rural development and water management, states that 70 percent of Yemen’s inhabitants live in rural areas and that only 47 percent have access to potable water. And the situation is worsening due to the climatic change, including waves of extreme drought and heavy rains in some regions. Every year, Yemenis die as a result of conflicts over control of areas with water resources. Within a few years, Sanaa might be the first world capital to witness its water resources’ disappearance.

The elites’ control of the economy, including communication and manufacturing, is a prominent feature of the Yemeni economy. This phenomenon does not seem to have abated with the departure of former president Ali Abdullah Saleh from his post or the new government’s seating.

In the absence of investment opportunities and security and political stability, the state is facing a loss of well qualified Yemeni professionals, the so-called brain drain.

Latest Articles

Below are the latest articles by acclaimed journalists and academics concerning the topic ‘Economy’ and ‘Yemen’. These articles are posted in this country file or elsewhere on our website: