All forms of human trafficking and illegal immigration are a cause of concern for Sudan, both internally and externally, as well as a stumbling block in Sudan’s already tense regional and international relations. As a result, Sudan in 2018 is coming under serious pressure to cooperate with the European Union (EU) and the international community to decrease the pace of immigration to Europe from across Sudanese territories.

Millions Getting Ready

Many countries suffer because of immigration problems one way or another, but the Sudanese suffering is a three-dimensional one. Sudan is a major source of both legal and illegal immigrants from various origins as well as a destination for immigrants coming from neighbouring and remote countries who are fleeing conditions that are worse than those of Sudan. Hundreds of thousands of foreigners use Sudan as a transit point to other countries on their way to a promised paradise in Europe.

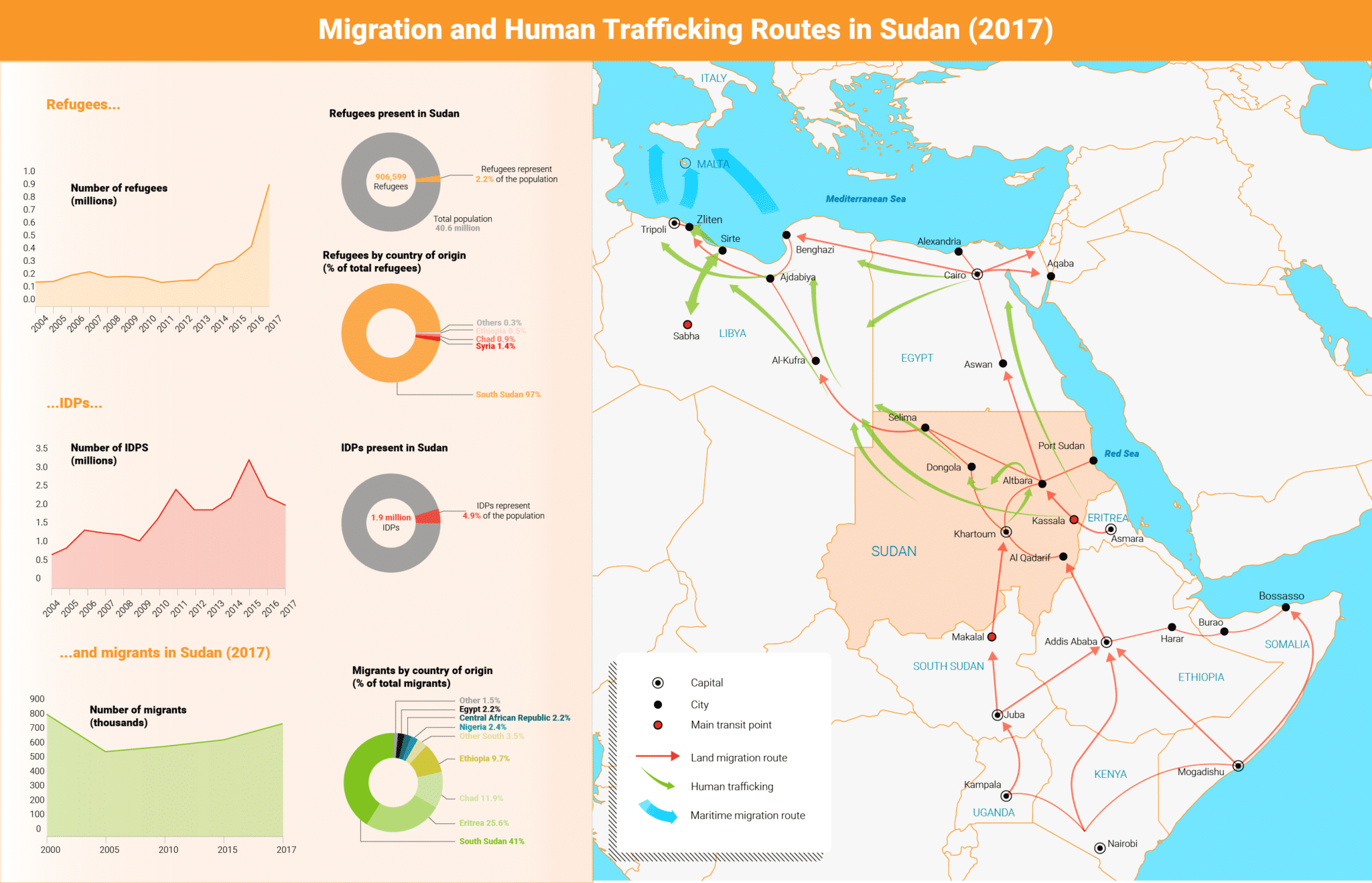

Nearly three million people in Sudan are at risk of human trafficking and illegal immigrations. Foreign refugees, especially from South Sudan and Eritrea, account for 900,000 of the immigrants, while the number of Sudanese internally displaced because of security and civil unrest is estimated at 2.2 million. Sudan ranks second among the countries hosting foreign refugees after Uganda in addition to ranking second in terms of the number of internally displaced persons, according to United Nations High Commissioner for refugees (UNHCR).

This is also in addition to hundreds of thousands of Sudanese youths from areas in northern and central Sudan that are stable but who see no prospects in these areas because of deteriorating economic conditions, high unemployment rates, terrible inflation rates, low local currency values and marginalization due to war, violence, social exclusion and various forms of discrimination. They constitute an army of people who dream of immigrating to Europe in search of a better life.

Because of its 6,700-kilometer difficult-to-control borders with seven countries, Sudan is an open international gateway for victims of human trafficking and others pursuing the European dream who come from neighbouring African countries, especially Eritrean youths fleeing long-term military service and Ethiopians fleeing poverty. Sudanese citizens belonging to tribes from both Sudan and Eritrea are involved in human smuggling across the eastern border of Sudan, particularly the tribes of al-Rashayidah and Bani Amir.

Smuggling or Trafficking?

All illegal immigration operations involve intermediaries seeking direct financial benefits, but researchers and international organizations interested in migration issues distinguish between two types – human smuggling and human trafficking – in terms of the relationship between smugglers and their clients or victims. A smuggler’s relationship with clients is based on mutual agreement while the relationship between human traffickers and their victims is governed by fraud, exploitation and abuse. The smuggler’s relationship with his clients ends with the termination of the contract and the immigrant reaching his or her goal, while human traffickers continue to deal with their victims for a long time and subject them to horrific exploitation and abuse throughout. Smugglers make money by transferring, sheltering and facilitating the entry of illegal immigrants to another country and providing them with documents and other services. Human traffickers, on the other hand, acquire material gains by exploiting their victims: blackmailing them and their families and perhaps employing them in hard labour, prostitution, drugs and other illegal activities.

Human Smuggling Routes from Sudan

Smuggling Sudanese and foreign refugees across the northwestern border into Libya is the main and most important migration route. The Sudanese government‘s weak control of some areas of Darfur, the absence of a central state in Libya and the collapse of security and spread of militia rule in Libya since the fall of Muammar Qaddafi‘s regime in October 2011 have all contributed to the influx of thousands of African immigrants.

According to UN reports, the number of boat immigrants moving from Libya to Europe jumped from 15,000 in 2012 to about 180,000 in 2016 before falling by one-third in 2017. More than 3,000 immigrants per year have died in the ‘death boats of the Mediterranean Sea’ over the past five years.

Some of them start the journey from the capital, Khartoum, and the cities of northern Darfur through the Greater Sahara and they experience arduous trekking along rough paths, causing many of their deaths. These journeys are led by traffickers running their business from the same cities.

CNN report on the enslavement and sale of African immigrants, including Sudanese in Libya, shocked global public opinion. Sudanese newspapers published numerous reports of the kidnapping and detention of Sudanese hostages in Libya, whose families were asked to pay ransom money for their release. In August 2018, police arrested some of the kidnappers who received ransom in Khartoum.

The second route begins from Eritrean and Ethiopian refugee camps in eastern Sudan, where more than 100,000 refugees, mostly Eritreans, live; more than four times the number of Eritreans live in Sudan as a whole. This route crosses the Sudanese-Egyptian border along the Red Sea in rugged mountainous areas known only to the local residents and it ends in the Sinai Peninsula in Egypt. From there, attempts are made to cross into Israel, where 35,000 of them currently live. This route is used by most Eritrean asylum-seekers in Israel who enter Egypt legally and cross the border, putting themselves at risk of gunfire from Egyptian and Israeli border guards, who have killed many of them. Egyptian authorities were able to partially close this route in 2014 after Israel tightened its border security; the deteriorating security situation in Sinai has limited the number of incoming migrants as well.

Multiplied Pressure on Europe

With the surge of illegal immigration to Europe in 2013 as a result of collapsing stability in Libya and Syria, Europe has become aware of the pivotal role of Sudan as a springboard and transit point for refugees – especially the Eritreans, whose numbers in Europe increased from 14,000 in 2012 to 37,000 in 2014 and a similar number in 2015 before later falling, perhaps partially because of Sudanese measures.

Despite the security, political and economic problems caused by the influx of foreign refugees into Sudan and the practice of using Sudanese territory as a transit point into Libya and then to Europe, the Khartoum government has cleverly turned the refugees into a trump card used with Europe to receive financial assistance and end its international isolation.

The Sudanese government has used the EU’s desire to limit illegal immigration through Sudanese territory to improve Sudan’s political negotiating position with the Europeans. European positions toward Sudan gradually changed in the second decade of the millennium from boycotts, restrictions, repeated talk about human rights conditions and victims of war in Darfur to a stage of cooperation and understanding with the government of Sudan, especially on combating illegal immigration.

Such cooperation culminated in the visit of the EU Commissioner for International Cooperation Neven Mimica to Sudan in April 2016. Mimica announced that the EU would grant €100 million to Sudan in 2016 and 2017 to implement projects to improve economic conditions and health and education services in conflict-stricken areas hosting large numbers of refugees and displaced persons serving as starting points for immigration routes used by human traffickers and smugglers. The EU provided another €60 million to Sudan for the same purpose in October 2017 and another €61 million in 2018 to fight illegal immigration and climate change. Sudan is also benefiting from other European aid programs related to food security.

The Sudanese government demanded the European aid also include strengthening border security by supporting police stations and detention facilities, as well as providing Sudan with planes and transportation means to support efforts to fight human trafficking. The government made these demands during a visit made by representatives of six Western donor countries to Sudan in April 2018.

Anti-Trafficking Efforts

Sudan’s first anti-human-trafficking law was passed in 2014; that same year, Sudan hosted an international conference sponsored by the Organization of African unity (OAU), the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and the International Organization for Migration (IOM).

The Sudanese police and security services have been noticeably active following the conclusion of the agreement and ensuing European support. Sudanese authorities have provided evidence that they handed over to Italy an Eritrean citizen called Murid Madhani, believed to be the most dangerous human smuggler, in June 2016. However, subsequent press reports confirmed that Sudanese authorities had handed the Italians another person, not Madhani, and that the latter lives freely in Uganda. Sudanese and foreign media have also reported details about the foiling of dozens of human trafficking and smuggling operations over the past four years. The infamous Rapid Support Forces (RSF) units arrested illegal immigrants in the desert on their way to Libya, not only from Sudan and neighbouring countries but also from countries such as Niger, the Congo, the Comoros, Bangladesh and Syria. Some of these attempts involved bloody clashes with smugglers, leaving 19 people dead on both sides.

However, these efforts are marred by corruption in law enforcement agencies. Many cases of collusion between human smugglers and some law enforcement personnel in return for money were identified. Earlier US reports accused the Sudanese government of failing to prosecute its employees who are believed to be involved in facilitating human trafficking in exchange for money as well as failing to prosecute smugglers.

In September 2018, Lieutenant General Mohamed Hamdan (aka Hemeti), commander of the RSF, announced that his forces would stop pursuing human traffickers in the Sahara because the international community does not recognize or appreciate Sudanese efforts in this regard. This statement appears to be a way of demanding the RSF’s share of the recent European support. That said, the RSF may slow down some of its activities for some time to exert pressures, but it is unlikely that they would stop it altogether as it is part of a commitment made by the Sudanese government to the EU and international community; reneging on such a commitment would no doubt be met with disapproval, or worse, a halt in the financial assistance that Sudan so desperately needs.