Introduction

By the end of the 1960s, popular protests held the government responsible for many failings, such as corruption, mismanagement and debilitating social inequalities. The inability to distribute oil revenue fairly and evenly was central to this, a failure that many Libyans explained by pointing to the state’s economic dependency on foreign oil companies and its political subordination to western political power.

Many people, foreign and Libyan, expected a coup, but when it came it was from an unexpected source. Nasserist socialism and nationalism provided an attractive ideological alternative, and the Egyptian President Nasser had contacts with a group of quite senior officers.

However, the men who took over in September 1969 were all junior, although they too were deeply influenced by Nasser’s example and at first modelled their thinking on his.

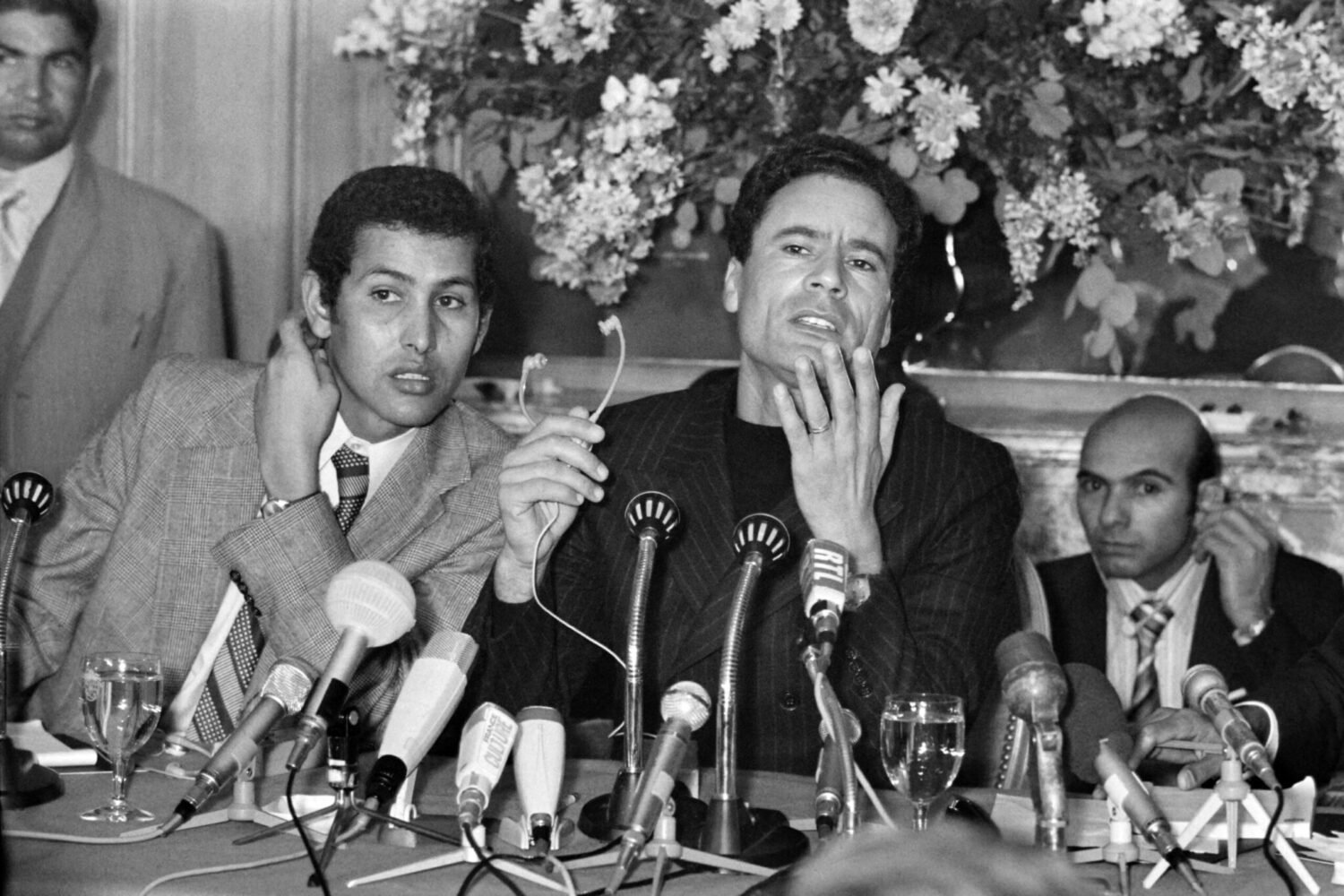

One of the officers who had been preparing a coup was Muammar Qaddafi.

Muammar Qaddafi (1942 – 2011)

Muammar Mohammed Abd al-Salam Abu Minyar Qaddafi, like most of the rebel officers, did not come from an elite background. He was reportedly born on 7 June 1942, in a tent in the desert near Sirte, among the Qadhadhfa tribe. His precise birthday is uncertain as his illiterate Bedouin family did not keep birth records. In 1952 he entered primary school at Sirte, moved to a preparatory (intermediate) school in Sebha in 1959, and, in 1961, entered secondary school in Misrata. In 1963 he joined the Military Academy in Benghazi.

Later, the bare bones of Qaddafi’s life were fleshed out with details that, in part, had propagandistic purposes. Authorized biographies emphasized three things: his desert background, the nationalist pedigree of his family, and his politicization at an early age. His family was poor. He was its first member to learn to read and write. While he was at primary school, he went home to his family only at weekends and slept in the mosque on weekdays. He was reportedly expelled for political activities from his preparatory school in Sebha and at secondary school in Sirte he organized a demonstration against Syria to protest the end of the union with Egypt.

Some of his school friendships lasted all his life. A number of Revolutionary Command Council (RCC) members that ran Libya immediately after the coup of 1 September 1969 knew each other from school. In Sebha, Qaddafi met Mustafa al-Kharroubi, later head of military intelligence, and Abdessalam Jalloud, for long his closest friend who became the first deputy chairman of the RCC and later Finance Minister.

Another Sebha friend was Mohammed al-Zway, who later became the last secretary-general of Libya’s General People’s Congress and thus the theoretical head of state from 2010 until 2011. At secondary school in Misrata, Qaddafi met Umar al-Meheishi, a future member of the RCC, which eventually led an attempted coup. But most of the future RCC members met Qaddafi in the Military Academy in Benghazi. One was Abu Bakr Younis Jabr, effectively the head of the army from 1970 until the civil war of 2011. And finally Khuwayldi al-Hamidi, long-term chief of police, whose daughter married Qaddafi’s son Saadi.

The ‘People’s Revolution’ (1969 – 1977)

On 1 September 1969 twelve junior army officers seized power. Because the bloodless coup took place on the first or ‘opening’ (al-infitah) day of September, it came to be known as the al-Fatih Revolution. The officers strongly identified with Nasserist Egypt, and used its terminology. Their organisation was the “Free Officers’ Movement” and they set up a Revolutionary Command Council (RCC), to rule the country. Although none of the names of its members were announced until January 1970, it was clear that Captain Muammar Qaddafi was its leader: he was promoted to colonel the day after the coup. Like Qaddafi, most members of the RCC had non-elite backgrounds, often from less prestigious tribes in the Sirte region.

Within a month, the RCC appointed a civilian-dominated government, but the RCC had final authority. In reality, this meant the authority of Qaddafi. To mobilise mass support, in 1971 he set up an Arab Socialist Union (ASU), also modelled on Nasserist Egypt. All other parties were banned, along with trade unions. The ASU was not popular and could not gather support for the regime’s revolutionary edicts.

Libyan nationalism was rather nebulous, and often defined in terms of past resistance to colonialism. At the same time, the RCC, like Nasser, talked of Arab nationalism. Policies concentrated on expelling the Western bases, reorganizing relations with the oil companies, and shifting power from the old bureaucracy. They nationalised banks, hospitals, and trading and insurance companies. Enmity for Israel led to the expulsion of the remaining Jewish population. But the new regime went much further than Nasser. Society was completely Arabised – only Arabic signs were allowed in the streets.

Qaddafi positioned himself as a much more personally devout Muslim than Nasser, and the regime went on to ban symbols of ‘Western moral decay’, such as alcohol, prostitution, pornography, casinos, and nightclubs. But he soon ran into opposition from mainstream Islamic scholars over such questions as restricting private property and the socialisation of the economy. He justified his policies by referring to a right to personal ijtihad (the interpretation of matters of faith), traditionally reserved to scholars.

The first attempted coup against the Qaddafi regime came in December 1969. The perpetrators, none of them members of the RCC, were crushed, but there were dissenters among the RCC too. In 1972 and 1973 two members resigned. In 1975 Umar al-Meheishi led another attempted coup and fled into exile, with three other RCC officers. These coups and the religious opposition showed that Qaddafi needed wider support than the Free Officers’ Movement and the RCC.

The Green Book

On 15 April 1973 Qaddafi gave a famous speech in Zuwara, after a much-publicized period of reflection in the desert. He outlined a new political system that replaced the Egyptian model with a plan for a “People’s Revolution.” He recast state structures according to a new Third Universal Theory, neither capitalist nor communist, that mixed socialist and Islamic theories.

After 1975 the RCC lost importance, but it remained formally in existence with its five surviving members (Qaddafi, Jaber, Kharroubi, Jalloud and Hamidi). Qaddafi began developing a new government structure which he outlined in the three short volumes of The Green Book. They prescribed a rigorous reform of Libyan political and economic structures: an apparent stateless society in which existing hierarchies were removed and the entire population was mobilised to manage affairs.

Green, a symbol of Islam, was adopted as the national colour of Libya. The main square on the seafront in Tripoli, which had been called the “Piazza Italia” in the colonial period and “Independence Square” under the royal regime, was now renamed “Green Square.” In 1977 the national flag was changed to a plain green field with no insignia.

The three volumes of the Green Book outlined the theory of a populist political structure. The revolution from below would create people’s committees in state institutions, local governments, businesses, schools, and universities each supposedly controlled by the workforce, a participatory rather than a representative democracy. This was the subject of the first volume entitled The solution to the problem of democracy: The authority of the people.

Direct democracy would replace traditional structures such as Parliament, political parties, and referenda. Parliament was said to be a form of dictatorship in which representatives removed power from the people by speaking on their behalf, rather than allowing them to speak for themselves. Political parties were believed to enable this alienation of the population from power, so they were to be abolished.

‘True democracy exists only through the participation of the people, not through the activities of their representatives’, was one of his assertions.

The second volume The solution to the economic problem: socialism dealt with economics (‘Profit is stealing’, ‘Partners, not wage labourers’).

The third volume The social basis of the Third Universal Theory dealt with cultural questions such as male and female relationships, family matters and sports, for example: (‘Sport must be practised by all and should not be left to anyone else to practise on their behalf’ – seemingly a prohibition of team sports).

An enormous cult was fabricated around these volumes. Pupils in school had to learn the book by heart. There were editions in 84 languages, including Hebrew. It was the Green Book Studies Centre’s task to distribute and promote the work and they were handed to international visitors.

The theory in The Green Book resulted in what one of the omnipresent populist slogans called for: “Committees Everywhere.” Local people’s committees and congresses, trade unions, and professional organizations sent delegates to higher congresses and popular committees. They sent delegates to a national General People’s Congress (GPC, essentially a parliament) of about 1,000 members. These delegates chose the secretaries (equivalent to ministers) of the GPC, which acted as a cabinet. The GPC chair was a general secretary, roughly equivalent to a Prime Minister. This allowed Qaddafi to replace existing cadres with new leaders from lower social classes and to remove opposition elements (Communists, Ba’athists, and the Muslim Brotherhood).

The theoretical flaw was that Qaddafi never explained how delegation differed in practice from the system of representation it supposedly replaced. And sensitive issues such as defence, oil, and foreign policy were excluded from the committees’ control.

The Jamahiriya

In March 1977 Qaddafi abolished the RCC and announced the “Era of the Masses.” Libya became the Jamahiriya, “the State of the Masses.” In April he purged the armed forces. In 1980 Qaddafi took his economic propositions to their logical conclusion by ending private commercial and retail transactions, distribution and landholding. He demonetised the currency and replaced it with new notes, and replaced private shops with huge state supermarkets.

Although Qaddafi encouraged the population to manage affairs, Qaddafi’s populism was not popular among the people. Also, the new system quickly produced either apathy or decisions of which Qaddafi disapproved. To avoid these problems, Qaddafi set up parallel structures to ensure that things were done, and in the way he wanted.

One of these parallel systems was the Forum of the Companions of Qaddafi, a group of supporters, mainly former school friends and teachers of Qaddafi, which served as a reservoir of personnel to staff civilian posts (such as diplomats, administrators, and university professors).

Another was the system of Revolutionary Committees, a line of authority Qaddafi set up in 1977, separated from the political authority of the people. They consisted of enthusiasts of Qaddafi’s revolutionary policies who provided coercive force to ensure that they were implemented and that popular committees followed the official line. While they were supposed to stimulate political awareness, they soon went much further and replaced the regular system of authority: revolutionary courts replaced the existing legal system. They were particularly active in policing the universities.

In March 1979 Qaddafi and the remaining members of the RCC publicly withdrew from the GPC, leaving it to manage affairs. With the revolutionary committees in place to develop and maintain doctrine, Qaddafi now had no formal state position. He called himself the ‘Leader of the Revolution’ or ‘Brother Leader’.

All this left little space for public political expression, so alternative views found an outlet in mosques and religious activity.