An Iraqi nuclear program got off the ground under Saddam Hussein during the 1970s. Well financed and well organized, its pièce de résistance consisted of a French-provided reactor (Osiraq) that was planned to be built not far from Baghdad.

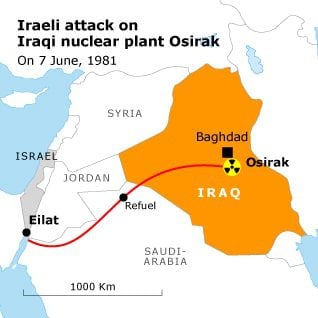

However, there were repeated delays, some of them probably due to sabotage carried out by Israel’s intelligence service Mossad. In the summer of 1981, just before the reactor was finally due to go critical and produce plutonium, it was destroyed by an attack mounted by the Israeli Air Force.

Since the core containing uranium had not yet been installed, and since the raid was carried out during the Muslim weekend, there was no radioactivity and no loss of human life.

The Iraqi nuclear program dates back to the 1970s. The means by which Iraq tried to obtain nuclear weapons were diverse. In 1976, France sold Iraq a 40 megawatt test reactor called the Tammuz-1 reactor, or Osirak. The reactor was designed to run on highly enriched, weapons-grade uranium fuel, but this did not ring any alarm bells in Paris since the important ally had ratified the Non-Proliferation Treaty in 1969.

The Iraqi regime had counted on the ability to evade the watchful eyes of the inspectors of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), the United Nations nuclear watchdog. Through separation technology acquired on the black market Iraq planned to produce weapons-grade plutonium, five to seven kilograms a year. The yield did not just depend on the reactor, but also on the frequency of visits by French technicians and IAEA inspectors.

The Nuclear Program

In June 1981, just before the Osirak reactor became ‘hot’, an Israeli air attack destroyed the facility. The bombardment set the nuclear program back years. But it did not finish it off. Indeed, the attack galvanized Saddam Hussein to triple his efforts to acquire a bomb. He decided to replace the Tammuz-1 reactor or to develop a heavy water or enriched uranium reactor and associated plutonium separation capability; and, secondly, to develop a uranium enrichment production capacity.

All these efforts were moved further underground and out of sight of the IAEA – and of all spooks, for that matter. Iraqi scientists concluded, in 1981, that electromagnetic isotope separation (EMIS), the method used by the United States to produce highly enriched uranium for the Manhattan Project, was the most promising and that gaseous diffusion was second best. Gaseous diffusion was planned to produce lowly enriched uranium with which to feed EMIS that could produce highly enriched uranium. Centrifuge technology was seen as too difficult to buy or too complex to develop.

According to the online think tank Globalsecurity.org, the program to build a small arsenal was broad and well-funded. In 1988 it comprised:

1) Indigenous production and overt and covert procurement of natural uranium compounds, and industrial-scale facilities for the production of pure uranium compounds suitable for fuel fabrication or isotopic enrichment.

2) Research and development of the full range of enrichment technologies culminating in the industrial-scale exploitation of EMIS and substantial progress towards similar exploitation of gas centrifuge enrichment technology.

3) Design and feasibility studies for an indigenous plutonium production reactor, although there are no indications that Iraq’s plans for an indigenous plutonium production reactor proceeded beyond a feasibility study.

4) Research and development of irradiated fuel reprocessing technology.

5) Research and development of weaponization capabilities for implosion-based nuclear weapons at the A1 Atheer nuclear weapons development and production plant.

6) A crash program aimed at diverting safeguarded research reactor fuel and recovering the HEU for use in a nuclear weapon.

Ambitious as it was, the program encountered a lot of obstacles, some apparently insurmountable, in order to produce a working device. However, the country’s nuclear scientists had been able to buy the instruments necessary for the weaponization of the enriched uranium on the black market.

Ambitious as it was, the program encountered a lot of obstacles, some apparently insurmountable, in order to produce a working device. However, the country’s nuclear scientists had been able to buy the instruments necessary for the weaponization of the enriched uranium on the black market.

The Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein even publicly showed some special krytron switches used to detonate the conventional explosives used in the bomb design. When Iraq invaded Kuwait in 1990, it could not rely on a nuclear bomb as a strong deterrent.

Chances of obtaining such a bomb slimmed rapidly. The international community sealed the country off. In the summer of 1990 Iraq therefore embarked on a crash program to build a bomb from chemically isolate enriched uranium, from used and unused fuel of a Russian research reactor in Iraq.

The reactor fell under the aegis of the IAEA regime, but inspectors were not allowed in. Before the enrichment was completed – according to the Iraqi scientists it would have taken until 1992 – the bombing campaign started.

Facilities were hit and after the cease-fire inspectors from the United Nations Special Commission (UNSCOM) entered the country. Only then did the scope of the Iraqi nuclear program become clear.