While oil production activities have decreased dramatically due to the fighting, some level of production has been maintained in Syria and Iraq.

This production is split between the various groups controlling pieces of Syria. The prominent armed groups are the predominantly Syrian al-Qaeda-affiliated al-Nusra Front, the transnational Muslim extremist organization Islamic State (IS) (or ISIS, formerly al-Qaeda in Iraq), the moderate rebels, the YPG (Syrian Kurds) and the Assad regime.

For some, the rebellion is against al-Assad’s political repression whereas for others the turmoil has presented the opportunity to create a territory ruled by militant Islamic law. IS, which was born from the struggle against American occupation of Iraq after 2003 and has found fertile ground in a fragmenting Syria, is the main proponent of the latter.

As such, IS-controlled parts of Syria have become a magnet for radicalized Muslims around the world who wish to live in a proto-state governed according to extremist interpretations of Islam.

The violence stemming from IS constitutes a tangible threat to non-Muslims and Muslims adhering to other interpretations of Islam in Syria itself, in neighbouring territories such as Iraq (e.g. Yazidi and Christians) and further afield, including Western capitals, as has been communicated by the group’s leadership.

The expansionist and hyper-violent modes of behaviour displayed by IS have prompted detailed reviews of its ability to fund itself and raised concerns about the fate of Syria’s oil production.

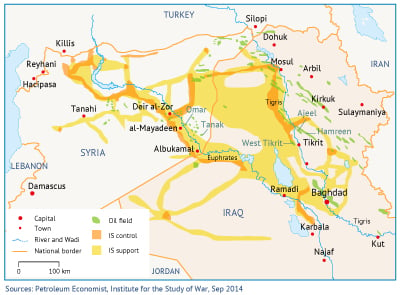

Most of Syria’s oil reserves are located in the east, near the border with Iraq and along the Euphrates River, with a number of smaller fields in the centre of the country.

According to news reports in late 2013, the Syrian government has lost control of nearly all of the country’s major oilfields. Syrian Kurdistan (in yellow above) contains roughly 60% of Syria’s oil reserves. The remainder is controlled by IS.

Maplecroft, the risk management firm, estimates that IS now controls six out of ten of Syria’s major oilfields (and at least four fields in Iraq). Revenue streams associated with newly controlled production are aided by the long-standing networks of black-market oil sales in the Levant.

Figures from the EIA estimate IS oil production at 30,000bbl/d in Syria, implying earnings of $1.2 million per day when sold at the black-market price of $40 per barrel (price in November 2014). If Iraqi production controlled by IS is incorporated, this revenue stream rises to an estimated $3.2 million per day.

Deliveries are mainly to local buyers and to export markets in Turkey. Most deliveries travel by truck and are sold at a steep discount.

Furthermore, it is important to note that there are long-standing grey markets in the region such that a local buyer of several truckloads may even sell to markets controlled by the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG). Reports state, however, that primary buyers are located just across the border in Turkey.

There are currently coordinated efforts underway to check the flow of black-market oil from Syria and Iraq, although the historical bootlegging in the region has made this difficult.

In April 2013, the EU agreed to allow oil imports from Syria, although only from moderate opposition groups, which do not currently have access to Syria’s oil export infrastructure. Gas has been of secondary interest given it non-exportability under the current conditions.

As foreign jihadist fighters have moved into Syria, many civilians have fled across its borders. Indeed, Syria has overtaken war-torn Afghanistan as the world’s biggest source of refugees, putting economic strain on its refugee-receiving neighbours.

However, it is the non-refugee movements (militants, jihadists) into neighbouring countries that constitute a serious security threat. For Iraq, this concerns its oil and gas infrastructure, whereas Turkey’s main consideration is the important pipeline system linking eastern supply sources with European markets.