Introduction

Iraq, along with Iran, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Qatar and the UAE, sits atop the world’s most prolific collection of hydrocarbon deposits, containing some 60% of the world’s known reserves. Yet, as Iraq has had the misfortune of its borders crossing a large share of these reserves, those borders have been the locus of the instability that has stifled development for more than 30 years.

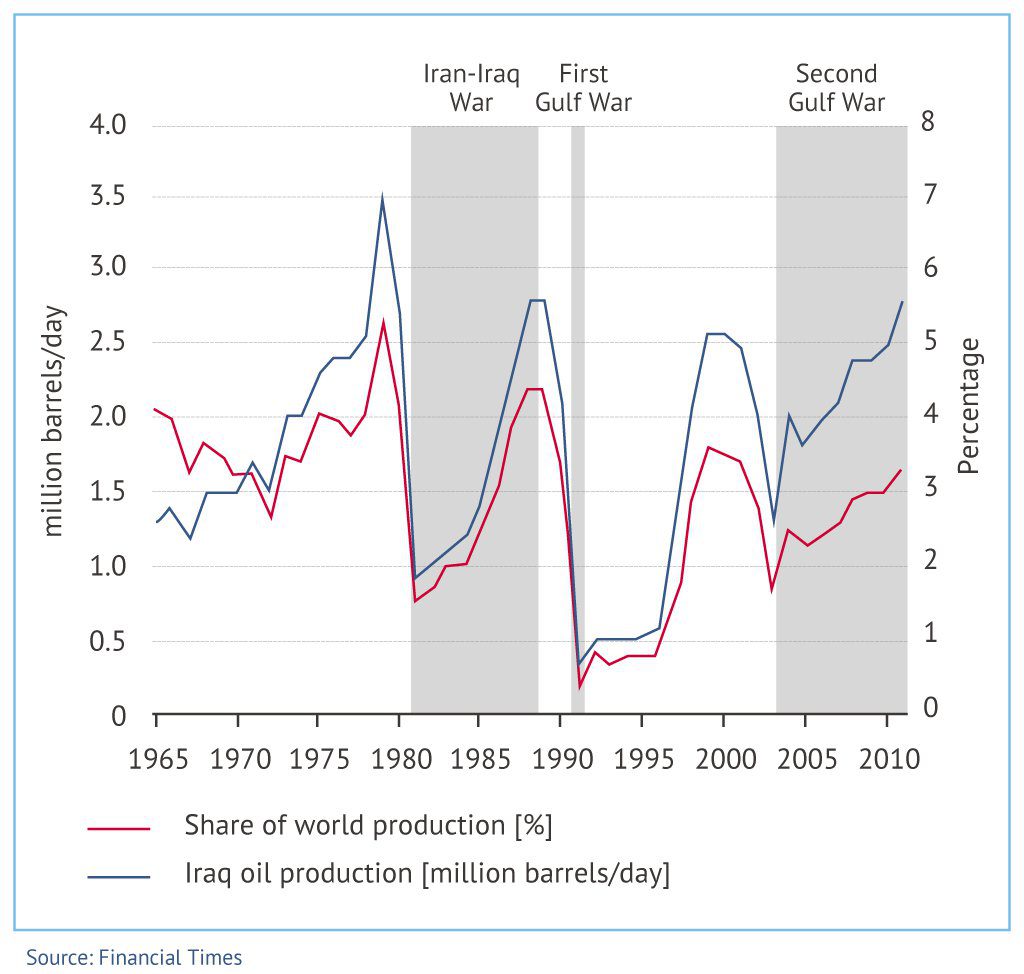

The orderly production schemes of some of its neighbours, notably Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Qatar and the UAE, seem always to have eluded Iraq. Indeed, it has been a volatile and resource-rich Iraq that has been at the centre of three shocks to the global crude-oil markets, the underlying causes of which do much to explain the present state of the country’s energy sector. this text.

Iraq's Energy Sector in Context

Security-related shock 1: 1980

Paradoxically, the country’s oil wealth enabled Saddam Hussein, its long-time ruler, to fund a military campaign to take over Iran’s south-western oilfields in the wake of the Iranian Revolution, when much of Iran was in disarray. The ensuing 1980 Iran-Iraq war was a tragedy of vast proportions; not only were lives and money lost, but Iraqi and Iranian oil-production installations were seriously damaged.

Security-related shock 2: 1992

In 1992, Saddam Hussein’s regime again sought to overwhelm the oilfields of a neighbouring state, in this case Kuwait. The event alarmed oil consumers beyond the Gulf and culminated in the mobilization of the United States military. Saddam’s army was quickly repelled, and fears that his military machine might continue further than Kuwait and into the oilfields of Saudi Arabia were put to rest.

This, however, marked the beginning of a large American troop presence in the heart of the Arab world. In both instances – the Iran-Iraq war and the first Gulf war – production levels contracted severely in both the aggressor’s state and the victim’s.

The consequences for the oil and gas sector have been damage to oilfields, limited oilfield investment and export restrictions. A turnaround following these years of violence eluded Iraq; more than 30 years passed before it was again able to reach production levels achieved just before the Iran-Iraq war (see section 2).

Security-related shock 3: 2003

he overthrow of Saddam Hussein’s Baathist regime, while effectively preventing Iraq from engaging in military attacks against its oil-rich neighbours, has brought its own challenges. Belligerence outwards has perhaps distracted world opinion from the fault lines existing within the country.

With the removal of the regime’s monopoly on force, the country’s internal divisions were exacerbated, bringing the security challenge to the fore and severely compromising the notion of an Iraqi state (the present state of affairs is discussed in section 4). The health of this sector directly tracks the country’s development.

The energy sector of any country, including upstream oil and gas exploration activities, production, transport, refining and electricity generation, requires high levels of investment over long periods.

Iraq’s population currently stands at 34.8 million, and the stabilization of the country’s oil and gas production, which will enable production to be increased, is key to improving not only global energy-market stability but also the standard of living of Iraqis. Iraq is highly dependent on revenues from its oil and gas exports.

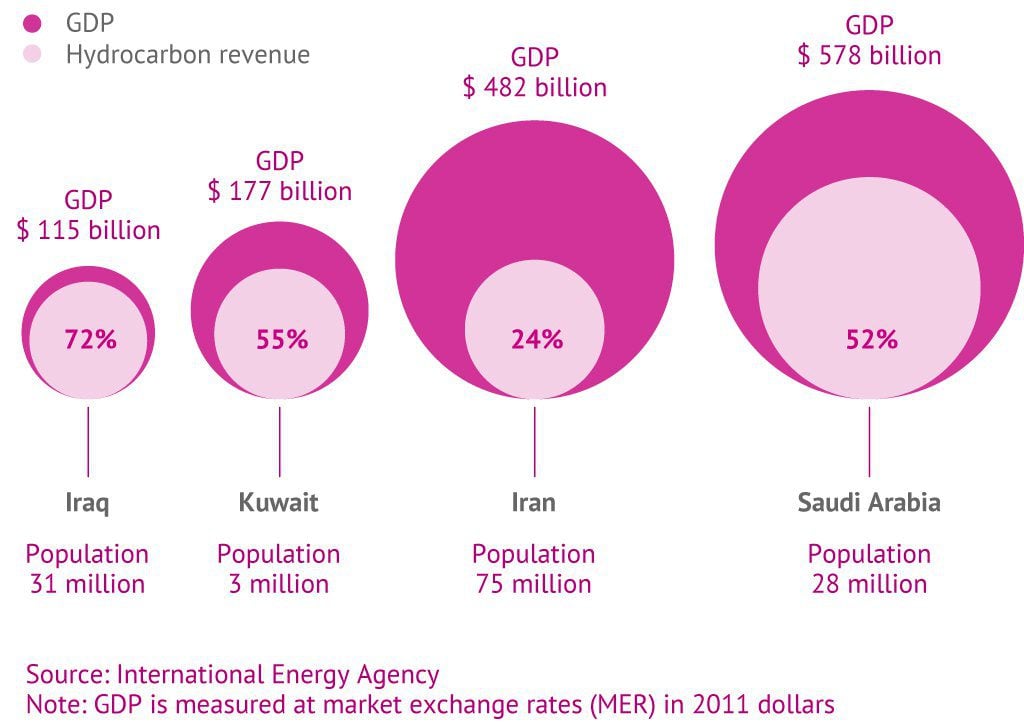

In 2011, for example, oil revenue accounted for about 95% of government income and more than 70% of Iraq’s GDP. These figures are high, even by the standards of other resource-rich countries in the Middle East (Figure 2). These numbers, while problematic in themselves, demonstrate the importance of the hydrocarbon sector to Iraq and at least the initial phase of its development, if it is to move in the direction of some of its affluent neighbours.

Oil and Gas

The successive episodes of violence and instability that have stunted the growth of Iraq’s oil production mean that the country remains a frontier in the global oil-supply economy, in terms both of rehabilitation and extension of existing production infrastructure and the potential for new finds, when exploration resumes in earnest.

The degree to which Iraq has lacked modern production capability is illustrated by the fact that it was only in March 2014 that it regained its historical peak of production previously achieved in 1979 – an average of 3.5 million barrels per day (mbpd).

Iraq’s hydrocarbon reserves are enormous, and its past production does not reflect its actual production potential (section 2). The combination of its great geological potential and the persistent suppression of exploitation prompted the International Energy Agency (IEA) in 2012 to focus much of its flagship publication, World Energy Outlook, on Iraq (see Iraq Energy Outlook 2012).

The thinking at the time may have been that the influx of foreign capital and expertise evident in a string of ambitious contracts proved the ability of the new Iraqi state to accommodate intensive production plans, a circumstance that had eluded Iraq for many years.

Having examined 46 major Iraqi fields, the IEA concludes that – if all proceeds according to the current schedules as stipulated in existing contracts – oil production capacity in Iraq could reach 14.6mbpd by 2020. The IEA’s central scenario, however, posits that oil production would be more likely to increase to approximately 6mbpd in 2020 and 8.3mbpd by 2035.

These production increases are expected to be driven mainly by super-giant fields (with reserves of more than 5 billion barrels [bbbl]) in the south (section 2.2). These estimates formulated in 2012 have since been revised for reasons elaborated in this report and may be revised further in light of the current security situation (section 4).

Iraq also holds major gas reserves, even though its gas production lags considerably behind oil-production levels. According to estimates by Oil & Gas Journal and BP (formerly British Petroleum), Iraq’s proven dry natural-gas [1] reserves in 2010 were 3.17 trillion cubic metres (m3).

Though Iraq’s reserves are small compared to its neighbours such as Iran and Qatar and even Saudi Arabia, they are still enormous by global standards: the tenth largest in the world, more than those of Norway and the United Kingdom combined. Most proven reserves (71%) are in the well-explored southern region, which is where most of Iraq’s gas is produced from associated fields [2].

Another 9% is dome gas [3], mainly in the northern oilfield of Jambur, and the remaining 20% is free gas [4] contained in nine gas fields located mainly in north-eastern Iraq. Among non-associated fields, only one is currently producing: the al-Anfal field, at about 5.7 million cubic metres (MCM) per day. After an (ultimately unsuccessful) earlier gas bidding round for three large non-associated fields, a new round commenced in October 2010.

Natural gas production is important for electric power generation and industry, but much of the gas produced in associated fields is simply flared (burnt as waste) in the process of oil production. Flared gas in Iraq averaged at least 20MCM per day in 2010. This represents about 32% of total daily gas production. According to a report issued by the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Iraq flared the fourth-greatest volume of gas of any country in 2010.

This is an economic waste, as natural gas could do much to improve the efficiency of electrical generation and increase oil revenues to the state, as Iraq, like many other Middle Eastern countries, produces electricity from oil, effectively paying a premium for electricity, as the revenues from the oil used for electrical generation are foregone.

In summary, Iraq’s ambition to expand its oil and gas output over the coming decades is not limited by the size of its hydrocarbon resources nor by the costs of production, which are among the lowest in the world. Rather, it is limited by the ability of the state to cooperate with industry to see scheduled investments through to completion, with all the security and political confidence that requires.

Contracts and field-development plans to date do imply an extraordinary increase in production, but the way in which these plans evolve in practice will be determined by the speed at which impediments to investment and other production constraints are removed, clarity on the legal arrangements between Baghdad and the Kurdish Regional Government (KRG) is reached and security requirements are met – requirements which have so far been met only partially and whose permanence is in doubt.

Present Iraqi Legal Environment and its Role in OPEC: Political-Economic Nexus

The nexus between politics and hydrocarbon production in Iraq is apparent primarily in the interaction of oil production with the vagaries of the Iraqi state and secondarily with regard to its position in the OPEC cartel. Iraq has, however, been outside the OPEC quota system [5] for many years, given that the sanctions regime, war and insurgency meant that Iraq was unable to achieve production in line with its reserves, as the other OPEC member countries have.

Iraq was one of the first countries in the region to nationalize its oil- and gas-producing infrastructure in 1972, with the establishment of the Iraq National Oil Company (INOC). From that point until the fall of Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein in 2003, Iraq saw very little involvement by foreign companies. With the overthrow of the Baathist regime, ownership changes and operating practices ensued, in accord with the country’s political reorganization.

The current legal framework for the energy sector exists in the 2005 constitution, which establishes a federal democratic system of governance, with the KRG area accorded the status of a federal region. The key institutions in Iraq’s energy sector are the Ministry of Oil (for the hydrocarbons sector) and the Ministry of Electricity (for the power sector), both of which report to the Deputy Prime Minister for Energy.

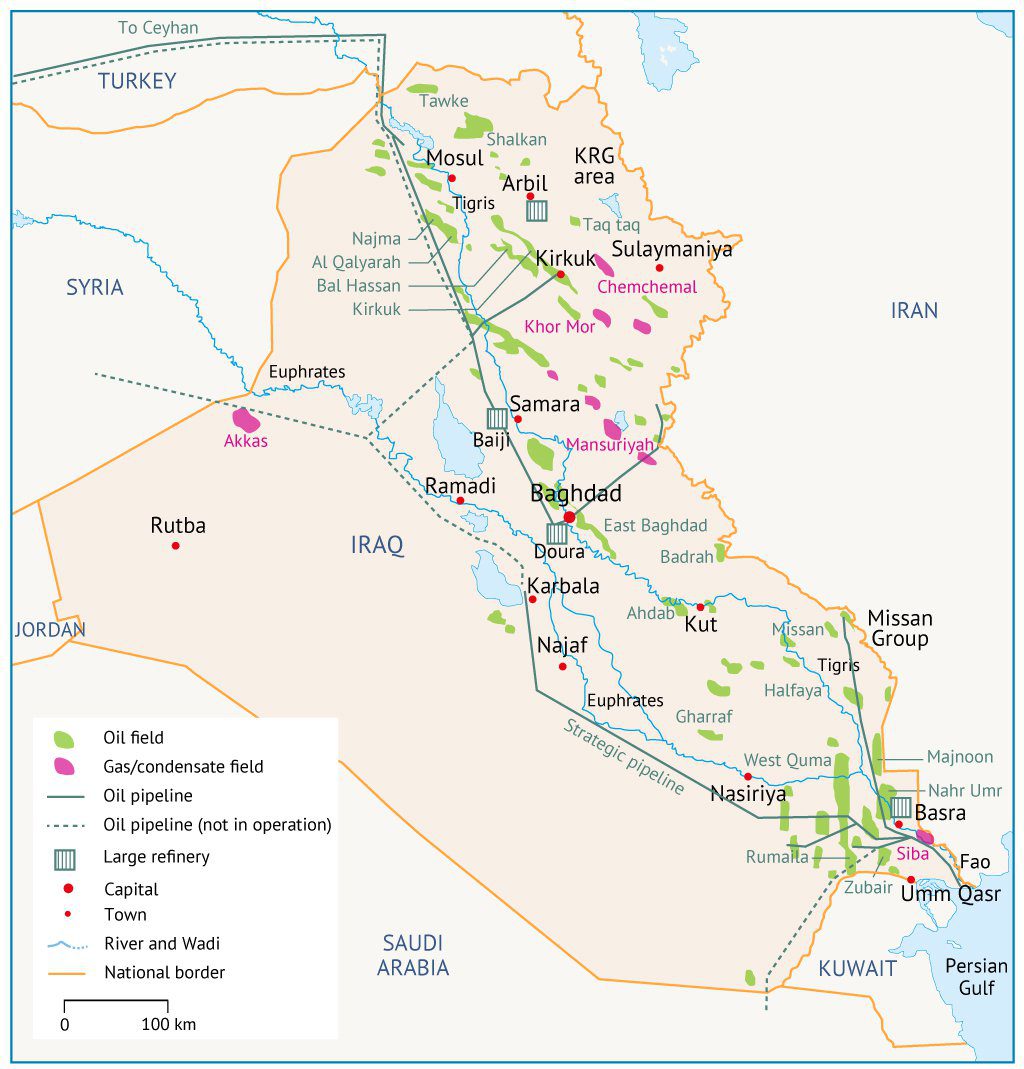

These ministries combine policy-making, regulatory and operational functions, including, in the case of the Ministry of Oil, direction and supervision of regional state-owned oil-production companies (the South Oil Company in Basra, the North Oil Company in Kirkuk, the Missan Oil Company in Missan and the Midland Oil Company in Baghdad), the State Oil Marketing Organization (SOMO), which manages the exports and imports of crude oil and oil products, and the South and North Gas Companies, which process gas.

The delay in passing comprehensive hydrocarbon laws spanning Iraq more broadly (especially with regards to the KRG) means that, for the moment, a federal system of resource development (based on technical-service contracts, which provide to the contractor a fee per barrel of oil produced as remuneration for work done, although the timing and nature of this remuneration vary considerably) coexists uneasily with the approach followed by the KRG (based on production-sharing contracts, which provide returns based on the value of the oil and gas found or produced).

The latter is consistent with its own legislation of 2007, whose legitimacy has been contested, on several occasions, by the federal government. The proposal of the so-called Hydrocarbon Law, which would govern contracting and regulation, has been under review in the Council of Ministers since 26 October 2008 but has not been passed.

Despite the lack of a Hydrocarbon Law, however, the Ministry of Oil signed long-term contracts with international oil companies (see section 2.2.1), beginning in 2008. Indeed, it has been basic progress in this area that has enabled production gains in Iraq that previously eluded the Baathist regime.

As Iraqi production increases, concerns over its future role in OPEC grow. Hussain al-Shahristani, the oil minister at the time, commented that if Iraq were to rejoin OPEC’s quota system in the future, it would not be until Iraqi crude oil production reached at least 4mbpd. As he stated in October 2010: “[We] think Iraq has been deprived of its fair share of the world energy market, oil market, for many years, and has to be compensated in addition to its reserves and production capacity.”

Upstream: Production, Reserves and Exploration

Iraq revised its estimate of proven oil reserves from 115 billion barrels (bbbl) in 2011 to 141bbbl as of 1 January 2013, according to the Oil and Gas Journal. The new reserve estimate gives Iraq the fifth-largest proven oil reserves in the world and the third-largest conventional [6] proven oil reserves, after Saudi Arabia and Iran.

According to data from the Ministry of Oil, Iraq’s proven reserves are located in 66 fields, with total technically recoverable oil in these fields exceeding 500bbbl.

Among the 66 known oilfields, only 20 are currently producing. Included in these fields are several – exceptionally rare – super-giant fields:

West Qurna (43bbbl reserves, south)

Majnoon (12bbbl reserves, south)

Kirkuk (9bbbl reserves, north)

East Baghdad (8bbbl reserves, central)

Nahr Umr (6bbbl reserves, south)

Halfaya (nearly a super-giant, with reserves of 4.1bbbl, south)

Zubair (nearly a super-giant, with reserves of 4bbbl, south)

Jeddah (Saudi Aramco) 85,000bpd

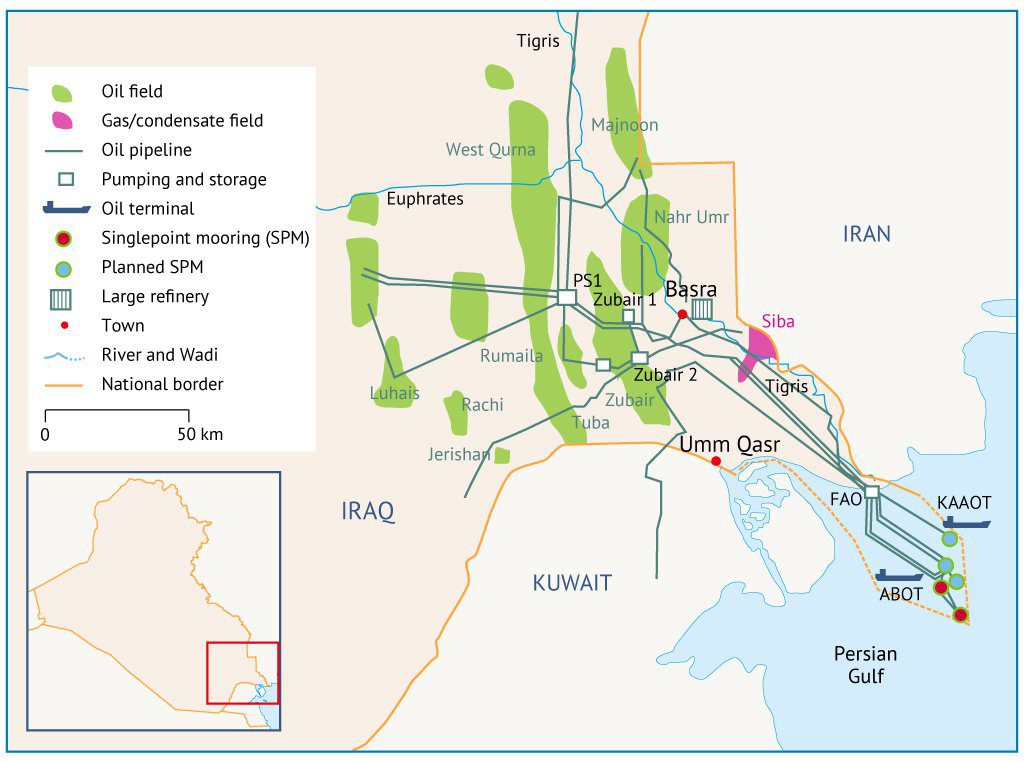

The Rumaila field, located in south-eastern Iraq (Basra Governorate), is the largest active field in the country, producing some 1.3mbpd in 2012. West Qurna, Zubair and Kirkuk (located in the north) are also significant contributors. Rumaila, West Qurna, Zubair, Majnoon and Nahr Umr, all concentrated in the Shia-majority south-east of the country, account for 60% of Iraq’s total proven reserves.

The southern fields are all within easy reach of coastal export facilities, keeping the primary export pipelines relatively short (Map 2). Such proximity to an international port is an important consideration, not only for getting the crude to market but also for bringing in equipment, in this case via the Shatt al-Arab waterway that runs up from the Gulf to beyond Basra. This ease of access is in marked contrast to the logistical difficulty of bringing heavy equipment into many other parts of the world, for example, the Caspian region and northern Russia.

The super-giant fields being developed in the south are some of the largest in the world, bringing large economies of scale to their exploitation. Moreover, the geology is less complicated than that of major projects elsewhere in the world, for example the Kashagan field in Kazakhstan, where the reservoir is deep and at very high pressure, or deepwater pre-salt [7] developments in offshore Brazil. Iraq’s fields are all onshore and are often, as in the case of the fields around Basra, located in relatively unpopulated and flat terrain, reducing the costs of wells, pipelines and other facilities.

Northern Iraq is dominated by the super-giant Kirkuk field and those fields falling within the jurisdiction of the KRG. The KRG has stated that oil resources in the region amount to 45bbbl and, because of favourable contract terms, are of interest to many foreign operators.

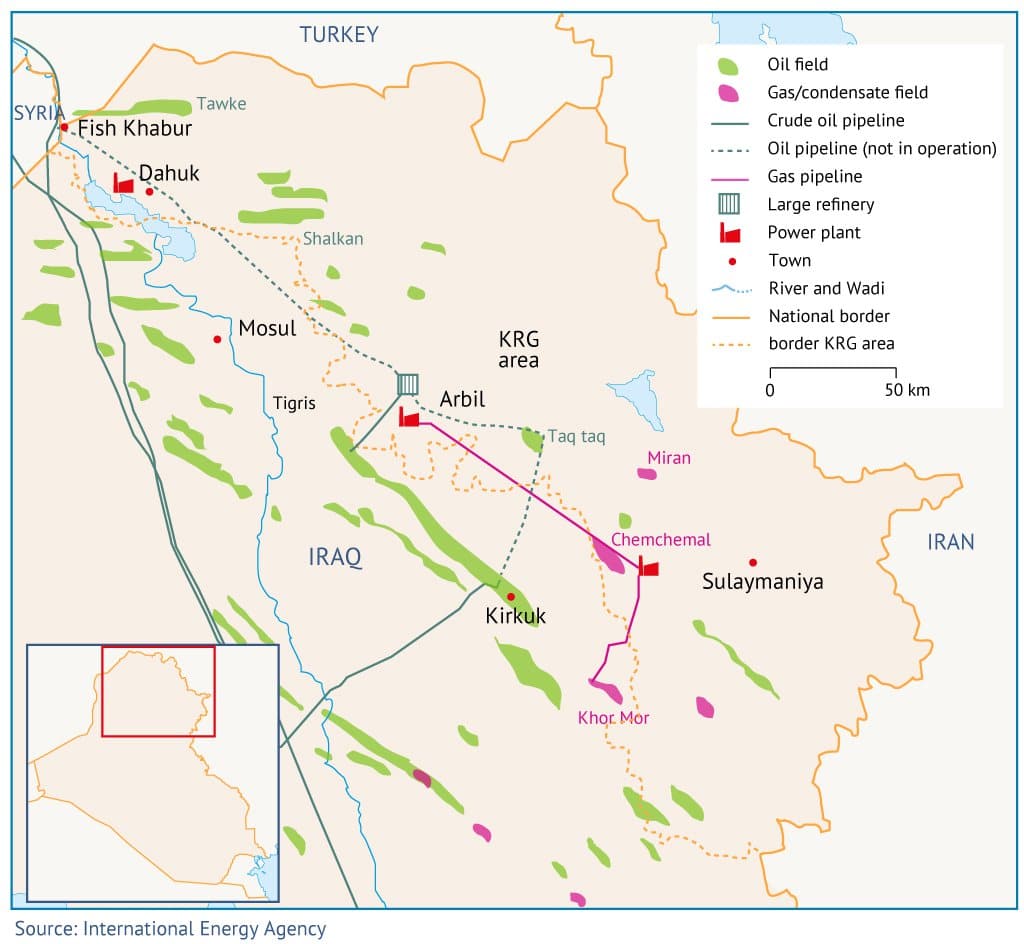

There are currently five fields producing under contracts awarded by the KRG: Tawke, Taq Taq, the Khurmala dome of the Kirkuk field, Shaikan (in early production) and the Khor Mor gas field, which produces condensates (Map 3). These are liquids or liquids under pressure (propane, butane, etc.) that are produced at gas wells.

Iraq’s largest reserves are located in the south, near the Persian Gulf, and in the north, near the city of Kirkuk, but there are smaller fields in other parts of the country, with the exception of Anbar province, in the west. As the largest production commitments were volunteered by international companies during the licensing rounds and subsequently incorporated into binding technical-service contracts, the Ministry of Oil has good reason to expect a large increase in production capacity from fields covered by technical-services contracts alone.

Foreign Oil and Gas Company Activity

There is no definitive answer to the question of what role the nation’s oil wealth played in the US-led invasion of Iraq in March 2003 and the subsequent overthrow of Saddam Hussein’s Baathist regime, but it was to be expected that increased amounts of Iraq’s oil would be developed by foreign oil companies when Iraq’s oilfields were no longer under the control of that regime.

It must thus have been at least a motivating factor, given the global economic interest in increased oil and gas production and the frustration with Saddam’s regime. Under the first phase, companies bid to develop giant oilfields that were already producing.

With the preliminary outlines of a new government having been established in 2005, the planned pull-out of American forces and decreased security risk from insurgency, field development contracts were put up for auction. Under the first phase, companies bid to develop giant oilfields that were already producing.

Phase-two contracts were signed to develop oilfields that had been explored but not fully developed or producing commercially. Contracts for the two phases cover oilfields with proven reserves of more than 60bbbl. If these fields were to be developed as initially planned, they would increase total Iraqi production capacity to almost 12mbpd, or about 9mbpd above 2012 production levels, but contract implementation has clear challenges.

Iraq has since held a third bidding round for natural-gas fields, and a fourth for fields that contain predominantly crude oil. Nineteen technical-service contracts have been awarded by the federal government to date, each to a consortium led by an international operating company. Iraq’s state-owned operating companies have a 25% stake in each of these consortia.

Production in 2010 averaged about 2.36mbpd. It has since increased due to these contracts. In fact, four projects (Ahdab, Rumaila, West Qurna Phase I and Zubair) have already reached the initial threshold production, collectively producing 2.05mbpd, the lion’s share of Iraq’s daily production. Ahdab was awarded separately to PetroChina in 2008, with initial target production set at 25 thousand barrels per day (kbpd), June 2012 production achieving 129kbpd, with the plateau target set at 140kbpd.

In most cases, the bidding process and hard bargaining have been followed by contract implementation, but some companies have explicitly or implicitly reviewed their positions in the south. Statoil has sold its stake in West Qurna Phase II. ExxonMobil, operator of West Qurna Phase I, has sought to pursue exploration opportunities in the KRG area, as have Total (part of the consortium for the Halfaya field, with PetroChina) and Gazprom Neft.

ExxonMobil’s decision to invest came just weeks before an end-of-December deadline for the US to withdraw its troops from Iraq. The federal government has made it clear that no company with activities in the KRG area is allowed to bid in the national licensing rounds for projects in the rest of Iraq, but the implications for companies with existing contracts are unclear.

Nevertheless, later rounds have demonstrated strong interest in production-sharing agreements in the KRG [8]. The KRG effectively challenged the authority of the national government when it signed oil-production-sharing agreements with ExxonMobil to develop six blocks in northern Iraq, some of which are in disputed border areas.

ExxonMobil’s move is especially momentous given it was the company that led the first US consortium to re-enter Iraq’s oil industry in 2009, after more than 30 years, by agreeing to develop the giant West Qurna I field. Other super-majors, such as BP and Royal Dutch Shell, have hesitated to sign contracts for fear of antagonizing Baghdad, which has said it believes the contracts to be illegitimate.

Indeed, ExxonMobil’s (announced) intention to pull out of the massive West Qurna I project [9] underscores the tensions in dealing with Baghdad and the displeasure of some prominent super-majors with contract terms compared with those offered by the KRG.

The KRG has awarded about 50 contracts for hydrocarbon exploration and development, mostly to medium-sized international companies. Since 2010, some large international oil companies have also begun to The KRG has awarded about 50 contracts for hydrocarbon exploration and development, mostly to medium-sized international companies.

Since 2010, some large international oil companies have also begun to acquire licenses from the KRG, including Murphy Oil and Marathon in 2010, followed by Hess, Repsol and ExxonMobil in 2011, and stakes in existing licenses acquired in 2012 by Chevron, Total and Gazprom Neft. Most recently, Genel has entered serious talks with the KRG.

Even before the latest security problems (section 4), Iraq faced steep challenges in meeting its ambitious production targets. This was due to the infrastructure required to realize the massive increases in production. Baghdad has subsequently reduced its 2020 production target to 8.5-9.0mbpd. The central government initially expected production to reach 12mbpd from its giant fields alone, slated to be developed in the first two licensing rounds.

These estimates, however, were lowered in June 2014, following revisions to contract terms. A final agreement has been reached with Eni to lower the production target for the Zubair field to 0.85mbpd by 2020 from the 1.1mbpd target for 2017. Lukoil has reduced its terms for West Qurna II to 1.2mbpd from 1.8mbpd. BP and CNPC have agreed, in principle, to cut the production target for the giant Rumaila field to 2.1mbpd from the original 2.8mbpd by 2020.

Revision negotiations for West Qurna I and Majnoon are currently underway. The contracts for the smaller fields are not expected to change, except for those facing security challenges. The Angolan state oil company Sonangol has exited its contracts for the Najma and Qayara fields in Nineveh, which borders Anbar province, citing security risks.

Mid-Downstream: Refining, Transport and Export Capacity

Oil and gas available at the well head says little about takeaway capacity and refinery capacity, that is, the ability to bring crude oil to market and to refine crude into usable products. The oil products produced by Iraq’s refineries fall well short of its domestic needs and the possibilities afforded by modern, more complex refineries. [10]

Iraqi Refinery Capacity

Main Pipeline Infrastructure

(Iraq-Turkey) pipeline, which transports oil from northern Iraq to Turkey’s Mediterranean port of Ceyhan. This pipeline route consists of two parallel pipelines with a combined nameplate capacity of 1.65mbpd. Only one of the twin pipelines is operational.

The maximum available capacity of this line is, according to the Ministry of Oil, 600kbpd, much less than the nameplate capacity of 1.65mbpd. In order for the route to reach full capacity, Iraq would need to receive oil from the south via the Strategic Pipeline or increase northern production threefold.

The Strategic Pipeline has been offline, because it needs repairs and is at significant risk of sabotage. Iraq and Turkey have held discussions on increasing pipeline capacity along this route, but implementation timelines are unknown and the current risks are yet to be addressed.

The Kirkuk-Baniyas (Syria) pipeline, with a design capacity of 700,000bpd, has been shut down, and the Iraqi portion has been unusable since the 2003 war. Discussions have been held between Iraqi and Syrian government officials about re-opening the pipeline.

The Russian company Stroytransgaz also expressed interest in repairing the pipeline, but this plan has not moved forward. Furthermore, given the civil war in Syria, such a plan does not seem feasible in the medium term. The 1.65mbpd Iraq Pipeline to Saudi Arabia (IPSA) has been closed since 1991 following the first Gulf war, and there are no plans to reopen it.

There have been several other notable proposals to increase flows from northern oilfields and to diversify away from reliance on the port of Basra. The Kurdistan Iraq Crude Export (KICE) pipeline has been proposed to transport 420,000bpd of crude oil from fields in the Kurdish region to the border with Turkey, where it may subsequently connect to the Kirkuk-Ceyhan pipeline.

The southern pipeline proposal is in two phases: the first phase consists of building a 2.25mbpd pipeline from Basra north to Haditha, in Iraq’s Anbar province. The second phase is the proposed construction of a 1mbpd crude-oil pipeline from Haditha to the Jordanian port of Aqaba, on the Red Sea. Given the security situation in the country and in neighbouring Syria, this pipeline no longer seems feasible in the medium term.

Electricity

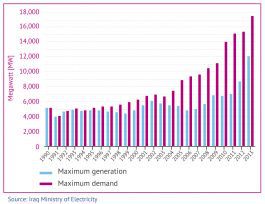

Iraq’s power supply is able to meet only about 60% of the country’s demand (with some 20% of the population having no access to electricity at all), although the available supply varies somewhat by area and season.

The Kurdish region now has 1,250 megawatts (MW) of power, and the rest of the country has about 4,800MW, when plants are functioning properly. Up to 1,000MW is imported from Syria and Iran, with Syrian imports down due to the civil war raging there.

Security Issues and the Threat to Iraq’s Energy Sector

Since the former al-Qaeda branch Islamic State (IS) seized much of Iraq’s Sunni regions in 2014, questions have arisen over the threat it poses to Iraq’s development and its oilfields.

The present situation differs in several important respects from the previous extremist insurgency that followed the toppling of Saddam Hussein in 2003.

To begin with, the present insurgency does not have its roots simply in domestic unrest with the stated aim of ousting an occupying force.

Rather, this insurgency stems from divisive politics of an inequitable central government in Baghdad, general terrorist movements that thrive in the chaos of war zones and the power vacuum in Syria, with which Iraq shares a long border in the west (for more information, see Country Report: Syria).

The removal of the Baathist regime undoubtedly exposed the fissures hidden beneath the surface of Saddam’s iron-fisted security apparatus. However, the ensuing violence might have been anticipated had those in charge understood the sectarian divisions in Iraq and how they were likely to be exacerbated by the collapse of the rule of law following the invasion. The al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI) movement can thus be viewed as a direct consequence of the invasion; it could hardly have come into existence otherwise.

The pull-out of American troops has quelled the uprising of Shiite militias ardently opposed to a non-Muslim military presence in the country, but the Sunni-rooted movement has persisted and even grown. This can be attributed to the terrorist inclinations of the hard-core AQI group but, even more, to the marginalization of the Sunni population in western Iraq by the Shia-majority government in Baghdad.

In the apocalyptic environment of years of war, AQI has shifted from an insurgent group battling American military patrols into a cross-border entity approximating a state, one purporting to represent the interests of an oppressed Sunni Arab population while maintaining a “pure” form of Islamic government.

The IS media stunt of bulldozing a stretch of the Syria-Iraq border and declaring an “end to the Sykes-Picot Agreement” and the invention of a new caliphate after seizing Mosul (Iraq’s second-most populous city), marked a new chapter in the region’s history.

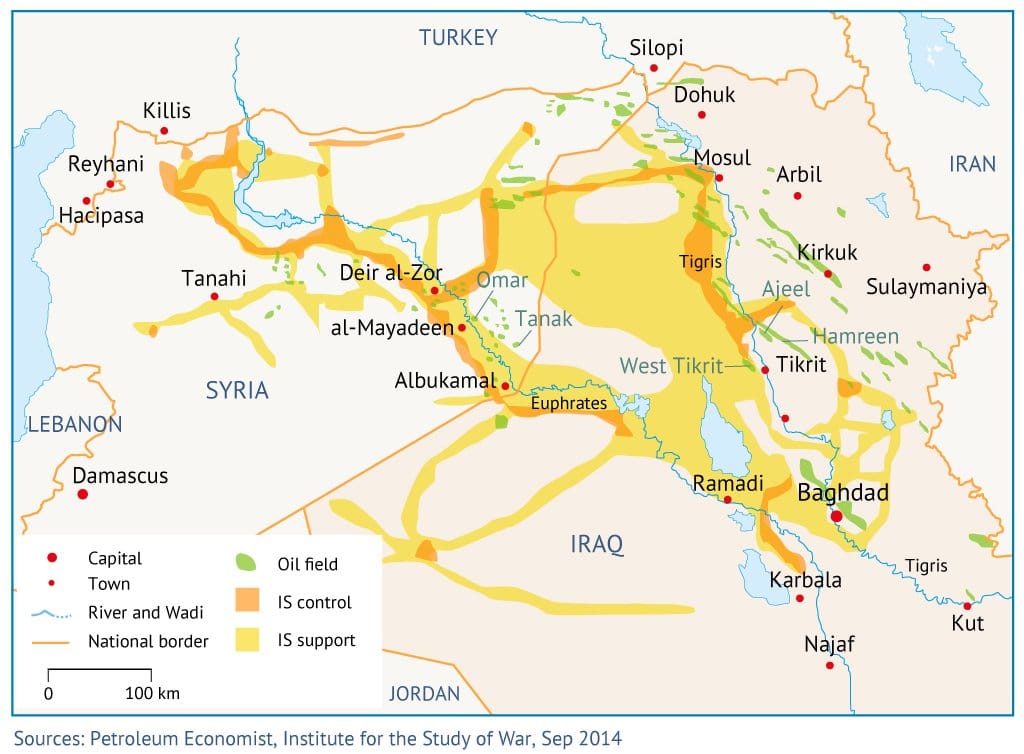

The present situation thus reflects a much deeper issue than insurgency. It brings into question the future of Iraq, as well as that of Syria and how the world will deal with increased terror threats from the first-ever Islamic terrorist state. Map 5 shows the presence of IS forces just before the beginning of US-led coalition airstrikes; approximately one third of Iraqi territory was under direct or indirect IS control before the start of the coalition airstrikes.

Oil and Trends Toward De Facto Statehood in the Levant

The future of the Iraqi state is intricately entwined with its oil wealth. With a war being fought against IS on what is effectively two oil-rich fronts – one controlled by a semi-autonomous Kurdish population in the north and the other by a largely Shiite population in the south – the former business-as-usual bickering over oil revenues is rendered of secondary importance.

Much more pressing is resolving the situation on the ground, by continuing the fight against IS and financially sustaining the military resistance as well as supporting the fiscal plans of the respective regions.

In the case of Baghdad, this means addressing the grievances of the marginalized Sunni population currently exposed to IS in Iraq’s western provinces or risk losing it. The manner in which these two challenges are addressed will determine the fate of the Iraqi state.

It remains to be seen whether Iraq will continue the de facto fragmentation into a Kurdish northern state (incorporating Syrian Kurds on Iraq’s north-west border as Syria also fragments; see Country Report: Syria) and a predominantly Shiite state with the Iraqi Security Forces (ISF) as a sectarian instrument alongside the militias or whether the unity government elected in April 2014 will bring Iraq together against IS.

As the Kurds fight IS in the north, the incentive to break away from Baghdad is not trivial. With a limited ISF presence in the north, the Peshmerga (Kurdish military) have seized Kirkuk and the super-giant Kirkuk oilfield (see Map 5).

Kirkuk’s truck export route to Jordan through Anbar (typically moving 10,000bpd) has been cut due to the presence of IS, but some 15,000bpd of condensate and 20,000bpd of crude oil are being exported to Turkey by truck. Furthermore, the KRG is also looking to build its own pipelines to export crude oil directly via Turkey, bypassing the national export pipeline system. Although Turkey has not officially agreed to this plan, the Anglo-Turkish company Genel Energy plans to build the 420,000bpd Kurdistan Iraq Crude Export (KICE) pipeline that will connect its fields in the Kurdish regions in northern Iraq to the Turkish border. The KRG has also explored the possibility of supplying natural gas to Turkey.

Agreement between Baghdad and KRG

In the second half of 2014, however, the heated environment spurring the Kurds towards secession from Iraq cooled, simply because the Kurds face a difficult choice: leaving Iraq means losing revenues from the central government. This loss would be disastrous in the near term, as an independent Kurdistan would make under $7 billion per year, almost a third less than they received from just 12% of Iraq’s total oil revenues.

This is not economically sustainable, especially at a time when Prime Minister Nechirvan Barzani’s government faces the additional financial strain of aiding beleaguered Syrian Kurds and the Kurdistan region becomes a dumping ground for the rest of Iraq’s problems.

Implications for Foreign Operators

It is unlikely that the IS militants will be able to overwhelm key Shiite territories or the Kurdish federal region militarily, especially with the initiation of coalition airstrikes against IS. But there is still the risk of one-off acts of terror that may include sabotage, kidnapping and other threats to Iraqi energy installations and personnel.

This is not to deny that oil projects in Iraq are among the technically more straightforward and lowest cost in the world, in terms of the capital cost per unit of new production capacity and operating expense. Many companies will remain interested in the prospect of high volumes, in the knowledge that Iraq’s fields are of such size and quality that there is relatively little technical, price or exploration risk.

That said, it is likely that capital that would otherwise have been allocated to investment may now be diverted to combat IS. Adding security, as is likely to be necessary, will raise the operating costs and lower the profitability for the operators and the people of Iraq.

With nearly two million internally displaced persons now in Iraq, the majority in Kurdish territories, the KRG is facing a fiscal burden of almost $300 million per month, and the recent decline in oil prices means the Kurds will need to produce up to twice as many barrels per day to break even, even selling at market prices – the KRG has so far sold oil at great discounts, mainly because traders view the purchase of KRG oil as a risk in the face of legal objections from Baghdad.

In Arbil, the lack of petrodollars coming from Baghdad – and too few coming from the sale of Kurdish oil – has left a multitude of civil servants, including 180,000 Peshmerga fighters – without salaries for months. Perhaps triggered by this situation, the government of Iraq and KRG signed an agreement in November 2014 to ease tensions over Kurdish oil exports and civil-service payments from Baghdad.

Hoshyar Zebari, Iraq’s deputy prime minister and finance minister, said the central government had agreed, for the time being, to resume payments from the federal budget for Kurdish civil servants’ salaries. Zebari, a Kurd, described the step as a “major breakthrough” that would reduce friction between the KRG and Baghdad. He said the payments would cover October (previously outstanding and a major source of contention) and then November.

Under the agreement, Iraqi Kurdistan will commit to the federal budget 150,000bpd of oil exports, equal to about half of its overall shipments. The KRG is apparently taking advantage of Iraq’s new unity cabinet, which includes Shiites, Sunnis and Kurds. Perhaps the legacy of Iraq’s former oil minister, Hussain al-Shahristani, who pursued an aggressive centralized oil policy disliked by the Kurds, is fading.

The appointment of Adel Abdul Mehdi as the new oil minister has helped to sway the Kurds, as he enjoys close relations with Barzani’s party. Finally, 17% of Iraq’s oil and gas revenues are slated to be sent to Arbil, if a longer-term agreement can be reached. In light of the development plans for the fields in Basra, this is a slice of a large pie.

Unsurprisingly, energy also figures prominently in the activities of IS. Territory currently controlled by IS in Iraq is predominantly in the western Anbar province, which, in terms of hydrocarbon reserves, pales in comparison to the Kurdish-controlled north and predominantly Shia-controlled south. However, there is oil to be found in territories controlled by IS in both Iraq and Syria.

Maplecroft, the risk management firm, estimates that IS now controls six out of ten of Syria’s oilfields, including the big Omar facility, and at least four small fields in Iraq, including those at Ajeel and Hamreen.

Revenue streams associated with illicit production are aided by the long-standing networks of black-market oil sales and smuggling in the Levant. The imposition of UN energy sanctions on Iraq in the 1990s resulted in a robust network of smugglers, traders and bootleg refineries.

“The fact that Iraq was under sanctions for so long led Kurdish and Iraqi businessmen to fill a vacuum and create smuggling networks for Iraqi oil,” says Valerie Marcel, a Middle East and Africa energy specialist at Chatham House. “Turkish, Iranian, Syrian, Iraqi networks have grown because of decades of bans on exports.”

The Energy Information Administration (EIA) and the Iraq Energy Institute have estimated IS production at 50kbpd in Iraq and 30kbpd in Syria, implying earnings of $3.2 million per day when sold at the black-market price of $40 per barrel. As such, these oil installations have been prime targets for the US-led airstrikes initiated in August 2014.

[1] Dry refers to strictly gaseous deposits (methane) containing no liquid substances such as condensate.

[2] An associated field is one where oil and natural gas both exist in separate strata. Extracting gas for use from such fields can be more complicated and expensive than extracting gas from non-associated fields. Yet in order to get at the oil, the gas must be removed, which is often done by flaring. Although most associated fields are in the south, there are a few in the north, such as the Kirkuk field.

[3] Gas contained in geological formations known as domes, which are large or elliptical structures.

[4] Free gas is gas contained in reservoirs where it is not absorbed in reservoir fluids or is itself in fluid state. Hence these reservoirs are relatively low pressure as they keep the gas in the gaseous state.

[5] OPEC has a system of production quotas, different for each country according to its reserves and level of petroleum development, which member countries are supposed not to exceed, in order to restrain global supply and maintain crude oil prices. When countries exceed their production quotas but do not admit doing so, this is called “cheating”.

[6] “Conventional” excludes what are commonly referred to as “tar sands” or “oil sands”, bitumen mixed with sand and clay that can be extracted with unconventional techniques and turned into synthetic crude oil. Canada and Venezuela have enormous reserves of these tar sands and, together with their conventional reserves, have among the largest oil reserves in the world.

[7] The pre-salt layer is a geological stratum underlying a salt formation, often containing significant amounts of hydrocarbon.

[8] “Iraq’s Appeal Wanes for Oil Majors” (March 2013)

[9] ”Exxon Looks to Quit Iraq Oilfield” (November 2012)

[10] The Iraqi government has stated that total refining capacity, under optimal (“nameplate”, or nominal) conditions, is 750,000bpd, although most analysts estimate it somewhat lower.