The radical Islamist group known as Islamic State (IS) currently controls vast areas of Syria and Iraq, from Aleppo in the west to Kirkuk in the east, with the exception of a few enclaves around Damascus and the Syrian-Lebanese border. Although large numbers of civilians fled those areas when IS moved in, around 7 million people still live under the group, according to the BBC. These include some 250,000 people in Raqqa, which IS declared its capital in August 2014.

IS fighters introduced themselves as men of God who had come to protect the people from the “infidel” regime, says Muhammad (also known as Abu Hilal) who ran a vegetable store in Raqqa before IS seized the Syrian city. “They told people that they would live safely under their ‘Islamic State,’ but it turned out that was not the case.”

Almost immediately, IS created an executive branch, called al-Hisba, similar to the security apparatuses found in dictatorial regimes. The branch is tasked with enforcing the group’s rules among civilians and does so brutally. The penalties for infringements range from hefty fines to floggings and beheadings. “It is extremely difficult to avoid the Hisba men,” says Abu Hilal, who fled to Istanbul in Turkey. “Anything you do could be a violation, including wearing a pair of jeans, smoking, shaving, using the internet or saying something that is considered offensive to the group or the religion. And the ready-made accusation is always apostasy.”

Abu Hilal never wanted to leave Raqqa. He says he had only considered fleeing his hometown when he heard IS was considering a conscription law that would require every family to send at least one male to join the ranks of the group’s fighters. The father of three sons, aged 18-24, he was terrified by the news. “I feared for my sons. I thought if they joined IS, they would be killed for a cause that is not ours, and in which we never believed.”

Maher al-Raqqawi, 28, left the Syrian city of Deir ez-Zor in January 2015 because IS had turned his life into “an unbearable hell. Everything is considered as violating sharia law, including painting, music, philosophy, sports, TV,” he says. “They forced people to go and pray in the mosque, and whoever did not received 40 lashes, which happened to me once. It is like living in the Middle Ages.”

Now living in Germany, al-Raqqawi says the IS-ruled regions are suffering a drastic shortage of basic commodities and services. “There is a serious lack of clean water and electricity; and the prices of basic commodities are skyrocketing.” When available, a home gas cylinder costs SYP 10,000-11,000 ($37-40), he says, while a litre of gasoline is SYP 300 ($1.20), a kilo of chicken is SYP 700 ($2.60) and a kilo of bread is SYP 300 ($1). Moreover, IS charges each household a monthly SYP 500 ($2) for local landlines, SYP 1,500 ($5.6) for water and the same amount for electricity, despite the fact that these services are available only a few hours a day. Although prices may look reasonable when converted to foreign currency, they are considerable in areas where incomes are less than $3 a day, according to al-Arabiya.net.

“Even worse, IS imposes heavy fines and taxes, although it is very hard to find a job except with the group itself,” al-Raqqawi adds. “Their fighters enjoy food, clean water and power generators, while the population suffers from the harsh living conditions.” The taxes include a monthly SYP 1,500-3,000 ($6-12) levy on stores and shops.

Commenting on the mentality of IS leaders, al-Raqqawi says that “they seek to forcefully convince everyone with their exclusive interpretation of sharia.” According to him, the people they consider pagans are spoils of war that can be bought and sold. These include followers of other faiths and Sunni Muslims who do not embrace the same convictions. “Anyone who does not pledge allegiance to their ‘caliph’ Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi is treated as an enemy.” He also describes how the residents of IS-held areas tried to hide their happiness on hearing the news of an international anti-IS alliance. However, he says that events took a grim turn when the strikes started. “Missiles rained down on civilian areas every day and destroyed the infrastructure. The strikes barely hit IS fighters who hid among civilians and in schools, which added to the suffering of the population.”

As for women, Abu Hilal says that IS treats them like slaves. “According to IS laws, a woman is not allowed to leave her house – except out of extreme necessity – without a male guardian who must be her husband, father, brother or son. And women who don’t wear a niqab [face veil] are whipped.” He adds that their clothes must also meet IS specifications of being loose, thick and uniformly black.

A number of media outlets have reported that IS has created a female brigade, mostly non-Syrian, tasked with finding, monitoring and arresting women. They also arrange marriages for IS fighters and provide intelligence on any attempts by women to smuggle weapons.

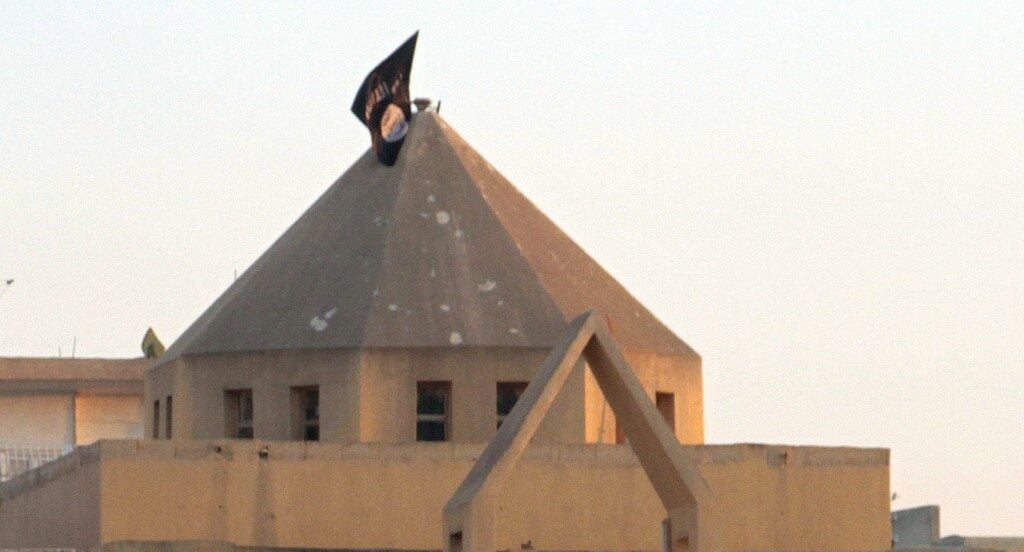

According to the London-based Syrian Observatory of Human Rights, IS has closed the banks in the areas it holds and reopened schools after replacing the national curriculum with its own. It has also banned all councils, gatherings, associations and flags.

Further aggravating popular discontent is the heavy presence of al-Muhajireen (foreign fighters). According to Abdul-Rahman, a peaceful activist still living in Raqqa, the Muhajireen control the city and enjoy preferential treatment from IS. “As they were establishing themselves, they started replacing the existing imams of mosques with foreign ones, mostly from the Gulf region, Afghanistan and Chechnya. The Muhajireen are spoiled: they get the best houses and cars while locals pay the taxes.” IS has given the homes of people who fled, mainly Christians, to the Muhajireen, he says. Those who own more than one house have also been forced to hand over their other properties to the fighters.

Abdul-Rahman estimates that IS is supported by no more than 10% of the population, plus a number of tribal leaders who maintain interest-based ties with the group. He adds that many Syrians living under IS risk their lives to expose its acts. “They take pictures and videos that show IS’s brutality.” He gives as an example a campaign that was launched by a number of activists on 16 April 2014 under the title “Raqqa is Being Silently Slaughtered”. Participants have been documenting IS’s crimes including public amputations and beheadings, as well as writing graffiti and distributing leaflets warning of the threat of the group.

“As activists, we tried to organize anti-IS protests here in Raqqa, but our attempts were violently repressed,” says Abdul-Rahman. He explains that the majority of his town’s residents oppose the Syrian regime but do not accept IS either. “The only reason that people are not moving is the fear that IS has managed to plant in their hearts through public torture and beheadings.”

Although Abdul-Rahman anticipates an anti-IS revolution at some point, he admits that it is difficult to predict how such an uprising would end. “Some people here are trying to adapt to the new, odd reality,” he says. “When we see that IS is powerful enough to hold its ground against the international alliance, the Kurds, the regime and the Syrian armed opposition, we ask ourselves: how would we, the unarmed civilians, be able to kick them out of our city?”