Introduction

In the 1930s – and for the next several decades, long before even larger oil reserves were found in the south – Kirkuk was the most important centre of Iraqi oil production and came to be of great strategic importance to successive governments in Baghdad, as well as to the Kurds. However, since the formation of Iraq in the 1920s, Kurds had been at war with those same governments over self-determination. Since the Kurds comprised a slight majority of the population of the province – confirmed by the last reliable census (1957) – steps have been taken since the 1930s to reinforce Baghdad’s grip on the area.

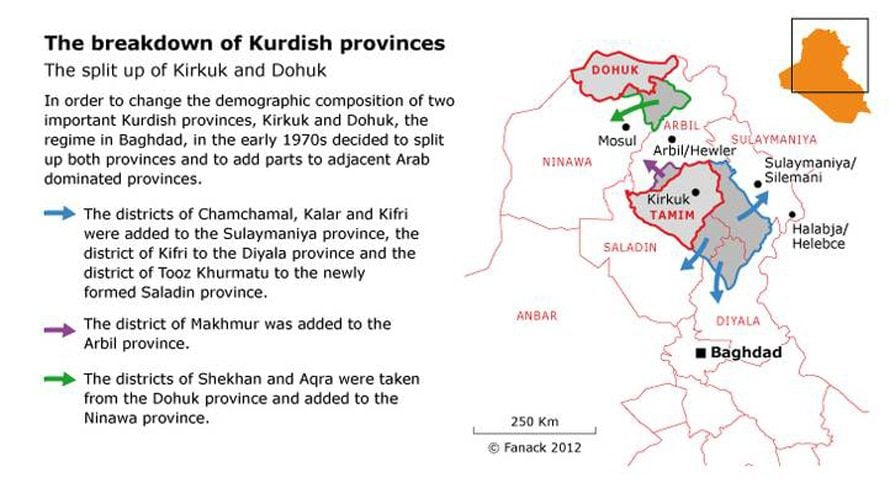

The boundaries of the province were redrawn, after the collapse of one of the major Kurdish uprisings in 1975, and it lost a third of its territory and a third of its Kurdish inhabitants. The remnant of the province was renamed al-Tamim (literally, ‘Nationalization’, a reference to the successful nationalization of the Iraqi oil industry, three years earlier). Many thousands of Kurds (as well as Turkmen and Assyrians) were robbed of their possessions and deported to other parts of Iraq. In the 1988 Anfal counter-insurgency campaign, Iraqi forces especially targeted Kurdish villages north and the east of Kirkuk, killing thousands.

After the downfall of the regime of Saddam Hussein, Kurds succeeded in perpetuating a de facto self-government that had existed since 1991. The Kurdish Region was officially limited to the three northern provinces Dohuk, Arbil, and Sulaymaniya, although parts of the neighbouring provinces, inhabited mainly by Kurds, also came under the direct control of the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG). Kurds wanted those parts of the country to be added to a Kurdish Region in the federal state of Iraq. In Article 140 of the new Constitution a procedure was laid down to resolve this issue: 1) return of the deportees (Kurds and others) and restitution of stolen property, 2) a census to determine who will be authorized to vote in, 3) a referendum on the status of Kirkuk, in which the voters will indicate whether the area they inhabit should become part of the Kurdish Region. Financial compensation was offered to Arab settlers who were willing to leave Kirkuk and return to their presumed places of origin. The referendum was scheduled to take place on 15 November 2007, but Baghdad and Arbil were unable to resolve their disagreements; ‘technical reasons’ were mentioned. Several later dates would pass, to no effect. It appeared to be a lack of political will in Baghdad to deal with the issue in what they considered the agreed way, in an effort to limit the power of the KRG and to leave the central government in control of oil revenues. For the Kurds this situation was hard to accept, and it has become a growing source of tension with the Arabs, Kirkuk’s Turkmen population, and others.

A worrying sign was a steady increase in violence, not only in the province of Kirkuk, but also in other areas, such as the city of Mosul. On one occasion, in September 2008 in Khanaqin, in the province of Diyala, armed forces of the Kurds and those of the central government were on the brink of a violent confrontation, after government forces tried to take over certain facilities in the Khanaqin mixed-population sub-districts, which had been in the hands of Kurdish forces since 2003. With US mediation, however, the crisis was quickly defused.

Kurdish Takeover

The standoff between the Kurdish demand to incorporate Kirkuk and Baghdad’s resistance to that demand continued for the next few years. In 2014, however, Kurdish authorities profited from the flight by the Iraqi army in the face of advancing units of jihadist Islamic State in Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS) to take Kirkuk. On 12 June, the last Iraqi army troops left Kirkuk, and thousands of Kurdish Peshmerga forces took control of the city. They also took over, on the basis of a pre-1975 map, large parts of the provinces of Kirkuk, Diyala, Niniveh, and Salahuddin, which had long been contested territories. President Masoud Barzani of the Kurdish autonomous region promised to do everything necessary to keep these areas under the control of his Kurdish Regional Government. He stressed repeatedly that there was no going back to Iraqi rule and that article 140 was dead. Under the circumstances, Baghdad was impotent to react.

Although the Kurdish government made Kirkuk more secure after the takeover, tensions persisted. The city remained the target of suicide attacks by ISIS, which had, in the meantime, renamed itself Islamic State (IS) and announced the birth of a caliphate in areas in Iraq and Syria that it had conquered. On 23 August, for instance, 31 people were killed when three bombs were detonated in a busy district of Kirkuk.

Moreover, the international human-rights organization Amnesty International reported in the first week of September growing sectarian tensions between the main ethnic and religious groups—that is, Kurds, Turkmens, and Shiite and Sunni Arabs—resulting in summary executions in the city. Turkmens and Shiite and Sunni Arabs have not acquiesced to the Kurdish takeover. Amnesty International reported that divisions and distrust have grown, as a result of the fear of the growing threat posed by IS. “Accusations such as ‘the Sunnis [Turkmen and Arabs] are cooperating with IS’ and ‘the Shiʿa [Turkmen] and the Kurds are cooperating with Iran-backed Shiʿa militias’ are common,” according to Amnesty’s report.

In the meantime, Kirkuk’s crude-oil output has diminished by 90 percent since June, from 300,000 barrels a day to 30,000, compared to the same period in 2013, press agency Reuters reported. The Baji refinery, the largest in Kirkuk, has been closed because of damage incurred during fighting between Kurdish fighters and IS jihadists. Other oil installations have also been damaged in the fighting.