Introduction

Saudi Arabia is an absolute monarchy, with a Basic Law, but no political parties, unions, or other types of political association. The country’s basic system of governance – an alternative to a constitution – was established in 1992, following numerous calls for political reform. The Basic Law of Governance consists of 83 articles, all generated by a special committee organized by the King and the Minister of Interior at the time. The articles are based on Sharia (Islamic law). The law names the Koran, the Muslim holy book, and the Sunnah, the Prophet’s teachings and deeds, as the basic source of governance.

There is no real division between the powers of the three government branches – the Legislative, the Executive, and the Judicial.

The Monarchy

The King is the head of state, the Prime Minister, and the Supreme Commander. He combines legislative, executive, and judicial functions. Royal decrees have the power to overrule any judicial or administrative decision. While the three authorities in the country are recognized as judicial, executive, and regulatory, the King is the ultimate arbiter for these authorities, based on Article 44 of the Basic Law of Governance.

The royal family dominates the government, and most of the key positions in the country are occupied by members of the family. The authoritarian nature of the government limits all associations strictly without official license or supervision.

Besides the King, who holds vast powers, a few influential members of the royal family and the higher council of religious scholars share in shaping political decisions. Religious scholars maintain a strong grip on internal affairs.

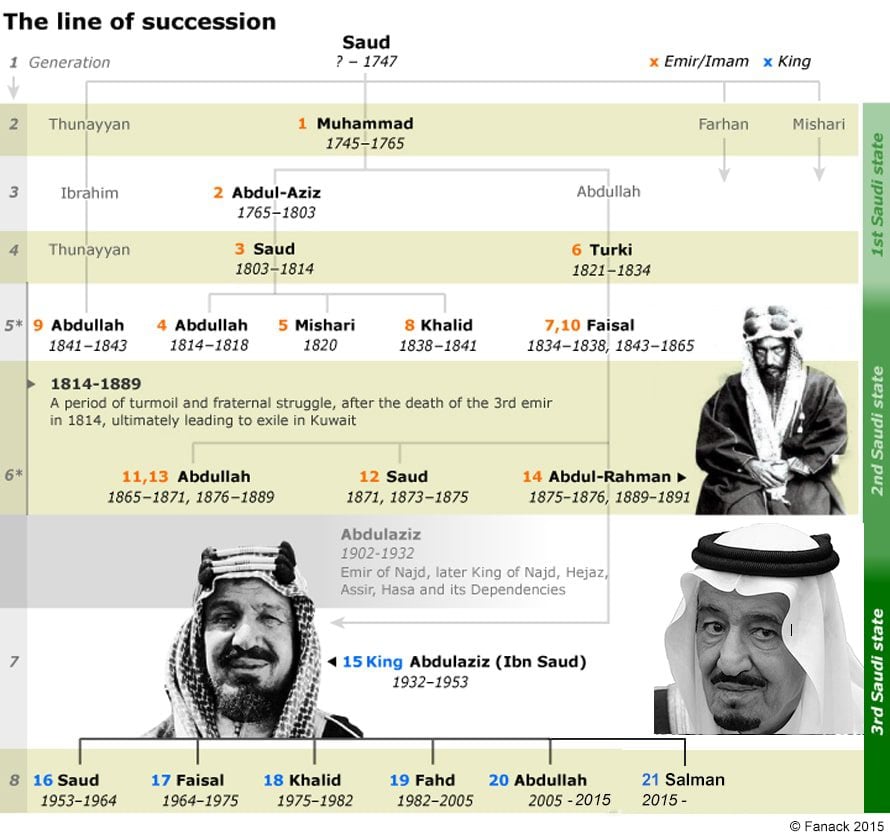

According to Article 5 of the Basic Law of Governance, rulers of Saudi Arabia will be chosen from amongst the sons of the founder, Ibn Saud (King Abdulaziz), and their descendants. The order of succession to the throne follows agnatic seniority. Since 2006, the Allegiance Council (Hayat al-Baya), consisting of the surviving sons of founder King Ibn Saud, his grandsons whose fathers are deceased, incapacitated, or unwilling to assume the throne, and the sons of the king, decide on the succession to the throne. The King carries the title of the Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques (Khadim al-Haramain al-Sharifain) in Mecca and Medina, which emphasizes the status of Saudi Arabia in the Islamic world.

The House of Saud

The first Saudi state was established in 1744, when Muhammad ibn Saud (died 1765), emir of the oasis of Diriya in Najd (in the centre of the peninsula) made a pact with a religious reformer of that period, Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab (died 1792). The union aimed to create an Islamic realm ruled by a strict interpretation of Islam, frequently referred to as Wahhabism.

The first Saudi state collapsed in 1818 under attacks from the Ottoman Empire, provoked by the ongoing Al Saud / al-Wahhab expansion into territory under Ottoman control (Diriya was erased and never rebuilt). However, the pact between the religious figures and the Al Saud remained in effect.

Within six years (in 1824), the second Saudi state was established. In the end (in 1891), this state collapsed following serious internal strife among Al Saud emirs and pressure by the Ottomans and neighboring rival emirs, ultimately leading to the exile of the Al Saud emir in Kuwait.

The third Saudi state was established in 1932, after a period of thirty years of territorial conquest by Abdulaziz Al Saud (Ibn Saud; 1876-1953), with the support of Great Britain, so long as its own interests in the coastal areas in the Persian Gulf, in Oman and Yemen, were served.

Abdullah bin Abdulaziz Al Saud (born 1924) ascended the throne in 2005 as the sixth King of Saudi Arabia. After his death on 23 January 2015, he was succeeded by his half-brother Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud (born 31 December 1935).

The Executive

In theory, the Council of Ministers acts as the official executive branch of the government. In practice, all ministers are appointed and dismissed by royal decree. The ministers are appointed every four years and include many members of the royal family. Currently there are 22 government ministers.

The Royal Court (al-Diwan al-Maliki) is the King’s office under which important legislative matters submitted or initiated by royal decrees are negotiated. The key people affecting legislation are influential members of the royal family, ministers, some advisors, and members of the higher council of religious scholars. Tribal leaders, too, can be influential in the highest levels of decision-making. Also, citizens can appeal to the royal court regarding matters in which they need the King’s assistance, for instance, to overcome bureaucratic problems.

The late King Fahd bin Abdulaziz enacted the Law of the Council of Ministers in 1992. The law identifies the Council of Ministers as the regulatory authority and the King as the Prime Minister. The law consists of nine chapters and 83 articles. Royal decrees appoint ministers, accept resignations, and relieve ministers and deputy ministers of their duties. The duties of the ministers are stipulated in Articles 57 and 58 of the Basic Law of Governance. Resolutions of the proceedings of the Council of Ministers become final after the King’s approval. Ministers continue in their posts for four years or until relieved by the King.

Article 24 of the Law of the Council of Ministers identifies the Council as the ultimate executive authority, with full jurisdiction over all executive and management matters, including monitoring the implementation of regulations, by-laws, and resolutions; creating and organizing public institutions; following up on the implementation of the general development plan, and forming committees for the oversight of ministers and governmental agencies’ conduct of business.

The Legislative

The unicameral legislature is called the Majlis al-Shura (consultative council), which has 150 members and a chairman, all appointed by the monarch for four-year terms, half of whom at least have to be new members.

The Majlis al-Shura passed through several stages before its current structure was established. The founder, King Ibn Saud, called for creating the Majlis when he entered Mecca in 1924. Modestly structured, the Majlis al-Shura has been formed over the years under a Basic Law with a small number of advisors not exceeding twelve.

The founding of the Council of Ministers in 1953 distributed the functions of the old Majlis al-Shura across various ministries and administrations. Ultimately, the council was left with limited power and efficacy until King Fahd bin Abdulaziz promulgated the Basic Law of the Majlis al-Shura in 1992.

The law describes in 30 articles the basic functions of the council committees and the rules for floor debates. The King has the power to restructure and dissolve the Majlis as he deems appropriate. Initially, the Majlis al-Shura had 60 members and a speaker, and it was gradually enlarged to 120 members and now to 150 members chosen by the King.

There are twelve committees in the Majlis al-Shura/Majlis, which deal with human rights, education, culture, information, health, and social affairs, services and public utilities, foreign affairs, security, administration, Islamic affairs, economy and industry, and finance.

Twelve women members serve as part-time advisors in the current council, but, in 2011, King Abdullah allowed women to be appointed full members in the next term, in 2013.

The primary function of the Majlis al-Shura is to advise the King on policy matters, whether domestic or international and on treaties. Discussion of policies can be initiated in the council in response to a royal order or a call from members or citizens.

A council resolution is made official by a majority and is then forwarded to the Prime Minister (the King or his deputy) for consideration by the Council of Ministers. If both councils (the Advisory Council and the Council of Ministers) agree on a decision, the resolution will be sent to the King for his approval. In the event of a disagreement, the King decides what is appropriate.

It takes at least ten members of the Majlis al-Shura to propose a law, a policy, or a draft amendment. Laws, international treaties and agreements, and concessions are studied by the Majlis, promulgated and amended by royal decree, and published in the Official Gazette (al-Jarida al-rasmiya) before they take effect.

The Judicial

The judicial system in Saudi Arabia is based on Sharia (Islamic law). Article 46 of the Basic Law of Governance identifies the judiciary as an independent authority. The decisions of the judges are not subject to any authority other than Islamic jurisdiction. In reality, however, the King has the power to intervene and affect any judicial proceedings through royal decrees.

The Supreme Council of Justice represents the judiciary branch of the government. It consists of twelve judges, all of whom are appointed by the King, according to recommendations from the council members. The King acts as the last resort of appeal and has the power to pardon. The Supreme Council is empowered to appoint, promote, and transfer judges.

The Saudi court system consists of four levels of courts. The most numerous and most basic are the Sharia Courts, which hear most cases in the legal system. At the second level are the General Courts, ruling on criminal cases, tort actions, personal and family law matters, and real estate. At the third level, civil claims are often filed with the governorates’ offices to solve disputes via arbitration. If this fails, then the cases are filed with the courts.

The Court of Appeal is the fourth and final level of courts. Three or more judges settle, by majority decision, submitted disputes. The Board of Grievances hears cases involving the government. The third branch of the legal system comprises the various committees within the government ministries and Chambers of Commerce, which rule on specific legal disputes such as labor issues.

Local Government

Saudi Arabia is divided into thirteen provinces, each further divided into governorates, which, in turn, are divided into municipalities. The thirteen provinces are Mecca (Makka), Riyadh, the Eastern Province (al-Mintaqah al-Sharqiya or al-Sharqiya), Asir, Medina (al-Madina), Jazan, al-Qassim, Tabuk, Hail, Najran, al-Jawf, al-Baha, and the Northern Borders Province (Mintaqat al-Hudud al-Shamaliya).

A royal decree in 1992 enacted the Law of the Provinces. Each province is administered by a governor and a deputy, who is appointed by royal decree upon the recommendation of the Interior Minister. Most of the governors and their deputies are members of the royal family. The governor is accountable to the Interior Minister. The governor and his deputy are tasked with the administrative affairs of their respective governorate, according to Article 7 of the Law of the Provinces. Most provincial offices are open to the public periodically when members of the local community can submit their requests and appeals to the governor to review or intervene.

In 2005, local elections in 178 municipalities were held for half of the seats in the municipal council. Only male citizens over 21 years of age were allowed to vote and stand for election. In 2011, King Abdullah announced that women would be allowed to stand and vote in the next municipal elections in 2015. The administration of all municipal governance is under the Ministry of Municipal and Rural Affairs.

Political Parties

Political parties have not been permitted to function in Saudi Arabia since the beginning of the monarchy. Several petitions for reforms have included the request that the state allows political associations and parties to no avail. Some notable groups work without a legal umbrella, such as the Umma Islamic Party and the Civil and Political Rights Association, both of which are being monitored and harassed by the authorities. Their leaders were banned from travel, prosecuted, or imprisoned, having been charged with ‘disobeying the Wali al-amr,’ that is, disobedience of the King.

The Saudi Military

The huge amount of money Saudi Arabia spends on its military means the country has one of the best-equipped armed forces in the region. Its involvement in Yemen’s civil war leading an international coalition has given its forces valuable frontline experience. However, its failure to defeat the Houthi rebels has also raised questions about how effective a fighting force the Saudi military actually is.

In 2019, Saudi Arabia ranked 25 out of 137 countries included in the annual GFP review. That year, the number of people who reached military age was estimated at 583,161 personnel, while military expenditure was estimated at $70 billion. According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, in 2018, military expenditure accounted for 8.8 percent of GDP compared with 10.3 percent in 2017 and 9.9 percent in 2016.

The Saudi army engaged in aerial combat for the first time during the First Gulf War (1991), when a Saudi pilot flying a McDonnell Douglas F-155 Eagle detected and shot down two Iraqi Dassault Mirage planes, which had crossed into Saudi territory, using the American-manufactured Airborne Warning and Control System (AWACS).

To those who witnessed the event, the Saudis’ advanced technological military capabilities and their ability to fight within coalitions were clear. However, it also showed the country’s reliance on foreign military support, which started long before 1991 and continues to this day.

The first larger ‘international’ conflict in which the Saudi armed forces were involved was the struggle between Yemeni government forces and Houthi rebels in 2009; it reportedly included small incursions by ground troops and aerial attacks by F-15 fighter-bombers. Reports suggested that the Saudi ground troops met heavy resistance from Houthis, which led to substantial, though unconfirmed, Saudi losses.

Saudi troops entered Bahrain in 2011, under the aegis of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), along with forces from the United Arab Emirates, to prop up the rule of King Hamad against a mainly Shiite campaign for democratization; the Saudis remain there to this day.

In 2014, Saudi Arabia committed modest air forces to the coalition air campaign against the extremist Islamic State in Iraq and Syria that began in 2014.

In March 2015, Saudi Arabia, heading a coalition of several Arab states, launched a campaign of airstrikes against Shiite Houthi rebels. It allied troops of former Yemeni president Ali Abdullah Saleh intending to bring back the regime of President Abd Rabbuh Mansour Hadi to Sanaa.

In the face of the Saleh-supported Houthi offensive, Hadi fled the country for safety in Saudi Arabia and requested international help to restore his government.

The Saudi government accused Iran of supporting the rebels to spread its influence in the Arab Peninsula. However, after three months of bombardments, the Saudi leadership has not reached its targets.

| Index | Number | Rank out of 137 |

| Total military personnel | 230,000 | - |

| Active personnel | 230,000 | - |

| Reserve personnel | 0 | - |

| Total aircraft strength | 848 | 12 |

| Fighter aircraft | 244 | 12 |

| Attack aircraft | 325 | 9 |

| Transport aircraft | 49 | 16 |

| Total helicopter strength | 254 | 18 |

| Flight trainers | 207 | 12 |

| Combat tanks | 1,062 | 24 |

| Armoured fighting vehicles | 11,100 | 4 |

| Rocket projectors | 122 | 29 |

| Total naval assets | 55 | - |

| Frigates | 7 | - |

Saudi Arabia’s military strength in 2019. Source: GFP review.

Oil revenues have always permitted the Saudi government to equip the armed forces with advanced, expensive weaponry, be it aircraft, naval vessels or main battle tanks. However, as all this equipment has to be incorporated into units and personnel has to be trained, foreign militaries that already use the equipment and support personnel of the related arms industry have to work closely with the Saudi government. There are also continual rumors of corruption surrounding the massive arms deals and related deals with contractors.

Like other Arab armed forces, especially those of the GCC, the recruitment of technologically sophisticated personnel is difficult because of shortcomings in the country’s educational system. According to analysts of the Washington, D.C.-based think tank, the Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), the demographic base is apparently too small to sustain the large armed forces.

According to CSIS, the Saudi regular armed forces total some 125,000 men, plus 100,000 in the Saudi Arabian National Guard. Paramilitary forces are estimated to have another 130,000 men in uniform: 30,000 in the Border Guard, 20,000 in the Drug Enforcement Agency, 25,000 in the Civil Defence Administration, 30,000 in the Special Emergency Forces, 10,000 in the Petroleum Installation Security Force, and some 10,000 in the Special Security Forces.

These figures do not add up to cumulative military power because organizations and units are specially tasked to keep an eye on each other to safeguard the status quo of the Kingdom.

The American military presence was reduced before 2003, first under the pressure of Bin Laden’s al-Qaeda and later because the Saudi government did not want to be involved in the invasion of Iraq. Nevertheless, American support elements, such as tankers, radar planes, and intelligence assets, still use the country’s extensive facilities. In 2013 it was revealed that US armed drones were stationed in the south of the country, presumably for surveillance and attack missions over Yemen, against al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP).

Royal Saudi Army and National Guard

Given the opaque nature of Saudi governance, it is difficult to obtain exact figures on the size of the Saudi armed forces. The Saudi army is estimated to have about 100,000 active service personnel. Its main equipment includes an estimated 1,000 tanks, including the late-version General Dynamics Land Systems Abrams M1A2. At the beginning of this decade, there was talk of a pending deal with the German government to purchase some 270 Krauss-Maffei-Wegmann (KMW) Leopard 2 tanks.

Germany suspended this deal after Riyadh executed 47 prisoners, including a respected Shiite cleric, in early 2016. However, Saudi Arabia showed interest in the acquisition of Pakistani Al-Khalid tanks, trials of which have already been conducted. There are estimated to be more than 3,000 armored personnel carriers.

The Saudi Arabian National Guard (SANG) is seen as a “Praetorian Guard,” consisting of well-paid and well-trained troops, forged out of tribes loyal to the monarchy, the Al Saud family. The SANG is tasked with the direct protection of the royal family and the country’s vital support systems, such as the oil infrastructure and the main religious sites. Its size can measure its relative importance: with an estimated 100,000 personnel, it is as large as the regular armed forces and is equipped with thousands of armored vehicles.

Royal Saudi Navy

The navy has an estimated 17,000 men, including some 4,000 marines. Although organizationally divided into western and eastern fleets, in the Red Sea and the Arabian Gulf, the Saudi naval forces seem especially positioned and projected against Iran’s.

The major surface vessels consist of three French-built al-Riyadh frigates, versions of La Fayette-class vessels, four French-built Medinah-class frigates, four US-manufactured Badr-class corvettes, and dozens of smaller patrol boats.

In December 2014, the US government notably approved the sale of Mark 41 (MK 41) vertical missile launchers, a system with which no vessel in Saudi service is currently compatible, triggering rumors that a contract for a new class of large-surface combatant vessels will soon see the light.

The large Iranian force of three Kilo-class medium-size and dozens of Iranian-built midget submarines is regularly cited as stirring Saudi interest in acquiring its own underwater capability. Dutch, German, and French submarine yards have in the past also been mentioned as potential providers of these costly systems. No concrete steps have so far been reported.

Royal Saudi Air Force

The Saudi air force has about 20,000 men in uniform – not to count an estimated 16,000 men in the separately organized Air Defence Force, with the latest model of Patriot missiles. The air force draws its inventory mainly from the United States and the United Kingdom. With more than 200 Boeing F-15s in interception and ground attack roles, the Saudi air force is the third-largest user of these planes, after the US and Japanese air forces. In the al-Yamamah and al-Salam programs, the UK sold the Kingdom some 80 Panavia Tornado bombers and 27 Eurofighter Typhoon fighter-bombers.

The support aircraft, including tankers and radar planes, match the cutting-edge quality of the fighters and bombers. But there is also criticism. CSIS concluded that the air force in the 1990s developed significant gaps that it is now struggling to plug. In a lengthy analysis, the think tank reported that “a lack of overall readiness, and poor aircrew and maintenance to aircraft ratios, severely reduced the effectiveness of its F-15s and Tornados”. Monthly training hours, CSIS continued, “for the F-15, dropped to 6 hours. They have since risen back to 9, but need to be 12-18. Long-range mission and refueling training also dropped sharply, but is slowly being brought up to standard”.

Supposedly, there was also a “failure to develop effective joint warfare capabilities, realistic joint warfare training capabilities, and transform joint warfare doctrine into fully effective war-fighting plans to support the land-based Air Defence Force, and the Army, National Guard, and Navy.”

This neatly illustrates that money will accomplish only so much.

Saudi Strategic Missile Force

The secrecy surrounding the Saudi missile force stationed in the south of the country has been gradually lifted. For example, commercially available satellite imagery contributed to revealing that the country had bought in the 1980s Chinese conventional Dong Feng-3 missiles with an estimated range of 2,500 km with a 2,000 kg warhead; these are reported to suffer from poor accuracy. The missiles are meant as means of retaliation in case of escalating conflict with Iran or Israel.

In April 2014, one of the missile launchers, of which a few dozen are estimated to be operational, was publicly paraded. Photos of them appeared on a Saudi military web forum. Images of models of the DF3 and personnel of missile units also surfaced on social media. In 2007 another sale of Chinese missiles, in this case, the more accurate DF-21 was reported.

The Saudi-American deal

A week before American President Donald Trump made his first foreign trip to the Middle East in May 2017. The United States announced an arms deal with Saudi Arabia worth $110 billion. The White House described the deal as a long-term enhancement for Saudi and GCC security against the Iranian threats. The package included four frigates, the Terminal High Altitude Air Defence (THAAD) system, 150 Black Hawk helicopters, and precision-guided bombs. A month later, several American media described the deal as ‘fake news.’ According to the Brookings Institute, ‘there are many letters of interest or intent, but not contracts … None of the deals identified so far are new. All began in the Obama administration.’

Corruption

Corruption in Saudi Arabia has always been worst at the highest levels of the government. Still, long-term observers generally agree that corruption has trickled down during the last twenty years due to the slowly rising cost of living and stagnating wages. Administrative corruption is still less widespread than in poorer Arab countries, such as Egypt and Syria.

There is no real public accountability for bureaucrats, as there are no disclosure rules. The Majlis al-Shura is reluctant to deal with specific cases of misconduct, and the press is, with notable exceptions, generally tame. There are intra-bureaucratic integrity mechanisms in Saudi Arabia, such as an administrative supervision agency and a disciplinary board for bureaucrats, but these are generally ineffective.

More important is the personality of the various ministers, which can have a significant impact on the level of corruption in their institutions – although even a reportedly hard-hitting reformer like Labour Minister Ghazi al-Gosaibi has been unable to clean up the large-scale influence-peddling in his ministry. In practice, the King is not able to supervise effectively the activities of his older brothers in their respective ministries.

Latest Articles

Below are the latest articles by acclaimed journalists and academics concerning the topic ‘Politics’ and ‘Saudi Arabia’. These articles are posted in this country file or elsewhere on our website: