Introduction

With the spectacular growth of the oil sector, Saudi Arabian society experienced sweeping changes after World War II. The outward manifestation thereof is impressive yet misleading. In many ways, Saudi society has remained starkly conservative. The religious establishment, traditionally closely aligned to the Al Saud, ensures that this remains the status quo.

Family, Clan, and Tribe

Marriage in Saudi is usually arranged in accordance with tradition. Intermarriage is usually between members of the same line of descent; tribal and immigrant families rarely intermarry. The family follows a strict patriarchal structure, in which the father is the head of the family, and the mother’s main task is to run the household and look after the husband and children. Education and employment have given women more power outside the home and as a partner in the financial maintenance of the family.

Urbanization and education have reduced the effect of tribal culture and values. While many Saudis still live with their extended family in the same household, nuclear families are on the rise, and there is less adherence to traditional tribal values.

Tribal values include care for the elderly and generosity towards relatives and guests. In turn, this becomes social capital for the Saudi individual, whose first line of support is the immediate family or tribal leaders. Tribal leaders still negotiate major problems with the clan members and intervene with the authorities on behalf of their members.

Women

Saudi women make up about 49 percent of the total population. They live in patriarchal and male-centered societies. Traditionally, women have held an inferior position in Saudi society, restricted to the home and marital duties. Education and access to employment opportunities for women have helped some women to secure their financial independence while gaining a higher status in their communities.

Youth

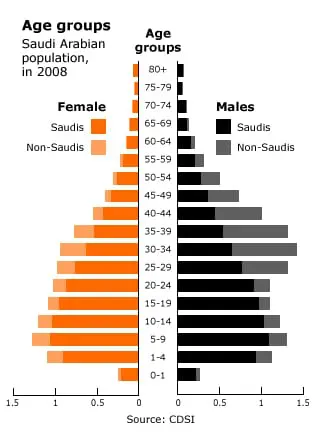

Saudi youth represent the largest demographic group in Saudi Arabia, with more than 37 percent of the total population below the age of fourteen, 51 percent below the age of 25, and two-thirds below the age of 29. This is typical of Gulf Cooperation Council demographics, where youth constitute approximately 61 percent of the population.

In reaction, the government launched reforms throughout the 2000s in science and technology education to meet the demands for the job market. The Saudi curricula are generally dominated by religious education, and the reform plans aim to create more diversified, knowledge-based education to meet the demands of the economy.

The financial costs of starting a family are high for young Saudis. Many Saudis rely on help from their families or clans to finance a wedding but fall short when maintaining an adequate income.

Education

In 2012, Saudi Arabia’s public education system included 24 universities and some 25,000 schools, as well as many colleges and other institutions. The system is open to all citizens and provides students with free education, books, and health services.

While the study of Islam remains at its core, the modern Saudi educational system also provides instruction in the arts and sciences. The Ministry of Education sets overall standards and oversees special education for the disabled. They also decide which textbooks are allowed. The Saudi Ministry of Education has banned several books from school libraries, including Sayyid Qutb, an Egyptian writer who was the leading intellectual of the Muslim Brotherhood in the 1950s and 1960s. This has been justified as part of the country’s effort to prevent youths from joining radical Islamist networks.

The school enrolment rate for girls increased from 90.5 percent in 2005 to 96.1 percent in 2010. Between 2001 and 2010, boys’ net primary enrolment rate at the primary education level increased from 84 percent to 96.7 percent, compared to an increase from 82 percent to 96.5 percent for girls. The ratio of girls to boys in all educational levels has increased from 0.851 in 1990 to 0.991 in 2010.

The overall literacy rate (counting persons over fifteen years of age who can read and write) was 86.6 percent in 2010 (90.4 percent for males, 81.3 percent for females). General education in the kingdom consists of kindergarten, six years of primary school, and three years of intermediate and high school. Students can choose to attend a high school with commerce, the arts, and sciences or vocational training after elementary and intermediate school. In high school, students take comprehensive exams twice a year, under the supervision of the Ministry of Education.

Saudi students can now obtain degrees in almost any field in the kingdom. The five major universities in the kingdom are King Saud (the oldest university in the country), King Abdulaziz (the largest, with over 42,000 students), King Faisal, Imam Muhammad ibn Saud Islamic University, and Umm al-Qura.

The General Organization operates most of the kingdom’s vocational training centers and higher institutes of technical education for Technical Education and Vocational Training (GOTEVOT) and the Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs. The Ministry of Education runs vocational secondary schools, and several other government agencies operate institutes or training centers in their particular specialties. There are also several private training centers meeting the needs of the employment market.

The kingdom established many adult education centers to make education available to a broader group and eliminate illiteracy. For people living in isolated rural areas, the government conducts intensive three-month adult-education courses during the summer.

The kingdom has established several educational institutions throughout the world for Saudi students living abroad. The three largest such institutions are located in the United States, Great Britain, and Germany.

Teaching is still oriented toward rote learning, and Arabic and Islamic studies have a dominant position in the curricula. Teaching reform has been discussed for several years, but results on the ground are still limited, as teachers’ qualification remains an issue. The number of private schools has grown, and more than a dozen private universities have recently been licensed. Access to quality education for the less affluent, however, remains a problem.

As in other Arab countries, research and development spending in Saudi Arabia is still meager; ARAMCO and state heavy-industry giant SABIC are the only entities engaging in significant research. Except for the small King Fahd University of Petroleum and Minerals, public universities are of low quality. Awareness of all these issues has risen significantly, however.

Urbanization

Over the past few decades, one striking effect of Saudi development has been rapid urban migration. In the early 1970s, an estimated 26 percent of the population lived in urban centers. In 1990 that figure rose to 73 percent. The capital, Riyadh, had about 666,000 inhabitants, according to the 1974 census, and 4.7 million in 2010. In mid-2012, the total population of Saudi Arabia was estimated to be just under 29 million.

Urbanization, education, and modernization have had profound effects on society as a whole, especially on the family. The urban environment fostered new institutions, such as women’s charitable societies, that facilitated women outside the family network. Urban migration and wealth have broken up the extended family household as young couples leave their hometowns and establish themselves in single-family homes.

Civil Society

There were Gulf regional traditions of civil society in Saudi Arabia before the arrival of large-scale oil income. Since then, the state has taken over many welfare functions and has generally prevented independent social organization. Although there are numerous welfare societies with considerable resources, these still exist in the shadow of the state and are tightly controlled by it.

In the aftermath of the terrorism threat of 2003-2004, the state increased its control over religious organizations. There are no powerful independent unions, syndicates, or issue groups in the kingdom, leaving Saudi society fragmented. The only social structures most Saudis can rely on are small-scale, informal networks of kinship and friendship. Recent government attempts to set up formal interest groups in a top-down fashion have largely failed to gain public participation.

However, in recent years, some powerful civil society groups have appeared. These groups worked mostly online to access a relatively free space of speech and assembly. There are three types of civil society organizations working outside the government umbrella. The first type works non-politically, supporting the state while promoting a new partnership and dialogue to empower civil society. The second type is semi-political, working within the government to promote a change of policies and the direction of the political system. The third type is political, working in direct opposition to the state. Most of these organizations promote a pluralistic and human-rights approach to citizenship.

Several governmental organizations act to promote civil society. The Council of Saudi Chambers of Commerce and Industry acts as a bridge between citizens and the state. Two governmental human-rights organizations work to document and report violations of formal regulations and human rights, reporting directly to the royal court.

Crime

Incidents of crime in Saudi Arabia remain at a low level. Although the Saudi government does not provide crime data, non-violent street crime (petty theft and pick-pocketing) has increased in recent years.

As the head of the monarchy, the King appoints members of two advisory councils which, in conjunction with royal decrees issued by the King, enact and oversee the country’s Islam-based laws and conservative customs and social practices.

Saudi authorities do not permit criticism of Islam or the royal family, and the government prohibits the public practice of religions other than Islam. Non-Muslims suspected of violating these restrictions have been jailed.

Islamic law is the basis for Saudi law, which is strictly enforced by the police. Persons violating Saudi Arabia’s laws, even unknowingly, will be arrested, imprisoned (expelled in the case of non-nationals), or even executed. Suspects can be detained for months without being charged or afforded legal counsel, pending a final disposition of a criminal case. Penalties for the import, manufacture, possession, and consumption of alcohol or illegal drugs are severe, and convicted offenders can expect jail sentences, fines, public flogging, and/or deportation. The penalty for drug trafficking in Saudi Arabia is death, and Saudi officials make no exceptions. Customs inspections at ports of entry are thorough in finding drug and alcohol violators.

Latest Articles

Below are the latest articles by acclaimed journalists and academics concerning the topic ‘Society’ and ‘Saudi Arabia’. These articles are posted in this country file or elsewhere on our website: