The Moroccan parliamentary commission for teaching, culture, and communication recently approved a new law that creates a major shift in education policy in the country. The new legal framework will not only enable technical subjects at school to be taught in foreign languages but it will also require the Berber language Tamazight to be taught to all Moroccan students. This announcement followed another major development for Tamazight speakers: in June 2019, lawmakers unanimously approved a bill confirming the language’s official status, alongside Arabic.

However, the vote came eight years after the language was recognised within a new constitution in the North African country, and that preliminary recognition only came after decades of advocacy.

Tamazight is the language spoken by the Amazigh or Berber population. According to a 2004 census, there are eight million people in Morocco who speak one of the three main Berber dialects each day and it is estimated that there are 25 to 30 million speakers of Berber dialects hin North Africa.

Historically, the institutionalization of the language has seen push back from official recognition, although it is spoken by a substantial number of people in the Kingdom.

In fact, for many years, giving children Amazigh names was forbidden in Morocco, and administrators would often refuse to enter these names into the civil registries. The effect of such a ban was the exclusion of those who speak the language – usually people from poor, rural areas of the country – from participation in various aspects of public life. Other reasons for opposing the inclusion of the Berber language include that it is better not to add to the already complicated language mix in schools, while others are committed to Morocco’s Arabization.

Nowadays, the inclusion of the language rallies much more political and societal acceptance, although the journey has not been simple. Following a history of resistance and the cultural movement of the Amazigh for acceptance within Moroccan state-recognised identity throughout the 20th century, in 1994 King Hassan II supported the teaching of Tamazight in schools and the High Commission of Amazighité was created to oversee this process.

For the first time in its history, the country’s revised constitution of 1996 recognised Amazighit culture as a “fundamental component of its identity,” according to Paul A. Silverstein in his chapter on the movement in the Oxford University Press book ‘Social Currents in North Africa.’

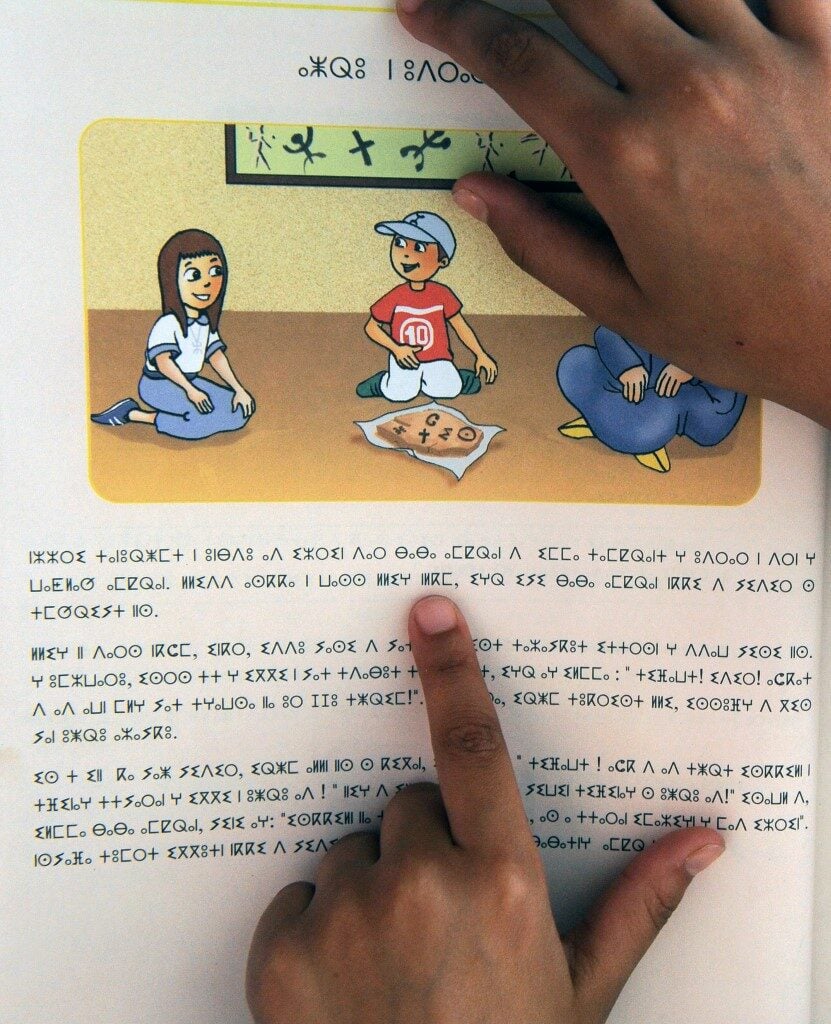

Further moves towards acting upon this recognition occurred in 2001, when King Mohammed VI formed the Institut Royal de la Culture Amazighe (Royal institute of Amazight culture) by royal decree, raising awareness of Amazigh society in Morocco and continuing to standardise the language with a particular Tifinagh alphabet, working to integrate the language into schools and the media.

In 2011, aided by the Arab Spring, Amazigh and Islamists worked in tandem to call for increased freedom in Morocco, which eventually led to a new constitution being adopted in 2011. It recognized Tamazigh as an official language in the country. While Tamazight had started to be taught in schools, it is only now, in 2019, that legislation has been introduced.

Part of the reason why that discourse has taken so long to be put into practice is that there is a recognition by political leaders that this is a very complex issue with serious social and political ramifications, Amine Ghoulidi, a researcher at King’s College London, told Fanack Chronicle.

“Language is a fundamental component of identity and needs to be managed with care. Recognition of the [Amazighi] language would need to go beyond cosmetic manifestations such as street signs and book covers,” Ghoulidisaid.

All the while, activists and supporters of official recognition of Tamazight have kept up the pressure. However, language is not the only domain where Amazigh identity is yearning for inclusion.

Other struggles have included the recognition of the Amazigh New Year, an event called Yennayer, as a national holiday each year on January 12. Algeria made it a national holiday last year, and the activists would like Morocco to do the same.

A recent online petition to Google to integrate the Tamazight language into Google Translate was also acknowledged by the internet behemoth in March.

However, in other parts of the world, such as Algeria, Amazigh people are still struggling for equal stature. In July 2019, the Algerian authorities cracked down on protesters carrying the Amazigh flag at demonstrations.

The new law will “operationalise the official status of Amazigh (…) preserving the language and protecting cultural heritage”, according to the Moroccan Culture Minister Mohamed Laaraj, who spoke after the June vote.

While some have been critical the law still has holes, for instance insisting that the language be used by schools or the media, the new framework law for Tamazight might be seen as a step in the right direction to filling them. The aim of the framework for education is to increase access to education in Morocco.

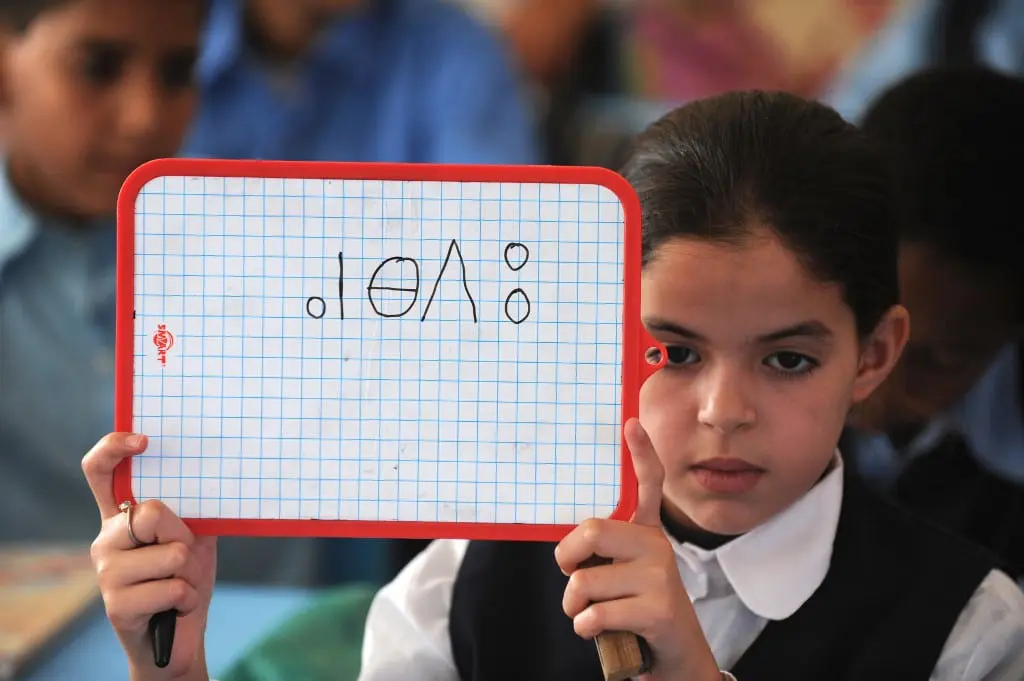

Already, according to Morocco’s Head of Government, Saad Eddine El Othmani, figures from 2018 show that the number of students in primary schools learning Tamazight has increased from 500,000 the previous year to 600,000 students across 4,200 primary schools. A better focus on teaching the language could help limit the number of children who fail school because their first language is Tamazight rather than Arabic. Integration of the Tamazight language has also been argued to help integrate native speakers into learning more internationally recognised languages such as French, English and Arabic. Although, at the heart of the issue, is a matter of social inclusion. Institutionalisation should in theory lead to parity in Moroccan society.

However Paul A. Silverstein, who is a Professor of Anthropology at Reed College, Oregon in the US, remains skeptical of the new bill recognising Tamazight as an official language. Ultimately, he believes, it all will depend on how it is implemented as to whether it can achieve what activists have been calling for. Moroccan state-driven actions have amounted to not much than a symbolic effect, at least in the past.

“And the symbolic effect is important,” Silverstein told Fanack Chronicle, “This is precisely the kind of signal that Amazigh speakers have been seeking, there’s been a claim for recognition for a very long time. The sea change is massive in Morocco… if you go back to the 1990s, or even the early 2000s, you were really risking something to express yourself publicly.” The question now, however, is how that translates into actual equality, Silverstein said. “I think there’s still a long way to go.”

There is also the fact that the version of the Tamazight language being incorporated into the education system is a standardised form of many Berber dialects. Moreover, it is now accompanied with the Tifinagh alphabet, which many Tamazight speakers still aren’t familiar with, having been accustomed to write the language in the Arabic or Latin alphabet. Therefore, it becomes yet another language that students have to learn.

In short, despite decades of activism towards incorporating Tamazight as an official language, whether the new legislative developments will accomplish what Amazigh activists consider equal application of Tamazight and Arabic languages is yet to be seen. Political efforts are being made to put in place something that will go beyond cosmetic symbolism. Yet there is plenty of pushback as well, which means the end-goal may still take some time to be reached.