Ever since it became known that 15 of the 19 terrorists involved in the 9/11 attacks in the United States were Saudi nationals, the world has kept its eyes firmly fixed on the culture – and religion – that produced these men.

Wahabbi Islam, a puritanical form of the faith, is the official creed of the conservative kingdom and the ideological foundation of the House of Saud, which presents itself to the Muslim world as the guardians of a pure form of Islam. In fact, it is a controversial interpretation of Islamic tradition, which denigrates and antagonizes not just other forms of Islam but also regards other religions as false. Such ideas lie behind much of the violence in the name of Islam against both Muslims and non-Muslims around the world.

Following 9/11, and under growing pressure from their Western allies, the Saudi rulers promised to eliminate intolerance by reforming the school curriculum.

But 15 years later, school textbooks that foster intolerance and extremism are still in use, according to Human Rights Watch (HRW). A survey published by the rights group in September 2017 found that ‘as early as first grade, students in Saudi schools are being taught hatred toward all those perceived to be of a different faith or school of thought’. Sarah Leah Whitson, HRW’s Middle East director, said, “The lessons in hate are reinforced with each following year.”

It is hard to imagine how the Saudi state can shed some of the basic tenets of Wahhabism without undermining the legitimacy of the House of Saud itself. It was therefore far from clear what Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (often referred to as MBS) – Saudi Arabia’s de facto ruler – meant when he announced in October 2017 that the kingdom would return to “moderate Islam”, since the state founded by his grandfather knows no other Islam than the Wahhabi type.

However, MBS has pressed ahead with some audacious reforms. Removing the religious prohibition on women driving and allowing cinemas to reopen after a ban that had lasted for decades were among his opening gambits. He has also limited the powers of the notorious religious police. Yet his way of going about it – brazen and confrontational – has raised doubts about his real motives. Numerous commentators have described his reform drive as a high-stakes gamble, part of a bigger scheme to consolidate his power within the royal family that could backfire, as his pursuit of greater Saudi influence across the Middle East, particularly in Lebanon and Yemen, already has.

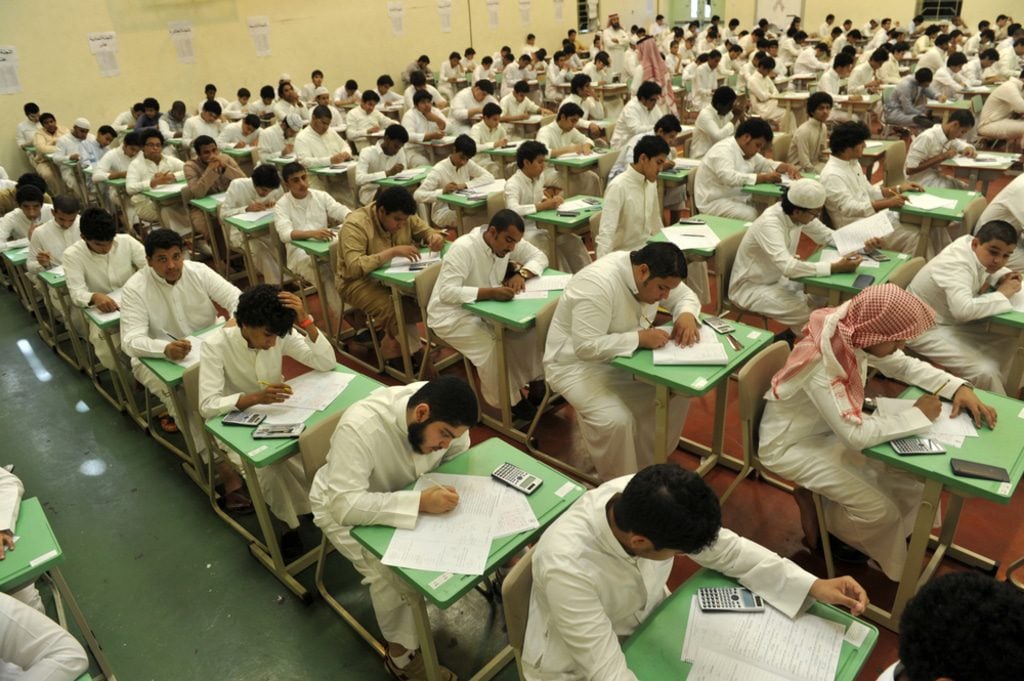

Central to MBS’ wide-ranging reform agenda, which seeks to diversify the economy and reduce dependency on oil – the so-called Vision 2030 – is reforming the education system, which relies heavily on rote learning and little or no critical thinking – hardly the skills needed for a modern economy.

A 2011 survey of the Saudi school system by UNESCO found that the emphasis on Islamic and Arabic language is far greater than other subjects. The number of classes for the former is twice those dedicated to mathematics and natural science.

Similarly, a 2015 survey carried out by Evosys, a data analytics consultancy, found that despite the declared ambition of turning Saudi Arabia into a knowledge-based society, the education system still falls short ‘in terms of meeting the labour market demand of qualified graduates, unbalanced distribution of students across various disciplines and a gap between research carried out by the scholars and community needs, with lack of funds and facilities for researchers’.

This also explains the Saudi reliance on foreign labour in nearly every aspect of modern life, from domestic maids to doctors and pilots.

Vision 2030 aspires to make education ‘contribute to economic growth’ and to ‘close the gap between the output of higher education and job market requirements’. It also hopes to make Saudi universities among the best in the world by 2030. However, it does not detail how it would achieve this within just 13 years.

As several observers have pointed out, some aspects of Vision 2030 have been part of previous Saudi policy and economic and social reform plans. Jane Kinninmont of Chatham House, an independent think tank based on London, wrote:

‘Vision 2030 essentially continues, in amplified and expanded form, policies that the country has had in place for some decades. These have had some successes in generating non-oil growth and encouraging some Saudis to work in the private sector, but implementation has repeatedly fallen short of the ambitious targets that have been set, with the result that the Saudi economy remains overwhelmingly dependent on oil-fuelled government spending.’

To combat growing unemployment, particularly among the youth, the kingdom adopted a policy encouraging employers in the public and private sectors to gradually replace foreign workers with Saudi nationals. Called Saudization, the policy has been in place for over 30 years. However, a lack of qualified labour has driven companies to circumvent the rules to import migrant workers instead of relying on the local and poorly trained workforce.

Today, the country still relies on some 11 million migrant workers to keep the economy running, out of a total labour force of 13 million. At the same time, youth unemployment has continued to rise, hitting well over 12 per cent, according to figures released by the Saudi authorities in July 2017.

Setting lofty goals is one thing, achieving them is another. Turning Saudi universities into some of the best in the world by 2030 is ambitious, to say the least. For decades, Saudi Arabia has invested billions of dollars in expanding its education system. For example, in 2009, the late King Abdullah launched one of the most elaborate education projects in the kingdom: the King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (also known as KUAST) on the Red Sea and endowed it, according to reports, with around $10 billion, making it one of the richest universities in the world. It was built in a record two years and has some of the most advanced teaching and research technologies. It is designed to be a magnet for local and global talent, but it is too early to see the impact – if any – of such a project on Saudi society.

However, investing in the infrastructure alone will not free Saudi society from the shackles of a medieval mindset that governs all aspects of life: the relationship between the ruler and those ruled, between men and women and between native and migrant labour. Scientific thinking needs a socially and intellectually fertile environment to flourish. That environment has yet to emerge in Saudi Arabia.