Introduction

Oman is heavily dependent on oil and gas resources, which can generate between and 68% and 85% of government revenue, depending on fluctuations in commodity prices.

In 2016, low global oil prices drove Oman’s budget deficit to $13.8 billion, or approximately 20% of GDP, but the budget deficit is estimated to have reduced to 12% of GDP in 2017 as Oman reduced government subsidies, According to the World Factbook of the CIA.

Oman is using enhanced oil recovery techniques to boost production, but it has simultaneously pursued a development plan that focuses on diversification, industrialization, and privatization, with the objective of reducing the oil sector’s contribution to GDP.

The key components of the government’s diversification strategy are tourism, shipping and logistics, mining, manufacturing, and aquaculture.

Muscat also has notably focused on creating more Omani jobs to employ the rising number of nationals entering the workforce. However, high social welfare benefits – that had increased in the wake of the 2011 Arab Spring – have made it impossible for the government to balance its budget in light of current oil prices.

In response, Omani officials imposed austerity measures on its gasoline and diesel subsidies in 2016. These spending cuts have had only a moderate effect on the government’s budget.

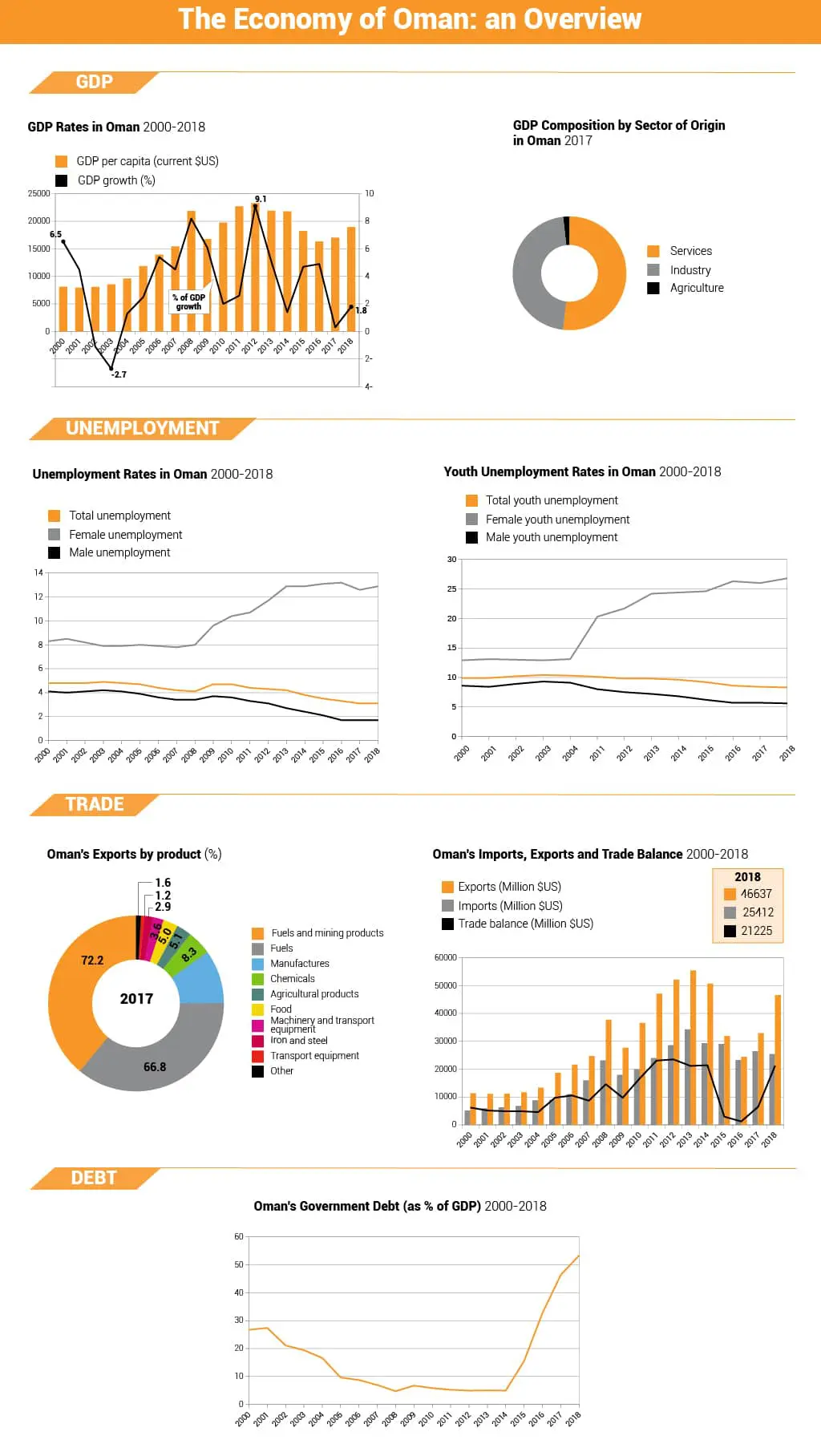

Gross Domestic Product

According to the latest official figures, Oman’s real gross domestic product (GDP) shrunk by 0.9 per cent in 2017, from 5 per cent in 2016. The high growth in 2016 was driven by record levels of oil production and a significant drop in real net taxes (in terms of GDP at production factor prices, the country achieved only 1.8 per cent growth in 2016).

In 2017, Oman committed to the OPEC+ deal, under which the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries, Russia and other producers agreed to curb oil output to 1.2 million barrels per day. The result was a contraction of 2.7 per cent in the hydrocarbon sector, partially compensated by the 0.4 per cent growth in the non-hydrocarbon sector, notably fisheries.

| Indicators | measuring unit | 2016 | 2017 | Change ± |

| GDP (at constant 2010) | Billion US$ | 75.054 | 74.850 | -1.796 |

| GDP growth (annual) | % | 5.4 | -0.3 | -5.43 |

| GDP per capita (constant 2010) | US$ | 16.962 | 16.144 | -0.818 |

| GDP (at current value) | Billion US$ | 66,824 | 72,643 | 5.819 |

Source: World Bank.

On the expenditure side, the overall contraction was driven by weak public consumption and investment. Inflation increased slightly from 1.1 per cent in 2016 to 1.6 per cent in 2017, reflecting a rise in fuel and housing prices.

The World Bank expects Oman’s real GDP growth to recover to 2.8 per cent in the medium term, in line with higher production from the Khazzan gas field, the termination of the OPEC+ deal and the impact of economic diversification investments. The bank also expects inflation to accelerate to 3.2 per cent by 2020, when indirect taxes are imposed.

International Market Position

Oman was ranked 62nd out of 137 countries covered by the Global Competitiveness Index 2017-2018, four places higher than in 2016-2017h, with notable improvements in its macroeconomic environment and higher education and training. The government is currently passing major fiscal reforms to help the economy adapt to the new situation of low oil prices and maintain the sustainability of public finances.

These reforms include cutting fuel subsidies and other distortive fiscal measures, increasing corporate tax and introducing a value-added tax (VAT) system. The latter follows a 2018 agreement by all six Gulf Cooperation Council states to introduce a harmonized VAT regime and customs union, although Oman has announced it is delaying implementation due to slow economic performance.

Overall, the country can rely on strong institutions and infrastructure. However, it needs to continue its efforts to improve education and training systems and radically reform labour markets, which have decreased in efficiency over the past ten years.

| Indicator | Rank (out of 138) 2016–2017 | Rank (out of 137) 2017–2018 | Change in rank ± |

| Institutions | 28 | 28 | 0 |

| Infrastructure | 38 | 36 | 15 |

| Macroeconomic environment | 81 | 66 | 6 |

| Health and primary education | 69 | 63 | 14 |

| Higher education and training | 85 | 71 | 4 |

| Goods market efficiency | 51 | 47 | -40 |

| Labor market efficiency | 82 | 122 | 1 |

| Financial market development | 55 | 54 | -2 |

| Technological readiness | 57 | 59 | -2 |

| Market size | 68 | 62 | 6 |

| Business sophistication | 66 | 72 | -6 |

| Innovation | 76 | 76 | 0 |

| Global Competitiveness Index | 66 | 62 | 4 |

Source: Global Competitiveness Index 2016/2017 and 2017/2018.

Oil

In 2013, hydrocarbon revenues in Oman were 31 billion USD. They accounted for 66 percent of Oman’s exports and 39 percent of its gross domestic product (GDP), according to the Central Bank of Oman. Oman has been more open about its oil and gas reserves than some of its neighbors.

This perhaps results partly from the fact that the country is not a member of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and therefore not concerned about OPEC quotas. An additional factor is the presence of foreign companies that book reserves in Oman, rather than operating solely as service companies.

Moreover, contrary to neighbouring countries, Oman’s oil reserves are often deep and tight, leading to more expensive onshore extraction costs (as much as four times that of Saudi Arabia), and, in recent years, extensive use of enhanced oil recovery (EOR).

According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, Oman’s proven oil reserves are about 5.5 billion barrels. This is smaller than all other Persian Gulf countries except for Bahrain, though larger than Oman’s neighbour Yemen.

Oman possesses offshore fields as well as onshore fields, and the development of offshore fields has, along with onshore EOR, helped to maintain reserve levels for the Sultanate. However, production levels of crude oil and condensate fell during this decade after peaking in 2001 at 960,000 barrels per day (bbl/d).

Natural production declines from aging fields combined with the difficulties of increasing reserves given Oman’s geology resulted in a steady decline to 710,000 bbl/d by 2007. From 2008 onwards, however, new investment and implementation of EOR bore fruit, with average production reaching 919,000 bbl/d in 2012.

One of the most important contributions to the return to production growth is the Oxy led steam flood project at the 2.1-billion barrel Mukhaizna heavy oil field. The company has increased production on the field from 5,000 bbl/d when it started the project in 2005 to 120,000 bbl/d in 2012.

Other projects contributing to the renewed growth, though smaller in scale, include the Rak Petroleum (a private Omani company) and LG (of South Korea) offshore Block 8 that is building up production to 10,000 bbl/d.

Most of Oman’s petroleum production acreage (about 85 percent) is controlled by Petroleum Development Oman (PDO), which is owned by the government of Oman (60 percent share), and the private companies Royal Dutch Shell (34 percent), Total (4 percent), and Partex (2 percent).

PDO has a forty year concession/operating agreement, which began in 2004. In 2008, PDO invested 170 million USD in exploration and appraisals. Other important projects expected to come online soon include the Karim cluster of oil fields being developed by Medco Energi of Indonesia, which is trying to increase output from around 12,000 bbl/d to 30,000 bbl/d. Another is the Rima Cluster of Oman’s Petrogas, which is attempting to boost production from 2,000 bbl/d to 7,000 bbl/d.

Natural Gas

Oman’s gas production increased from 99 billion cubic feet in 1990 to 936 billion cubic feet in 2011 (Source: EIA). Nearly all of the Sultanate’s gas is produced by Petroleum Development Oman (PDO). Oman’s domestic natural gas pipeline system is controlled by the Oman Gas Company (OGC), although OGC has contracted the management of the network to a consortium of private companies.

Oman’s natural gas network spans about 1,100 miles, bringing supplies from production centres to the country’s LNG terminals, power plants, and other domestic end users.

Oman has put large efforts into developing its natural gas reserves, despite its reserves being relatively small for the region. Proven natural gas reserves are estimated by the EIA at 30 trillion cubic feet. This is the least in the Persian Gulf, other than Bahrain, though still a sizable amount by global standards.

For example, it is greater than the gas reserves of the United Kingdom. However, like the United Kingdom, Oman has very high demand for its domestic gas (in 2011, consumption amounted to 619 billion cubic feet). Although this does indicate a high level of economic development in the Sultanate, it also means that Oman, like the United Kingdom, will import more and more gas, despite being a sizable producer.

As with oil, PDO is investing to expand natural gas production, but a number of non-PDO exploration and production projects are also being carried out. Most important is the Mukhaizna field, which is estimated to contain as much as 934 bcm, though this would concern gas in place, not proven reserves. In April 2009, Petronas signed a deal to explore Block 63, Harvest a deal to explore Block 64, and BG a deal to explore Block 60, all for gas.

Oil and Gas Data

- Crude oil production (plus condensate): 918,570 barrels per day

- Natural gas liquids production: 5,400 barrels per day

- Total oil production: 923,774 barrels per day

- Total oil consumption: 144,897 barrels per day

- Proven crude oil reserves: 5.5 to 5.6 billion barrels

- Total refinery crude oil capacity: 85,000 barrels per day

Gas

- Natural gas production: 936.6 billion cubic feet

- Delivered sales gas: 0,498 trillion Btu

- Proven natural gas reserves: 30 trillion cubic feet

Electricity

- Electricity generation capacity: 4.3 gigawatts

- Electricity generation: 18.6 billion kilowatt hours

- Electricity consumption: 15.3 billion kilowatt hours

Revenues

-

- Net nominal oil export revenues: 36.6 billion USD

- Net nominal per capita oil export revenues: 5,926 USD

- Gross domestic product: 59.95 billion USD (fixed official exchange rate)

Source: EIA

Infrastructure

Oman’s infrastructure, especially its road network, has expanded greatly in recent decades. In 1970, before the accession of Sultan Qaboos to the throne, Oman had only ten kilometres of roads. According to Oman’s Ministry of Transport and Communication, Oman now has 12,402 kilometres of paved roads and 17,009 kilometres of graded roads.

There are six main ports in Oman—Matrah, Salalah, Qurum, Sur, Sohar, and Duqm—and several smaller fishing harbours. The ports of Sohar (partially owned by the Port of Rotterdam, the Netherlands) and Duqm have been assigned particular importance to Oman’s industry and trade. The old port of Matrah, traditionally a fishing and trading port, will be developed to serve tourism and leisure travel.

Despite the significant growth in the last forty years, Oman lags behind its Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) neighbours in infrastructure, according to Middle East Economic Digest (MEED). Infrastructure that has been built since 1970, particularly in the capital area (Muscat), is struggling to cope with the high rate of growth in mobility. Cities, towns, ports, and airports are far apart, and the current network of roads does not adequately serve Oman’s industry and trade and its tourism potential.

It is this potential that needs to be realized, in order to boost the national economy. Protests by Omani nationals in recent years, demanding more jobs, have shown that the country needs economic diversification to create more employment opportunities. Moreover, Oman has just 17 years of oil production left (at current extraction rates) and hence is under more pressure than other GCC states to invest in non-oil sectors.

To support this diversification, expansion of the current transport network is needed. Realizing this need, Oman is investing heavily in upgrading the road network, developing a national railway system, and expanding airports and seaports to serve the growing tourism sector and the development of industry and trade.

Ahmad bin Hassan al-Dheeb, undersecretary of the Ministry of Commerce and Industry, told MEED last year that the sultanate would spend about 20 billion USD on transport projects in the coming years.

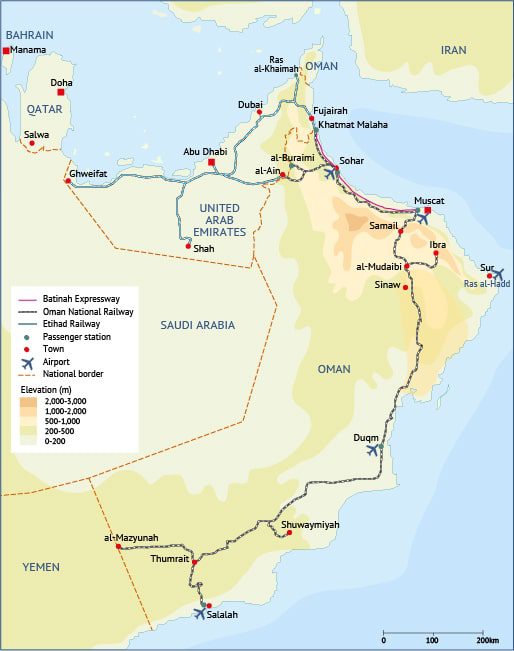

Railway

A new national railway, connecting the UAE border with the Port of Sohar, Muscat, the new port of Duqm, and the southern city of Salalah, will be part of a wider railway network in the GCC. That network, which is planned to extend from the Iraqi border in Kuwait to Muscat, has been in development since 2008. The Omani government decided to extend the railway towards the south, eventually connecting southern Oman with the Etihad Rail network in the United Arab Emirates and further afield.

This is expected to serve Oman’s ports on the Arabian Sea coast and maximize their potential. In this way, the sultanate is trying to bring international shipping companies to its shores, taking advantage of rail transport, instead of facing delays at crowded ports in the Gulf. In addition, Oman would offer an alternative route for freight transport in case regional tensions should disrupt shipping through the strategic Strait of Hormuz (through which about one-third of the world’s oil supply is currently shipped).

The diesel-powered rail line will also feature passenger services, improve access to remote areas, and boost economic activity in the regions beyond the capital. Yet, given the fact that the car remains the preferred mode of personal transport in the Gulf, it remains to be seen whether many Omanis will use the train.

Construction on the 2,244-kilometre long railway, costing an estimated 15 billion USD, is planned to begin in early 2015. Design, planning, and construction will be carried out by consortia of international companies, but the Omani government is seeking to maximize local staffing and manufacturing capabilities, according to MEED. As with the construction of roads in the sultanate, the double-track railway will pose an enormous engineering challenge due to Oman’s mountainous and rocky terrain, requiring many bridges, tunnels, and underpasses. The network is planned to be operational by 2018 or 2019, but MEED characterizes this as ‘overly ambitious’, given the current rate of the procurement progress.

According to Construction Week Online, Oman’s logistics market is set to grow by 50 percent, to 12 billion USD, by 2017. This would mean a positive outlook for Oman’s growing role in logistics, and consequently, for the country’s economic diversification.

Roads

Another cornerstone of investment is the construction of new roads and the upgrading of existing ones. In its five-year economic plan (2010-2015), Oman has allotted 3.2 billion USD for road construction, with this infrastructure category ranking second highest, after airports. This indicates the importance the government has attached to improving Oman’s road network.

Areas that used to be remote and inaccessible have already been connected with Muscat and other towns in recent years, through new roads and dual carriageways. Contractors have succeeded in overcoming the country’s diverse geographical conditions, which pose an engineering challenge.

Whole mountains have been blown up to make way for roads, or motorways have been constructed right across intervening mountains, as is seen in the case of the dual carriageway connecting Muscat with the suburb of al-Amarat.

A better land connection to the UAE has been planned, with the construction of the Batinah Expressway, connecting Muscat with the UAE border and the port of Sohar (at a cost of approximately 2.59 billion USD, according to MEED). The Batinah Expressway, the largest of all Oman’s road projects, will primarily support the port of Sohar, which has grown significantly in recent years.

As the first four-lane motorway in the country, the road will further open up Sohar to markets in the United Arab Emirates. Another major project is a new dual carriageway planned to improve access to the Musandam peninsula, running through mountainous terrain and including seven tunnels and 18 bridges, at an estimated cost of 1 billion USD.

Airports

Oman is spending billions of dollars to improve its airport infrastructure as part of an effort to boost its economy, and the tourism sector in particular. Muscat International Airport, which handled 6.8 million international passengers in 2012, is currently being expanded. A new passenger terminal, runway, and control tower are planned to open in late 2014 and are set to increase the airport’s passenger capacity to 12 million by 2014.

Future extension phases are planned to expand capacity to 48 million passengers (which is still far less than Dubai International Airport, for example, which handled more than 66 million passengers in 2013). Salalah airport, in the governorate of Dhofar, is also being expanded and will see its capacity grow to one million passengers a year. In addition, regional airports are planned for Sohar and Duqm (under construction) and Ras al-Hadd and (supporting the tourism sector).

While the outlook looks promising, Oman faces the huge challenge (apart from its challenging terrain) of securing the resources and skills needed to execute these projects, while so many other major projects are under way in Oman and elsewhere in the Gulf.

Tourism

Oman has great potential when it comes to tourism. With long coastlines, dramatic mountain scenery and many historic sites, including four UNESCO heritage sites, the tourism sector is a focal point of diversification. The Ministry of Tourism aims to attract 12 million visitors by the year 2020. Oman received 1.36 million tourists in 2007 (Ministry of Tourism 2011); the figure further increased to 1.96 million visitors in 2013 (NCSI 2014).

According to the World Travel & Tourism Council, the direct contribution of tourism to Oman’s GDP amounts to 3.3 percent of Oman’s GDP (2014) and with 37,000 jobs generated, it accounts for 3.5 percent of total employment (2014). With these results, Oman is ahead of Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and Qatar, but behind the UAE and Bahrain.

According to MEED, the reality of the tourism sector does not always match up to Oman’s potential. Omani nationals spend more on foreign trips than the income Oman receives from international visitors. The tourism trade gap was around 380 million USD in 2011 (MEED). MEED cites the lack of infrastructure and investment.

However, the government has been investing heavily in the sector. One of the main projects now underway is the major upgrade and expansion of Muscat International Airport. The new terminal building that is being built will have a capacity to handle 12 million passengers a year. An additional runway is being constructed, while the existing runway will be upgraded to handle the super-sized Airbus A380.

In the south, Salalah International Airport is planned to expand to a capacity of 1 million passengers a year. Smaller airports are planned in Sohar, Duqm, Adam and Ras al-Hadd. Several large tourism projects are also underway (most will be completed within the next five years).

These include ten resort-style developments under construction in various parts of the country plus a mega 6000-seat Convention Centre on a site close to Muscat International Airport. The Sultan Qaboos Port in Muttrah, traditionally designed to handle cargo, will be transformed into a port dedicated to tourism and catering for cruise ships. All cargo trade will be moved to the port of Sohar.

Informal Sector

Although difficult to assess, the significance of the informal sector seems relatively limited. Handicrafts and traditional industries, produced by women, and trading networks are considerable. Production and trading by migrants largely from Pakistan and India, is another segment of the economy insufficiently documented statistically. Most of the expatriates employed in the commercial sector run retail businesses, as well as farms, more or less independently. Little is known about the actual size and turnover of these businesses.

Fisheries form a relatively important income-generating sector. Some 15,000 fishermen are involved in this sector, which provides a source of living to about 100,000 people. Fisheries play a dominant role in the economy of the coastal regions, which occupy a 2,092 kilometre coastline. Most of the fish is caught through traditional fisheries (133,000 tons out of 148,000 tons in 2007).

In 2011, production was 158,723 tons (Source: FAO). Although an estimated 4.3 million tons are available for fishing, studies indicate that harvesting should not exceed 175,000 tons annually in order to sustain future catch. The Marine Science Centre located in Muscat conducts this type of research in fisheries. Industrial fisheries are located in the area around the capital.

Already at an early stage, the government promoted agriculture and fisheries to reduce Oman’s reliance on food imports. Nevertheless, despite the investments and the apt response of the private sector, their relative contribution to the economy has declined with the expanding oil industry. In the last Five-Year Plan further development of fisheries was pursued through supporting modernization of the fleet and upgrading of infrastructure related to export.

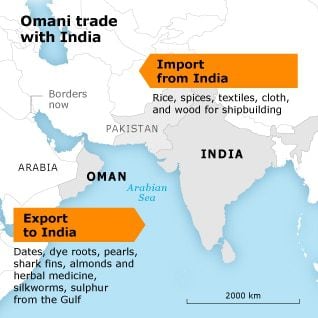

Trade is now the motor of the economy and its diversification. Re-export is the focal point. 60 percent of the goods arrive by sea. Thus trade has regained its traditional significance. Maritime activities used to supply the Omani population with a supplementary source of income. Oman’s location on the south-eastern corner of the Arabian Peninsula, bordering the Gulf and the Arabian Sea, enabled its people to participate in long-distance trade networks.

Its ports, located favourably as regards the monsoon winds and strategically placed between the African and Asian continents, functioned as warehouses. In addition, Omani products such as incense and dates used to find their way to the intercontinental markets. At present, oil, gas and a growing number of other commodities have taken their place.

The trade and commerce sector, including construction and contracting, is consistently expanding through the consumption linkage with the oil industry. Consumer goods boost the import and distributive trade. For example, an intricate and efficient distribution network has developed between Dubai, the capital area of Muscat and regional markets. In recent years, tourism has increased and with 1.8 million visitors (NCSI 2012) contributed to around 3 percent of Oman’s GDP (World Travel & Tourism Council 2013).

Diversification

Oman is paving the way forward for sustained development beyond the finite oil-based economy. Diversification aims at widening the economic base and securing jobs for its population. It has been an objective in subsequent five-year programmes. The sectors aimed at are the manufacturing industries, tourism and trade. Traditional sectors such as agriculture and fisheries also receive investments and other incentives.

Manufacturing is a focal point in the diversification strategy. The current Plan aims at enhancing the growth of non-oil sectors at an annual rate of 7.8 percent on average. The gas based industries, the tourism sector and non-oil merchandise exports of Omani origin are set to realize an annual growth rate of 10 percent or more. The industrial sector is to contribute some 15 percent to the country’s GDP by 2020.

Billions of dollars are being invested in gas-based industries such as Sohar Aluminium Smelter and the Polyethylene and Oman Aromatics projects. Capital intensive industries such as Oman Oil Refinery and Oman LNG receive large investments, even though these industries offer restricted employment opportunities.

However, diversification is proving difficult to realize for a number of reasons. The oil industry is basically an enclave activity with few backward and forward linkages to other manufacturing industries. This was especially so when crude oil was predominantly exported from Oman. This trend has reversed with the development of the petrochemical industries.

The oil sector tends to draw capital and labour from lagging sectors such as other manufacturing industries, agriculture and fisheries, although the oil price volatility makes planning difficult.

The government sees an important role for the private sector, which traditionally plays a keen role in economic development, to attain the above-mentioned goals.

According to Vision 2020, the private sector is effective, self-reliant, and competitive, the main vehicle for national income generation, and the moving force behind job creation, assuming its social and environmental responsibility. Electricity, water, and other commodities are being privatized.

Proclaiming a capitalist approach yet recognizing the fragility of the economy, Oman seeks to benefit from the protective provisions laid down in the World Trade Organization agreements.

Labour Immigration

The exploitation of oil in the Arabian Peninsula, which began in the 1920s but increased considerably after World War II, induced a national and international movement of labour in the Middle East. In the early 1980s, more than 5 million people were involved, by the early 21st century, this number had almost doubled. Quantitative and qualitative demand far outstripped the national labour supply in oil-endowed states.

Initially characterized by an inter-Arab exchange of labour, the labour force soon turned international, being dominated by Asian immigrants from the Indian subcontinent. They were keen to participate in the economic boom relatively close to home in exchange for lucrative salaries (wages for unskilled labourers from Bangladesh in the early 1980s, were five to six times higher in the Gulf countries than at home). The gradual shift from construction to services increased the proportion of labour from Far East Asian countries such as Korea, Taiwan, the Philippines and Thailand.

At first, no restrictions applied to labour immigrants, apart from the sponsor system. However, with the onset of ‘Omanization‘, a more restricted approach was introduced. Nowadays, all expatriates coming to Oman need a work permit supplied by a national company, which is issued on a yearly basis. The sponsor is responsible for the payment and the physical well-being of the sponsored person. If a problem arises both migrant and sponsor have the right to obtain judicial advice from authorities or plea a court case.

Restrictive regulations concern the number of foreign workers permitted per company. Certain sectors have become closed for non-nationals, such as the taxi business and public transportation. This policy has been expanded to various sectors, with varying success. For example, the ban on foreign hairdressers was soon lifted when it became apparent that few Omanis were willing to enter this sector. Foreign ownership of companies is limited to a maximum of 49 percent.

Legal Framework

Oman established a Labour Law in 1973, which regulates amongst other things industrial relations and employee affairs, employment contracts, work descriptions, and working hours. In 1991, the Social Insurance Law was enacted. Companies with more than 50 employees need to establish representative bodies for trilateral representation.

The labour inspection at the Ministry of Labour monitors adherence to the rules. It settles disputes and observes the grievance procedure. The Ministry of Manpower received 297 grievances from labourers in 2008. New royal decrees in 2003 and 2006 brought the Labour Laws into further accordance with international labour standards.

Improvements included procedures for union activity, collective bargaining, and strikes. A Court of Justice caters for government employees’ grievances. In 2003, in letters to the six states of the Gulf Cooperation Council, Human Rights Watch strongly urged their leaders to endorse the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families.

The ministry proclaims a policy of conservation of renewable natural resources, marine environment and fish resources, grazing lands, forests, and wildlife. Projects include the development of 18 recharge dams, 35 storage dams, census of wells and of the traditional irrigation system (falaj) to make better use of water resources. Marine environment and fisheries projects concern fishing research, improvement of statistics and mangrove planting. Agricultural environment conservation projects are improving irrigation techniques and proclamation of natural reserves. Sustainable development indicators monitor the process.

Sudtainability

The ministry proclaims a policy of conservation of renewable natural resources, marine environment and fish resources, grazing lands, forests, and wildlife. Projects include the development of 18 recharge dams, 35 storage dams, census of wells and of the traditional irrigation system (falaj) to make better use of water resources.

Marine environment and fisheries projects concern fishing research, improvement of statistics and mangrove planting. Agricultural environment conservation projects are improving irrigation techniques and proclamation of natural reserves. Sustainable development indicators monitor the process.

Latest Articles

Below are the latest articles by acclaimed journalists and academics concerning the topic ‘Economy’ and ‘Oman’. These articles are posted in this country file or elsewhere on our website: