Related Articles on Fanack

Below are the most recent related articles concerning the topic ‘Defence and Security‘ and the ‘United States of America‘.

On 8 January 2020, a barrage of Iranian cruise missiles slammed into the American section of the al-Asad military base in Iraq. After weeks of escalating tensions between the United States (US) and Iran, the strikes have so far been the peak of violence in this latest round of clashes between the two nations. However, as the Iraqi parliament voted to order US troops out of the country following the flare-up, attention has turned to the US military footprint across the Middle East and around the world.

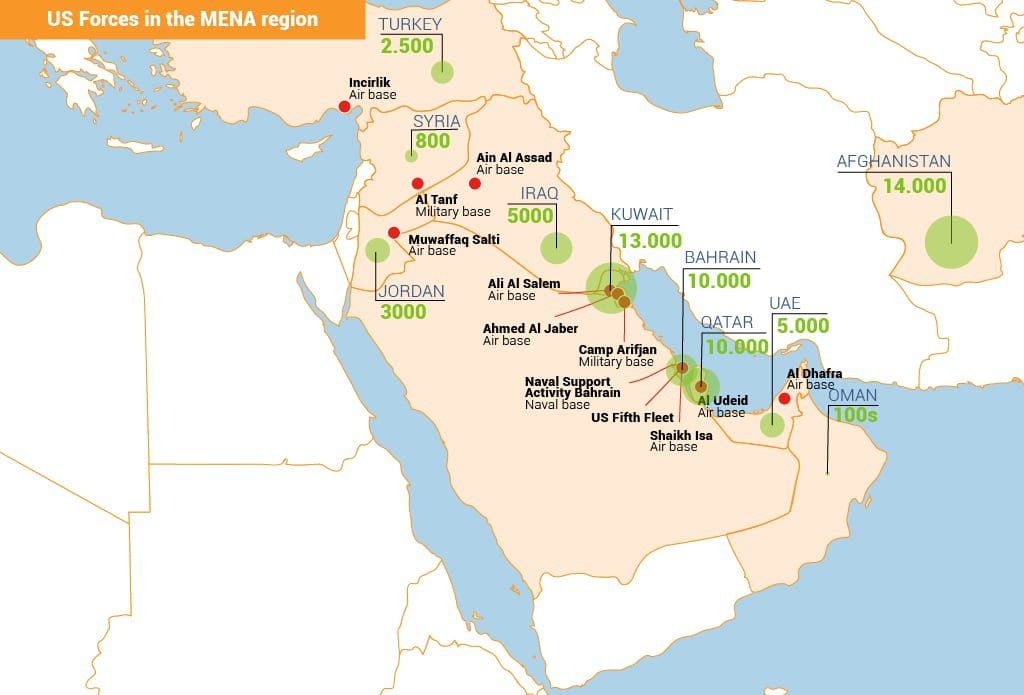

The US operates at least 30 military bases in the Middle East, ranging from small outposts in Syria and military encampments shared with host nations to airbases under full US control. Some are large and visible while others remain highly secretive, likely managed by a combination of CIA or US special forces personnel. These range from a navy-run medical research lab in Egypt and naval and airbases in Qatar (the biggest in the region) and the United Arab Emirates to remote outposts in the contested desert zones of Syria.

The US’ archipelago of military bases across the Middle East represents first and foremost the ambition and reach of the US armed forces. The ability to garrison troops in or near countries that they may be called upon to fight in gives the US an immediate head start in the run-up to any armed conflict. Just as importantly, it also gives the US staging posts around the world where they can legally amass troops and supplies ahead of any potential fight.

The agreements for bases with host countries have historically been relatively loose, allowing the US to make use of such facilities for transport and detention for the now infamous CIA ‘black site’ programme. But less sinister purposes have included the use of Incirlik airbase in Turkey for humanitarian and military operations in Afghanistan or the build-up of US troops in Saudi Arabia ahead of the 2003 invasion of Iraq.

For countries like Turkey, the hosting of US military assets also represents the success of US diplomacy and alliances. The two airbases at Incirlik and near Izmir house some of the US’ most important forward-deployed air assets, from U-2 surveillance aircraft to the reported deployment of nuclear weapons. In an era of strained US-Turkish relations, this deployment is a sign of the enduring strength of this alliance as well as of Turkey’s importance to NATO’s military footprint. The bases are also a hangover of the Cold War, when the American military found itself securing much of Europe and as far east as Turkey from possible Soviet invasion.

Not that these bases have not suffered from the countries’ deteriorating ties. Several times Ankara has threatened to use Incirlik as a bargaining chip in its ongoing battle of wills with successive US administrations’ over everything from human rights to Syria. While not as symbolic as embassies, these bases do represent US military might and, while they rest on the sovereign territory of a host country, their legal status does make them vulnerable to rhetorical attack and diplomatic wrangling when these erstwhile American allies become embittered by Washington’s policies.

Other bases have arguably been won by military, rather than diplomatic, means. Following the war in Iraq, even after the announcement of the end of major combat operations and the withdrawal of the vast majority of US forces in 2011, the US retained several military bases in the country. These include part of the sprawling al-Asad airbase in the west as well as facilities in Baghdad and the Kurdish north. Since the end of the official US war in Iraq, like the large US airfields and facilities in Afghanistan, these bases have been a key hub for special operations raids against the Islamic State (IS), coordination with local forces combatting IS as well as the ongoing training and professionalization of Iraqi and Afghan military forces.

While this may ostensibly serve purely Iraqi interests, the ‘Americanization’ of Iraq’s military – from its choice of US-bought weaponry to personal relations between the two countries’ military leadership – pulls a major centre of power in Iraq towards the US sphere of influence and away from Iran. It is difficult to say how effective such a secondary goal has been – the primary goal being equipping the Iraqi state with an effective counter to insurgent groups. However, the elite units that the US spent the most time and resources on (mainly Iraq’s Golden Division) ably took on the lion’s share of the bloody fight against IS in Mosul and have remained one of the most impressively non-sectarian institutions in Iraq.

Until Baghdad’s recent change of heart, US forces remained in Iraq technically at the invitation of the Iraqi government (a legal status that also has enabled their air war against IS in the country). In contrast, the US mans bases and small outposts in Syria despite the wishes of the (still internationally recognized) government in Damascus. In Syria, the US presence is a legacy of American support for its Kurdish proxy in the war against IS and its largely unsuccessful backing of rebel groups in the southern desert. This presence has allowed Washington to partly dictate the direction of the conflict and, according to President Donald Trump, it has secured valuable oil resources for the US and its allies.

Yet the American presence has been fickle. Despite Trump’s impromptu withdrawal of most US forces in October 2019, some still remain in small numbers, helping a fragile status quo between Kurdish and Turkish forces and ostensibly keeping the resurgence of IS in check. While their presence is welcomed by the Kurds they work alongside, as US forces provide a powerful deterrent to outside attack, their legally questionable status in the country marks this presence more as a prize won in battle than a legacy of years of cooperation.

While the ability to base personnel and materials in countries far from the homeland is no doubt a boon for the US, some host countries see so much benefit for themselves in the agreement that they are willing to pay the US for the privilege of hosting troops. Indeed, under Trump, the White House’s policy has been to demand payment for the garrisoning of US troops, in effect turning the US military into a mercenary force.

Estimates on what US wars and military action in the Middle East have cost the US taxpayer since 9/11 go as high as $6.4 trillion. Since coming to office, Trump has, by his own account, secured billions of dollars of arms sales or payments to secure the presence of troops in places like Saudi Arabia, where Washington has based troops off and on since before the Gulf War. With military facilities the breadth of the country, this must surely provide some peace of mind for the Saudi leadership, even if the Trump White House’s commitment to long-standing relations has been repeatedly called into question.

Today, hundreds of troops are stationed in Saudi Arabia, in what has at times been a contentious issue for many Muslims, given these troops’ proximity to two of the most holy sites in Islam (a gripe that figures such as al-Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden have taken full advantage of). In light of the tensions with and occasionally attacks by Iran or their proxy forces on Saudi soil, US boots on the ground are a strong deterrent against invasion – although evidently not attack – and from Riyadh’s perspective commit Washington to the collective defence of its allies in the Gulf. Given his attachment to demanding payment for services rendered, it is unclear if Trump’s view on committing further US troops to a possible Saudi defence is quite as sure. Regardless, the troops’ presence (and their quantity) underlines the strength of the US-Saudi alliance to all onlookers.

The US has long valued its role in the Middle East, whether by means of military muscle or diplomatic influence. Both have helped guarantee the presence of US troops in an archipelago of bases and outposts that is unmatched by any other country save perhaps Iran. With an outsized say in the region’s stability thanks to the promises of security for allies and threat (and ease) of military action for foes that such an infrastructure provides the US, American boots on the ground will remain a key pillar of Washington’s Middle Eastern policy for years to come.

Below are the most recent related articles concerning the topic ‘Defence and Security‘ and the ‘United States of America‘.