China's Middle East policy is mainly shaped by economic factors. Acclaimed journalists & academics provide Arab perspective of the phenomenon

Introduction

In order to understand China’s Middle East policy, it is necessary to take into account the political ideology that informs the Chinese state as well as the leaders who have dominated its political landscape over the decades.

Between 1949 and 1976, Mao Zedong, the founding father of the People’s Republic of China, governed according to his personal perspective on Marxist-Leninist theories. This later became known as Maoism and was widely perceived as guiding revolutionary movements around the world. Under Mao, China sought to distance itself from the ‘imperialist West’ and viewed itself as the ‘guardian of revolution’ in the world, including the Middle East. Even when China was facing its own economic difficulties in the 1950s and 1960s, it never wavered in its military and diplomatic support for the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO).

After Mao’s death, Deng Xiaoping assumed power in 1978. He put China on a path of economic development while downplaying ideological conflicts on the international stage. Hence, since the 1980s, China’s chief concern has been accelerated economic growth, which significantly increased its need for imported oil. In this context, China began to seek and strengthen diplomatic relations with the oil-rich countries of the Middle East, and its interests in the region changed to reflect its economic needs.

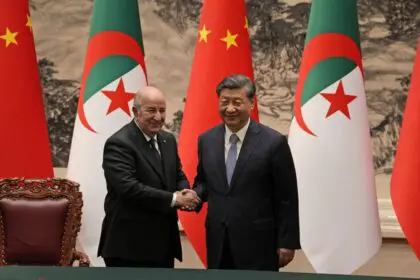

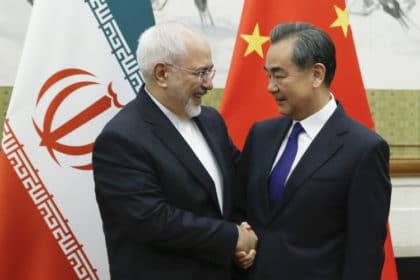

Over the years, and in sharp contrast to the United States, observers have described the relationship between China and the Middle East as politically ‘baggage free’. Since it became a net importer of oil in 1992 and subsequently the world’s largest importer of crude oil, China has been predominantly interested in securing long-term oil supplies and has avoided becoming entangled in the internal politics of the countries with which is does business. It maintains strong ties with the region’s leading powers – Turkey, Iran, Egypt, Saudi Arabia and Israel – making it perhaps the only country able to do so.

Mercantilist Approach

Deng Xiaoping’s famous quote, “keep a cool head and maintain a low profile. Never take the lead but aim to do something big,” goes a long way to explaining Chinese foreign policy. Beijing has, unsurprisingly, taken a mercantilist approach, which tries to avoid political fights with major powers. To a lesser extent, as current leader Xi Jinping has moved away from Deng’s principle of non-interference with China’s Asian neighbors, opting instead for a more aggressive and interventionist approach, Beijing has continued to adhere to its old mercantilist policy the farther from China one gets.

The 2011 Arab Spring combined with former President Barack Obama’s often hands-off policies in the region proved to China that the Middle East is too important to be left to others, and that neglecting it could be at China’s peril. Under Xi, the country has seemingly decided to stop watching from the sidelines while the region descends into chaos. Instability in the Middle East is, after all, a direct threat to Chinese interests, particularly the flow of resources (imports of oil and raw materials and exports of consumer goods), and the safety of Chinese citizens working in the region.

Nevertheless, China’s role in the United Nation’s Security Council (UNSC) has provoked anger and frustration when it comes to Syria. Syrian President Bashar al-Assad – a close ally of China – has thus far escaped any international legal action for the crimes he has committed during the six-year Syrian war. China has so far vetoed six Western-backed Syria resolutions (Russia has vetoed eight), several of which aimed to tackle the use by the Syrian regime of banned chemical weapons and to resolve the conflict.

Arab Policy Paper

Yet the Syrian war also offered China an opportunity to be more involved in the region, an opportunity it could not pass up. In late December 2015 and early January 2016, Xi invited Syrian Foreign Minister Walid al-Moallem and the head of the opposition Syrian National Coalition (SNC) to high-level meetings in Beijing in an effort to promote a peaceful resolution. On 13 January 2016, Beijing released its Arab Policy Paper, a vague but seminal document articulating China’s interests in the Middle East.

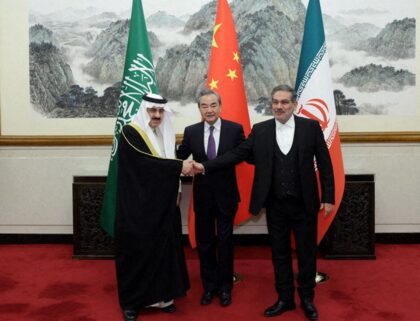

After the Saudi embassy in Tehran was ransacked, Xi dispatched Deputy Foreign Minister Zhang Ming to both Tehran and Riyadh, urging both sides to exercise calm. Xi also signalled his support for Yemen’s internationally recognized government, which was ousted by Shiite Houthi rebels whom Saudi Arabia regards as a proxy for its regional rival Iran.

In March 2016, China announced it was posting its first-ever high-ranking military envoy in Syria, and in April 2016, its Ministry of Defence reported that construction of the first overseas military base had started in Djibouti, a small but highly strategic country on the Horn of Africa.

This diplomatic hyperactivity reflects China’s growing ambition to strike a balance between its original ‘soft power’ foreign policy and its more interventionist approach under Xi.

However, maintaining close and comfortable relationships with numerous Middle Eastern states will be a challenge in a region where these states frequently do not have such relationships with each other.

Given its dependency on oil, China remains the main beneficiary of historically low oil prices. This makes the Iranian-Saudi divide a genuine concern. Home to the world’s largest conventional oil reserves, the Persian Gulf, across which Iran and Saudi Arabia face each other, is critically important to China’s resource-intense economy. As a result, China is keen to maintain good relations with both countries while closely monitoring any escalation in tensions.

The One Belt, One Road initiative

Finally, China’s foreign policy is now tied to its most ambitious economic development project in history: The One Belt, One Road initiative.

The initiative calls for massive investment in and development of land and sea trade routes, with the aim of stimulating Asian economic growth and creating new markets for Chinese goods and services. It is the solution, China says, to the currently stagnant economy.

A restive Middle East is thus a major obstacle to China’s ambitions. An additional concern for Beijing is the country’s Uighurs, Chinese Muslims who are believed to have joined the Islamic State in their hundreds and who could pose a real threat to the One Belt, One Road initiative on their return.

Latest Articles

Below are our latest articles concerning China and the Middle East and North Africa.