Approximately 200,000 years ago Stone Age people, who originated in the deeper Africa, came to Tunisia as hunters, gatherers and fishers. As Tunisia was much wetter than it now is, its south was a savannah with forests. With the changing climate following the last Ice Age, about 8,000 years ago, the country became drier, and the Sahara developed in southern Tunisia. The Capsian culture (named after the town of Gafsa) later arrived from the east. The Capsians raised crops and introduced village life into Tunisia. They are also known for their pottery.

Carthage

In about 1200 BCE, the Phoenicians arrived in North Africa, including what is now Tunisia. Throughout the Punic and Roman eras, Tunisia was the primary area of Phoenician settlement, in a region traditionally inhabited by Berbers. The Berbers lived in farming villages that comprised tribal units with a local leader, assisted by a council of elders. The first Phoenician settlement was at Utica, north-west of Tunis.

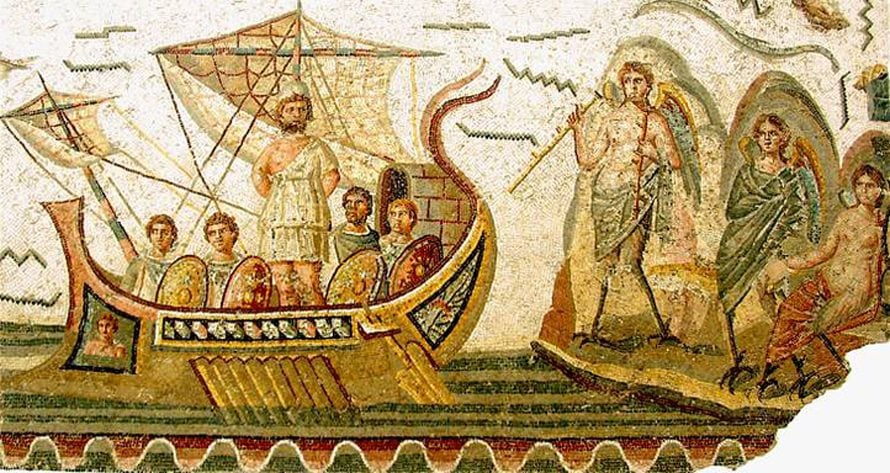

The most important Phoenician settlement, however, was to become Carthage, a city that was founded around 810 BCE near present-day Tunis. According to a legend, Carthage was founded by the daughter of Pygmalion, a king of Tyre. The city was, in any case, created partly to counter the increasing Greek influence in the area. Carthage would quickly become the most important power in the region, controlling, as it did, the coast from what is now western Libya to the Atlantic.

Once the Phoenicians controlled large parts of the coastline, they began to settle inland, especially in the Medjerda Valley and the Cap Bon Peninsula, which offered fertile land that the Phoenicians could use for agriculture. The Carthaginians would eventually fight the Greeks over the island of Sicily and took control of it in the 3rd century BCE.

Carthage engaged in three Punic wars with the Roman Empire. The name ‘Punic’ stems from ‘Punici’, the Latin word for Carthaginians (Phoenicians). In 263 BCE, Rome attacked Carthage for the first time, with the aim of winning Sicily back. The war, led by the general Hamilcar Barca, lasted twenty years before Carthage, by then almost bankrupt, had to surrender. Only four years later, the Romans also took Sardinia and Corsica. Growing bankruptcy resulted in further troubles for Carthage, when unpaid soldiers began to protest and revolt.

The Cathaginians in the second Punic war were led by Hannibal Barca, the son of Hamilcar Barca. Hannibal took control of Spain in 221 BC and, having already sworn an oath of enmity to Rome at the age of nine, soon headed for Italy with an army of 90,000 infantry, 12,000 cavalry, and 37 elephants (only 23,000 soldiers and 17 elephants survived the crossing of the Alps). While Hannibal was successful on the battlefield – most famously at the Battle of Cannae, where he defeated a Roman army of 80,000 – he was unable to take Rome, whose forces greatly outnumbered his.

In order to defeat Carthage, which had been substantially weakened by the first two Punic wars, Rome launched the third Punic war, in 149 BCE. The Roman army came took Utica, the old Phoenician city, after three years of fighting. The war left the city and its surroundings devastated. This was the end of Carthage’s independent existence.

The Roman Era

Having taken control of Carthage following the third Punic War, the Romans initially left many of its new acquisitions to local Berber rulers of Numidia, the ancient Libyan kingdom in Algeria and a smaller part of western Tunisia (202-46 BCE). Numidia had previously been marginalized by the Carthage domination of the region, but it managed to establish a kingdom that included Libya and western Algeria. On several occasions, Rome attempted to split the kingdom to limit its regional dominance, before eventually taking full control of it, in about 46 BCE.

The following centuries witnessed a long period of prosperity in what is now Tunisia. The Romans eventually rebuilt and reorganized large parts of the Carthaginian territory and its cities. Carthage was rebuilt by Julius Caesar and would become the third city of the Roman Empire and the capital of the province of Africa. Other cities that were rebuilt include Chellah, Volubilis, and Mogador (in Morocco). People from across the Roman Empire came to Carthage, attracted by the rich agriculture of the surrounding areas. For example, the Tell Plateau and the Medjerda Valley produced more than 60 percent of the empire’s wheat. The city not only became an economic centre but also prospered culturally under the Romans.

While some Berbers remained poor under Roman rule, there are also instances of Berbers who managed to rise in society, such as Apuleius, a prose writer who travelled throughout the Roman Empire. Several Berbers even received Roman citizenship. Wealthy inhabitants created theatres, baths, and temples, some of which still exist, in ruins, as at Dougga, Tunisia’s most important Roman site and an UNESCO World Heritage Site. It is located on a hill in the countryside of northern Tunisia and comprises the best preserved remains of a Roman city in all of North Africa.

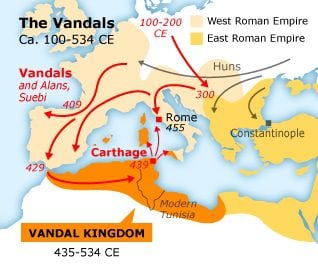

The Vandals

In the 5th century CE, King Gaiseric of the Vandals, a tribal group of Germanic Arian Christians, together with the Alans, their Iranian allies, attacked Rome’s lands in North Africa, which they believed would be easy to conquer. In 429, about 80,000 people – men, women, and children – travelled to Numidia, west of Carthage.

In 439 the Vandals took the city of Carthage, which would become the heart of their kingdom. In order to ensure their supremacy, the Vandals formed alliances with the Berbers. Gaiseric expanded his territory and in 455 took Rome, a city weakened by internal discord. Gaiseric also controlled Sicily, Sardinia, and Corsica.

Although they initially entered an alliance with the Vandals, the Berbers would eventually suffer severe religious persecution under Vandal rule. Over the years, however, the Berbers became stronger and eventually threatened the security of the Vandals. The Vandals built no economic or cultural infrastructure, a fact that eventually contributed to their decline. Their rule over the area that includes present-day Tunisia lasted less than a century.

The Byzantine Empire

Justinian, who ruled the Byzantine Empire from Constantinople, revived the eastern part of the then Christianized Roman Empire and, having similar plans for the western territories, sent his general Flavius Belisarius to fight the Vandals, which Belisarius did successfully in 533. This paved the way for 150 years of Byzantine rule and resulted in the increasing influence of Christianity in the region that includes Tunisia. Yet direct Byzantine rule was limited largely to Tunisia’s coastal cities, while the interior of the country was still mostly controlled by various Berber tribes.

At the beginning of the 7th century, the Byzantine Empire faced several challenges that would shape it for years to come. At that time, the Byzantines were frequently at war with the Sassanid Persians. While these wars generally resulted in only minor border changes, at the beginning of the 600s CE, the Byzantine Empire was weakened greatly by the defeat of its Emperor Maurice by the Sassanid Persians and the latters’ subsequent invasion under Chosroes (Khosrow) II.

Heraclius, the son of the exarch of Carthage, became Roman emperor in 619 and would eventually restore the empire. He built defences and reorganized the government to counter the Persians, who had continued their invasion in the face of little resistance. Heraclius took Antioch in 611, Jerusalem in 614, and Alexandria in 619. When the Persians attempted to take Constantinople, Heraclius moved a Roman army to defend the city. The battle unexpectedly turned in favour of Heraclius’ troops, and in 628 they killed the Persian Shah, Chosroes II. With a weakened Persia, Heraclius was able to regain control of the area that now includes Egypt and Syria.

The Byzantine Empire would, however, almost simultaneously come under a new threat, from the south. The Prophet Muhammad (570-632) gave rise to a new religion, which the Arabs were eager to spread throughout the region. In the Battle of Yarmouk (636), the Byzantines were defeated by Arab Muslims, who subsequently also took Egypt and Syria.