Introduction

According to United Nations data, the population of Tunisia in 2023 was estimated at 12.458 million, distributed by 49 % of males and 50.7% of females, with a gender ratio of 99 males per 100 females.

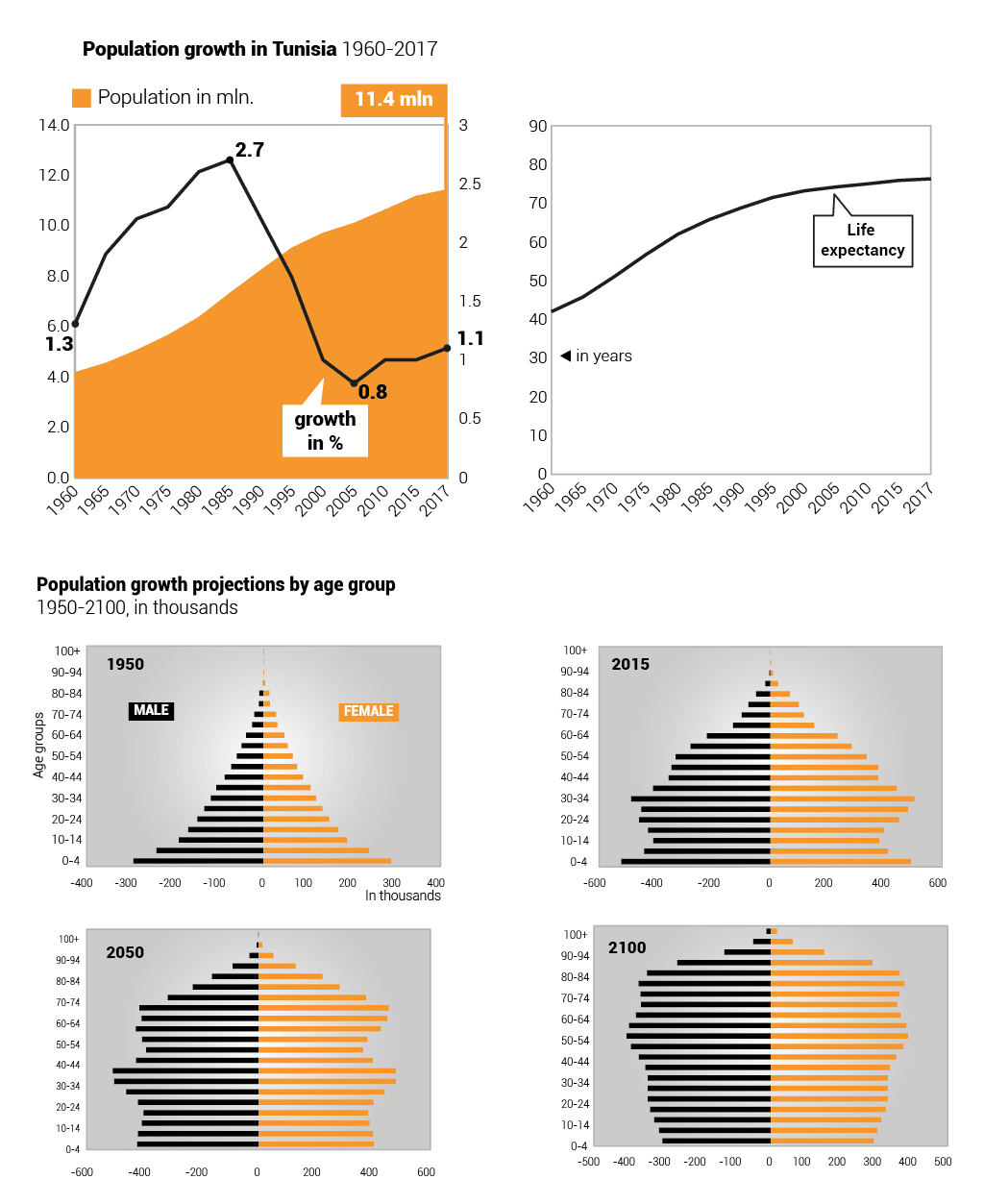

The average annual population growth rate between 2015 and 2020 was 1.12%, and 0.8 % in 2023.

The average annual population growth rate between 2010 and 2017 was 1.2 per cent. This growth rate is considered one of the lowest, due to the decline in fertility rates to 2.2-2.3 births per woman between 2015 and 2020, and 2.1 in 2022.

The last official census in 2014 estimated the population at 10.98 million, made up of 51.1 per cent males compared to 48.9 per cent females. This is an increase of 1.07 million from the 2004 census. The average annual growth rate is 1.1 per cent. The number of families in Tunisia in 2014 was about 2.71 million, with an average size of 4.1 people.

Arabs account for 98 per cent of the population, 1 per cent is European, and the rest are of other ethnic backgrounds. Arabic is the official language and is used in business alongside French, which is spoken by two-thirds of the population, according to the CIA’s World Factbook.

Islam is the official religion, and Sunni Islam represents 99.1% of the country’s total population and less than 1% others (including Christians, Jews, Shiites, and Baha’is).

After President Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali’s overthrow in early 2011, tens of thousands of unemployed Tunisians migrated illegally to Italy and then to France.

Thousands of people who fled the civil war in Libya also joined the convoys trying to reach Europe via Tunisia. However, an agreement to repatriate illegal immigrants signed by Italy and Tunisia in April 2011 helped to reduce the human flows to Europe.

Age Groups

Tunisian society is youthful, despite the decline in fertility rates. More than a quarter of the population (25 %) is under the age of 15, according to the World Bank based on 2023 estimates and ; 66 per cent of the population is aged 15-64. Those who are 65 years old and over make up 9 per cent of the population.

The fertility rate was 2.3 births per woman in 2020, an increase of 0.2 births per woman than 2010. In 2022, the fertility rate was 2.1 births per woman. In 2020, the average life expectancy was 76.45 years (74.4 for males and 78.5 for females), and 74 years in 2022 ( 71 for males and 77 for females).

Areas of Habitation

In 2020, the population density was 76.1 people/km2 and 79 people/ km2 in 2021. According to UN data, urban areas account for 69.3 per cent of the population, and the population growth rate for urban areas stood at 1.53 per cent in 2020 and 1.3 % in 2023.

According to United Nations estimates, in 2020 AD, the capital Tunis ranks first in the country with about 2.328 million people, 19.7% of the country’s total population.

According to the official census in 2014, the state of Tunis accounted for 9.6 per cent of the population, followed by Sfax with 8.7 per cent, Nabeul with 7.2 per cent, Sousse with 6.2 per cent and Ben Arous, Ariana, and Kairouan with 5.8 per cent, 5.3 per cent, and 5.2 per cent respectively.

Ethnic and Religious Groups

The overwhelming majority – approximately 98 percent – of Tunisians are Muslim Arabs or Berbers, most of whom are Sunnis; only a minority are Shiite Muslims. Christians make up about 1 percent of the population, and another 1 percent consists of Jews – who have historically played a significant role in Tunisian society and other small religious and ethnic groups.

The vast majority of the Tunisian people – around 99.1% – are Arab or Berber Muslims, mostly Sunnis. Whereas Shiite Muslims, Christians, and Jews are only a minority.

Sunnis

Most of Tunisia’s population are Sunni Muslims belonging to the Maliki school of Islam, founded by Malik ibn Anas in the 8th century. Still, Tunisia’s Sunnis are far from a homogeneous community. The majority adhere to a moderate interpretation of Islam, which stems from its own Islamic tradition. Early modern thinkers launched important reforms in education, such as Khayr al-Din al-Tunisi (also known as Hayreddin Pasha), who in 1875 founded the prestigious Sadiki College where traditional Islamic subjects were combined with the study of the modern sciences.

Tunisia’s moderate Islamist Ennahda party states that it wants to continue in the tradition of the country’s Islamic legacy. Ennahda’s ideological roots lie in the 1960s Islamic movement called al-Jamaa al-Islamiyya. Having been banned under the regimes of Bourguiba and Ben Ali, Ennahda emerged as the most important player in Tunisian politics after the Tunisian revolution, receiving the bulk of the votes in the October 2011 elections Constituent Assembly.

The persecution and harassment that Ennahda members endured under the earlier regimes and the Islamists’ uncompromising attitude towards those regimes contributed to its perceived legitimacy after the revolution. Whilst rejecting the Western notion of complete gender equality in every field, Ennahda advocates integrating women into social and political life, in contrast to more religiously conservative voices.

Conversely, Tunisia’s leftists comprise Muslims – especially numerous amongst the country’s elite – who are Westernized and liberal, having been influenced by the French legacy and the Bourguiba and Ben Ali regimes’ modernization policies. The left advocates, amongst other policies, complete gender equality and the secularization of the state, although it rejects, for example, rights for homosexuals, as advocated by many Western leftists.

On the other end of the spectrum are Muslims affiliated with the Salafist movement, Islamic militants whose advocacy of a return to the practice of the salaf (the ‘ancestors’ or companions of the Prophet) commits them to a literal interpretation of the Koran and the implementation of the Sharia (Islamic law). Their number is estimated at about 10,000. The Salafist movement can be classified into two divergent streams: the Salafist jihadists and the ‘scientific’ Salafists (the latter focus on Islamic scholarship and preaching and reject the use of violence). Even though most of the ‘scientific’ Salafists are apolitical, some have recently joined the political game by founding the Reform Front Party (Jabhat al-Islah).

A minority within a minority movement, Tunisia’s Salafist jihadists have increased in number since the Tunisian revolution, which has provided the movement, fiercely suppressed under the former regimes, with unprecedented freedoms. In contrast to the ‘scientific’ Salafists, the jihadists consider violence sometimes necessary to achieve their goals. In Tunisia, they are organized primarily through Ansar al-Sharia, a loose jihadist platform with a wide network throughout the region.

Although few, Salafist jihadists have shaken Tunisia’s volatile democracy by their uncompromising and sometimes violent actions: they have stormed an art exhibition in La Marsa that they considered blasphemous; they have set alight the offices of Tunisia’s most important trade union, the Tunisian General Labour Union (Union Générale Tunisienne du Travail, UGTT); and they have ransacked hotels and bars selling alcohol.

In protest of a film mocking the Prophet Muhammad, jihadists have also stormed the US Embassy in Tunis and looted an American school. Most recently, regular criminals have joined the Salafist jihadists’ activities, creating a dangerous mixture threatening the country’s stability.

Shiites

Little is known of Tunisia’s Shiites, and there is no official data on them. Their number is estimated at a dozen to several thousand. The Shiites’ secrecy – most keep their religious affiliation hidden, and some even pray together with Sunni Muslims – make it difficult to obtain reliable information about their numbers. While there are no public places of veneration or Shiite mosques in Tunisia, Gabes’ city is generally considered the Shiite centre of the country. In recent months, some Shiite cultural events have taken place in the city, although the turnout was poor. Mubarak Baadache is the informal leader of the Shiite community in Gabes.

Despite being few and having little public visibility, the Shiites have increasingly come under assault in post-revolutionary Tunisia, with public threats and discrimination occurring daily. In August 2012, for example, Lotfi Bouchnak, a Tunisian singer and public figure, was unable to give a concert in Kairouan as ultraconservative Muslims demonstrated against his companions, an Iranian group Shiites.

The hostile rhetoric foments such anti-Shiite incidents against this Islamic group, including some senior ultraconservative religious figures. Abou Ayadh, for example, the leader of the Ansar al-Sharia branch in Tunisia, openly rejects Shiites as non-Muslims and kuffar (heretics, Sl. kafir) who have no place in Tunisian society.

Sufis

Tunisia is home to a small Sufi community whose exact numbers are unknown. Sufism is a mystical stream of Islam whose adherents worship in how they believe was revealed by Gabriel to Muhammad to come closer to God, thereby purifying themselves. In contrast to orthodox Islam, Sufism in Tunisia has been influenced by Berbers’ religious practices, including their belief in spirits, amulets, and fortune-telling. Holy men (marabouts) propagated the religion, and their tombs are still today visited by pilgrims.

Many Sufis left Tunisia after independence in 1956 because their land and religious establishments reverted to the government at that time. Yet, Sufism has long influenced Tunisian culture deeply, and its presence is still felt today. For example, during Ramadan, Sufi Muslims stage annual festive activities such as dances and music.

Most Sufis consider the city of Nefta, close to the Algerian border, in the region of Bayadha, as their spiritual centre in Tunisia. Throughout the year, pilgrims – attracted by the 100 shrines of marabouts and the more than 24 mosques – visit the city to worship. Since the Tunisian revolution, Sufism has come increasingly under threat, and Salafists have attacked Sufi shrines.

Berbers

There are no statistics on the number of non-Arabized Imazighen, usually referred to as Berbers, presently living in Tunisia. There are some Berber villages in the mountains in the south, whose inhabitants are sometimes known as ‘mountain Berbers.’ Some of the mountain Berbers still live in traditional houses carved out of the mountain rocks. Traditional Berber villages in the country’s south include Matmata, Tamezret, and Zeraoua. Other Berbers live in the south-east, including on the island of Djerba. Nowadays, some Berbers live in large cities, such as Tunis.

Though a quiet and reticent minority, Berbers have come increasingly into the spotlight in recent months, in particular, due to the Salafists’ hostile attitude towards them. For example, a Tunisian Berber association conference, planned for the summer of 2012 in the Matmata region, was canceled in response to threats from ultra-religious Muslims.

Christians

The ruins of the cathedrals from the Roman period testify to the ancient history of Christianity in Tunisia. Sbeitla, in the north of Tunis, was an important Christian city until the Islamic conquest of North Africa. Today, it is one of the most important archaeological sites in the country. The city of Sbeitla was founded in the first century AD, and it became a major Christian center with the collapse of the Roman Empire in the fourth century. The monuments include five churches.

In the fourth century, Saint Augustine (a great Christian philosopher) lived in the Tunisian city of Carthage. He greatly influenced the Christian community in Tunisia and abroad through his philosophical approach to religion. His ideas have also had a great influence on theologians and philosophers to the present day.

Despite the defeat of the Byzantine Empire at the hands of the Arabs in 647, the number of Christians remained large for many centuries. Still, their numbers declined dramatically in the thirteenth century, in the context of what many historians have interpreted as differences and internal conflicts, which caused the migration of Christians abroad.

Thus, the Christians living in present-day Tunisia stem not from indigenous communities but largely from more recent European arrivals, especially during the French protectorate between 1881 and 1956.

The number of Christians in Tunisia in 2018 reached about 30,000, of whom 25,000 were Catholics, and they represent a minority. Still, they are a minority that plays an active role in various educational, social, and economic sectors for historical and cultural reasons. The Catholic Church runs 12 churches, as well as libraries, 9 schools, and 2 clinics. It also organizes cultural events and charitable activities.

The second-largest Christian denomination is Protestants: about two thousand people. Other Christian denominations in Tunisia include The Evangelical Church, a few hundred members; The Church of Reformed France, which has one church and about 140 members; The Russian Orthodox Church, which has two churches and 100 members; And the Greek Orthodox Church, three churches in Djerba, Sousse, and Tunisia, and 30 members.

While the ruling Islamist Ennahda Movement recognized Christian recognition and full support, Muslim extremists’ anti-Christian threats and rhetoric are on the rise after the Tunisian revolution, sparking fear and insecurity among Christians.

Jews

Tunisia has a rich Jewish history. According to Jewish tradition, Jews came to Tunisia for the first time in 586 BCE, following the First Temple’s destruction. Under the Romans and later the Vandals – both relatively tolerant regimes – the Jewish population prospered and increased. This led the African Church councils to issue restrictive laws against Jews, limiting their power and influence.

Also, under the Romans, Jews had to pay a capitation tax of two shekels. Otherwise, however, the Jews were much Romanized; most spoke Latin and had Roman names. In the 6th century, the Byzantines conquered the region that is now Tunisia, the emperor, Justinian, launched a persecution of the Jews that resulted in the Jews being categorized as pagans and Arians.

During the 7th and 8th centuries, the Jewish population of Tunisia increased due to the arrival of Spanish immigrants fleeing persecution by the Visigoth king, Sisebut (d. 620 or 621). Later on, when the Arabs arrived in Tunisia and dominated the region, a wave of Arab Jews from the Levant settled in the Maghreb. Under the imam Idris I, who in 788 proclaimed Mauritania’s independence from Baghdad’s caliphate, some Tunisian Jews initially fought in his army.

But this alliance was short-lived, as many Tunisian Jews refused to attack those Jews in Mauritania who still supported the Baghdad caliphate. Also, they were condemned as humiliating Idris’ treatment of Jewish women.

When the Aghlabid dynasty was established in about 800, following the murder in 791 of Idris I by poisoning, the Jews prospered and gained political and socio-economic influence; in Bizerte, for example, a Jew held the position of governor. The Jewish community in Kairouan particularly enjoyed wealth at that time, but, with the ascent to power of the fourth ruler of the Zirid dynasty al-Muizz ibn Badis in the early 11th century, another wave of persecution began, and all heterodox religions were harassed.

Things became even worse a century later when Abd al-Mumin and his successors of the Almohad dynasty forced Jews and Christians in Tunisia to convert to Islam. Once converted, they were obliged to wear special clothing that identified them because the authorities were not convinced that the new Muslims were genuine converts. The Hafsid dynasty, which ruled Tunisia between 1229 and 1574, led to an improvement in the Jewish community’s living conditions, but discriminatory laws and practices continued.

While there were significant communities in the cities of Kalaa (Algeria), Mehdia (Morocco), Djerba, and Tunis, Jews were, for example, initially prohibited from living within the city of Tunis. Following the victory over Saint Louis of France, who had launched a crusade against Tunis in the 13th century, cities such as Kairouan were proclaimed holy, forcing Jews to move or convert to Islam.

Repression became even more severe in the two subsequent centuries, as illustrated by the complex tax scheme imposed upon the Jewish community. In addition to a general tax that Tunisian Muslims also had to pay, Jews were subject to a capitation tax and a communal tax. Moreover, there was a special annual tax on Jews working in industry or trade.

A group of Italian Jews came to Tunisia at the end of the 17th century and the beginning of the 18th, resulting in two Jewish communities: the immigrants (Grana) and the indigenous Jews (Touansa). As the Granas remained Italian citizens, they held a high legal status and lived in the European quarters. They were therefore not subjected to the humiliations and security threats endured by the Touansas.

With the Ottoman conquest of Tunisia, the security situation of the Touansa community improved. Jews were relatively independent during this time and could profess their religion freely, but they nevertheless had to endure all sorts of indignities. For example, they had to wear special clothes that marked them as Jews, and they were not permitted to ride horses or, when they did ride (on mules, for example), to use a saddle.

With the increasing influence of Europeans in Tunisia beginning in the 18th century, Jews came to enjoy more rights. This improvement can be explained by the European powers’ amelioration of Christians’ status, who were governed by the same laws as Jews at that time. Under Mohammed Bey (ruled 1855–1859), restrictions that had earlier been imposed on Jews, were abolished. Muhammad IIalso promulgated a Pacte Fondamental, a constitution, which lasted until 1864, stipulating for the first time equal rights of all Tunisians, irrespective of creed.

According to paragraph four of the constitution, ‘No manner of duress will be imposed upon our Jewish subjects, forcing them to change their faith, and they will not be hindered in the free observance of their religious rites. Their synagogues will be respected and protected from insult’; paragraph six added, ‘When a criminal court is to pronounce the penalty imposed on a Jew, Jewish assessors shall be attached to the said court.’

Yet, the Pacte Fondamental required Tunisians to pay more taxes and was therefore opposed by most citizens, who lived under harsh economic conditions. The economic instability eventually resulted in a rebellion against the rulers and the abolition of the constitution in 1864, and the status of the Jews declined once again. The late 19th-century invasion by the French, who established a protectorate over the country in 1881, strongly influenced the development of the Jewish community up to the present.

Encouraged by the promise of ‘Liberty, Equality, and Brotherhood,’ many Jews hoped for better living conditions under the French protectorate. They were quick to adopt the French way of life, and many even adopted French citizenship, thereby distancing themselves even further from the Tunisian Muslim majority. Also, French became the mother tongue of many Tunisian Jews who previously spoke Judeo-Arabic. Thus, between 1878 and 1963, 78 of the Jewish newspapers were published in Judeo-Arabic, 65 in French, and only 16 in Hebrew.

With the start of World War II, the French protectorate over Tunisia became enmeshed in what was happening in Europe, including the Holocaust perpetrated by Nazi Germany, and the first law against Jews came to Tunisia in 1940. The laws classified Jews according to their race and set quotas for them in specific professions, such as medicine and the law. In 1940, Tunisia became part of the Vichy regime, with a resultant drastic increase in anti-Semitic laws. In 1942, shortly after the Allied powers arrived in Algeria and Morocco, Tunisia was occupied by the Germans.

Several senior figures in the Jewish community, including its leader, Moises Burgel, were arrested. Under the Nazi occupation, Jews were forced to wear a badge with the Star of David and were subject to fines and property confiscation. They were harassed and persecuted, and more than 5,000 Jews were sent to labour camps, where at least 46 died. Also, 160 Jews were sent from Tunisia to concentration camps in Europe. Before World War II, approximately 100,000 Jews lived in Tunisia, but there are now only about 1,000 left, many having emigrated to Israel over the past decades.

The remaining Jews live primarily in Tunis and Djerba. Both cities have Jewish schools and synagogues. The most important synagogue, al-Ghriba, is in Djerba and has, for many centuries, been the destination of an annual pilgrimage. In 2002, the synagogue was the target of an armed attack claimed by al-Qaeda, which caused the deaths of 21 people, mostly tourists.

Tunisia’s Jews enjoyed the support and protection of former Tunisian presidents Bourguiba and Ben Ali. The leaders of the moderate Islamist Ennahda party, which gained power after the Tunisian Revolution, have reiterated their protection of the country’s remaining Jewish community. Yet, the newly acquired freedoms in Tunisia’s fledgling democracy have resulted in a resurgence of the Salafist movement, including Salafist jihadists, who strongly oppose the Jewish community. The emergence of anti-Israel rhetoric, used by all political parties, has incited anti-Semitic sentiments amongst the population, further jeopardizing the security of the few remaining Jews in Tunisia.