Introduction

Tunisia has a bilingual, multifaceted society. Arabic is the official language, but French is still widely used in business, education, and daily life, especially in the country’s urban centres. Tunisian Arabic is widespread in rural areas, where illiteracy is much higher and many people speak only basic French, or none at all. Tunisian Arabic has been influenced significantly by other languages, especially Berber and French.

Tunisian society has changed greatly since the revolution that ousted President Ben Ali. Islamists, who had been suppressed and often exiled, have become more numerous, and religious symbols, such as the veil, have reappeared. Women play an active part in Tunisian society and enjoy a high level of education, even though they are still under-represented in the workforce.

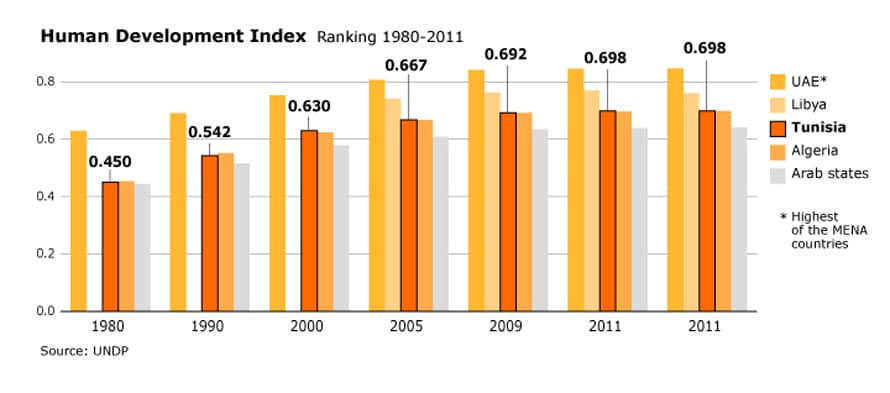

Human Development Index

The Human Development Index (HDI) value for Tunisia in 2011 was 0.698, which ranks the country 94 out of 187 countries and territories in the category of high human development. The average HDI value for countries in this category was 0.7, positioning Tunisia at the lower end of the scale. In the Arab world, Tunisia lies between Libya (64) and Algeria (96). In the period between 1980 and 2011, Tunisia’s HDI value rose on average 1.4 percent per year, for a total increase of 55 percent.

When adjusted for inequality, Tunisia’s HDI score decreases by 25.2 percent, placing the country slightly above the mean loss attributed to inequality in the Arab world, which is 26.4 percent, but below the average 20.5 percent for all countries in the high-human-development category.

Clans and Communities

Tunisian society is not only divided along ethnic and religious lines. Many of Tunisia’s most influential people come from a few large families that dominate the country’s economy and politics. These families are deeply rooted in the history of the country and have created an influential socio-economic and political network over many decades. The members of the well-known Ben Achour family, for example, have for decades held senior positions in Tunisian politics, economy, and academic and religious institutions.

Family Structure

The average household size in Tunisia was 4.7 people in 2007, a gradual decrease from 5.3 in 1990. Traditionally, the Tunisian family household consists of three generations. The youngest generation, however, increasingly follows the Western trend of leaving their family to set up their own household, as a result of work opportunities, increasing income, and a desire for greater independence.

Women are traditionally responsible for child care and the father for the family’s income. However, many women started to work in paid jobs. According to the Tunisian Personal Status Code, the father is the head of the family. In 2007, approximately 13 percent of households were headed by women due to factors such as widowhood and divorce.

Women

The Malikite school of Islam accorded Tunisia a unique legacy in women’s rights. Polygamy, for example, was almost absent long before its official prohibition under Bourguiba. In the city of Kairouan, a stipulation was added to most marriage contracts to the effect that ‘the husband promises voluntarily to his wife to abide by the prohibition, according to the custom of Kairouan’, a city with a long tradition of monogamy. This stipulation, even though it speaks of a ‘voluntary’ promise on the part of the husband, was considered binding de facto. The position of women was further strengthened by another stipulation according to which the first wife could repudiate a second wife and effectively enforce divorce in case her husband breached the monogamy clause. The significance of the monogamy stipulations is illustrated by the fact that, whenever a wife took her husband to court over a breach of that clause, her position was supported by the judiciary in charge.

While such customs and traditions strengthened the role of women in Tunisia’s society, religious traditions and customs nevertheless long undermined women’s effective participation in society. Some modernist thinkers, such as Tahar Haddad, tried to challenge such conservative thinking at the beginning of the 20th century. In 1929 Haddad published several articles in the newspaper al-Sawab advocating women’s judicial and social emancipation, and in 1930, he published a book entitled Our Women in the Sharia and in Society (Imraatna fi al-sharia wa-al-mujtama), which shocked many conservative Muslims in Tunisia. Haddad held that women’s rights are given by God and argued in favour of innovative practices in the fields of marriage and inheritance to enhance the position of women in society. His publications, however, encountered such fierce criticism and so outraged mainstream society and Islamic scholars that he was forced to quit his studies at Tunis’ law school and was eventually forced into exile. With the beginning of Tunisia’s movement of independence from France, some Tunisian women became more active in society, even though the majority remained uneducated and continued to perform the traditional roles of wife and/or daughter. Some urban families began to educate their daughters, who went on to establish women’s associations, although such associations were at that time often exclusive clubs that admitted only the country’s female elite.

During the regimes of Bourguiba and Ben Ali following Tunisia’s independence from France, Habib Bourguiba, the country’s first President, enacted a series of laws to advance the position of women in society. Convinced of the importance of modernizing and secularizing the Tunisian people, Bourguiba sought to integrate women into social and professional life. To that end, he dismantled Tunisia’s religious institutions, such as al-Zaytouna Mosque, which had, until then, dictated the guidelines for the country’s educational system. He created a modern educational system that was accessible to both genders equally, which explains in part why more than 90 percent of women aged 15 to 24 are now literate.

In 1956, Bourguiba enacted Tunisia’s Personal Status Code, a set of laws and principles promoting women’s rights. Most importantly, it for the first time officially prohibited polygamy and repudiation, established a minimum age for marriage, empowered women to seek divorce, and deemed the consent of both man and woman necessary for marriage. Although Tunisia’s Constitution enshrines the principle of equality between men and women, the Personal Status Code still stipulates that the husband is the head of the family. Also, certain provisions, such as the criminalization of marriage between a non-Muslim man and a Muslim woman and unequal inheritance rights, undermine the practice of full gender equality in Tunisia. Tunisia has not signed the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women.

Under President Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali, many secular women’s organizations were created. These organizations also managed to increase somewhat the rights of women in Tunisia. In 1993, for example, they lobbied successfully for a stipulation in the Personal Status Code according to which wives are not obliged to obey to their husbands. In 2007, Ben Ali implemented two laws strengthening the right of housing for mothers who have custody over their children and increased the minimum marriage age to eighteen years for both men and women.

While hailed in the West for its promotion of women’s rights, many of the regime’s gender policies discriminated against conservative Muslims. For example, anti-hijab policies were partially legitimized through Tunisia’s secular women’s associations under Ben Ali, some of which publicly associated the veil with backwardness and berated veiled women. The police often removed the veils of women in public, while law number 108 banned the hijab in state offices and educational establishments. Religiously conservative women were therefore largely excluded from the benefits of earlier gender policies.

Because of the persistence of conservative values and the lack of full gender equality, many women perform traditional roles despite having received an education. Thus, while women comprise almost 60 percent of students enrolled in Tunisia’s higher-education system, they constitute only about 27 percent of the workforce. This indicates that pressure to perform the traditional roles of wife and mother still prevents many women from working. Some government regulations make it more difficult for women to find work: mothers working in private industry, for example, are granted only 30 days’ paternity leave, making it difficult for many to combine work with family life.

After the revolution and with the ascent of Tunisia’s moderate Islamist Ennahda party, many secular women fear that their achievements and rights enacted under earlier regimes are threatened. Such fears were realized when the ruling party proposed an article in the Constitution under which ‘The state guarantees the protection of women’s rights and consolidation of [past] gains based on women being fundamental partners to men in nation-building, with their roles complementing one another within the family’. Such a stipulation of complementary gender roles would undercut earlier references, especially in Tunisia’s Personal Status Code, to equality between men and women, as the Personal Status Code is subordinate to the Constitution. The precise meaning of ‘complementarity’ is also subject to interpretation and hence to arbitrary application. From a secular point of view, such an article would consequently threaten women’s status and their role in the family and society.

Ennahda’s moderate Islamists, including women, justify the reference to ‘complementarity’, saying that this does not mean that women are inferior to men but only that they are different and hence have different roles in life. According to Ennahda, men and women are equal in dignity but should not enjoy equal rights in every aspect of life, as they do in Western societies: men should have more rights in some areas and women in others. Ennahda holds that, even though the family is a woman’s primary responsibility, women can also be active in society and politics, noting that a women was appointed to the position of vice-president of Tunisia’s Constituent Assembly, the highest position held by a women in the Arab world.

Ennahda thereby differentiates itself clearly from Tunisia’s religiously more conservative minority Salafists, who advocate a full separation of the sexes in the public sphere and who disagree with many aspects of Tunisia’s Personal Status Code, such as the prohibition of polygamy and the equal role it prescribes for men and women.

Youth

Tunisia has a young population, who are an active but increasingly volatile social group. Unemployment is high amongst the youth of Tunisia, and many of Tunisia’s youth suffer from economic hardship and accompanying political disillusionment. The situation is particularly frustrating for young Tunisians because their level of education is high by regional standards, but many university students find themselves without jobs or prospects upon graduation.

Given their high level of education and political awareness, young people formed an integral part of – and perhaps the driving force behind – the Tunisian revolution. The country has many young bloggers and Internet users who organized nationwide protests through social-media sites, most importantly Facebook and Twitter, in December 2010 and January 2011. Since the Tunisian revolution, many young people have been disappointed by continuing economic hardship and what they see as government infringement on press freedom and personal liberty.

Education

Tunisia’s education system has its roots in the French system. Basic education involves six years of primary education, after which students must take an exam to proceed to three years of preparatory education. At the end of the three years, a nationwide exam leading to the Diplôme de Fin d’Etudes de l’Enseignement de Base determines which students will be allowed to proceed to secondary education. Those students enrolled in secondary education – 466,939 students during the academic year 2010-2011 – specialize, after a year of general studies, in economics, management, sciences, or languages. After four years, they take the nationwide Baccalauréat examination. More girls than boys are enrolled in both primary and secondary education.

Due in part to an increasingly young population and in part to a better education system, more than three times as many students have enrolled in Tunisia’s higher-education system over the past decade. During the academic year 2010-2011, Tunisia’s National Institute for Statistics counted 85,705 new first-year university enrolments. Tunisia has thirteen universities and almost 200 other higher-education institutes. During the academic year 2010-2011, almost 62 percent of enrolled students were female. During the academic year 2009-2010, 32,317 men and 53,718 women graduated. The greatest number of students graduate from computer and telecommunication sciences, followed by arts and human sciences.

Although Tunisia has a high rate of university enrolment, the country struggles to integrate its young graduates into the labour market. Indeed, unemployment amongst educated youth is high, revealing a mismatch between educational standards and the demands of the labour market. As the number of graduates continues to increase, the government must find a way to integrate educated youth into the labour market in order to counter mounting economic frustration and political disillusionment.

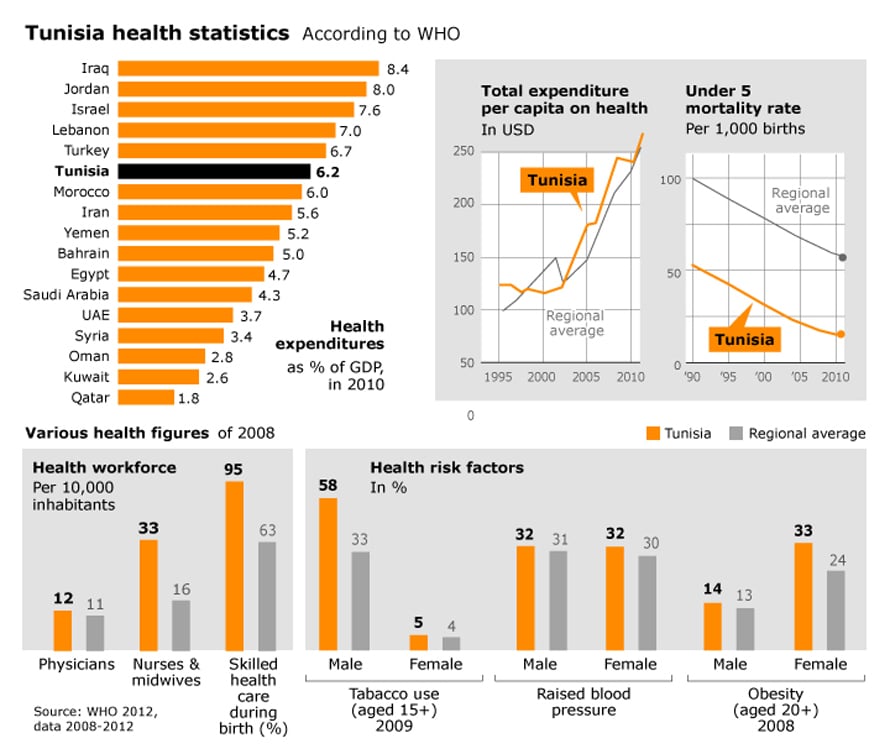

Health

The World Health Organization’s 2008-2013 Tunisia Country Cooperation Strategy states that Tunisia has improved his health-care system over the past years, despite the country’s limited material resources. This has led to a generally effective system, with the public sector accounting for 90 percent of hospitalizations in basic health-care facilities. The number of communicable diseases, such as polio, and neonatal tetanus is either at a low level or has been decreasing constantly over recent years. The number of registered HIV/AIDS cases has risen slightly. In response to maternal- and child-health programmes, the number of maternal and infant deaths has decreased substantially. Due to regional disparities, however, maternal and child health continue poor in underdeveloped rural regions, in particular in Tunisia’s west and south. Some non-communicable diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, cancer, and injuries, are on the rise.

The death rate from hypertension is 11.3 percent among women and 6.4 percent among men. Diabetes accounts for 8.1 percent of deaths in women and 5.7 percent in men. Closely linked to diabetes, obesity and overweight are a greater problem for women (62.5 percent) than for men. Another main cause of death in women is stroke. For men, death is frequently caused by ischaemic heart disease (6.6 percent, compared with 3.4 percent for women), traffic accidents (6.2 percent, compared with 1.6 percent for women), and lung cancer (5.2 percent, compared with 0.6 percent for women). The high rate of lung cancer in men is due mostly to their high rate of smoking, estimated at 52.8 percent; only about 5.2 percent of women smoke.

According to a 2008 WHO-AIMS Report, Tunisia’s mental-health system faces persistent challenges, in part because no specific budget is allocated to mental hospitals, resulting in insufficient mental-health investment. Mental-health services are almost absent from rural and underdeveloped areas; most services are limited to Tunis and Tunisia’s coastal cities. There is also a shortage in psychologists and social workers qualified to provide mental-health services.

For years, mental health remained taboo, but Tunisians seem now to be increasingly open to it, and that facilitates treatment.

Crime

The US Department of State classifies Tunisia as posing a medium threat of crime. Tourist areas particularly are at risk from thieves targeting purses and other valuable items. Vehicle break-ins and fraud are also threats, especially for tourists and people that seem unfamiliar with the area. Theft of vehicles is comparatively rare. Thieves are most often male; they sometimes attack people walking on the street from motor scooters. Religiously motivated violence has increased in de post-revolutionary period, jeopardizing the internal stability and security.

President Ben Ali’s treaures exposed

Former president Ben Ali’s hidden safes in his palace, loaded with stacks of cash money in various currencies and jewelry was opened and shown, live on Tunisian television (Youtube)

Latest Articles

Below are the latest articles by acclaimed journalists and academics concerning the topic ‘Society’ and ‘Tunisia’. These articles are posted in this country file or elsewhere on our website: