Introduction

The World Economic Forum declared Tunisia in 2011-2012 the most economically competitive country in Africa and number 40 globally. The West had long praised its economic liberalization program, citing it as a model for the whole region. Over the past decade, Tunisia’s sustained economic growth has been pointed to by many outside observers, including the European Union.

Still, the fact that such growth had not resulted in improved living conditions has largely been ignored by most people. Poverty and unemployment in Tunisia have soared over the past decade, especially among the young and rural areas. Such economic hardship was a major cause of the uprisings that erupted in Tunisia in December 2010 and finally led to President Ben Ali’s ouster. The promotion of inclusive economic growth remains a primary challenge in Tunisia.

According to the World Bank, despite making significant progress on the political front, Tunisia’s economic gains will require time. The national unity government, which was formed in September 2016, has prioritized security, improving the business environment, and accelerating the creation of good-quality jobs – a potential boon for university graduates, around 30 percent of whom are unemployed.

The World Bank predicts that economic growth will improve in 2018 and 2019 as the business climate improves, structural reforms are implemented, and security and social stability increase. However, it warns that widespread corruption, a lack of competition, and stagnating productivity pose an ongoing challenge.

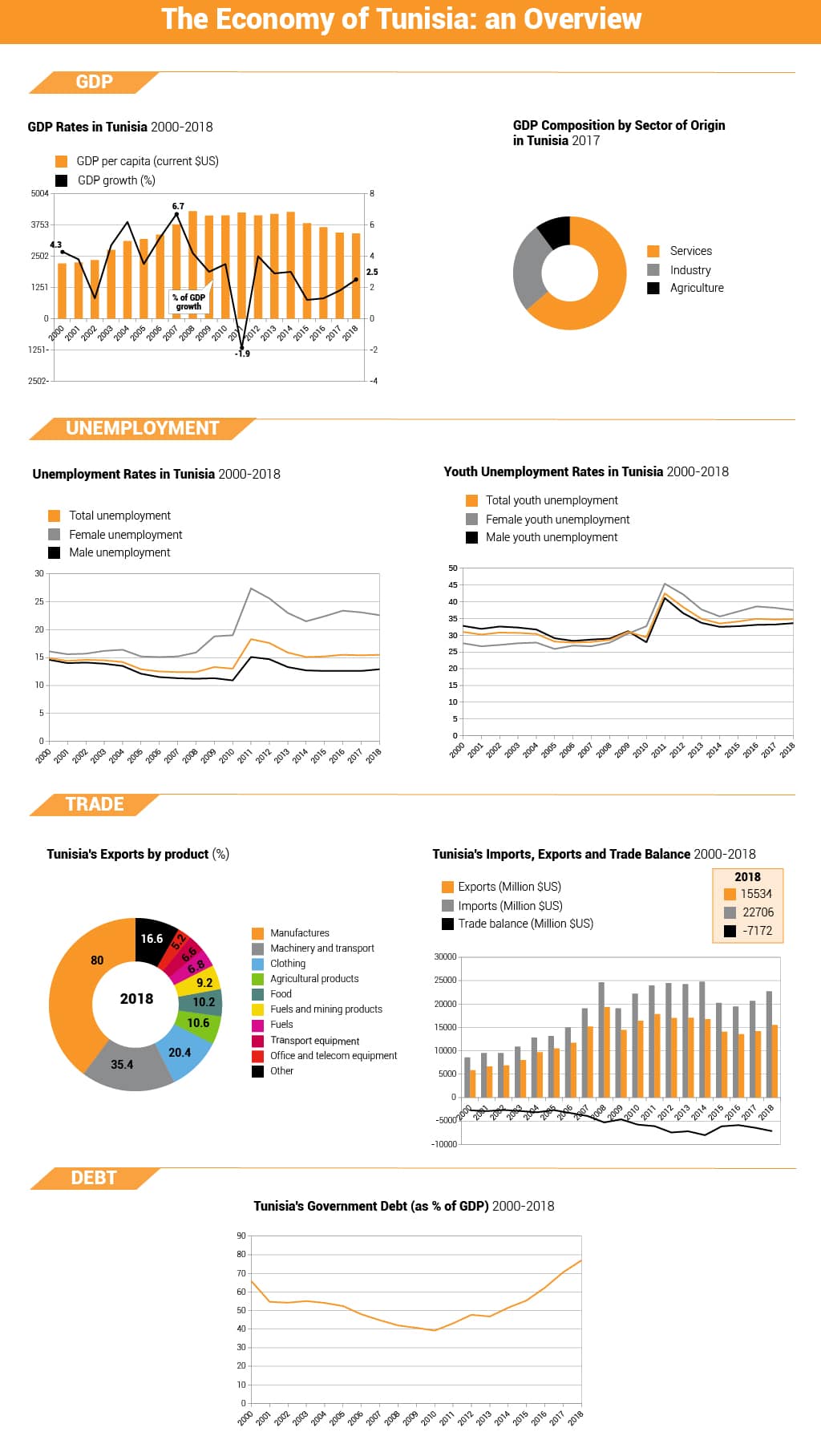

Gross domestic product (GDP) in 2015 was $43 billion, compared with $47.6 billion in 2014 and $46.2 billion in 2013. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) predicts that GDP in 2017 will grow by 2.8 percent, compared with 1.5 percent in 2016 and 0.8 percent in 2015. GDP per capita in 2015 was $3,923. In 2017 is expected to be 3.9 percent, compared with 3.7 percent in 2016 and 4.9 percent in 2015.

Tunisia ranked 95th in the Global Competitiveness Report 2016-2017, down three places from 2015-2016.

Tunisia’s economic growth rose slightly to 2.5 percent in 2018 from 2 percent in 2017, supported by agriculture and the service sectors (including tourism, which saw a significant rebound) and the mechanical and electrical industries. On the demand side, growth was driven again by higher exports and investment.

At the same time, private consumption shrank, according to the World Bank, which expected growth to average 3 percent in 2019/2020 and to reach its potential of about 4 percent in the medium term, provided that reforms to improve the investment climate, security situation and social stability are completed. Growth will also be boosted by the start of production from the Nawara gas field in mid-2019.

The poverty rate is expected to remain unchanged at around 3 percent, using the poverty line of $3.20 per person per day (2011 purchasing power parity), and less than 1 percent using the extreme poverty line of $1.90.

Gross Domestic Product

After economic growth recorded a slight recovery of about 2 per cent in 2017, it accelerated to 2.5 per cent in the first quarter of 2018 and 2.8 per cent in the second quarter, supported by agriculture, tourism and the mechanical and electrical industries.

On the demand side, growth was driven by exports and investments.

The unemployment rate remained high at 15.4 percent in the first quarter of 2018 but fell slightly among graduates to 29.3 percent compared to the fourth quarter of 2017 when it reached 29.9 percent.

The World Bank predicted that the growth rate would reach 2.4 percent in 2018 before gradually approaching its potential of about 3.4 percent in the medium term for the same year as the business climate improves due to structural reforms and improved security and social stability.

Growth will be supported by expansion in agriculture, the transformative industries and tourism-related services.

| Indicators | measuring unit | 2016 | 2017 | Change ± |

| GDP (at constant 2010) | Billion US$ | 48.682 | 49.634 | 0.952 |

| GDP growth (annual) | % | 1.1 | 2.0 | 0.9 |

| GDP per capita (constant 2010) | US$ | 4,269 | 4,304 | 35 |

| GDP (at current value) | Billion US$ | 41.808 | 39.952 | -1.856 |

Source: World Bank.

International Market Position

Tunisia was ranked 95th out of 137 countries covered by the Global Competitiveness Index 2017-2018, the same position as 2016-2017. Its performance has remained stagnant over the past years, with no significant movement since the end of the political crisis in 2014. The lack of improved labor market efficiency remains the primary reform priority, an area where the country has continued to decline in recent years and now ranks 135th globally.

The macroeconomic environment remains challenging, with a decline in gross national savings (13.1 per cent), a raise in the general budget deficit (5.7 per cent of gross domestic product) and an increase in debt (60.6 per cent of gross domestic product). According to the Global Competitiveness, the performance of the country’s markets is hampered by high tax rates (60.2 per cent of business profits in 2016), as well as inadequate trade integration, constrained by both non-tariff barriers (119) and customs procedures (122).

The quality of institutions has slowly improved, but inefficient government bureaucracy, corruption and political instability remain among the three most problematic issues facing businesses in the country. Technological readiness is the biggest improvement since 2013, and Tunisia is the country using the most information and communications technology in North Africa (81st globally).

| Indicator | Rank (out of 138) 2016–2017 | Rank (out of 137) 2017–2018 | Change in rank ± |

| Institutions | 78 | 80 | -2 |

| Infrastructure | 83 | 82 | 1 |

| Macroeconomic environment | 99 | 109 | -10 |

| Health and primary education | 59 | 58 | 1 |

| Higher education and training | 93 | 82 | 11 |

| Goods market efficiency | 113 | 112 | 1 |

| Labor market efficiency | 133 | 135 | -2 |

| Financial market development | 119 | 110 | 9 |

| Technological readiness | 80 | 85 | -5 |

| Market size | 69 | 69 | 0 |

| Business sophistication | 101 | 98 | 3 |

| Innovation | 104 | 99 | 5 |

| Global Competitiveness Index | 95 | 95 | 0 |

Source: Global Competitiveness Index 2016/2017 and 2017/2018.

Industry

Tunisia’s industrial sector consists of more than 5,700 enterprises, most of which are approximately 34 percent, manufacture textile and wear apparel. Another 18 percent manufacture food products.

Almost 523,000 people are employed by industrial enterprises with 10 or more employees; the textile and clothing sector (ITH) accounts for almost 37 percent, followed by the food industry (IAA), accounting for almost 14 percent.

Construction

Construction provides direct jobs for more than 2,000 people and indirect jobs for more than 7,000. Especially since the Tunisian revolution, the smuggling of construction steel, particularly from neighboring Algeria, has increased, damaging the sector’s profitability. Thus, while about 485,000 tonnes of construction steel were sold in Tunisia in 2010, the amount decreased in 2011 to 428,000 tons, dropping 16.5 percent. In the first half of 2012, the amount of construction steel sold decreased by almost 40 percent.

Regional development

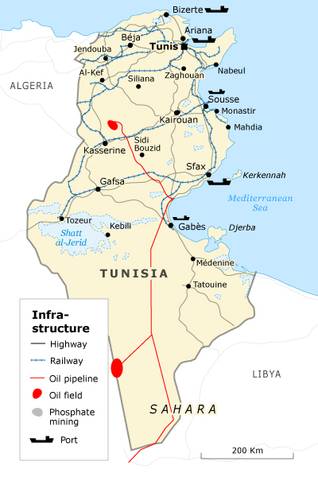

Tunisia’s industrial firms are located around main urban areas, with the coastal cities hosting most economic activity. These regions receive 65 percent of public investment, while Tunisia’s hinterlands are underdeveloped and suffer economically.

Places such as Jendouba, Tozeur, Gafsa, and Sidi Bouzid, where the Arab uprising began, have been hit particularly hard by inadequate infrastructure and economic opportunities, resulting in unemployment widespread poverty, especially amongst vulnerable groups such as women and the youth.

Agriculture

Tunisia’s agricultural sector has grown steadily in both output and investment. Agriculture is Tunisia’s most important primary industry, accounting for approximately 14 percent of GDP. Almost 20 percent of the country’s total workforce is employed in agriculture.

The main agricultural products include olives and olive oil, tomatoes, grain, citrus fruit, dates, sugar beets, dairy products, and almonds. According to Tunisia’s Agricultural Investment Promotion Agency, the agricultural sector attracted during 2011 – a challenging year for Tunisia’s economy, due to the political turmoil surrounding the overthrow of the Ben Ali regime – almost USD 307.5 in investment, and investment in the sector in 2012 will probably increase still further.

Tunisia exports large amounts of its agricultural products to Europe, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia. Agricultural products represent around 14 percent of Tunisia’s total exports. Tunis Afrique Presse reported that over 14,000 tonnes of agricultural produce were exported during the 2012 growing season, an increase of 17 percent over 2011.

To make Tunisia’s agriculture sector more attractive, the government has launched promotions to attract foreign investors and enhance strategic partnerships with other countries in the region. In October 2012, Tunisia hosted the International Exhibition for Agricultural Investment and Technology, and, at the end of 2012, the Arab Organization for Agricultural Development held its annual meeting in Tunisia.

According to a report by the African Development Bank, Tunisia must implement various agricultural-policy reforms to gain maximum profit from the sector. Reforms should address issues such as price controls, protectionism, farming standards, and crop yields. More investment in rural agriculture is necessary for modernization, especially in food marketing and processing.

Banking

Although Tunisia launched an economic reform programme that stipulated liberalization and privatization, reforms in the banking sector have been limited. The government controls the three largest public banks, and state-owned banks make up more than 50 percent of the market. Following the Tunisian revolution, those banks owned by the Ben Ali family were taken over by the central bank. Since the head of the Tunisian Central Bank was fired in June 2012 by President Moncef Marzouki, the independence of the institution has come under increasing threat.

Since the Ben Ali regime’s fall, steps towards an offshore banking system have been taken to boost Tunisia’s economy. Islamic banking, primarily through the country’s Zitouna Bank, is also encouraged by the new government’s new government, the moderate Islamist Ennahda party. However, the banking sector has undermined real growth by making bad loans, increasing capital costs, and creating an inefficient resource-allocation system. High levels of nonperforming loans also remain a significant problem; they continue to account for approximately 12 percent of all loans, compared with 4.8 percent in Morocco, for example.

Informal Sector

Illegal tank station near Sousse / Photo ShutterstockAn estimated 35 percent to 42 percent of the Tunisian labor force works in the informal sector, including half of the country’s unemployed. The informal sector accounts for approximately half of Tunisia’s GDP. The most frequent sort of informal work in Tunisia is in small street shops. According to Tunisia’s National Institute for Statistics, about 490,000 of an estimated 520,000 informal sector workers earn money through such illegal shops. The state can theoretically fine but, in practice, usually tolerates. Another significant informal work category is domestic economic activities, such as handicrafts, and domestic services such as cooking and cleaning.

Cross-border smuggling is another common kind of informal work in Tunisia. Smuggled goods frequently come from neighboring Libya or Algeria, where many goods’ prices are considerably lower, making their sale on the Tunisian market lucrative, if illegal. Many Tunisians work at various illegal repair or towing jobs, and some work informally in flea markets.

Infrastructure

The Ben Ali government began in the mid-1990s to increase investment in infrastructure. The 2011-2012 World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Report ranked Tunisia 43 out of 142 in the quality of the country’s infrastructure.

Telecommunications: one of Tunisia’s most promising sectors, telecommunications have enjoyed high, sustained growth in recent years, reaching 15 percent in 2009. Between 2001 and 2006, more than 5 million dinars were invested in the telecommunications sector, and investment increased to over 6 million dinars between 2007 and 2011.

Transport: Tunisia has 20,000 kilometers of paved roads and 360 kilometers of dual carriageways. It has nine international airports (Tunis, Djerba, Monastir, Enfidha, Tabarka, Tozeur, Sfax, Gabes, and Gafsa). There are 2,167 kilometers of railways and seven commercial ports, and an eighth port is under construction.

Industrial zones: more than one hundred.

Economic-activity parks: Zarzis-Djerba and Bizerte both host economic-activity parks.

Information and communications technology: the 2010-2011 World Economic Forum’s Global Report on ICT ranked Tunisia first in Africa and 35th globally.

Tourism

Tourists on camels in the Tunisian desert /Photo ShutterstockTourism is a mainstay of the Tunisian economy, with a value of around 2.5 billion USD. More than 400,000 people (out of a total of about 10 million) work in tourism. Tourism suffered greatly in 2011 due to Tunisia’s social unrest and political turmoil. Although the tourism industry’s performance improved slightly in 2012, there is still a lack of tourists, resulting in fewer jobs and the closing of many hotels.

Important tourist destinations include Tunis, Carthage, Hammamet, Sousse, and the island of Djerba, in the south. Important tourist markets are France, Germany, the United Kingdom, and Italy, countries well connected to Tunisia through low-priced airlines.

Workforce and Labour Migration

Continuous protests against the economic crisis shake the country, 27 November 2013, Gafsa, Tunisia Photo Corbis.The workforce-activity rate for men in 2010 was almost 70 percent but only about 25 percent for women. Although women enjoy a high education level, traditional gender roles still dominate in the Tunisian work environment. Men and women are increasingly moving into urban centers, especially greater Tunis and Ben Arous, Sousse, and Monastir’s coastal cities to find work. With opportunities limited in Tunisia and unemployment worsening, some people try their luck in neighboring countries such as Libya, which enjoys close economic ties with Tunisia.

Tunisia’s faltering economy was one of the major contributing factors to the 2011 revolution, and in the years since the revolution, it has continued to deteriorate. Closely tied to the eurozone (around 80% of Tunisia’s trade is linked to Europe), the economy keenly felt the euro crisis’s effects from 2008 onwards. Moreover, the high number of university graduates, which number 80,000 per year out of a population of just over 10 million, has exacerbated unemployment. The unstable security situation in Libya, Tunisia’s second economic partner, has added insult to injury.

Unemployment is at 15.3%, with that figure even higher among young people and women. Economic growth at the end of 2014 was just 2.4%, almost 4% below what is needed to curb unemployment. Tunisians deeply resent the 5.5% inflation rate and unfavorably compare commodity prices to their pre-revolution levels. The Tunisian dinar (TND) has lost more than 20% of its value since 2010, with 1 TND now worth around $2, and the country’s international debt had climbed from 40.7% in 2010 to 52.9% in 2014.

The worsening economic conditions have directly contributed to growing disillusionment among the Tunisian public with the revolution’s outcomes, despite its political successes, and has led to some yearning for a return to the old regime. All the political parties that ran in the October 2014 parliamentary elections against the winners of 2011 stressed the economy to seduce voters. The secularist Nidaa Tounes party, for instance, had an electoral banner showing a shopping bag in a popular market with the words “Temporary Dearness,” meaning that commodity prices would go back to their pre-2011 levels if they won. The banner was also a clear political jibe: “Temporary” is the nickname for the troika government of the Ennahda, CPR, and Ettakatol parties.

Although the plummeting oil prices in 2014 were expected to help shore up the Tunisian economy, rampant corruption in the energy sector and the declining security situation in Libya (Tunisia’s key oil supplier) meant any benefits were negligible. Drivers filling up at a petrol station still pay more for fuel than they did a year ago.

Tourism revenues, which are crucial to the Tunisian economy (6.5% of GDP and around 350,000 jobs), have almost returned to their 2010 levels. European tourists, whose tour operators redirected to struggling European countries such as Greece and Spain or have avoided Tunisia since the start of the Arab Spring, have largely been replaced by Algerian and Libyan tourists.

European tourists are preferred to their Arab counterparts, however, as they enhance Tunisia’s international appeal. They also bring a strong currency (euro) and are willing to buy traditional items, such as chechia headgear and jebba tunics, which are of little interest to most Arab tourists. There is widespread concern that the March 2015 terrorist attack on Tunis’ Bardo Museum, which killed 21 people, including 17 tourists, will further hurt foreign tourism.

There is also a fear that Libya’s declining security situation will impact disposable incomes in that country, making holidays across the Tunisian border an unaffordable luxury. Coupled with this is the concern that the growing number of Libyan refugees in Tunisia could become a drain on the economy as their financial resources dwindle. Still, they continue to consume Tunisia’s subsidized goods (bread, oil, and so on) and push up real estate prices.

Since the revolution, people have become less respectful of state authority, seen as a remnant of the dictatorial regime. With waning state bureaucracy in Tunisia and Libya’s quasi-collapse, informal trade across Tunisia’s land borders has expanded considerably. Estimates indicate that informal trade now accounts for around 40% of Tunisia’s economy, depriving the state of significant tax revenues and diminishing its control over the foreign currency. This has accelerated Tunisia’s tumble in international credit ratings (Moody’s, Standard & Poor’s) and tarnished its pre-2011 image as “the model pupil of the international institutions.”

In the face of this economic decline, the Tunisian government is likely to adopt unpopular measures advocated by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. These include cutting subsidies, reducing the number of public-sector jobs, crushing informal trade, and the sine-qua-non conditions for receiving those institutions’ loans and grants. The USA, one of Tunisia’s main sponsors after the revolution, is also pushing for reforms, particularly of the judicial system, before it agrees to invest in Tunisia.

Government officials are reluctant to announce the measures publicly but rely on allusions and gradual change. This has not stopped the spread of social movements. These are co-opted by UGTT, the leftist trade union, which is known for its oppositional stance and broad power base.

Demonstrations and strikes are legion, affecting offices and factories’ productivity and contributing to the country’s general economic malaise. Local and international investors have threatened to withdraw from Tunisia if the movements continue at their current pace, but their threats have so far been ignored.

Leftist movements such as the Popular Front, and populist ones such as former President Moncef Marzouki’s Citizen People Movement, will spearhead the opposition to these measures, as Syriza has done in Greece or Podemos in Spain. The extent of their success remains to be seen. Economic indicators show that the country is fragile, with the looming specter of a return to authoritarian rule or a second revolution.

Poverty

The latest poverty figures are from 2015, when the Tunisian National Institute of Statistics (INS) published a new series of poverty rates based on consumption patterns observed in the Household Budget and Living Conditions Survey. According to these figures, the poverty rate was 15.2 percent, well below the 20.5 percent rate in 2010 and 23.1 percent in 2005.

Similarly, when measured using the international poverty lines of $1.90 and $3.20 a day (2011 purchasing power parity, PPP), it has also sharply decreased. Using the poverty rate of $1.90 PPP, poverty was almost eliminated in 2015 (less than 1 percent), while using the poverty line of $3.20 PPP, it decreased to 3.2 percent from 9 percent in 2010.

Poverty is usually concentrated in the north-western regions (28.4 percent) and the midwest (30.8 percent). The poverty rate in the northern coastal areas is 11.6 percent, 11.4 percent in the central region, and 5.3 percent in the Grand Tunis metropolitan area. However, there are pockets of relatively high poverty in the latter.

However, inequality took a downward path in 2005. According to official figures, the Gini index was 36 in 2005 and fell to 33.9 in 2010 and 32.8 in 2015. In October 2018, the World Bank predicted that the poverty rate would remain unchanged at 8.7 per cent, using the poverty line of $3.20 PPP, and about $1.90 using the poverty line of $1.90 PPP.

| Indicators | Number of Poor (thousand) 2015 | Rate (%) 2015 |

| National Poverty Line | 1,713.6 | 15.2 |

| International Poverty Line 1.6 in Tunisian dinar (2015) or US$1.90 (2011 PPP) per day per capita | 29.4 | 0.3 |

| Lower Middle Income Class Poverty Line 2.8 in Tunisian dinar (2015) or US$3.20 (2011 PPP) per day per capita | 361.8 | 3.2 |

| Upper Middle Income Class Poverty Line 4.8 in Tunisian dinar (2015) or US$5.50 (2011 PPP) per day per capita | 2,065.3 | 18.3 |

Source: The World Bank.

Latest Articles

Below are the latest articles by acclaimed journalists and academics concerning the topic ‘Economy’ and ‘Tunisia’. These articles are posted in this country file or elsewhere on our website: