Youssef Sharqawi

Introduction

The Hamama Tribe is one of the biggest tribes residing in Tunisia. However, their origins and when they settled there remain a mystery.

Neither medieval historians like Ibn Khaldun nor 16th and 17th centuries historians made mention of the tribe. And so, a mystery envelops this central tribe’s modern historical features, as Mustapha Tlili described in the preface of his book al-Mahal’a wa al-Hamama.

Origins

The name Hamama was given to the tribe by the first great-grandfather: Hammam. While sources agree that the tribe descended from Arab origins, researchers’ opinions differ on whether it descended from Banu Hilal or Banu Sulaym. It is not ruled out that some of the tribe’s branches mingled with Amazigh groups.

Some narratives ascertain that the first great-grandfather, Hammam, had two sons, Rabe’a and Idris, from which the tribe branches descended. While the Awlad Radwan tribe descended from Idris’ lineage, Awlad Muammar and Awlad Aziz tribes are part of Rabe’a’s lineage.

Tribal belonging and loyalty in Tunisia do not stem from a single origin, as they usually do in the Arab Mashriq. They are governed by nature and surrounding conditions. Pressures from wars, famines and tribal disputes have led some branches to split from their mother tribes to form a separate body and thereby become another central tribe.

According to the Encyclopedia of Tribes and Nobles in Ancient and Modern Tunisia – Mu’jam al-Qabae’l wa al-Ashraf, the Hamama tribe resides in Gafsa and Sisi Bouzid in southwest Tunisia. Additionally, some branches can be found in the city of Meknassy in mid-Tunisia.

Adventurous Spirit

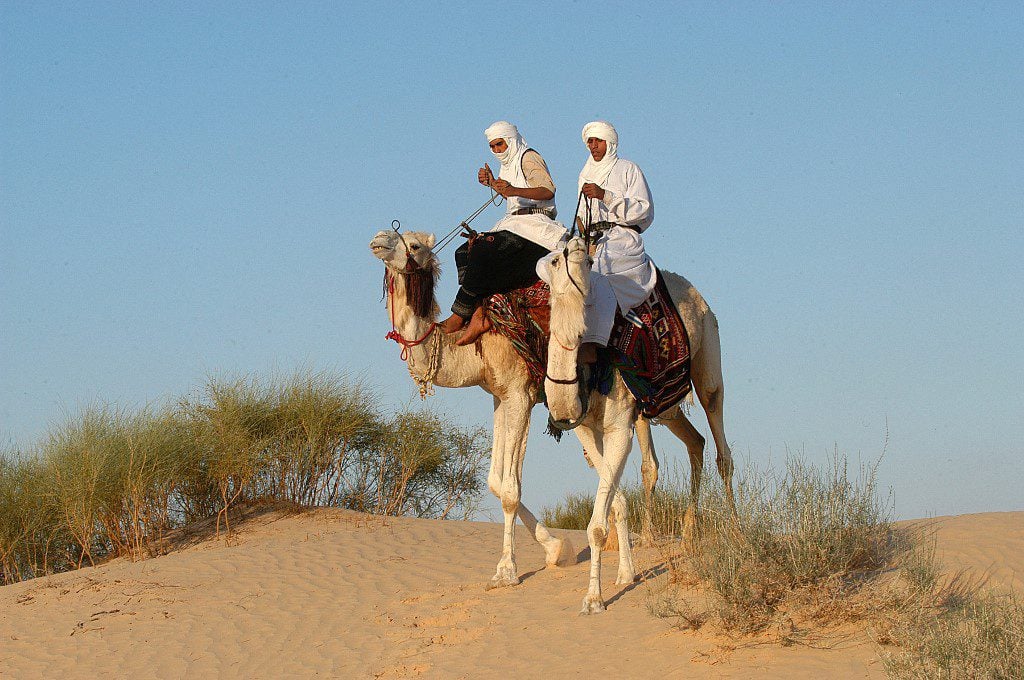

The Hamama tribe was an annoying neighbour to surrounding tribes, as its members are well-known for their love of conquest and adventures. Their identity is closely related to an old Arab proverb; “A saddle, bridle and living for Islam.” Tradition has it that mothers whisper these words into their newborns’ ears.

As such, it can be said that the Hamamian life is based on horsemanship and adherence to Islamic teachings. Reportedly, the tribe’s members provide horses and weapons for their children in their quest for adventure. Children who return from their ventures with exceptional gains are considered real Hamamians.

Horsemanship is one of the Hamama tribe’s most well-known skills and is widespread among its members owing to the tribe’s historical identity. For centuries, the tribe was one of Tunisia’s most powerful, which prompted the Beys of Tunisia to make use of the Hamama’s knights in internal and external wars.

The tribe was known for its role in resisting French colonisation after the Bardo Treaty. Mohamed Ali Habachi’s book Orosh Tunis – Thrones of Tunisia mentions a message from Awlad Muammar’s leader to the prime minister in which he said,

We are the Hamama, servants of the late Sidi Hussien bin Ali. May god rest his soul and bless his descendants and preserve them. The throne belongs to us as they are our ancestors, and we are their descendants, and we don’t want their throne to be defiled by others than them, and shame would haunt us across the country if we do not resist the French.

It is challenging to talk about the Hamama society today. Since Tunisia’s independence, tribal structures have regressed in favour of the national state.

Over time, this regression has reduced the privacy and autonomy of tribal societies while national societal characteristics have expanded, as Amin al-Harshani, one of the tribe’s members, told Fanack. “It is more accurate today to talk about a geographical space featuring some cultural peculiarities, given that most of that space’s inhabitants descend from the same tribal origins, just like the Hamama tribe,” he added.

Righteous Awliya

Despite modernity, the regions where Hamama members reside have maintained some of their traditions. Among the most prominent traditions is celebrating the righteous Awliya and their shrines. The Awliya are those that have been truly pious and God-fearing and are, therefore, role models to others.

These annual celebrations are called ‘Zarda.’ Zarda is a “folklore carnival held around the shrines of the Awliya and is linked to spirituality and inherited beliefs regarding the Awliya’s powers to deter dangers, fulfil wishes and increase devotion to God.”

Mehdi Mabrouk, the former Tunisian Minister of Culture, thinks Zarda is a part of Islam and the popular Sufi belief. As reformist religious movements emerged and these practices were banned under the pressure of Wahhabism, the phenomenon diminished during the 17th and 18th centuries throughout the Arab Mashriq. According to Mabrouk, Zarda remained strongly present in the Arab Maghreb countries.

Al-Harshani says, “The existence of shrines led to the organisation of annual celebrations to celebrate these pious Awliya. These celebrations include several cultural activities, such as horsemanship, bedouin songs, and reciting local Sufi supplications.”

Weddings

The Hamama’s weddings are typically held over the course of several days. According to al-Harshani, the day of documenting the marriage is the day of ‘Mi’aad,’ which is followed by three wedding days.

The first day is the ‘Kiswah’ day, during which the groom’s family presents gifts and trousseaus. Gifts are presented in daytime women’s gatherings on the melodies of folklore music. A nighttime henna ceremony ensues and is one of the most notable features of Hamamian weddings. The marriage then ends on the wedding night.

“People usually offer large quantities of food adhering to their bedouin traditions,” says al-Harshani. He adds that “tradition has it that couscous with lamb and mutton is served as a main dish for everyone to share.”

Hamamian cuisine is not very diverse. Like most bedouin tribes, they mainly eat lamb, which is also commonly served at weddings or funerals. “Hamamians often cook lambs according to a recipe they call ‘Meslan,’ which is cooking an entire lamb on an iron pole skewer without chopping it,” al-Harshani says.

Hamama Arts

Salihi singing is famous among Hamamians. This bedouin style of singing is based on prolonging and mixing verses. Al-Harshani says that this style is rarely sung with musical instruments, such as the tambourine, drums, or gasba.

The use of tattoos is also a unique characteristic of the tribe. Tribal women get tattoos to display their affiliation with the tribe. They tattoo certain symbols on their face, hands, breasts and legs. Although men also get tattoos on their bodies, they do so to a lesser extent than women.

Hamamian Women

The Hamamian women have more freedom than women in other bedouin societies. In this regard, al-Harshani says: “Bedouin life dictates that women participate in most family matters, outside the borders of her tent or house. That’s why their clothes reflect more freedom. The Hamamian woman does not wear the safseri or a veil that covers her face; she only wears the ‘Aksah,’ which only covers part of her hair.”

This freedom is more evident through the lack of strict gender separation. Al-Harshani states that weddings and visits to the shrines of the Awliya are common and mixed activities in which women may dance and sing along with men.

Hamamian Men

The Bedouin passion and background rule the Hamamian culture, as tribal members help each other when in need. At the same time, they are known for blind anger and to only bear hardship for their families and close branches of their tribe.

For centuries, the Hamamian man was known to be highly emotional. Al-Harshani describes the Hamamian man, saying, “He gets excited and angry quickly but feels cold and lost just as fast. He loves independence and freedom to the point of chaos, is prideful to the point of vanity, and most importantly, so patriotic that he would thoughtlessly sacrifice his life.”