Introduction

The modern history of Kuwait begins in the early 17th century when the present territory of Kuwait was considered part of the tribal territory of the Bani Khalid, a powerful Bedouin tribal federation controlling north-eastern Arabia. Kuwait was still sparsely inhabited. There was a tiny fishing settlement on the southern shore of Kuwait Bay, called al-Qurain (Little Hill), in reference to the elevated patch of land that protected the cluster of tents and huts from tidal encroachment.

During the 1670s or 1680s, Sheikh Barrak bin Ghurair of the Bani Khalid build a small fort (Arabic kuwayt) at Al-Qurain. This fort, which gave Kuwait its present name, no longer exists. The original site of the fort is in the present al-Watiya neighbourhood of Kuwait City. During the late 17th and early 18th centuries, a succession of severe droughts struck the Najd region of central Arabia.

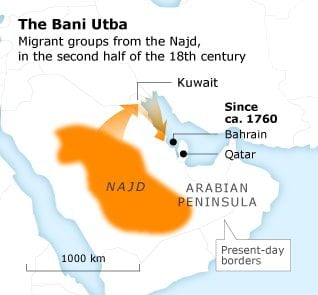

In response, Bedouin families from this region took what was left of their herds and migrated to the coastal regions of the Gulf, looking for additional means of subsistence in maritime activities such as pearling, fishing, sea trade, and piracy. In this transformation from a nomadic to a semi-settled, semi-maritime lifestyle, these enterprising migrants appear to have been very successful.

Their example was followed by other families and clans. Collectively, these migrant groups from the Najd became known as the Bani Utba. Among them were the nuclei of the later Al Sabah, Al Khalifa, and al-Jalahima clans, all of which would come to play a primary role in the history of the modern states of Kuwait, Bahrain, and Qatar.

It is unclear when the first Bani Utba settled in Kuwait. The present Sabah family claims to have arrived as early as 1613, but modern historians trace their arrival to the first half of the 18th century. According to local tradition, the Al-Sabah soon rose to prominence as the family to whom was allotted control of tax collection, military affairs, and external contacts.

The Bani Utba took advantage of the fact that the main regional powers – the Bani Khalid, and the Ottoman Turks that controlled Iraq – were both in decline by the latter half of the 18th century. This allowed the Bani Utba to gain control of Kuwait and strengthen its commercial network along the coasts of the Gulf and southern Asia.

Kuwait soon thrived as an entrepôt for interregional trade in horses, ghee, pearls, wood, spices, slaves, and other merchandise.

While the weakening of Bani Khalid power was in many ways beneficial to the Bani Utba, it also exposed them to external threats, because Bani Khalid warriors no longer provided a defensive shield. The military position of Kuwait’s Bani Utba was further weakened by the departure of most Al-Khalifa and al-Jalahima families for eastern Qatar, beginning in the 1760s.

Their migration may have been motivated by the growing power of the Al-Sabah clan. From their base in Qatar, the Al-Khalifa and al-Jalahima would soon wrest Bahrain from Persian overlordship. To this day, Al-Khalifa sheikhs continue to rule the Bahrain archipelago, while Al-Sabah sheikhs rule Kuwait. The less fortunate Jalahima failed to establish their own power base, although they would continue to harass their former fellow-travellers for some time.

Foreign Powers

Both the Al-Sabah and the Al-Khalifa have always been obliged to turn to powerful third parties to protect their interests. They cannot survive on their own: their numbers are insufficient to repel the major aggressors who arise at frequent intervals in this part of the world. In 1794, the Bani Saud of Najd and their Wahhabi allies could be prevented from taking Kuwait only by the military intervention of the British East India Company.

The Kuwaitis were no strangers to the British in India. Kuwaiti merchants regularly shipped thoroughbred Arabian horses for the British army in South Asia, among other merchandise. Earlier in the century, the East India Company had established a factory-fort in nearby Basra, which was of prime importance for imperial mail communications.

When Basra was struck by the plague in 1775 and invaded by the Persians, British mail was for some years routed through Kuwait with the consent of the leading Al Sabah sheikh, Abdullah I (1740-1814).

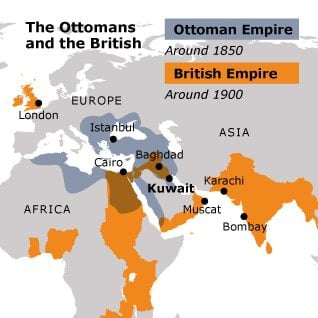

In the course of the 19th century British India – represented from 1858 on by the British Government of India – strengthened its position in the Gulf. The government of India was determined to keep its lines of communication with the London open and its geopolitical competitors at a safe distance. The strengthening of the British-Indian position in the Gulf, in turn, triggered an expansionist policy by the Ottoman governor of Baghdad, Midhat Pasha, who realized that Ottoman interests in the region were being seriously threatened.

By the second half of the 19th century, the British had signed ‘peace treaties’ with virtually every major tribal sheikh of the Gulf, except for Abdullah II (1814-1892) of Kuwait. So, when Midhat Pasha decided to recapture eastern Arabia in 1870, he could safely pressure Abdullah II to assist him militarily. In 1871, Abdullah accepted Ottoman suzerainty and received the title of kaymakam (district officer). Kuwait had formally become part of the province of Basra of the Ottoman Empire.

But the imperial power of the Ottomans was actually very weak. They would never be able to rule Kuwait directly. In 1896 a violent palace coup brought Mubarak al-Sabah (1837-1915) to power in Kuwait. Realizing the weak position of the Ottoman Empire in the face of European global hegemony, he strengthened Kuwaiti ties with Great Britain.

For their part, the British were keen to prevent the actual integration of Kuwait into the Ottoman Empire. In 1899, Mubarak signed a secret agreement with the government of India, in which he handed over control of Kuwait’s foreign relations to the latter.

In return, Mubarak received a yearly payment and a vague promise of protection from external aggression. A Kuwaiti merchant was appointed as a local political agent, to be replaced in 1904 by a British Government of India official.