Introduction

Kuwait has no obvious long-standing cultural tradition like its neighbour Iraq. Its small population descends from conservative Bedouin communities, and its relationship with modern culture has always been uneasy.

Kuwait’s oil wealth helped transform the country into an economic powerhouse. Kuwait’s boom began in the 1950s and 60s, before the economic expansion of most other states of the Gulf region – in fact, before some of those states had even come into existence. Right from the start, Kuwait intended to develop its culture as well as its economy. This was at the peak of urban Arab culture of Egypt and Lebanon, which established a benchmark for other Arab countries. This process was not only enthusiastically embraced by the Kuwaitis themselves but also, to a large extent, by immigrants from Egypt, Syria, Lebanon, and especially the Palestinian Territories.

Another obvious role model for Kuwait was its economically and culturally thriving neighbour Iraq, whose large cities were moving towards a regionally coloured modernity. Iraq’s example was much more attractive than that of Kuwait’s other neighbour, Saudi Arabia – that is, until Iraq turned against its small neighbour.

After Iraq invaded the country in 1990 Kuwait’s cultural life was almost obliterated, and the country has hardly recovered. This was due not only to the physical and economic damage and the effect of the Iraqi terror on the Kuwaitis themselves, but also to the fact that many immigrants had left the country. Most of the Palestinians were expelled from Kuwait, because Yasser Arafat’s PLO had maintained good relations with the regime of Saddam Hussein.

But other factors, too, slow Kuwait’s cultural development. Kuwait’s indigenous population is not more conservative than that of the Emirates or Qatar, but Kuwait developed a model of relatively moderate constitutional monarchy, and, through the parliamentary system, conservative parties have a greater say in the course of the country than in other Gulf nations.

Another difference is that the economic and ensuing cultural expansion of the Emirates and Qatar came later, coinciding with the globalization boom that took off in the 1990s. Dubai’s development became a media event. Kuwait could shy away from modernity as unnoticed as it had slipped in, outside the limelight.

The government has always played an important role in the development of Kuwait’s art world, notably through the National Council for Culture, Art, and Letters (NCCAL), which manages the nation’s cultural institutions, including museums.

Kuwait’s internationally orientated modern culture is now the exclusive domain of Kuwait’s globalized upper classes. Art collectors such as Sheikha Paula al-Sabah and her daughter Lula al-Sabah epitomize this underlying social rift in the nation.

Literature

Given its scarcely urbanized past, Kuwait has not produced what could be called classic literature, but, thanks to its high education level, Kuwait has produced several important contemporary writers.

Ismail Fahd Ismail (born 1940) was one of the first to establish a reputation in the Arab world and is the most prolific writer in the history of the country, with over twenty novels and numerous short-story collections.

Among the most notable Kuwait authors is Taleb al-Refai (b. 1958), journalist, writer, and a NCCAL employee. He produces the monthly arts magazine Jaridat al-Funun. His novels include Zill al-Shams (Shadow of the Sun, 1998), which was considered controversial. Raihat al-Bahr (The Scent of the Sea, 2002) nevertheless won the Kuwait National Award for Arts and Literature. Fatma Yousif al-Ali (b. 1953), after graduating in Arabic literature from Cairo University, became Kuwait’s first woman novelist. She is a prominent member of the Kuwaiti Literary Association.

Laila al-Othman (b. 1945) is a short-story author. Kuwaiti novelists and poets sometimes get into the news not for their literary merits but for running afoul of limitations on freedom of expression. In 2000, Human Rights Watch mentioned that a Kuwaiti court had sentenced Laila al-Othman and Kuwait University philosophy professor/poetess Aliya Shuayb to two months in prison for writings the court considered blasphemous and indecent, although both claimed they had consulted various Islamic legal academics confirming the opposite.

Music and Dance

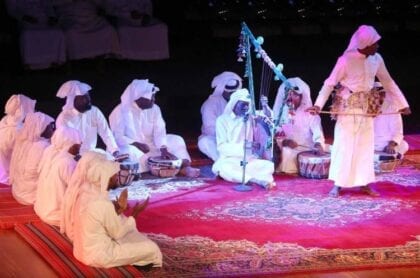

Kuwait shares with the wider Gulf region the musical traditions of Bedouins, from the land, and fishermen, from the sea, including the famed pearl-fishers’ chants. Kuwait also had some tradition of urban music when Kuwait City was a not unimportant port city lying between the Gulf and the hinterland.

Kuwaiti music and dance show connections with the music of southern Iraq and south-eastern Iran, which were once part of the same region, before borders were drawn. The music of the Gulf also has roots in African music, due to the extensive connections with East Africa, including the slave trade and immigration.

Nearby Oman was long part of a large empire that included Zanzibar and Baluchistan. Kuwait’s musical traditions were well recorded until the Iraqi occupation, during which the music archives were destroyed.

Because of its early cultural development, Kuwait, along with Bahrain, entered the 20th-century Arabic music world much earlier than the other Gulf States. With Bahrain, Kuwait is the centre of sawt, a popular musical style with its roots in several traditions, including, for instance, the African-sounding Khaliji (Gulf) rhythms.

Kuwait has produced – and still produces – major Arabic pop stars, many of them drawing inspiration from local traditions, mixing sawt with Europop influences. Nawal al-Kuwaitia (b. 1961), Nabeel Shoail (b. 1962), and Abdallah al-Rowaished (b. 1966) are the most popular modern performers. During the 1980s, they were all household names in Iraq, too.

In 2001 Abdallah al-Rowaished was censured in a fatwa issued by a Saudi cleric, who accused him of ‘insulting the Koran’ by putting its opening chapter to music.

That ruling was, however, overruled by a fatwa of the leading Kuwaiti cleric. This clip from 1978 by a popular Lebanese group of the time, the Bendaly family, shot in Kuwait, illustrates the cultural climate of Kuwait in the 1970s.

The song is trivial, but it is a unique mixture of an Arab sound, including Khaliji rhythms, combined with Western-pop-style close harmony, and even sometimes a funky bass-line – it was the height of funk and disco in Western music – English lyrics, and the, for some, quite un-Kuwaiti dancing by women.

The Miami Band became popular during the first decade of this century, starting out as a Kuwaiti boy band. Khaled Miami became the face of the ensemble, which was popularized when the group was embraced by Rotana TV.

Kuwait itself has no proper performance hall and no organization for Western classical-music concerts, although embassies sometimes organize events in collaboration with hotels. Kuwait, unlike other small Gulf States, has no important international cultural festivals.

Visual Arts

The visual arts have not gained the stature they have attained in Dubai, Abu Dhabi, or Doha. The state is much less a driving force than in Abu Dhabi or Doha, and Kuwait cannot compete with Dubai’s free-enterprise, independent-gallery culture. Kuwait is, to a remarkable extent, lagging behind the other richest Gulf States, but several principal members of the ruling family are famous art collectors, including Paula al-Sabah and her daughter Lulu al-Sabah.

Private galleries – including the Sultan Gallery of Farida Sultan, the Contemporary Art Platform of Amer Huneidi, and the Boushahri Gallery of Rana Sadik and Jawad Boushahri – are currently the most active in promoting new contemporary arts.

In the field of Islamic art, Sheikha Hussa and Sheikh Nasser, both also part of the Sabah family, own the renowned Dar al-Athar al-Islamiyya collection. As is the case with the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha, Kuwait has never itself produced Islamic art of any stature, so the collection comprises artefacts from the historical centres of the Islamic world.

Museums

The Iraqi invasion of Kuwait is reflected in a number of Kuwait’s museums. The Kuwait National Memorial Museum in Shuwaikh commemorates the Iraqi invasion and liberation of Kuwait. It exhibits a miniature version of Kuwait City telling the story of the invasion with visual and audio effects. Exposing ‘Saddam Hussein regime crimes’ both before and during the invasion, the propaganda is not to be missed. The al-Qurayn Martyrs’ Museum is another memorial of the invasion. It is a house in the residential suburb of al-Qurayn where members of a Kuwaiti resistance group were attacked by Iraqi troops on 24 February 1991. Following a heavy battle, the Kuwaiti men were defeated by the Iraqis and their house destroyed. The villa was restored as a museum, where visitors can see the damage inflicted on the house and the vehicles and belongings of the Kuwaiti men and Iraqi troops.

The Kuwait National Museum, which was severely damaged and looted during the Iraqi invasion, has two collections, archaeology and traditional Kuwaiti life. The museum is still under renovation. A large new wing is being built to house the famous Dar al-Athar al-Islamiyya collection of Islamic art, which has been temporarily housed at the Amricani Cultural Centre, in the former American Mission Hospital. Amricani Cultural Centre also has other exhibitions and organizes courses and cultural events.

The Al Hashemi Marine Museum exhibits a number of historic dhows of the Arabian Gulf, formerly used for the pearling industry and for transporting water. The adjacent Al Hashemi II, a giant copy of an Arabian dhow, forms a unique landmark on the coast of Kuwait. With a length of 80.4 metres, a width of 18.7 metres and an estimated weight of 2,500 tons, it was built as a private initiative in 1997 to preserve Kuwait’s maritime heritage for future generations.

The Tareq Rajab Museum houses an impressive private collection of artifacts from the Islamic world, from costumes and jewellery to manuscripts and ceramics. The nearby Tareq Rajab Calligraphy Museum, opened in 2007, exhibits a wide range of Arabic calligraphy.

The Dickson House Cultural Centre on the coast is one the few remaining old houses in Kuwait. Originally built for a Kuwaiti merchant in 1870, it served as the residence for British political agents in Kuwait after the British signed an agreement with Mubarak al-Kabir in 1899. The last British commissioner Harold Dickson lived in the house until 1959. The Dickson House exhibits pictures of the family living in the house and documents of the agreement that the British government signed with the Kuwaiti Emir. It was renovated by the National Council for Culture, Arts and Literature and is now a museum.

Other cultural spots in Kuwait are Beit Lothan, for Kuwaiti contemporary artists and youth creativity activities, the Science and National History Museum, and The Museum of Modern Art, which contains paintings from the Kuwaiti modernist period of the second half of the 20th century. The Youm al-Bahhar Village on the coast is a reconstructed ancient village exhibiting arts and crafts.

Architecture

Compared to the Emirates and Qatar, Kuwait’s modern architecture is restrained. The most notable cultural landmarks are the Kuwait Towers, dating from the 1970s, designed by the Swedish architects Sune Lindström and Malene Björn. The National Assembly Building, resembling Bedouin tents, is a landmark too, designed by Jørn Utzen, who also did the Sydney Opera House. Opened in 1985, it is distinctive in an another sense as well, being the first parliament building in the Gulf States. The Babtain Public Library is another recently constructed landmark.

Construction work in Kuwait City witnessed the emergence of a number of modern skyscrapers the most recent addition being the 412-meter-high Al Hamra Tower, which was inaugurated in 2012. The impressive tower, now Kuwait’s tallest, is sculpted to minimize solar radiation. Another recent construction, but of a very different kind, is the Sadeeqa Fatima al-Zahra Mosque, opened in 2011. This new Shia mosque in the Abdallah al-Mubarak area, is a copy of the famous Taj Mahal mausoleum in India. Although much smaller than the original, it is a new iconic landmark on the outskirts of Kuwait City.

Despite modern construction, a few examples of architecture from the pre-oil era of Kuwait have survived. Most old houses are along the Arabian Gulf Street in Kuwait City. Beit Dickson was built in 1870 for a Kuwaiti merchant. It has served as the residence of British political agents in Kuwait. The house is an example of a mixture of local and colonial architecture.

Beit al-Sadu, built in 1929, is a mixture of local and Indian architecture. According to the website ArchOfKuwait, Beit Sadu is Kuwait’s earliest house built of cement and concrete. Since 1979, it houses an exhibition on the art of Bedouin weaving.

In 2010, the historic Sheikh Mubarak stall near the Souq Mubarakiya in Kuwait City was renovated. In the early 20th century the Kiosk served as Mubarak al-Sabah’s (al-Kabir) office, where he collected toll, controlled trade through camel caravans and consulted with the people. Sheikh Mubarak built two kiosks in the area, of which the southern was used in the morning and the northern in the afternoon.

Another historical building is the al-Qibliya School for Girls, in the Qibla area in Kuwait City. Originally built as a house in 1942-1943, it was converted into a girls’ school. Constructed from sea brick, mud, bamboo and wood imported from India and East Africa, it collapsed in 1945 due to significant rainfall. The National Council for Culture, Arts and Literature renovated the building and reopened it in 2001.

Traditional Architecture

Modern Architecture

Theatre

From the 1950s to the 1990s Kuwait had a theatre life similar to that of Egypt, Syria, and Iraq, sponsored by a supportive government. The city boasted several well-equipped modern theatre buildings. But here too the Iraqi invasion and subsequent political changes took their toll. Theatre life is now struggling, except for comedy theatre, and some of the buildings are in disrepair.

The most internationally prominent Kuwaiti theatre director and playwright is Sulayman al-Bassam (1972), although he is based mostly in London, where he founded the Zaoum theatre company, with a homeland branch, the Sulayman al-Bassam Theatre Kuwait. Famous productions that have toured internationally include The Al-Hamlet Summit and Richard III, an Arab Tragedy, which transpose Shakespeare’s plots dealing with intrigues (including murder) between factions inside medieval ruling families, into what resembles a present-day court in some Gulf State.

Some found the effect superficial, catering, in fact, to prejudices among a Western audience. While the producers claim they want to break through stereotypes, the plays instead confirmed them. These productions are seldom staged in any Gulf State.

Film

Two well-known feature films have been produced in Kuwait, Bas ya bahr (Cruel Sea, 1972) and Urs al-Zayn (The Wedding of Zein, 1976), both directed by Khalid al-Siddiq. The Cruel Sea was the first feature film to be made in a Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) country. Kuwait became the only GCC nation so far to submit a movie for the Academy Awards (Oscars).

The film also played at the subsequent Venice Film Festival. It is about the son of a poor pearl diver who loves a merchant’s daughter betrothed to an elderly man. While diving the youth gets his hand trapped by a huge clam. His friend has to amputate his hand in order to rescue him, but the young man drowns before being brought to the boat.

His beloved, meanwhile, is raped by her husband on her wedding night. The friend looks through the dead boy’s cache of oysters and finds a huge pearl. He hopes that, by giving it to his friend’s family, his friend’s death might not be in vain. When the boy’s mother is confronted with her son’s body and the pearl, she scorns the sea and flings the pearl back.

The Wedding of Zein is based on a novel written in 1969 by the influential Sudanese author Tayeb Salih. It portrays the life of villagers in northern Sudan and deals with social restrictions, economic boundaries, and people trying to break through, this time with a happy ending.

Another famous movie is closely associated with Kuwait. The 1972 Syrian film al-Makhdu’un (The Duped), shot in Syria by Egyptian director Tawfik Saleh, based on Palestinian author Ghassan Kanafani’s story Rijal fi al-Shams (Men in the Sun), portrays three Palestinian refugees of different generations trying to find their way from Iraq to Kuwait, the land of promise. But they die on Kuwait’s border, suffocated in the road tanker they were hiding in.

Several Western films have been shot in Kuwait, including The 13th Warrior (1999) by John McTiernan, starring Antonio Banderas.

Kahin Na Kahin Milenge is a Bollywood movie produced in Kuwait in 2009. While the West is often said to stereotype Arabs in movies, here Kuwait helped Bollywood do so. The film suggests that Arabs do little but dance and sing in the streets.

The movie is about an Indian who came to Kuwait more than 25 years ago to make a living and save money so that he could retire to his hometown. Finally the day comes when he plans to return, but his daughter now considers Kuwait her motherland and prefers to stay.

Sports

Kuwait holds no major sports events. No tennis stars play there, there is no sponsorship of major football clubs, no Formula 1 racing championships, and no internationally significant horse races.

Kuwait has, however, participated in twelve Olympic Games and three times has taken home bronze medals, in 1992 in Barcelona in taekwondo and in 2000 in Sydney and 2012 in London in double trap-shooting, won both times by Fehaid al-Deehani.

Kuwait’s national football team has also had some success. Nicknamed ‘The Blue’, they made it to the World Cup finals in 1982, managing a draw with Czechoslovakia but losing to England and France. They were even more successful in the competition for the Asian Cup, reaching the finals in 1976 and taking home the winner’s trophy in 1980.

Kuwait’s 20–0 win over Bhutan in 2000 was, at the time, the most lopsided win ever in international football. In the same year, Kuwait’s football team took part in the Sydney Olympic Games. In 2007 Kuwait was suspended by FIFA from all participation in international football, on the grounds of governmental interference in the national football association.

In basketball, another popular sport, the national team has participated eleven times in the FIBA Asian Championship but has brought home no medals. Cricket, handball, and rugby are also popular.

Further Reading

Below are the publications by acclaimed journalists and academics concerning the culture of Kuwait section of this country file:

Latest Articles

Below are the latest articles by acclaimed journalists and academics concerning the topic ‘Culture’ and ‘Kuwait’. These articles are posted in this country file or elsewhere on our website: