‘Build the wall’ was one of Donald’s Trump’s key election promises and a slogan that is now known the world over. Yet while this has focused global attention on the US-Mexico border, in recent years border barriers have by no means solely been an American obsession.

Since the Berlin Wall and Iron Curtain fell in 1989, the ‘separation barrier’ built by Israel along its disputed border with the West Bank has held the unenviable position of being the world’s most infamous wall, and even served as inspiration for Trump.

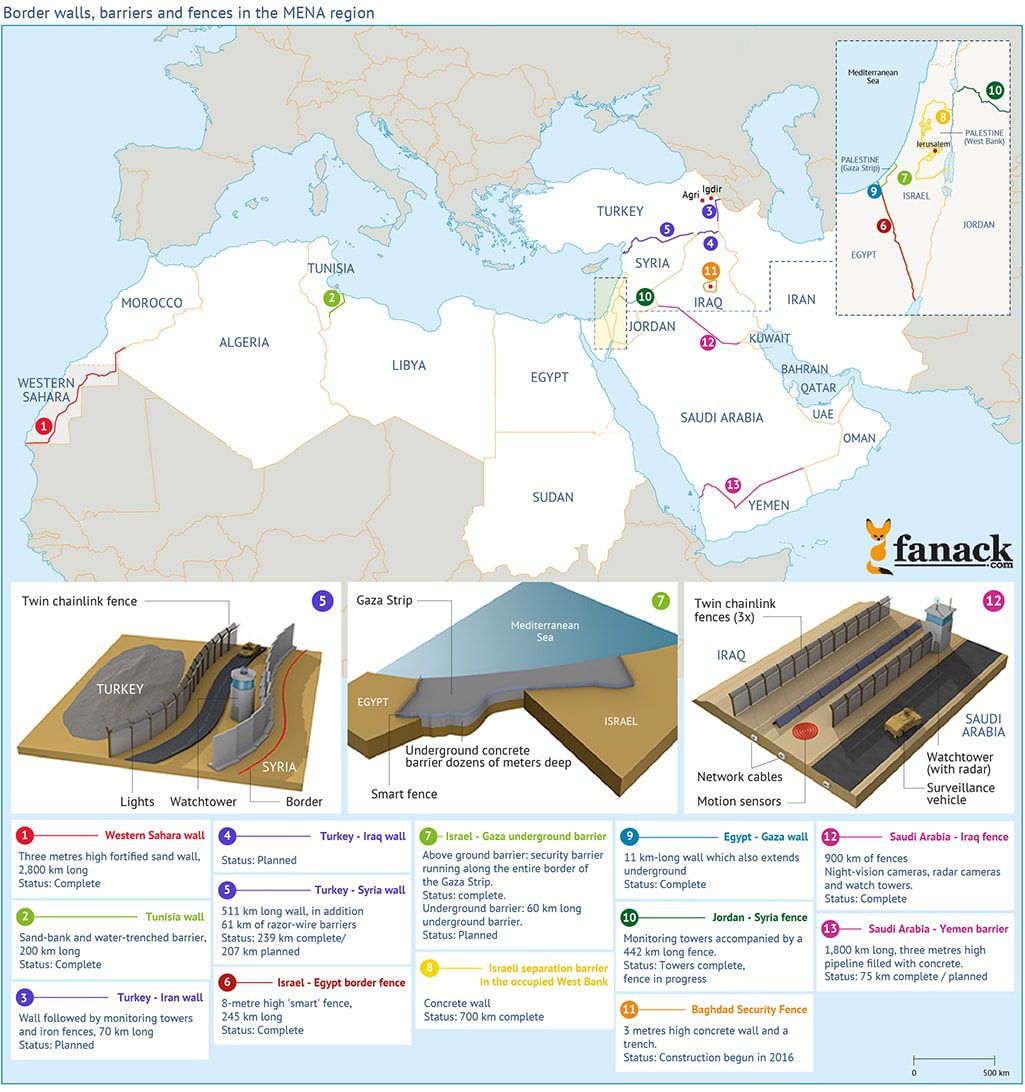

Trump invoked Israel’s ‘wall’ as a model for the concrete frontier he hoped to erect along the border with Mexico. Construction of Israel’s separation barrier began in 2002 during the second intifada, when Palestinian suicide bombers were targeting Israeli towns. It was billed as a security measure and Ariel Sharon, then prime minister, was keen for it not to be seen as signifying Israel’s border; his vision of Israel’s rightful territory was far more expansive.

Tunnels have since punched holes in the confidence Israel once had in border walls. In the 2014 war between Israel and Hamas in the Gaza Strip, the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) destroyed some 32 tunnels used by Palestinian militants to penetrate Israeli defences. Following the end of fighting, Israel began work on a 60 km underground barrier, taking the border wall into subterranean realms. This new barrier supplements the wall that has isolated Gaza since the settler evacuation in 2005.

However, Israel is not the first country to have used such measures. In 2010, Egypt completed its own 11km-long wall with Gaza that extended metres below the ground in an effort to thwart Gazan smuggling tunnels. Yet in 2016, the Egyptians were still discovering more tunnels; their wall only appears to have forced smugglers deeper underground.

Protecting against the ‘other’ is a theme common to all Middle Eastern border walls, but most have a firmer commitment to territorial demarcation. In May 2017, a Turkish newspaper reported that Ankara is planning a border wall along part, or all, of its border with Iran to restrict the movement of Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) militants. President Erdoğan has also promised a similar barrier along the Iraqi border, which PKK militants have long used to infiltrate Turkey. Along the Iranian border, a 70 km stretch near Ağrı and Iğdır will be walled off, and the rest will be monitored with towers and iron fences.

Turkey has long accused Iran of harbouring PKK affiliates and of turning a blind eye to PKK activities. The Iranian border town of Maku is known by locals as a hub of PKK activity. However, doubts have been raised as to whether it would even be possible to build a barrier along the Turkish-Iranian border given the high altitude and largely inaccessible terrain. Although an anti-PKK border wall is a convenient rhetorical tool for the Turkish government, the mountainous eastern border stands in stark contrast to the flat plain over which Turkey’s other border wall runs. In any event, Iran has welcomed the move. Tehran hopes a wall will alleviate the smuggling of alcohol and other goods, an illicit trade Tehran says is worth $2 billion annually.

One of the greatest drivers of wall-building in recent years has been the war in Syria. As the conflict has become more complex and the number of armed groups larger, Syria’s neighbours have increasingly seen border walls as a way to insulate themselves from the spillover.

In early 2017, Turkey announced the completion of half of a planned 511 km wall along its approximately 900 km border with Syria. Made from concrete blocks topped with razor wire, the wall is ostensibly to halt the cross-border movement of PKK militants and Islamic State (ISIS) fighters and can be removed if and when the security situation improves.

However, human rights groups have voiced concern that Syrian civilians fleeing the war will be stuck on the Syrian side of the border. According to Human Rights Watch, Turkish border guards have been involved in beating and firing at civilians trying to cross the border. Ironically, despite the wall’s purported raison d’etre, the Turkish government has in the past been accused of colluding with jihadist fighters in Syria.

In 2015, Saudi Arabia revealed it was building a nearly 1,000km wall and ditch along its border with Iraq to prevent the infiltration of armed fighters and insulate itself from the turmoil engulfing its neighbours. The border zone includes five layers of fencing with night-vision cameras, radar cameras and watchtowers, some of which IS has attacked.

Although plans for the wall began in 2006, IS’ annexation of much of Iraq gave added impetus to the project. In a similar effort, Saudi Arabia is also building a 1,800km wall along the southern border with Yemen, construction of which started in 2003.

In Iraq, the most obvious walls have American fingerprints on them. After the 2003 US invasion, concrete barriers sprung up in the capital Baghdad, isolating the American-populated Green zone. In subsequent years, these walls spread across the city, deliberately enhancing physical ethnic divisions in an effort to end the growing civil war.

In contrast, fear of IS has driven this most recent wave of frontier-building. In early 2016, Iraq began work on a trench and defence network along a 100km stretch of approaches to Baghdad, as the threat of IS entering the city still loomed large. Many also hoped that moving defences outside the city would limit the suffocating congestion caused by security checkpoints within Baghdad.

Lebanon has also turned to physical barriers to halt IS. The country is home to 12 fortifications built with British help along its north-eastern border with Syria, an area that was overrun by IS-linked militants in 2014. These defences have allowed Lebanese security forces to police the border effectively almost for the first time in the country’s history.

This wall-building enthusiasm has not been limited to Lebanon’s border. In 2016, the government began constructing an imposing concrete wall around the Ain al-Hilweh refugee camp, which is home to 70,000 Palestinian refugees and has long been a site of armed clashes between various militant groups. However, unlike most of the barriers mentioned here, this wall was in the middle of the country and highly visible, reinforcing Palestinian accusations of racism by the Lebanese government. After a public outcry, building of the wall, which resembled the separation barrier between Israel and the West Bank, was halted in November 2016.

Flush with Syrian refugees and with a long and porous desert border with Syria, Jordan has also given greater attention to border protection since 2011. However, its own wall-building programme began in 2008, as part of efforts to stop the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction. The $20 million project to erect a series of surveillance towers along a 50km stretch of the border has since expanded into a programme to detect IS fighters and arms smuggling costing half a billion dollars, with American taxpayers footing the bill.

Similarly concerned about deterring militants, in February 2016 Tunis announced the completion of the first part of a 200km barrier made of sand banks and water trenches along its border with Libya. The barrier was announced the previous summer after 38 people were killed at a beach resort by a gunman believed to have trained in Libya.

However, the region’s oldest and longest border wall is almost certainly its least well known. Completed in 1987, the ‘berm’ (as it is known locally) is a 2,800km-long, 3m-high fortified sand wall that bisects the disputed territory of Western Sahara, which Morocco annexed in 1979.

Since 1981, barbed wire, electric fences, thousands of troops and an estimated 7 million landmines have been put in place to keep out guerilla fighters and refugees from the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic.

Although hostilities officially ended in 1991, the wall is still heavily guarded with radar and other surveillance equipment. Despite this, fighters operating out of Algeria have occasionally been able to burrow under the wall, raising questions about whether a border can ever really be impenetrable.