Introduction

The Republic of Lebanon was established by the enacted Lebanese Constitution of 1926 and won its independence from France on 22 November 1943. Lebanon is a parliamentary democracy. Its capital is Beirut.

Lebanon was a founding member of both the United Nations and the League of Arab States. The Lebanese political system is formally based on the principles of separation, balance, and co-operation amongst the powers.

For all important political and administrative functions quota have been established along the lines of the percentage of the population belonging to the different religious communities.

The Presidency

The president of Lebanon is the head of state and the symbol of its unity. The parliament elects the president for a single term of six years. The president is not eligible for re-election until at least six years have passed from the end of the first term.

According to the 1926 constitution, which was adapted after the Taif Agreement brought an end to the civil war in 1989, the president must be a Maronite Christian. This confessional system is based on 1932 census data that showed the Maronite Christians as making up a substantial majority of the population and is meant to balance power among the country’s multiple sects.

The president is charged with observing the constitution and preserving Lebanon’s independence and territorial integrity, while simultaneously acting as the commander-in-chief of the Lebanese Armed Forces. On basis of parliamentary consultations, the president nominate the prime minister after consultation with the speaker of the parliament. The current president is Michel Aoun, who was elected on 31 October 2016.

The Executive

Executive power is entrusted to the Council of Ministers, which drafts general policy and oversees its execution in accordance with the effective laws.

The president appoints the head of the Council, i.e. the prime minister, in consultation with the parliament. The constitution states that the prime minister must be a Sunni Muslim.

The Council of Ministers is formed in agreement with the president following the parliamentary consultations. The president and the Council of Ministers need the support of a majority in parliament to hold their positions.

Following growing political tensions, Prime Minister Najib Mikati resigned on 23 March 2013. Tammam Salam was appointed as his successor. Saad Hariri has been prime minister since December 2016.

The Legislative

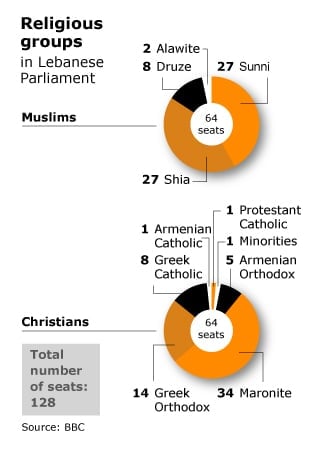

Legislative power is in the hands of the Assembly of Representatives (the parliament). The 128 parliamentary seats are confessionally distributed but members are elected by universal suffrage for a four-year term. Each religious community has an allotted number of seats. In addition, all candidates in a particular constituency, regardless of religion, must receive a plurality of the total vote.

The parliament elects one of its members as speaker for the same term but this, unlike the presidency, can be renewed. The constitution states that the speaker must be a Shia Muslim.

The Judicial

Judicial power rests with judicial courts of various degrees and levels of jurisdiction. Magistrates are formally independent in the exercise of their functions. Their decisions and judgments are rendered and executed in the name of the Lebanese people.

Lebanon has no civil code for personal status matters. The religious communities each have their own laws and tribunals for such matters as marriage, dowry, annulment of marriage, divorce, adoption, or inheritance. These laws are binding, whether one is a practising member of the community or not. Without registering with a religious community, people have no legal existence.

In the spring of 2010, a movement for secularism was created. By means of an impressive march, Laique Pride, it tried to put pressure on the Lebanese government to change this aspect of Lebanese laws.

A study, published in March 2010, on the democracy index in the Arab World, showed that although Lebanon ranks highest regarding respect for rights and freedoms and second highest in the sub-index relative to practices, it scored badly on violations of the Constitution, ill-treatment of detainees, arbitrary detention, personal safety, government expenditure on the social sectors, military courts, and school drop-outs. (See The State of Reform in the Arab World, 2009–2010. The Arab Democracy Index)

Local Government

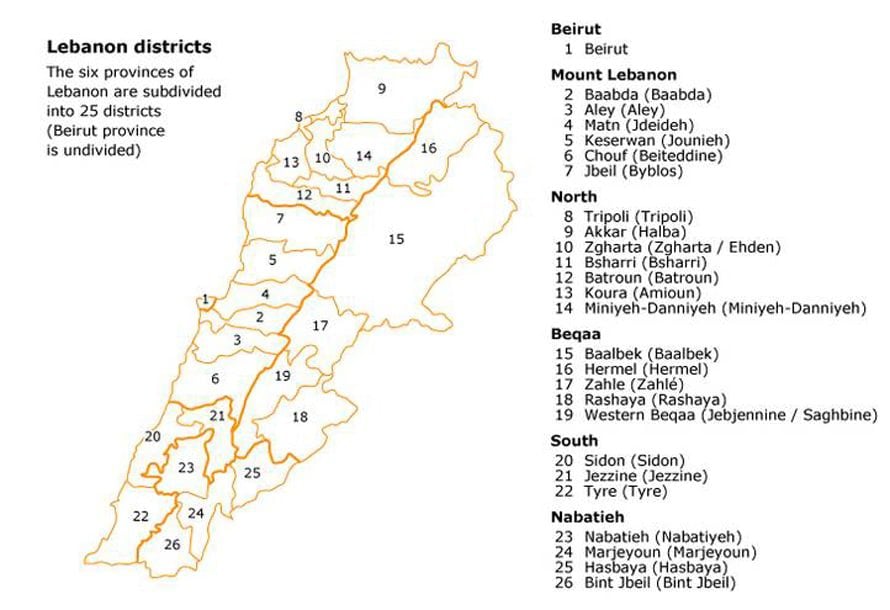

Lebanon is divided into six muhafazat (both provinces and electoral districts), and subdivided in 25 qadas or districts. The muhafazat are: Beirut (administrative centre: Beirut), North Lebanon (Tripoli or Tarabulus), Mount Lebanon (Baabda), Beqaa (Zahle), South Lebanon (Sidon or Saida), and Nabatieh (Nabatieh). Local communities or municipalities can vary from villages with 300 inhabitants to cities of half a million inhabitants.

According to the Constitution, local elections are held once every six years. However, they were suspended after 1963 and only resumed in 1998. In that year the country had to re-experience what local democracy meant.

In June 2004, new local governments, with limited powers and financial means, were elected for six years in the 944 municipalities that have at least 300 inhabitants. New municipal elections took place on four Sundays in May 2010.

Political Parties

From the 1960s the privileged position of the Maronite Christian community in Lebanon’s political system, which was based on the unwritten 1943 National Pact (Mithaq al-Watani) between the leaders of the Maronite and Sunni establishment, met with growing opposition from underrepresented parts of the population, mainly Shiites – then already the largest religious community – but also Sunnis and Christians. Their demand for more equal political representation and economic participation was resisted by the Maronite leadership.

The prominent Druze politician Kamal Jumblatt recognized the new reality. He became the leader of a coalition of discontented political forces – the Lebanese National Movement (LNM) – consisting of his own Progressive Socialist Party (PSP), the Lebanese Communist Party (LCP), the Organization of Communist Action (OCAL), the Syrian Social Nationalist Party (SSNP), two branches of the Arab Socialist Baath Party, the Independent Nasserite Movement (INM) and other Nasserist groups.

Several Palestinian political factions worked closely together with the LNM, including the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) and the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine (DFLP). The LNM demanded administrative reforms and the abolition of the confessional basis of Lebanese politics. It advocated freedom of action for Palestinian guerrilla fighters operating from the south of Lebanon against Israel.

The Civil War

After a bloody attack on 13 April 1975 in the streets of Beirut by Maronite fighters on Palestinian civilians – in hindsight the start of the Lebanese Civil War – Palestinian and LNM fighters clashed with Maronite militias: the Phalange of the Lebanese Phalanges Party (also known by its Arab name Kata’eb), the Marada Brigade of the Marada Movement and the Tigers of the National Liberal Party.

In January 1976, in reaction to the formation of the LNM, they formally joined forces and established the Lebanese Front with several small like-minded groups.

In this period Lebanese politics were dominated by important families such as the Chamoun, the Franjiyeh, the Gemayel, the Jumblatt, the Arslan and the al-Husaini. New families would rise to power later, of whom the Hariri is the most notable example.

In May 1976, at the request of the Maronite President Suleiman Franjiyeh, neighbouring Syria intervened militarily by sending a large force to Lebanon. This came after LNM fighters gained the upper hand in their confrontation with fighters of the Lebanese Front.

Preventing a LNM victory served Syrian interests, since a LNM-led Lebanon would increase the risk of a confrontation with Israel, possibly followed by the occupation of parts of the country, which would seriously undermine Syria’s geostrategic position vis-à-vis Israel.

After a series of military setbacks for the LNM the Lebanese Front and its armed wing, the Lebanese Forces led by Phalange commander Bashir Gemayel, no longer needed Syria’s support and wanted its troops to leave. The Front also opposed the activities of armed Palestinian groups.

Since Syria had no intention in leaving, the Front strengthened its ties with Israel; thus in return for intelligence on Palestinian and other groups Israel provided training and supplies. The 1978 Israeli invasion of South Lebanon, aimed to deal a heavy blow to the Palestinian resistance, received the Lebanese Front’s full support.

Closer ties with Israel, as well as his leadership aspirations would bring Bashir Gemayel in conflict with an important member of the Front, former Lebanese President and leader of the Marada Movement, Suleiman Franjiyeh. In June 1978 this resulted in a bloody confrontation, when the Phalange defeated the Marada Brigade. In a nightly raid a Phalange unit slaughtered Suleiman’s son Antoine (Tony) in his home, together with his immediate family.

In the wake of the Israeli invasion of Lebanon in the summer of 1982, aimed at crushing the organized military and political presence of the Palestinians in Lebanon and creating the conditions to install a pro-Israeli government, Bashir Gemayel was designated by Parliament to be Lebanon’s next President. However, before he was sworn in, he was killed in a heavy bomb attack for which the SSNP turned out to be responsible.

Thereupon Bashir’s brother and Phalange Party prominent, Amin Gemayel, was elected president. On 17 May 1983 his government took the highly controversial step of signing a peace treaty with Israel. This brought the government in an open conflict with its Lebanese opponents, supported by Syria, which still retained thousands of soldiers on Lebanese soil.

Amal and Hezbollah

Among them were parties which represented the Shiite community. In order to safeguard their interests and to realize their political objectives, many Shiites in the early stage of the Civil War had rallied behind what became the Amal (Hope) Movement, led by Nabih Berri.

After 1982, partly out of dissatisfaction with the passive policy of the Amal Movement with regard to the on-going Israeli occupation of parts of Lebanon, a number of Amal members left the movement and, with the active support of Iran, founded the Shiite Islamist-inspired Hezbollah (Party of God). Over the years the Party succeeded in building an extensive network to provide social services and education to the unprivileged, as well as an impressive military apparatus in order to resist the on-going occupation of South Lebanon by Israel.

In 1984 the Amal Movement, Hezbollah and the PSP (since 1976 led by Walid Jumblatt, after the murder of his father) confronted the Gemayel government with military action. Given that the Israeli forces had largely withdrawn, as had the American and French intervention force (after a series of suicide bomb attacks on their barracks), President Gemayel’s government quickly became isolated. Switching allegiances it turned to Syria (on 5 March 1984 the peace treaty with Israel was abrogated).

On 28 December 1985, under Syrian auspices, the Amal Movement, the PSP and the Lebanese Forces (now led by Elie Hobeika) signed a Tripartite Accord in Damascus in an effort to end the Civil War. The agreement turned out to be highly controversial among the Lebanese Forces, and led to the downfall of Hobeika (in 2002 he died a violent death in Beirut after his car was blown up by unknown perpetrators).

In turn President Gemayel and the (Maronite) Chief of Staff of the Lebanese Armed Forces, General Michel Aoun, rejected the clauses in the agreement concerning a further role of Syria in Lebanese politics. In January 1986, after Samir Geagea assumed the leadership of the Lebanese Forces, the Tripartite Agreement collapsed.

Desintegration and the Taif Agreement

In all, by the mid-1980s, the various militias had established influential positions, each controlling a part of the country: the Lebanese Forces Beirut and the region north of Beirut, the PSP the Druze homeland of the Shuf, the Amal Movement and Hezbollah Beirut’s southern suburbs, southern Lebanon and the Beqaa Valley. Lebanon as a state threatened to fall apart.

This became painfully clear in September 1988 after President Gemayel’s mandate expired and the various communities could not agree on his successor’s election. Chief of Staff General Aoun subsequently stepped in as caretaker Prime Minister. On 14 March 1989, after a Syrian attack on the Baabda presidential palace and on the Ministry of Defence, Aoun declared a War of Liberation on the Syrian army. Although he could count on support from Christians as well as some Muslims, the killing of thousands of civilians and large-scale destruction as a result of artillery exchanges with the Syrian army eventually turned against him.

Alarmed by the threat of a further escalation of the conflict, the Arab League in 1989 intervened and brought Lebanese parliamentarians together in Taif (Saudi Arabia) to negotiate a fairer redistribution of power between the various communities – all within the parameters of the existing confessional political system – and to elect a new President. This resulted in the so-called National Reconciliation Accord, better known as the Taif Agreement. The Accord was rejected by caretaker Prime Minister Aoun because of the role of ‘guardian’ bestowed upon Syria in the Agreement.

The Taif Agreement resulted in a greater political representation for the Muslim population, which had become a numerical majority. The Agreement provided for an equal allocation of seats in Parliament for Muslims and Christians (the number of seats was increased from 99 to 128). In addition, seats were to be divided proportionately between the various denominations and proportionately between the districts.

The (Maronite) President ceded powers to the (Sunni) Prime Minister and to the Council of Ministers, while the position of the (Shiite) Speaker gained importance as his term of office was extended to four years. Positions in the civil service would rely on ‘capability and specialization’ instead of the ‘sectarian representation base’ (which meant that jobs would not be allocated to members of a specific denomination).

On 13 October 1990 Aoun was finally defeated by Syrian air and ground forces. This day marks the official end to the Civil War, which had dragged on for a period of fifteen years. Aoun was given a free passage to France, where he would spend the following fifteen years living in exile.

The various militias were disarmed after 1990 as part of the Taif Agreement – except for Hezbollah, as it continued to resist the on-going occupation of South Lebanon by Israel. Trained and financed by Iran, Hezbollah could fall back on an elite professional force of 2,000-3,000 men and was better armed and trained than the Lebanese army. Building up military pressure, Hezbollah, in 2000, forced Israel to unilaterally withdraw from South Lebanon.

1992 General elections

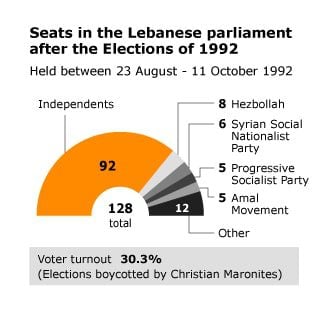

General elections were held in 1992 (the first since 1972). Most Maronites boycotted them as they considered themselves to have lost out in the Taif Agreement. This explains why the voter turnout was a mere 30.3 percent, the lowest since independence in 1943. Independent candidates won the majority of seats, 68 of whom were members of various blocs.

The elections led to the creation of a government presided over by Sunni Prime Minister (and billionaire) Rafiq Hariri. His government spearheaded the reconstruction of Lebanon. Hezbollah, now led by secretary-general Hassan Nasrallah, participated in the elections and entered Parliament.

After a two-year absence Hariri was reappointed as Prime Minister. After his resignation in 2004, due to growing disagreement with the pro-Syrian President Emile Lahoud, whose term in office was extended under Syrian pressure, Hariri established an opposition coalition together with the Christian Qurnat Shehwan Gathering and the Free Patriotic Movement (led by Michel Aoun), as well as Jumblatt’s PSP. Hariri’s coalition aimed at overturning the Syrian-backed successor government, to ‘recover Lebanese independence’.

After the assassination of Rafiq Hariri on 14 February 2005 by a car bomb in Beirut, purportedly orchestrated by Syria, hundreds of thousands of Lebanese took to the streets in protest, demanding the immediate withdrawal of all Syrian troops from Lebanese soil. Under mounting interior and international pressure Syria was left no other option than to withdraw its troops, which was completed by the end of March 2005.

Two Camps

Anti- and pro-Syrian mass demonstrations have led to the creation of two ideologically opposed political blocs in Lebanese politics.

March 14 Alliance

The March 14 Alliance, named after the anti-Syrian demonstration in Beirut on 14 March 2005 (viewed as the start of the so-called Cedar Revolution), was formed around the late Hariri’s Sunni-dominated Future Movement. United in their desire to see the end of the Syrian occupation in Lebanon, political leaders from the Sunni, Maronite and Druze communities joined forces. Led by Rafiq Hariri’s son Saad, March 14 included Jumblatt’s Progressive Socialist Party (PSP) and a number of Maronite political figures including Aoun’s (returned from exile) Free Patriotic Movement and Samir Geagea’s Lebanese Forces. Its programme aimed at:

1. Freeing Lebanon from Syrian control;

2. Normalization of relations between Lebanon and Syria;

3. Re-establishment of Lebanese state control over the whole of Lebanon, including disarming Hezbollah and other armed (mainly Palestinian) groups;

4. Establishing the Hariri Tribunal to investigate the assassination of Rafiq Hariri;

5. Working with the international community to establish the basis for a strong economy.

Although victorious in the elections of 2005 and 2009, the alliance lacked effectiveness and suffered from internal problems. Having joined forces in their common goal to free Lebanon from Syrian control, the various political groups lacked further common ground. The withdrawal in 2005 of Aoun’s Free Patriotic Movement from the March 14 Alliance and his joining of the March 8 Alliance, dealt a large blow.

Aoun took this step after it became clear that other March 14 Alliance leaders would not give him their support on becoming Lebanon’s next President. As a result the March 14 Alliance lost the support of the majority of the Christians. Since then the Alliance has been dominated by Hariri’s Sunni-dominated Future Movement.

March 8 Alliance

The pro-Syrian March 8 Alliance opposed the aims of the March 14 Alliance. Named after the date of its massive pro-Syrian demonstration, the March 8 Alliance was led by Hezbollah and the Amal Movement, which remained Syria’s allies. Its programme was aimed at:

1. Maintaining close ties with Syria and Iran;

2. Ensuring that Hezbollah be allowed to maintain its arms to continue its resistance against Israel;

3. Ensuring that the Lebanese government would adopt this language of resistance.

Hezbollah came to dominate the March 8 Alliance as a result of its organizational strength and military capabilities. In the 2005 general elections the March 8 Alliance won 57 of the 128 seats in Parliament, consequently laying claim to roughly a third of the cabinet seats in the government led by Fouad Siniora of the Future Movement.

In addition Hezbollah obtained several key positions in state institutions, such as the Military Tribunal, in general security and in airport security – all crucial with respect to its on-going low intensity war with Israel.

Further Division

The March 14 Alliance blamed Hezbollah for provoking the July 2006 Israeli offensive, which resulted in a large number of casualties and in large-scale material destruction, mainly in the Beirut area and in the south of the country.

In November of that year things got worse after a draft UN protocol for the Special Tribunal for Lebanon, set up to find out who was behind the assassination of Rafiq Hariri, was submitted to the Lebanese government and Parliament for approval.

Hezbollah denounced the Tribunal as an Israeli-American plot against Syria and itself (in a later stage arrest warrants were issued against several of Hezbollah-affiliated suspects), demanding that the Lebanese government renounce it. However, the March 14 Alliance refused to do so, and as a result all March 8 Alliance ministers resigned from government.

In May 2008 efforts by the Future Movement-led government to curtail Hezbollah’s freedom of action led to escalating tensions. Hezbollah and its allies dealt a significant military blow to fighters of the March 14 Alliance, briefly taking over Sunni West-Beirut – March 14’s main political basis. Crucially for Hezbollah, Aoun’s Free Patriotic Movement sanctioned the move, referring to the organization’s right to self-defence. The conflict ended after a negotiated settlement was reached in Doha (Qatar) on 16 May 2008.

Five months after the June 2009 general elections a ‘government of national union’ was formed, led by Prime Minister Saad Hariri, in which ministers of both Hezbollah and the Amal Movement participated. However, in January 2011, the government collapsed after all the March 8 Alliance ministers resigned over Prime Minster Hariri’s refusal to call an emergency cabinet session on withdrawing cooperation from the Special Tribunal for Lebanon. A new, Hezbollah-dominated government was formed in June of that year (without the Future Movement), led by Prime Minister Najib Mikati.

Since the outbreak of the popular uprising in neighbouring Syria in the spring of 2011 – and its brutal repression by the regime of Bashar al-Assad ever since – the political tensions between Hezbollah and in particular the Future Movement and Sunni salafist groups have sharply increased. Hezbollah has sided with the Syrian regime – with Iran acting as an important ally in the on-going confrontation with the United States and Israel. In April 2013 Hezbollah leader Sayyed Hassan Nasrallah publicly admitted that his forces have been involved in a military offensive against the Syrian opposition fighters.

Involvement of Shiite and Sunni forces in the conflict in Syria, has left Lebanon in a precarious position. Prime Minister Mikati had to vacillate between Sunni support for the Syrian uprising and the official dissociation policy towards Syria. In order not to lose its strong (military) position in Lebanon, Hezbollah has sought to contain tensions in Lebanon. Together with its allies of the March 8 Alliance it aims to deter supporters of the Syrian opposition from using Lebanon to channel support for the Syrian opposition.

According to the International Crisis Group the Syrian crisis is of immense strategic interest for the Sunni-dominated Future Movement, since it would represent the beginning of the end for the Syrian regime – in the process weakening the position of its main opponent Hezbollah. The Future Movement has expressed political solidarity with the Sunni-dominated Syrian opposition and adopted a strong rhetorical stand against the regime, while – like Hezbollah – at the same time objecting to the use of Lebanon as a platform to assist the opposition.

The March 14 Alliance pointed fingers at Syria after the killing of security chief Wissam al-Hassan in October 2012 and demanded the Mikati government to step down, claiming that he had given the Syrian regime political cover. Hezbollah did not adhere to opposition calls for a new government. Safeguarding the government, with eighteen of its ministers from the March 8 Alliance, was of vital interest.

In 22 March 2013, Prime Minister Najib Mikati announced his resignation, citing the parliament’s refusal to extend the tenure of Ashraf Rifi, the national police chief and a supporter of the March 14 Alliance, a coalition of political parties supportive of the opposition in Syria. This has weakend March 14 Alliance and gave Syria’s regime allies in the March 8 Alliance the opportunity to appoint a politician sympathetic to their cause.

On 6 April 2013, Tammam Salam was named prime minister and tasked with forming a new government. However, no candidate reached a two-thirds majority vote in the first round, and subsequent rounds failed to gain a quorum. In the midst of a political gridlock, the elections were postponed until June 2017.

The Military

Since the withdrawal of Syrian troops from Lebanon in 2005, the Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF) have become an increasingly professional and capable national military institution.

This is no mean feat in a country where competing sectarian political parties have devised a delicately balanced political system leaving them stronger than state institutions. Moreover, amid a wave of popular uprisings over a worsening economic situation as well as electricity and water shortages, the LAF is seen as the only institution stabilizing the country.

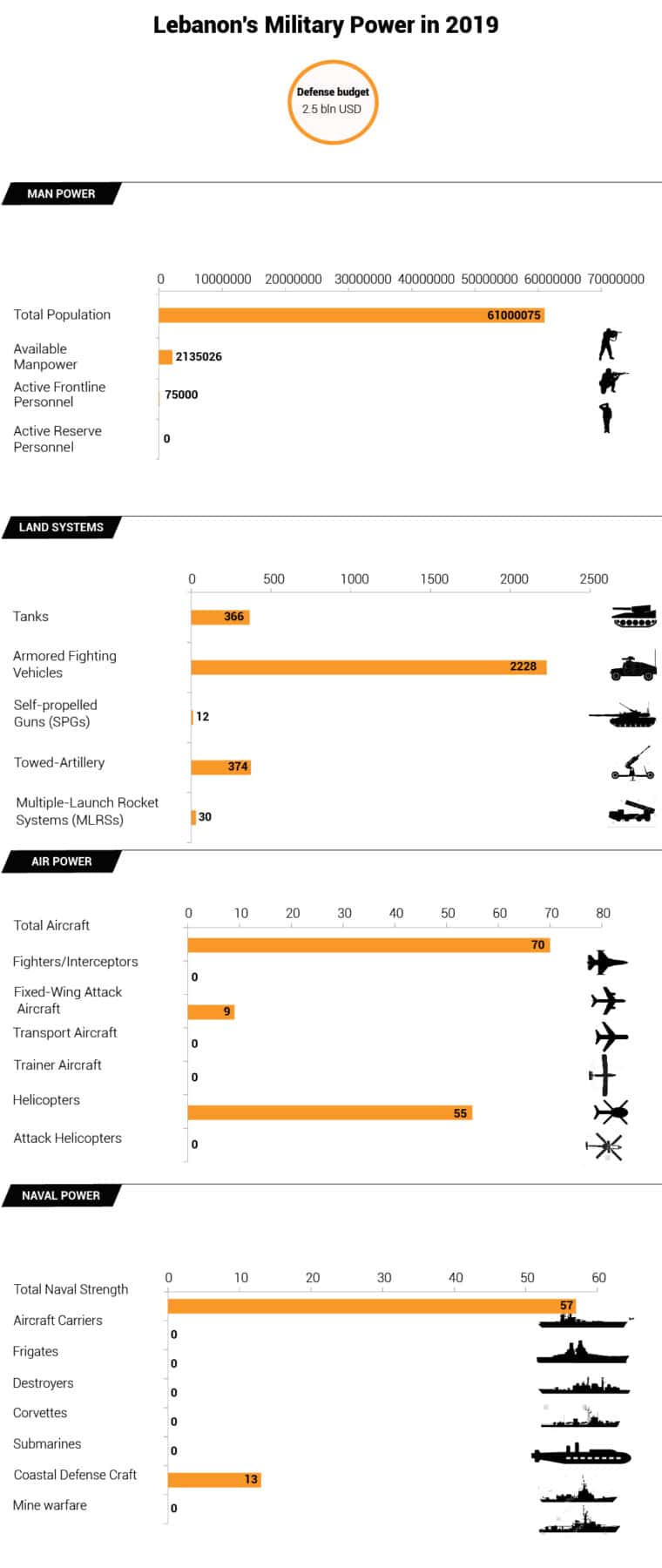

In 2019, Lebanon ranked 118 out of 137 countries included in the annual GFP review. That year, the number of people who reached military age was estimated at 68,775 personnel, while military expenditure was estimated at $1.7 billion. In 2018, military expenditure accounted for 5 per cent of GDP, compared with 4.6 per cent in 2017 and 5.2 per cent in 2016, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

| Index | Number | Rank out of 137 |

| Total military personnel | 75,000 | - |

| Active personnel | 75,000 | - |

| Reserve personnel | 0 | - |

| Total aircraft strength | 63 | 81 |

| Fighter aircraft | 0 | 137 |

| Attack aircraft | 0 | 137 |

| Transport aircraft | 3 | 51 |

| Total helicopter strength | 5 | 86 |

| Flight trainers | 13 | 69 |

| Combat tanks | 276 | 56 |

| Armoured fighting vehicles | 2,330 | 32 |

| Rocket projectors | 30 | 50 |

| Total naval assets | 57 | - |

Lebanon’s military strength in 2019. Source: GFP review.

Defence budget

USD 650 million (2007)

Active military personnel

62,000, including 2,000 conscripts

- Army 60,000

- Navy 1,000

- Air force 850

Main Battle Tanks (MBT)

About 300; two thirds are old Soviet T-54/55,

the remainder are modernized M-48A5

and a few dozen ex-Belgian Leopard I’s

Armoured Patrol Cars (APC) +

Armoured Infantry Fighting Vehicles (AIFV)

1000+ American M-113

Surface combatants

A handful of coastal and inshore patrol craft, two landing craft

Combat aircraft

Three dozen American and French utility helicopters, some lightly armed

From the list of small arms currently in service with the Lebanese army, one can immediately sense this is not a properly equipped and functioning army: American M-16, CAR-15 and Colt M-4, Russian AK-47, AK-74, AKS-74, and AKM-59, German MP-5 and HK G3, Belgian P90 and MAG.

The list is even incomplete. This miscellaneous weaponry must present considerable challenges in the field of training and logistics. That is to say, if the Lebanese army were a coherent fighting force. But the army – like the country – is divided along religious fault lines and has consequently been toothless since the country’s independence in 1943.

Nevertheless, since a whole Shiite brigade deserted in 1984 to Amal and another, this time a Druze formation of the regular army, dissolved and changed sides to join a Druze militia, things have improved markedly.

During recent crises the armed forces have managed to at least give the impression of the army as a national institution, with the exception of the clashes in May 2008 when armed forces stood by, so as to avoid any risk of internal splits.

In 2005, after the assassination of former Prime Minister Rafic Hariri, the Syrian occupying forces withdrew from Lebanon as a result of external pressure, especially from France and the United States. As the importance of the Lebanese forces grew accordingly, the US shipped sizable quantities of modern equipment to the country. For example, 285 American Hummers and modern French anti-tank missiles were supplied.

Readiness has also improved. In 2006, after the war between Hezbollah and Israel, the Lebanese army deployed 15,000 troops in the south of the country where they, in close cooperation with the same number of United Nations observers, kept – and still keep – an eye on the security situation. In the 2007 conflict with Fatah al-Islam, a Sunni Palestinian faction, which had set up base in Nahr al-Bared, and was said to have links to al-Qaeda, the Lebanese Army emerged victorious. Yet their losses (170) were relatively large compared to the modest force of insurgents (a couple of hundred), and it took the military a month to neutralize them.

In August 2016, the US has supplied huge quantities of equipment to Lebanon. This includes 50 armoured vehicles, 40 pieces of artillery and 50 launching platforms, as part of a support package worth more than $220 million.

Lebanese Air Force

The Lebanese Air Force is only a shadow of its former self. In the 1960s it had at its disposal a dozen French Mirage III fighters, which were considered modern and capable at that time. To draw a comparison, in the same period the formidable Israeli Air Force flew with the same type of aircraft, which proved superior to the MiGs and Sukhois of the Syrian and Egyptian air forces. A handful of vintage Hawker Hunters were also in service.

However, in the 1970s the Mirages were sold to Pakistan, and the Hunters, which had been bought in the late 1950s and early 1960s, were mothballed in the 1980s due to a lack of pilots and ground personnel. In 2007, the Hunters were taken out of storage to perform bombing missions against Fatah al-Islam insurgents. A few have even been taken into operational service again. Nevertheless, it seems that the service life of these museum pieces cannot be extended indefinitely.

That is not to say the Lebanese Air Force has ceased to exist all together. For example, it is worth noting that the inventory of helicopters – three dozen Hueys and Gazelles – is relatively large in relation to the number of personnel.

Lebanese Navy

The Lebanese Navy, consisting of several dozen, mostly inshore patrol craft and two landing craft, is deployed at modest bases in Beirut, Jounieh and some naval stations in Tripoli and Tyre. According to the American think tank CSIS: ‘Given its scarce resources and manpower, the Lebanese Navy has a limited coastal patrol capability and some troop lift capability but no real war-fighting capability against Israel or Syria. It can perform a surveillance role, inspect cargo ships and intercept small infiltrating forces, but only along a limited part of Lebanon’s 225-km coastline.’

Latest Articles

Below are the latest articles by acclaimed journalists and academics concerning the topic ‘Politics’ and ‘Lebanon’. These articles are posted in this country file or elsewhere on our website: