Administration and Politics

The Republic of Turkey was founded in 1923, following the Ottoman Empire’s defeat in World War I and the subsequent Turkish War of Independence led by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk. As the first president of the new republic, Atatürk initiated a program of political, economic, and cultural reforms, which became known as secular Kemalism, to build a ‘new Turkey’ that was far from its Ottoman and Islamic heritage.

Atatürk’s Republican People’s Party became the dominant political organization of a one-party state until World War II. Despite transitioning to a multi-party system after the war, Turkey’s political system faced numerous difficulties, including three military coups between 1960 and 1980. In February 1997, in what was dubbed a ‘post-modern coup’ because no soldiers were involved, the military engineered the resignation of Prime Minister Necmettin Erbakan, the Islamic leader Welfare Party, for what it saw as the government’s growing religious activities.

The political balance of power has since evolved into a state where military coups seem a thing of the past. Since 2002 the moderate Islamist AKP has governed Turkey successfully. To date, the long, drawn-out conflict with the Kurdish national movement remains unresolved, although significant shifts seem to be taking place.

In July 2016, a failed attempt was made to overthrow President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. The ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) accused the influential preacher Fethullah Gülen and his Hizmet (or ‘service’) movement, which has been described as a ‘parallel state’ inside Turkey, of the coup attempt. In the months that followed, tens of thousands of people believed to be members of the Hizmet movement were arrested.

In a referendum held on 16 April 2017, 51.4 percent of Turks voted in favor of wide-ranging constitutional amendments, transforming Turkey from a parliamentary republic to a presidential one.

Turkey was sharply divided over these amendments. Whereas Erdoğan supporters argue that they will improve the executive branch’s effectiveness, opponents believe they will grant Erdoğan sweeping new powers that will undermine the democratic process.

The Presidency

The election of former President Abdullah Gül (President from 2007-2014), which was strongly opposed by the Army and Kemalist circles in 2007, showed how politically important presidential elections are. Gül’s two predecessors, Süleyman Demirel (born 1924) and Ahmet Necdet Sezer (born 1941), were the symbolic protectors of a political coalition with the Army.

Sezer often opposed the laws adopted by the Grand National Assembly of Turkey and the government’s nominations of then Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. With the election of Gül, a first lady wearing a headscarf for the first time entered Çankaya Palace, which is considered one of the Kemalists’ sacred fortresses.

The current President of the Republic is Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, voted in as President on 10 August 2014. Erdoğan, who was Prime Minister from 2003 to 2014, paved the way for a presidential system similar to the American and Franco-Russian model.

Despite the Gezi protests in May-June 2013, allegations of corruption against Erdoğan, his family, and members of his government—as well as a bitter power struggle between the government and the followers of Pennsylvania-based religious leader Fethullah Gülen—the opposition proved unable to stop Erdoğan’s march to the Presidency.

Ekmeleddin Ihsanoğlu, the candidate, fielded jointly by the Republican People’s Party (CHP) and the right-wing National Movement Party (MHP), garnered only 38.4 percent of the vote. Selahattin Demirtaș, representing the People’s Democratic Party (HDP), won just under 10 percent of the vote, which was a strong result, at the national level, for a politician associated with the Kurdish movement.

As the head of the state and the Army, the President does not have executive authority in the strict sense of the word; rather, he has great symbolic authority. However, before the 2014 Presidential election, Erdoğan stated clearly that he did not intend to limit himself to his predecessors’ largely ceremonial role. His focus was on the general elections that were held by June 2015.

To change the constitution and officially grant the presidency the executive powers Erdoğan sought, the government secured the backing of at least two-thirds of the next parliament members. In snap elections in November 2015, the AKP was able to secure the necessary seats in parliament to hold a referendum on Erdoğan’s proposed amendments to the constitution.

The new constitution, which will be implemented after presidential and parliamentary elections scheduled for November 2019, will see the role of prime minister scrapped and make the president the head of the executive and the head of state while allowing him or her to retain ties to a political party.

The president will also be given new powers to appoint ministers, prepare a budget, choose the majority of senior judges, and enact certain laws by decree. The president will also assume the army’s leadership, and he or she alone will be able to declare a state of emergency. A presidential term will be set at five years, and the president will be limited to two terms.

The Executive

After the transition to a multi-party system, the prime minister and the Council of Ministers supervised the executive branch. The president is the head of state and represents the Republic of Turkey and the Turkish nation’s unity.

The prime minister, who, until the referendum in April 2017, was appointed by the president, was often the leader of the largest party in parliament and responsible for supervising government policy implementation. Following the vote in favor of constitutional amendments, the prime minister’s role will be scrapped, and the president will assume the prime minister’s executive powers. Binali Yildirim has been prime minister since May 2016. He replaced Ahmet Davutoğlu, who assumed the position in August 2014 but fell out with Erdoğan over the proposed referendum.

During his era as a prime minister, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan (born 1954) headed the executive branch. He received diplomas from a school to train imams and preachers and from the School of Economics and Commercial Sciences. He was mayor of Istanbul from 1994 to 1998 and was imprisoned for four months in 1999.

In 2001, he established the Justice and Development Party, following a split in the Islamic movement led for a long time by engineer Necmettin Erbakan (1926-2011). Even though his authority was not challenged by the party of which he was the charismatic pillar, Erdoğan ran a government that was home to many orientations, ranging from the ultranationalism of Minister of Interior İdris Naim Şahin (born 1956) to the liberalism of deputy Prime Minister Bülent Arınç (born 1948).

As a result of the Army’s weakening after 2007, when many of its senior officers were imprisoned, and the Constitutional Court, which acted as a censorship authority in many legal and legislative domains between 1980 and 2000, the executive body came to wield vast authority.

Turkey experienced several periods during which only one party was in power: the Republican People’s Party of İsmet İnönü, between 1946 and 1950; the Democratic Party of Adnan Menderes, between 1950 and 1960; the Justice Party of Süleyman Demirel, between 1965 and 1971; and the Motherland Party of Turgut Özal, between 1983 and 1991.

During the 1970s and 1990s coalition governments were often weak, leaving the Army with much room for manoeuvre. The internal fragmentation of the Turkish political space in the 1990s is one of the factors that enabled the Justice and Development Party led by Erdoğan to sweep to power, by winning most of the votes, with an increase from 34.6 percent in 2002 to 49.9 percent in 2011.

The Legislative

The legislative branch, by a motion of confidence by the deputies, is the government’s main source of authority.

The Grand National Assembly of Turkey, established in 1920 on the model of the Chamber of Deputies of the Ottoman Empire, has the power to conduct independent investigations which it deems necessary and may also propose draft laws and, with a three-quarters majority, amend the Constitution following a decision of the Assembly.

In June 2012, the 550 seats in the Grand National Assembly were held by 326 deputies of the Justice and Development Party, 135 of the Republican People’s Party (social democratic), 51 of the Nationalist Movement Party (far-right), 29 of the Peace and Democracy Party (Kurdish), and 7 independents. Two seats remain vacant. The President of the Republic may veto, only once, a law passed by the Assembly and is entitled to submit a claim to the Constitutional Court in case of a continuing dispute.

The constitutional amendments voted for in the referendum represent a pivotal moment in the history of Turkish politics. According to these amendments, which will become effective after parliamentary and presidential elections in November 2019, the number of MPs will increase from 550 to 600. The age of candidates eligible to run in elections will be lowered from 25 to 18. A parliamentary term will be increased from four years to five.

Parliament will lose its right to scrutinize ministers or propose an inquiry. However, it will begin impeachment proceedings or investigate the president with a majority vote by MPs. Putting the president on trial would require a two-thirds majority. The president will have the power to dissolve parliament and call new elections.

Parliament will also have the power to call elections, providing three fifths of its members agrees. The parliamentary positions of members who are appointed as vice-president or minister will be dropped.

Erdoğan’s proposed constitutional changes have been one of the most divisive issues in recent Turkish politics. In the general elections held in June 2015, the AKP, for the first time in its history, failed to secure an outright majority in parliament, winning only 40.8 percent of the vote (258 of the 550 seats). This also put it below the 367-seat threshold needed to change the constitution directly, and the 330 seats needed to call a referendum to change the system.

Against the backdrop of a hung parliament and the AKP’s failure to form a coalition, Erdoğan called a snap election for 1 November 2015. This election resulted in the AKP regaining its parliamentary majority, winning 49.5 percent of the vote and 317 seats. In contrast, the Republican People’s Party won 25.3 percent of the vote (133 seats), the Nationalist Movement Party 11.9 percent (36 seats), and the People’s Democratic Party 10.7 percent (58 seats). Independent candidates won five seats.

The Legal System

European models influence the legal system in Turkey. It comprises the Constitutional Court (Anayasa Mahkemesi, seventeen members appointed by the President of the Republic and the Grand National Assembly) with vast censorship powers, the Turkish Council of State (Danıştay), the Court of Cassation (Yargıtay), and the Turkish Court of Accounts (Sayıştay), as well as superior courts and courts of the first instance. It distinguishes criminal-law judges from civil-law judges and from federal-law judges in charge of enforcing the corporate law.

The justice system is generally independent, it is also highly politicized and manipulated by ideology, and it is possible to interpret restrictive laws in a more or less repressive way. For example, 12,897 of the 35,117 people convicted worldwide of ‘terrorist crimes’ between 2001 and 2011 were in Turkey. In the Turkish case, ‘terrorist’ refers to demonstrating students, Kurdish mayors, university professors, and journalists. Courts often tried these accused with special jurisdiction. The abolition of such courts is currently being studied.

The Turkish legal system owes its origins to the administrative reforms of the Tanzimat (‘Reorganizations’) of 1839-1876, the codification undertaken by Cevdet Pasha (1822-1895), during the reign of Abdülhamid II, and the radical reforms that took place at the beginning of the Kemalist Republic, under the leadership of Mahmud Esad Bozkurt (1892-1943), Minister of Economy and then Minister of Justice, who strongly opposed the separation of executive, legislative, and judicial powers.

The main legal documents of the Kemalist Republic were the 1924 Constitution, the Civil Code of 1926 – considered a conservative adaptation of the Swiss Civil Code – and the penal code inspired by that adopted by Fascist Italy at the time. Although the Constitution was thoroughly modified in 1961 and 1982, these documents were modified little in principle and constrained the Turkish legal space until the end of the 1990s.

The associate membership of Turkey in the European Union and the 2010 referendum amending several articles of the Constitution have provided some relief from the repressive measures of the legal system, both civil (equal status and shared responsibility within families) and penal (removal of many articles restricting freedom of expression and granting total immunity to the military).

These reforms, however, did not allow complete liberalization: Article 301 of the Penal Code criminalizes ‘insults to the Turkish nation’ (which can be charged whenever the subject of the recognition of the Armenian genocide is raised), and the anti-terrorist law may lead to the charges against virtually any dissident.

Regardless of the nature of the legal texts, control over the state’s agents remains insufficient: thousands of violations of human rights, many of which are attributed to the state, were reported by Human Rights Watch. The Diyarbakır branch of the Human Rights Association (İnsan Hakları Derneği) reported on 4 June 2012 that 171 children were killed during the ten-year rule of the Justice and Development Party.

Finally, even though Turkey has, since the end of the Kemalist rule, stipulated a separation of powers and granted – except during some periods – independence to judges, it has failed to limit the arbitrary power of justice.

As illustrated by the lawsuits against Professor Muazzez İlmiye Çığ, a nonagenarian specialist in the ancient civilizations of Anatolia and Mesopotamia, and the novelist Nedim Gürsel, both of whom were accused of insulting moral values and religion, and Orhan Pamuk, a Nobel Prize-winning novelist who was prosecuted several times, many prosecutors and judges interpret the law in a very repressive way, even though the executive may not influence them.

The latest example of these powerful legal interventions is the prosecution of world-famous pianist Fazıl Say in 2012 over his Twitter posts mocking Islam. There are also hundreds of Kurdish elected members who have been arrested or prosecuted in the last decade.

Turkey has adopted most of the international conventions on transparency, the rights to petition and to access information, and equal treatment of ‘nationals’ and ‘foreigners.’ It has also signed the Vienna Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods, thus recognizing the possibility of resorting to the law of the country of the foreign contracting party in case of a dispute. Turkey has ratified various conventions on protecting patents and authors’ and artists’ rights (although illegal copying continues on a vast scale).

The constitutional amendments that were approved in April 2017 will see the abolition of military courts, including the Supreme Judicial Military Court and the Supreme Administrative Military Court. It will also be prohibited to form military courts, with the exception of what are described as ‘disciplinary courts’.

Local Government

As a highly centralized country, Turkey does not grant local autonomy to its provinces. The central authority has always rejected attempts to transition to a federal system, which appeared to have been gaining the support of the former President, Turgut Özal.

However, municipalities that had always been under the direct control of Ankara gained some autonomy in the 1970s and became the subject of political battles, sometimes bloody, between various parties or local dynasties. The autonomy of municipalities increased with the reforms of the 1980s and 1990s.

The number of municipalities increased from 467 in 1929 to 544 in 1947, 862 in 1956, and 1,062 in 1965. The number of municipal employees increased from 5,180 in 1932 to 45,132 in 1964 and reached a peak in the 1970s. Currently, municipalities have around 260,970 employees, while the central government employs 2,029,185 (excluding state enterprises, which employ more than 450,000).

Following the establishment of sixteen greater municipalities, the local authorities have become independent entities with large budgets (for example, USD 3.7 billion was allocated to Istanbul, USD 470 million to Bursa, and USD 76 million to Manisa). Municipalities in the Kurdish regions, which had been largely under the control of the Kurdish Peace and Democracy Party, gained real autonomy, but at the cost of the arrest of several mayors.

Political Parties

The history of political parties in Turkey is complicated and painful: political crises caused the fragmentation of these parties, and military regimes or the Constitutional Court banned several of them. Following the 1960 coup d’état, several politicians were given long prison sentences or were assassinated.

There are currently 22 active parties in Turkey, but the threshold to gain seats in the Parliament is ten percent of the votes cast (on the electoral-district level nationally), so only four parties hold seats in the Grand National Assembly. Hamit Bozarslan describes these parties as follows:

The Justice and Development Party

The Justice and Development Party (AKP) was established in 2001 from the Islamist Virtue Party’s faction, which the Constitutional Court dissolved. It won three consecutive legislative elections in 2002, 2007, and 2011, thus gaining a dominant Turkish political life position. The party is politically conservative and economically liberal. President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan was the leader of the party between 2001 and 2014. Ahmet Davutoğlu, between 2014 and 2016, succeeded him. Until the referendum, the AKP party leader was Prime Minister Benali Yildirim. In May 2017, Erdoğan returned the ruling party’s chief in a special party congress convened for re-electing him.

The Republican People’s Party

The Republican People’s Party was established by Mustafa Kemal (Atatürk) (1881-1938) in 1923 and played a central role in founding the republic in 1923 and establishing the single-party system in 1925. Having merged with the state in 1937, the party was obliged to accept political pluralism in 1945.

After the death of Mustafa Kemal in 1938, the party was led by İsmet İnönü (1884-1973) and then by Bülent Ecevit (1925-2006). The party experienced a major internal crisis between 1980 and 2000, especially under the leadership of Deniz Baykal (born 1938) and Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu (born 1948). The party is supported by about 25 percent of the voters, reportedly including many Alevis.

The Peace and Democracy Party

The Peace and Democracy Party was established to replace the People’s Labour Party founded by Turkish and Kurdish left-wing activists in 1990. This was the first ‘pro-Kurdish party with parliamentary representation, but the Constitutional Court banned it. Earlier parties – the Democracy Party (DEP), the People’s Democracy Party (HDP), the Democratic People’s Party (DHP), and the Democratic Society Party (DTP) – were often severely suppressed and were also banned. The Peace and Democracy Party (founded in 2008) later formed a parliamentary group.

The Nationalist Movement Party

The Nationalist Movement Party was established in 1969 by Colonel Alparslan Türkeş (1917-1997) by changing the name of a party he used to lead (Republican Villagers National Party) to the NMP. This party has always been the principal political focal point for Turkish ultranationalism. With the help of the Ülkü Ocakları (Hearths of the Ideal) network and the support of a group of voters in the Central Anatolia Region and the coastal regions, Devlet Bahçeli took charge of the party after the death of its founding başbuğ (chief/commander) in 1997.

There are many right- and left-wing parties, such as the Felicity Party (Islamist), the neo-nationalist (Ulusalcı) camp (‘nationalist’, Kemalist, and secularist), and illegal radical left-wing parties.

The Military

Army ceremony commemorating the Battle of Gallipoli in Canakkale, in 2012 / Photo Shutterstock

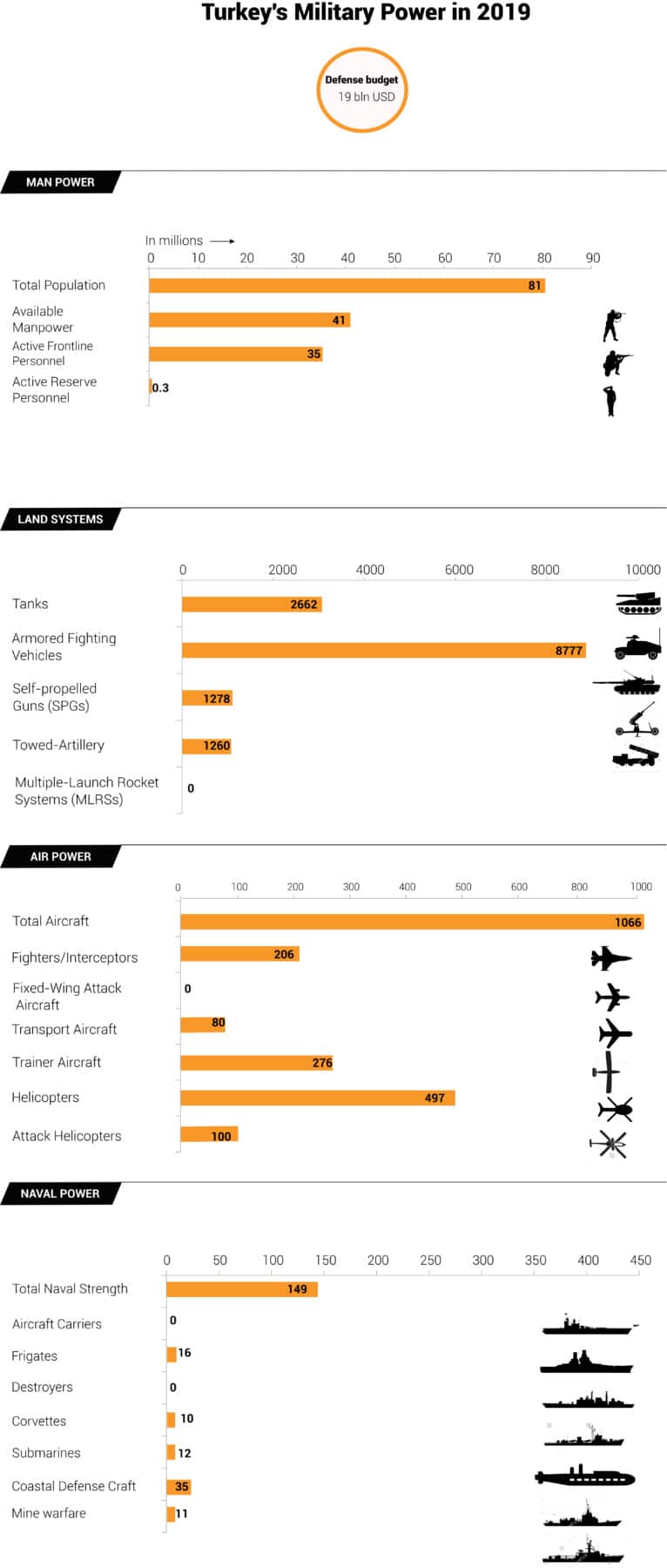

Regarded as the strongest military force in the MENA region, Turkey continues its march towards developing a mature military industry to help satisfy standing local requirements.

In 2019, Turkey ranked 9 out of 137 countries included in the annual GFP review. That year, the number of people who reached military age was estimated at 1.4 million personnel, while military expenditure was estimated at $8.6 billion. According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, in 2018, military expenditure accounted for 2.5 percent of GDP, compared with 2.1 percent in 2016 and 2017, according to Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

From 1908 until the beginning of 2010, the military institution – as a single corps or as groups of dissident officers – played a central role in the Ottoman and Turkish political system.

In July 1908, the revolution of the officer members of the Committee of Union and Progress in Macedonia, who threatened to advance on the capital, led to the restoration of the Ottoman constitution that had been suspended since 1877.

| Index | Number | Rank out of 137 |

| Total military personnel | 735,000 | - |

| Active personnel | 355,000 | - |

| Reserve personnel | 380,000 | - |

| Total aircraft strength | 1,067 | 10 |

| Fighter aircraft | 207 | 14 |

| Attack aircraft | 207 | 14 |

| Transport aircraft | 87 | 8 |

| Total helicopter strength | 492 | 8 |

| Flight trainers | 289 | 9 |

| Combat tanks | 3,200 | 7 |

| Armoured fighting vehicles | 9,500 | 7 |

| Rocket projectors | 350 | 12 |

| Total naval assets | 194 | - |

| Frigates | 16 | - |

Turkey’s military strength in 2019. Source: GFP review.

A year later, the Army of Action, which was formed in the Balkans, bloodily suppressed the ‘counter-revolution’ of the enlisted men against their senior officers in Istanbul and led to the deposition of Sultan Abdülhamid II.

The third of this series of military interventions was carried out by the Committee of Union and Progress officers. They organized a coup d’état after the defeat of the Ottomans in the First Balkan War (25 January 1913), leading to the establishment of a single-party system ruled by a triumvirate consisting of Talaat Pasha (1874-1921), the minister of interior (and the prime minister as of 1916), Djemal Pasha (1872-1922), the minister of marine, and Enver Pasha (1881-1922), the minister of war.

The Ottomans’ defeat by the Allied forces in the First World War resulted in the almost destruction of the army and private militias.

Following their defeat, the Ottomans signed the Treaty of Sèvres, which abolished the Ottoman Empire and obliged it to renounce all Arab Asia and North Africa rights. The treaty also provided for an independent Armenia and an autonomous Kurdistan.

The new Turkish nationalist regime, led by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, rejected the treaty and launched the Turkish War of Independence against the treaty’s armies.

This resulted in the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne, in which Turkish sovereignty was preserved through the establishment of the modern-day Republic of Turkey.

A side-effect of the war was creating a centralized state that relied on the army for its authority. The army came to play a decisive role in Turkish politics and considered itself the ‘protector of secularism and Atatürk’s way.’

Although Turkey introduced party pluralism after the Second World War, this did not prevent several illegitimate military committees from being formed, nor three military coups being carried out in the ’60s, ’70s and ’80s. The army continued to play a significant role in politics until 2002 when the Justice and Development Party (AKP) came to power.

The Turkish Army, with nearly 600,000 men, includes a professional officer corps trained in military schools and draftees (military service is compulsory, and people are not allowed to declare themselves conscientious objectors). The Army includes ground forces (in four forces, headquartered in Istanbul, Malatya, Erzincan, and the Aegean Region; it consists of ten corps), Air Forces (concentrated in Eskişehir and Diyarbakır), naval forces, and the gendarmerie of the Ministry of Interior.

The defense staff chief does not report to the minister of defense, so the army has always been completely autonomous, managing its own business, promotions, and purges. This autonomy is now being restricted, and the army no longer plays a direct political role. However, it does play a major role in national security. It is considered one of the country’s five main economic powers, thanks to OYAK, the Army Mutual Aid Association.

In 2001 the army established the government of the Justice and Development Party (AKP), a conservative Islamist party that came to power in 2002 and faced constant pressure before losing the battle for dominance in 2007. The discovery of tens of thousands of documents that proved the army’s preparations for abortive coups d’état caused a great stir in public opinion; this was an unprecedented event in Turkey’s history and led to the arrest of many generals some of whom are still in prison.

Under the AKP, the influence of the army has been systematically reduced. The failed military coup in July 2016 is perhaps emblematic of this. The AKP accused the army of coordinating the coup attempt with the Fethullah Gulen movement, described as a ‘parallel entity.’

According to some experts, the Turkish army became a ‘broken power’ after the coup attempt. In its aftermath, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan arrested some 360 army generals and dismissed and arrested thousands of military personnel and government employees. He also vowed to overhaul the army to give it “fresh blood.”

In terms of armament, the army relies on imported weapons, particularly from the United States, Germany, and China, although it does manufacture some locally.

In January 2017, Turkey signed a $110 million deal with Britain to manufacture TF-X fighter planes. In March the same year, Turkey entered into negotiations with Russia to purchase the S-400 rocket defense system. ِArms deals with Germany ran into complications following the failed coup attempt and subsequent widespread arrests, with Berlin rejecting ten requests by Ankara to purchase weapons.

Latest Articles

Below are the latest articles by acclaimed journalists and academics concerning the topic ‘Politics’ and ‘Turkey’. These articles are posted in this country file or elsewhere on our website: