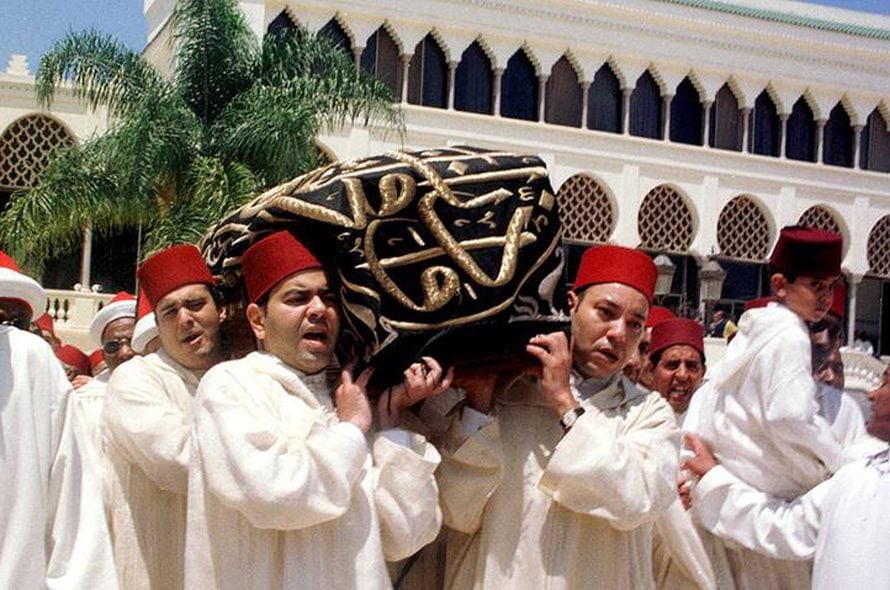

Hassan II’s funeral in 1999 was attended by a new Jordanian King, a new Emir of Bahrain, a new President of Algeria, and a new Prime Minister of Israel. Shortly afterward, President Hafiz al-Assad of Syria died and was succeeded by his son, Bashar al-Assad; Mohammed VI was part of a new generation in the Arab states, but twelve years later, that new generation was stumbling through the Arab Spring.

Like his father, Mohammed VI had studied law in France, but he had never held a military command or executive position. He talked of continuity, but he framed it in terms of giving real shape to the theoretical promises of constitutional monarchy, political pluralism, law, and human rights. In his personal life, he personified modernization. His father’s wives were kept almost entirely secret, but the new King’s marriage to Salma Bennani was public. She was well-educated in information technology and attractive, the face of the new Moroccan woman.

The new King moved quickly on human rights: he released political prisoners, allowed exiles to return, and sacked Driss Basri, the sinister Minister of the Interior. Many buried human-rights scandals resurfaced, prominent among them the fate of Mehdi Ben Barka and the vicious treatment that had been meted out to General Oufkir’s family, several members of which wrote books recounting their experiences. Other former prisoners revealed what had happened in the secret prison in Tazmamart, in the Atlas Mountains, where officers accused of taking part in the 1970s coups d’état had been imprisoned for years. By 2004, the political pressure on human-rights abuses in the past had become so great that Mohammed VI established an Equity and Reconciliation Commission to investigate abuses, rehabilitate the victims, and pay them compensation. But there were strict limits to its actions: no one could be prosecuted, and abuses perpetrated after Mohammed VI came to the throne could not be mentioned.

Other apparently liberal trends were also held in check: newspapers and magazines continued to be censored and banned, and the Saharan war, in particular, remained off-limits for criticism. Attempts have been made to reign in the high level of corruption in the administration, but these have been checked by the involvement of the monarchy in the private sector and the determination of members of the elites not to be called to account.

The War on Terror was another reason that civil-rights legislation has not been followed through on: in 2003, several bombs went off in Casablanca killing 33 people, and there were another twelve suicide bombings. Some of the targets were international hotels and restaurants; others were Jewish sites.

The regime attempted to change the status of women by rewriting the family-law code. In 2004 the King imposed a new Mudawana. This brought major changes to the status of women but in the context of giving the King the main oversight over the position of women. It was met with fierce protests by Islamist opponents, who mobilized huge demonstrations against it, and linked it to government relations with Israel. In January 2010, King Mohammed VI set up the Consultative Commission on Regionalization to report on how local and regional administration might be managed, apparently with the aim of providing a framework to solve the Western Sahara dispute by offering that region considerable autonomy.

In short, the democratization process stalled. One fundamental fear was that illiberal forces would benefit most from the political opening, that it would limit the power of the state to hold terrorists in check if the system was open to wider criticism. And there were powerful constituencies that opposed democratization. Finally, the King seems to have decided that socio-economic development was more important than political reform and that the regime would succeed or fail on the basis of its ability to promote growth and reduce unemployment and poverty.

To some extent, the emphasis on economic development served the regime well, but economic growth over the first decade of the 21st century was not enough to hold the protests in check during the Arab Spring. On 20 February 2011, a youth group, the February 20th Movement for Change, appeared on Facebook and organized demonstrations across the country. These brought together people from a wide range, including liberal youth, leftists, and Islamists from the banned Justice and Charity movement. The protests were not directed against the King; their target was the need for a genuine constitutional monarchy, the dismissal of Prime Minister Abbas al-Fassi, and elections.

The King responded by setting up a Constitutional Reform commission, whose members he chose. He promised a new Constitution to strengthen Parliament, increase the independence of the judiciary, and provide greater regional and local power. The new Constitution was prepared quickly and approved in a referendum on 1 July 2011. It incorporated the recommendations that would allow regional autonomy, although these have not yet been put into effect. It strongly emphasizes human rights and rights of citizenship and makes Berber an official language, but power remains firmly in the King’s hands. Nevertheless, it allows activists to press for more real reforms and a genuine constitutional monarchy.

Most importantly it led to elections in November 2011, in which the moderate Islamist Party of Justice and Development emerged as the largest party, and Abdelilah Benkirane, its leader, became the new Prime Minister, heading a coalition with Istiqlal, the Popular Movement and the Party of Progress and Socialism. (See also Political parties.)