Introduction

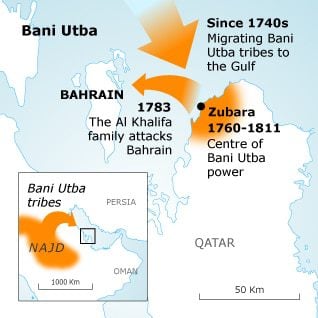

Bahrain is a monarchy, ruled since 1783 by the Al Khalifa family. At its apex stands King Hamad, who came to power in 1999. Since his accession, he has been engaged in a power struggle with his uncle Khalifa bin Salman Al Khalifa, Bahrain’s Prime Minister since 1971.

Bahrain’s political structure resembles that of the other Gulf Cooperation Council states in some key ways. Members of the ruling family control the sovereign ministries (Defence, Interior, Finance, and Foreign affairs), and other ministries are headed by ruling-family members or technocrats.

There have been only modest attempts at political liberalization, and, since 2011, the reformist camp, led by Crown Prince Salman, has been overshadowed by the hard-line camp, led by Prime Minister Khalifa bin Salman.

The Monarchy

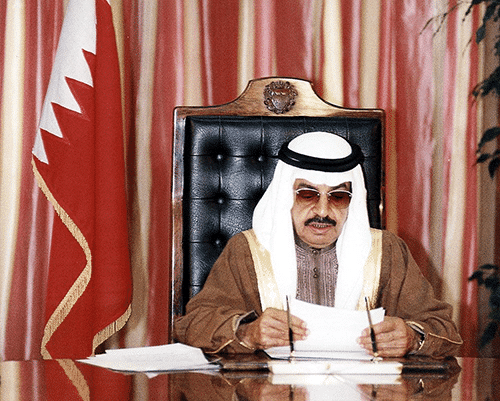

Bahrain is a monarchy, ruled by King Hamad bin Isa Al Khalifa, who came to power in 1999 following the death of his father, Emir Isa bin Salman Al Khalifa. Bahrain’s monarchy is roughly similar in political form to the dynastic monarchies of the other Gulf Cooperation Council states. The monarch rules with the assistance of his relatives who occupy the most important (or sovereign) ministerial posts, such as Defence, Interior, and Foreign affairs.

After taking power, Sheikh Hamad initially took steps in the direction of a constitutional monarchy. Bahrain’s original Constitution, promulgated in 1973, had been suspended since 1975 after a period of political unrest.

In 2001, Sheikh Hamad put forward a new National Charter and the following year a new Constitution was promulgated. However, in 2002 Sheikh Hamad also transformed Bahrain from an emirate to a kingdom, giving himself the title of King.

In the following years, the moves toward reform slowed. By 2012 the Crown Prince, Sheikh Salman bin Hamad Al Khalifa, considered by many to be more of a reformist than the king, had been largely been marginalized following his attempts to negotiate an end to the political crisis in 2011. He was largely eclipsed by the more hardline Prime Minister, Sheikh Khalifa bin Salman Al Khalifa.

The Executive

While King Hamad is the head of state, he shares some power with his uncle, Bahrain’s Prime Minister, Sheikh Khalifa bin Salman Al Khalifa. Sheikh Khalifa is the world’s longest-serving prime minister, having been in office since 1971. He has historically and, most recently during the Arab Uprising of 2011, been associated with a hardline response to protesters. One of the leading demands of the opposition during the protests of 2011 was to replace the Prime Minister with an elected official.

The Legislative

Government policy comes from the King and his close family members. However Bahrain also has a bicameral legislature, the National Assembly, consisting of the appointed consultive Shura Council (established in 1992) and the elected Council of Representatives, each with forty members, serving four-year terms. The National Assembly’s powers are modest. It has only a limited ability to draft laws and has no input into the composition of the government.

The appointed Shura Council can block legislature from the elected Council of Representatives. One of the demands put forward by the opposition in 2011 was for a unicameral legislature with real legislative powers. The size, shape, and composition of the forty electoral districts that provide representatives led to opposition accusations of government gerrymandering with the goal of favoring the Sunni population.

The National Assembly was Bahrain’s second attempt at participatory government. Bahrain experienced a brief electoral experiment following independence. In 1972 a Constituent Assembly was elected to draft the state’s first Constitution following in 1973 by elections for a unicameral National Assembly. However, after the elected legislature proved too independent for the ruler, objecting in particular to the government’s new state of emergency law, the government shut the legislature down.

After Sheikh Hamad took power, the experiment was revived. A National Action Charter was adopted in 2001, followed by the ratification of a new Constitution in 2002. This Constitution, however, was significantly less democratic than the National Action Charter.

Elections

Elections for the new National Assembly were held in 2002, 2006, 2010 and 2014. The first round of elections in 2002 were boycotted by the predominantly Shia National Harmony Society (or National Accord Association), al-Wefaq, the largest opposition group.

In 2006 and 2010 al-Wefaq decided to participate and in 2010 won 18 of the 40 seats. In 2011 18 Wefaq legislators resigned from the Assembly in protest over the government’s heavy-handed response to largely peaceful pro-democracy demonstrations.

Al-Wefaq boycotted the by-elections held in September 2011 and the vacated seats were filled with pro-government candidates.

In January 2012, following a year of protests, the King announced constitutional amendments giving the National Assembly some modestly greater powers of scrutiny over the government, including the right to approve cabinets and to interpelate and remove cabinet ministers (but not the Prime Minister). These powers fell far short of the opposition’s demands.

The Constitution provides universal suffrage to all Bahraini citizens of at least 20 years; in 2011 the cabinet passed a draft resolution lowering the age to eighteen.

Al-Wefaq, Bahrain’s Shia-led opposition group, boycotted the November 2014 elections to protest what it called an attempt to establish “absolute rule”. As a result, the Sunnis won 27 seats, against 13 seats for the Shias.

The Judicial

Bahrain’s judicial system is based on both Islamic law (Sharia) and practice and on a Common Law model introduced by Britain prior to independence. Sharia law governs personal status issues (family law and probate). The Sharia courts handle matters of personal status for all Muslims, both Bahraini and non-national. The Sharia courts include separate Sunni and Shia courts.

The Civil Law Court handles all criminal and civil cases, as well as those personal status cases involving non-Muslims. Bahrain has a three-tiered court structure consisting of the High Civil Court, the Higher Court of Appeal, and the Supreme Court of Appeal (the Court of Cassation). A Higher Judicial Council, established in 2000 and chaired by the King, oversees the court system. All judges are appointed.

In 1975 the Emir also established a State Security Court to deal with matters of internal and external security. This court was abolished in 2001. In March 2011, however, the King declared a state of emergency and established a military court, the National Safety Court to try opposition members, presided over by a military judge and two civilian judges, all appointed by the Bahrain Defence Force.

A large number of dissidents involved in the 2011 uprising were imprisoned without trial or following trials internationally condemned for their lack of due process, lack of transparency and the use of torture and mistreatment during interrogation.

Many of these charges were detailed in a report issued at the end of October 2011 by the Bahrain Independent Commission of Inquiry’s Investigation (or Bassiouni Commission; see also Human Rights Watch’s report No Justice in Bahrain).

Corruption and Bureaucracy

While palace politics in Bahrain remain obscure, a powerful faction strongly opposed to all forms of political liberalization has emerged. These hard-line sheikhs are led by Sheikh Khalifa bin Salman Al Khalifa, the longest-serving Prime Minister in the Arab world.

One reason for their intransigence is that a parliament with real power might expose their (i.e. the family’s) corruption. Ever since the installation of the National Assembly (al-Majlis al-Watani) at the end of 2002, official corruption has been one of the most vehemently debated issues. Although ministers have appeared in parliament for questioning by deputies on alleged corruption, no government official has yet been brought to court.

Like all ruling families in the Gulf, the Al Khalifa rule mainly through the bureaucracy. Senior posts are distributed among the more powerful and/or loyal members of the family, and minor posts are given to members of a limited group of associated non-royal families. As a rule, these senior officials use their position to generate power and income. Government departments are ruled as personal fiefdoms by the ministers, enabling them to extract great wealth from their positions.

The name of Prime Minister and private businessman Sheikh Khalifa bin Salman Al Khalifa – who is known to appoint business associates to the National Assembly and is said to have amassed immeasurable wealth during his long tenure – has become a byword for government corruption and abuse of power.

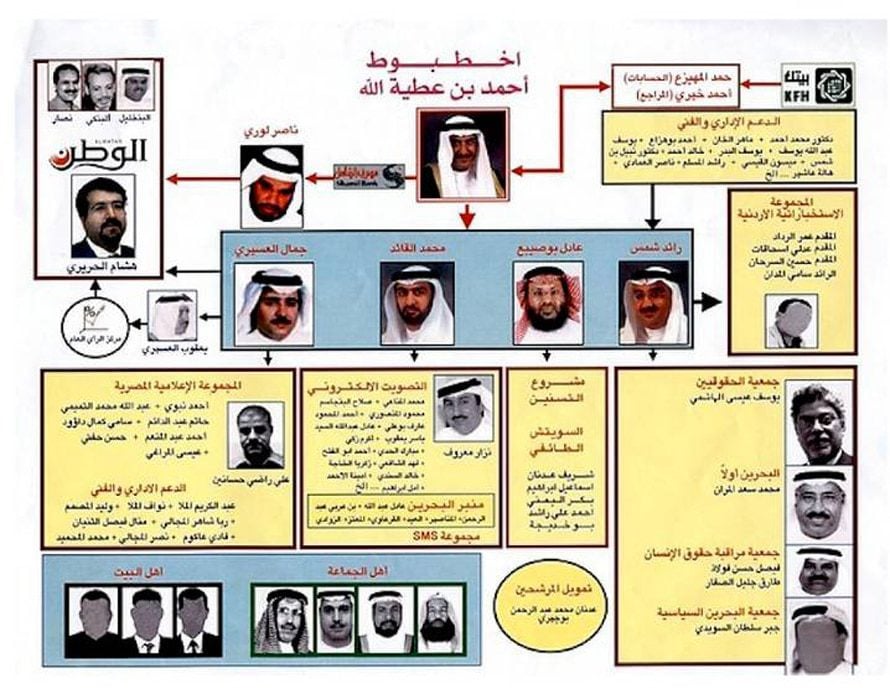

Bandargate

In September 2006, Salah al-Bandar Ibrahim, a British consultant to the government, was deported from Bahrain after leaking a secret report on manipulation of the upcoming elections through the incitement of sectarian hatred, naturalization of Sunni foreigners, and conversion of local Shiites. According to the report, the activities were financed mainly by Sheikh Ahmed Al Khalifa, founder of the Higher Committee for Elections. On the payroll were, among others, a Jordanian intelligence cell, a Sunni Islamist parliamentarian, and several local NGOs.

Accountability

For Bahraini officials, allowing politicians to speak their minds on corruption is more likely to result in punishment than in corruption charges. In November 2008 Ibrahim Sharif of the National Democratic Action Society accused the Prime Minister and his cabinet, in the local TV program al-Mizan (The Balance), of lying and misleading the public with regard to misappropriations of public funds. As a direct result, the Minister of Information was sacked.

Local Government

Bahrain’s government is highly centralized. The country has five governates (the capital, Muharraq, Northern, Central, and Southern), each administered by an appointed governor (in 2002 these governates replaced the previous division into twelve municipalities).

Each governate has a Municipal Council with ten elected members and an appointed chair. The councils are responsible for local services such as health and safety standards, public sanitation, and transportation. Elections for local Municipal Councils were held in 2002, 2006, 2010 and 2014.

Political Societies

Political parties are illegal in Bahrain; however a dozen or so registered political societies exist legally under a 2005 law and act effectively as political parties, fielding candidates and engaging in electoral activity.

In the 2010 elections the largest number of seats went to al-Wefaq, a Shia grouping (eighteen seats), al-Asala, a Salafi Sunni group (three seats) and al-Menbar, a Sunni Muslim Brotherhood society (two seats).

Two important unregistered groups who reject the political system as illegitimate are al-Wafa and the Haq Movement, formed by people who left al-Wefaq. While al-Wefaq is the largest and most important party, its support waned over the course of the demonstrations in 2011.

Somewhere between hardliners who dominate the government and the opposition are newer smaller but still important groups such as the political society the National Gathering of unity that support more gradual reforms.

Defence Force

Introduction

General instability in the Middle East, notably the civil wars in Iraq, Libya, Syria and Yemen, has helped Bahrain justify military procurement programmes, expansion and modernization.

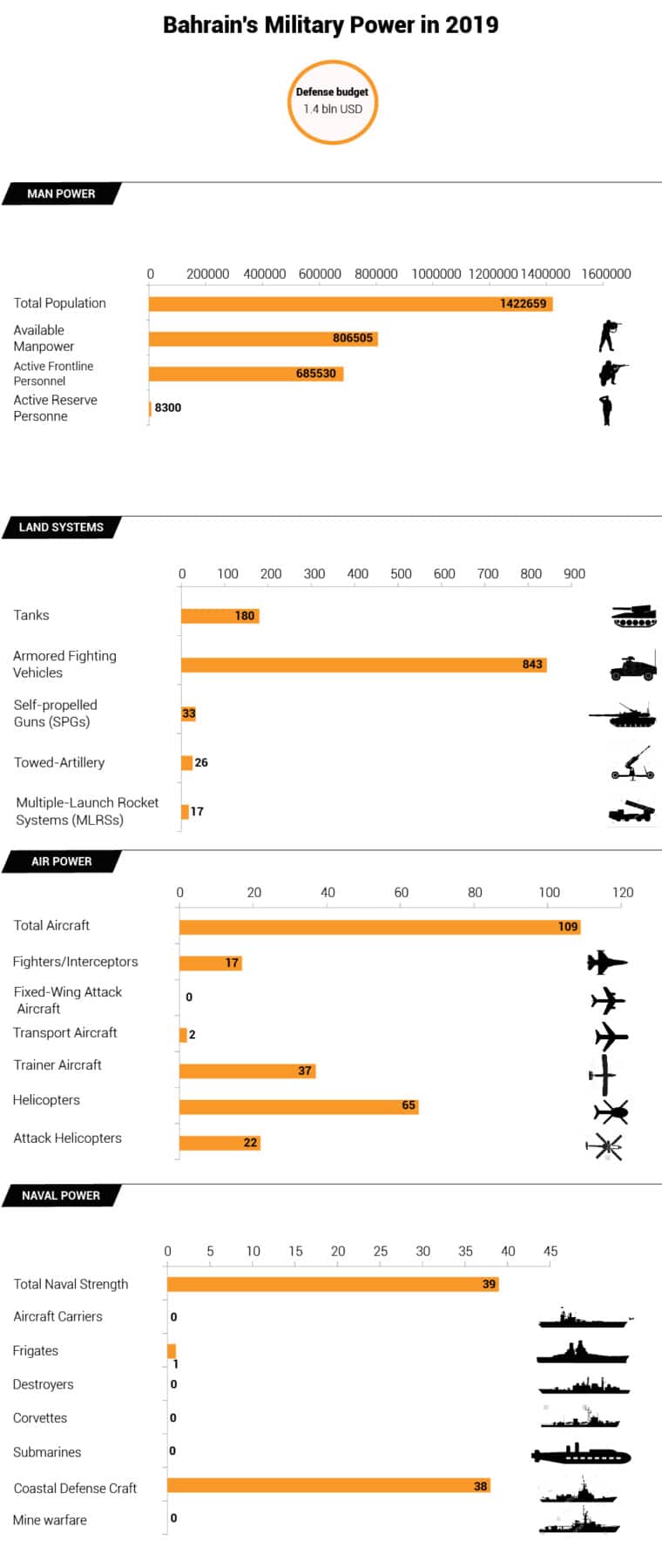

In 2019, Bahrain ranked 98 out of 137 countries included in the annual GFP review. 9That year, the number of people who reached military age was estimated at 17,255 personnel, while military expenditure was estimated at $730 million. In 2018, military expenditure accounted for 3.6 per cent of GDP, compared with 4.4 per cent in 2017 and 4.7 per cent in 2016y, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

| Index | Number | Rank out of 137 |

| Total military personnel | 8,200 | - |

| Active personnel | 8,200 | - |

| Reserve personnel | 0 | - |

| Total aircraft strength | 107 | 69 |

| Fighter aircraft | 17 | 54 |

| Attack aircraft | 17 | 59 |

| Transport aircraft | 2 | 52 |

| Total helicopter strength | 63 | 52 |

| Flight trainers | 37 | 52 |

| Combat tanks | 180 | 65 |

| Armoured fighting vehicles | 850 | 58 |

| Rocket projectors | 17 | 59 |

| Total naval assets | 39 | - |

| Frigates | 1 | - |

Bahrain’s military strength in 2019. Source: GFP review.

Key Facts

- Defence budget (2007): USD 550 million

- Active military personnel, professional: some 8,000

- Army: 6,000

- Navy: 700

- Air Force: 1500

- Paramilitary: 11,000

- MBT: 180 American M-60A3

- APC + AIFV: 200+ American M-113, French Panhard M3and (ex-Dutch) YPR-765

- Surface Combatants: one (ex-American) frigate, ten fast attack craft

- Combat Aircraft: 33 F-16 C/D

Defence Force

The Bahrain Defence Force, the principal military organization of this Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) member, was founded in 1968 by royal decree and is highly professional and well-resourced for its size.

The navy and air force can punch above their weight, thanks to the frigate Oliver Hazard and around 25 Perry and F-16 C/D jet fighters.

US Navy Fifth Fleet

The relatively small-staffed American Fifth Fleet is headquartered in the capital Manama. The units they command, however, are anything but modest, with the semi-permanent presence of a carrier battle group and expeditionary units of the Marine Corps.

The area of responsibility of the Fifth Fleet includes the Gulf, the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean in between. Also US Central Command (CENTCOM) heavily makes use of Isa Air Base on the south of the 655 square kilometre island.

Latest Articles

Below are the latest articles by acclaimed journalists and academics concerning the topic ‘Politics’ and ‘Bahrain’. These articles are posted in this country file or elsewhere on our website: