Introduction

Officially, Jordan is a constitutional monarchy that practices democracy, is governed by the rule of law, and respects human rights and media and academic freedoms. The reality is very different. The Constitution offers great powers to the King. He appoints the Prime Minister, the members of the upper house of Parliament, and judges, and he approves and promulgates laws. He convenes, and may suspend or dissolve, Parliament, and he orders, and may postpone, general elections. He commands the armed forces, declares war, and concludes peace. Article 30 of the Constitution stipulates: ‘The king is the head of state and is immune from any liability and responsibility.’

The Constitution’s numerous high-sounding safeguards of personal and other liberties all take second place to ‘the law’.

But laws are proposed by governments appointed by the King and are debated by a Parliament whose upper house is royally appointed and whose lower house has a built-in majority of regime loyalists who owe their parliamentary seats, in large measure, to electoral engineering on a grand scale. Parliament and political parties, key attributes of any democracy, play only marginal roles in national life. The media are free only within the constraints of overlapping and vaguely-worded laws that ban all criticism of the King and forbid anything that might upset national unity or foreign relations. The nominally independent judicial system is subject to interference by the authorities, albeit occasional and usually subtle.

Jordan is not, however, Saddam Hussein’s Iraq or Hafiz al-Assad’s Syria. The security services are feared and effective but do not function routinely as instruments of terror. Dissidents can be detained and tortured, but they do not ‘disappear’. There is no blanket surveillance of the populace. Within prescribed limits, the media are lively and diverse and, within limits, parliamentary debates can be vigorous. While the laws with which it deals are framed by and for the establishment, the judicial system is largely fair. While the universities, like all national institutions, must toe the official line, they and their academic staff enjoy much independence. Most Jordanians, most of the time, enjoy a freedom that has set them apart from most peoples of a region largely ruled by autocrats disdainful of democracy and human rights.

The Legislative

Parliament, also known as the National Assembly, comprises an upper house (the Senate, or House of Notables) appointed by the King and an elected lower house (House of Representatives, or Chamber of Deputies). Prime Ministers must submit their cabinets to Parliament for a vote of confidence.

At any stage, the lower house can submit a motion of no confidence in a government or an individual minister. If passed by a majority, the cabinet or minister must resign. Members of the lower house are entitled to question the government on any public issue. Governments submit legislative proposals to the lower house for debate and approval by majority vote.

Bills are then passed to the senate for debate and approval, again by majority vote. After approval there, a bill goes to the King, who may either grant his assent by royal decree or return the bill to the lower house, with an explanation of his objections. The deputies then review and vote on an amended version. Bills rejected by the senate are returned to the lower house for amendment.

If the two houses cannot agree on a bill, the matter is settled by a two-thirds-majority vote at a joint session of the two. The monarch’s veto of legislation can be overruled by a two-thirds-majority vote at a joint session of the two houses. If the government amends or enacts a law when Parliament is not sitting, the law must be submitted for approval when Parliament next convenes.

The Constitution stipulates that the number of senators cannot be more than half the number of deputies. The original Jordanian Parliament, formed in 1947 a year after the kingdom’s nominal independence from the United Kingdom, comprised a twenty-seat elected lower house and a ten-seat appointed upper house. The numbers of seats has since been increased, most recently in 2012, from 120 to 150 for the lower house.

Continuing a longstanding practice, nine seats of the 150 seats are reserved for Christians, nine for Bedouins, and three for either Circassians or Chechens. In February 2003 King Abdullah decreed that six further seats should be reserved for women, and this women’s quota was raised to fifteen in 2012. Since 1973, when women gained the vote, suffrage has been universal.

Senators – comprising notables such as former prime ministers and ministers, tribal leaders, retired senior military officers, former diplomats, and judges – are appointed for four-year terms, with half retiring every two years. Deputies are elected for four-year terms. Lower- and upper-house sessions are held simultaneously, and Parliament sits for only four months annually, an important reason for its limited role in the country’s political life.

Voting in parliamentary elections takes place in 45 constituencies, or ‘electoral zones’, each represented by several parliamentary seats, but voters may choose only one candidate. Each constituency is sub-divided into the same number of non-geographic, or ‘virtual’, sub-districts as it has seats. Candidates stand in one of the sub-districts, but voters can choose to vote for any candidate standing in the wider zone. The candidate who wins the most votes in his or her sub-district is elected.

Despite approval of a new electoral law in July 2012, the electoral system is still designed to favour regime loyalists. Furthermore, it did not lead to a greater role of the opposition or political parties. The elections of 23 January 2013 produced a pro-government National Assembly.

Following electoral reforms in 2015, the number of seats in the House of Representatives was reduced from 150 to 130. The new law also allowed multiple votes for open proportional lists, replacing the old single-vote system. In the subsequent legislative elections on 20 September 2016, the opposition National Coalition for Reform, an alliance of Islamist, tribal, nationalist and Christian figures, won only 15 seats. The majority of elected MPs were either individuals with tribal affiliations or businessmen, as had been the case during the past two decades.

Elections and Suspensions of Parliament

The marginalization of Parliament in Jordanian politics is emphasized by the numerous occasions on which the monarch has suspended Parliament and postponed elections. In 1970, for example, citing the continued Israeli occupation of the West Bank, King Husayn postponed elections scheduled for that year and decreed that serving deputies, elected in 1967, would remain in office.

In 1974 he dissolved the House of Representatives, subsequently announcing that new elections would be held in March 1976. In February 1976, however, he recalled the old chamber, which convened only long enough to approve the indefinite suspension of new elections before adjourning.

Two years later the King appointed a 60-member National Consultative Council (NCC) to act as an interim quasi-parliament. In January 1984 he dismissed the NCC and reconvened the long-adjourned National Assembly. Although appointing new members to the senate, he recalled the same lower house that had been elected in 1967 and had last met, briefly, in 1976. In 1988 the King dissolved the House of Representatives and decreed an indefinite postponement of elections. Following riots in April 1989, however, elections were scheduled for November of that year.

The 1989 elections, the first for more than 22 years and with a turnout of 70 percent, were widely acknowledged to be free and fair. Almost half the seats were won by oppositionists – that is, candidates not from the traditional East Bank establishment. Conservative Islamists emerged as the biggest single parliamentary bloc, with the Ikhwan al-Muslimun, or Muslim Brotherhood, winning 22 of the 80 seats and independent Islamists a further 10-14 seats, depending on the definition used.

Leftists, pan-Arabists, liberals, and reformers won between ten and 15 seats. Loyalist traditionalists – urban and rural notables, badu (Bedouin) sheikhs, and former senior officials – won 31 seats. The Parliament, which sat from 1989 to 1993, was livelier by far than its rubber-stamp predecessors, hotly debating matters that had previously been taboo.

Although the 1989-1993 Parliament never fundamentally challenged the status quo, the regime took no chances. In 1993, shortly before the elections scheduled for November that year and after the previous Parliament had been dissolved, the electoral law was amended by royal decree to prevent the opposition from building on its success.

Each voter in Jordan’s multi-candidate constituencies had previously had one vote per candidate and could cast as many of those votes as they desired (although they could not vote more than once for the same candidate).

This meant that, in addition to voting on the basis of tribal or local loyalties, they could also vote for ‘ideological’ candidates such as the Islamists. The new ‘one man, one vote’, system permitted only a single vote. Given most Jordanians’ strong allegiances to tribe and locality, the inevitable and intended result was to favour traditional, loyalist candidates.

That is not the only means by which the electoral system has been engineered to maintain the primacy of the traditional, East Bank elite. In 1989, following its disengagement from the West Bank, the Kingdom’s electoral districts were carefully redrawn in a way that profoundly favoured East Bankers at the expense of Jordanians of Palestinian origin. In particular, cities – where most Palestinians and most members of the middle classes, who are generally more interested than rural dwellers in ideological and foreign policy issues – are under-represented, and rural areas are over-represented.

Only 26 oppositionists won seats in the 1993 election. The 1997 results were even more flawed, because the Islamic Action Front (IAF, the party of the Muslim Brotherhood) and seven smaller parties boycotted the poll to protest the 1993 electoral-law amendment and the wider erosion of liberties since the start of the decade.

The election scheduled for November 2001 was postponed, first on the grounds that more time was needed for the drafting of a new electoral law and then because of the ‘difficult regional situation’. The election was eventually held on 17 June 2003 and, like earlier polls, was generally free and fair. Despite threats to boycott this poll too, the IAF participated but won only 17 seats. In the November 2007 poll the IAF won a mere six seats.

In November 2009 King Abdullah II dissolved Parliament – which had been widely criticized as ineffective – two years before the completion of its term. Following a delay to allow the drafting of a new electoral law, issued in May 2010 – which did nothing to redress the rural-urban representational imbalance and, if anything, exacerbated it – new elections were held in November 2010 but were boycotted by the IAF, to protest an electoral system it deemed unfair.

As expected, the elections led to a victory of pro-government candidates. Only one political party candidate was elected (due to the women quota) and around 12 percent of seats were occupied by Palestinian Jordanians. Since 1993, when the one-person one-vote system was introduced, voters had used their sole vote to support a relative or a member of their own tribe or clan, leading to a weakening of political parties.

This trend did not change with the elections of 23 January 2013, despite minor amendments of the electoral law introduced in July 2012. Jordan’s Independent Election Commission (IEC) reported a voter turnout of 56.5 percent (up from 52 percent in 2010). Turnout was far higher in the tribal areas.

Increasing the number of seats for national lists did not lead to strengthening of political parties; rather, lists were created based on personal influence instead of political programmes. Official results (Arabic only) indicate that fifteen women were elected and 27 candidates represented 22 national lists (which means that most lists have only one seat). With the previous electoral system mostly intact, loyalists of the regime again achieved victory.

The National Democratic Institute (NDI), which participated in an international observation mission, reported that the election process had significantly improved. Under the newly established IEC, the registration, voting and counting of votes had been improved when compared to earlier elections. Yet, the NDI noted that the electoral law remained problematic. unequal size of districts and an electoral system that amplifies tribal and familial relations limit the development of a truly national legislative body.

This challenges the King’s stated aim of encouraging full parliamentary government, according to the NDI. However, the fact that opposition forces are still constrained due to uneven representation and the weak position of political parties, emphasizes the regime’s interest in preserving the status quo rather than really delivering on earlier promises of change.

In the subsequent legislative elections on 20 September 2016, the opposition National Coalition for Reform, an alliance of Islamist, tribal, nationalist and Christian figures, won only 15 seats. The majority of elected MPs were either individuals with tribal affiliations or businessmen, as had been the case during the past two decades.

The Judicial

Jordan’s legal system is a combination of European and Sharia (Islamic law) traditions. During the 19th century, when the territory was part of a reforming Ottoman empire, civil and criminal codes based on French law were introduced but were modified to accommodate Islamic precepts. English common law was introduced into British-mandated Palestine, but in Transjordan, where Britain did not rule directly, the older legal system persisted, albeit with extensive amendments that strengthened its European aspects.

In 1956 Parliament adopted a new criminal code modelled on those of Syria and Lebanon, which were themselves derived from the French system. Reflecting this background, there is no jury system, and it is the judges who weigh evidence and pronounce verdicts, as well as ruling on matters of law.

The Constitution provides for three types of court: civil, religious, and ‘special’. Religious courts deal with personal status and family matters, including marriage, divorce inheritance, and alimony, while civil courts adjudicate routine criminal and civil cases. The religious courts include Sharia courts for Muslims and canon-law courts for Greek Orthodox, Roman Catholics, and Anglicans, although these Christian courts apply Sharia in inheritance matters in accordance with long-standing custom. A special court appointed by the Court of Cassation (see below) rules on disputes between different religious courts and between religious and civil courts.

Civil court system

Jordan’s civil (nizamiya) jurisdiction embraces a four-tiered hierarchy of courts. The 14 Magistrate (sulh) Courts hear lesser cases involving small claims and offences carrying small fines or a penalty of up to two years’ imprisonment. More serious cases are heard by the seven Courts of First Instance (of which Amman’s Higher Criminal Court is one), each with a panel of three judges for criminal matters and two judges for misdemeanours and civil matters.

The First Instance Courts also hear appeals from the Magistrate Courts. Appeal courts, comprising a panel of three judges, hear appeals from both the First Instance Courts and the religious courts. Contested Appeal Court decisions are heard by the five-judge Court of Cassation, which is Jordan’s supreme court. The civil-court system also includes the Higher Court of Justice, which hears cases against governmental agencies, and specialized courts for cases involving taxation and customs.

Special courts

Parallel to the civil-court system is a series of special courts. The State Security Court, consisting of a panel of two military judges and one civilian judge, deals with cases involving sedition, armed insurrection, offences against the royal family, financial crimes affecting the national economy, and trafficking in weapons and drugs (see below). Military courts try cases involving all offences by armed-forces personnel. A High Tribunal may try ministers and may interpret the Constitution at the request of the cabinet or either house of parliament.

Its interpretations are binding. The Tribunal comprises the speaker of the senate, three senate members who are elected by the senate, and five senior judges. At the behest of the Prime Minister, a Special Tribunal, whose decisions are also binding, may interpret the provisions of any law that the courts have not yet interpreted. It comprises the presidents of the highest civil courts, two other senior judges, a senior administrative official appointed by the cabinet, and a senior official appointed by the concerned minister. Neither the High Tribunal nor the Special Tribunal are standing bodies, both being convened ad hoc – in practice, very rarely.

Degree of independence

The independence of the judiciary and the courts is enshrined in the Constitution, and in the great majority of routine cases the judiciary and courts are independent, and citizens can expect fair trials. The process can sometimes be very lengthy, with frequent adjournments, reflecting the great demand in relation to resources and the persistence of outdated work methods, often including the recording of proceedings and the drafting of judgements in longhand.

In cases involving ‘national security’ or threatening the financial or other interests of powerful officials, however, the picture is less positive, although there is little of the systematic financial corruption and political interference that characterizes the legal systems in other regional states, such as Syria. Scope for abuse is offered by the system’s structure.

As a whole, it is funded and administered by the Ministry of Justice. Judges are appointed, assigned to jurisdictions and cases, and evaluated by a theoretically independent High Judicial Council of twelve senior judges, who are, in turn, appointed by the King. But the Council is overseen day to day by the ministry, which has been accused of undermining its independence. A June 2001 law introduced measures to distance the ministry from the council, but allegations of interference persist.

The State Security Court has attracted much criticism from Amnesty International and other human-rights organizations. The court, which is the successor to the military tribunals of the martial-law period and to which cases are brought by a special state-security prosecutor, may have two military judges and one civilian judge, although it has usually been staffed by military judges. Cases and trials are normally open to the public, although some are open only to the press.

Decisions may be appealed to the Court of Cassation, which can review matters both of fact and of law, and such appeals are mandatory in cases in which the death sentence has been imposed. Although the court’s procedures are based on those of the criminal courts, there are fewer safeguards for defendants.

Legal System

In the period when the Emirate of Transjordan was created, most of the laws and regulations were based on English law. Civil law, however, was based on the Ottoman Mecelle, which was adapted from Sharia (Islamic law). This continued until 1978, when the Mecelle was replaced by Jordanian civil law, some of whose elements are derived from Ottoman law and others from Egyptian civil law. Egyptian civil law was, in turn, adapted from the French and other civil codes and covers all civil contracts and transactions, such as rental contracts, contracts of sale and purchase, bail, and all other civil transactions between people.

Jordan’s personal-status law is based on Sharia and covers family matters, including marriage, divorce, inheritance, wills, custody, and legal guardianship of children. Jordan’s Christian minority has its own courts that have jurisdiction over marriage, divorce, custody, and legal guardianship among Christians, but matters of inheritance and wills are based on Sharia.

The country’s penal code includes penalties for crimes including adultery, theft, sexual assault, activities endangering national security, embezzlement, and any crimes that harm person or property. Basic human rights and public freedoms are also mentioned in the legal system and in the Jordanian Constitution.

Political Parties

Jordan has some 30 registered political parties, but all save one are small, and most are ideologically difficult to differentiate. Most are simply non-ideological gatherings around individuals, many of whom represent tribal groups.

The leftist and nationalist parties retain small followings but suffer from having been banned and repressed from 1957 until 1992. Perhaps more profoundly, their ideologies have been discredited, the Communists by the collapse of the Soviet Union and the nationalists by the Arab defeat in the 1967 war with Israel and by the cruelty and incompetence of nationalist regimes in Egypt, Syria, and Iraq.

The only organized, effective party with a clear ideology and a national following is the Islamic Action Front (IAF). Created in 1992, when parties were legalized, the Front, which has 23 branches across the country, is the political wing of the Jordanian branch of the conservative Muslim Brotherhood, although its members also include independent Islamists.

Cabinet Shuffles and New Opposition

Cabinet Shuffles

In Jordanian politics a pattern has emerged in which King Abdullah frequently replaces his Prime Ministers. Between his accession to the throne in 1999 and 2012 Jordan has had no less than eight PM’s. Continuously vacillating, the King has shifted trust from one camp to the other, appointing Prime Ministers with quite different political views, wavering between conservatives and the opposition – all in a bid to buy time. Since the short-lived governments were unresponsive to any substantial reforms as demanded by the opposition, the political crisis in the country has only deepened.

In the midst of calls for political and economic reforms and an end to widespread corruption, Jordan, in 2011-2013, witnessed a series of cabinet reshuffles. In October 2011, the King replaced Prime Minister Marouf al-Bakhit with Awn al-Khasawneh, a former judge at the International Court of Justice in The Hague. Al-Khasawneh took office as a liberal reformist, raising hopes for reform. Al-Khasawneh denounced corruption and announced the end of the intelligence services’ interference in public affairs. He also began a dialogue with the opposition. However, it soon became clear that he was unable to deliver. The new election law that al-Khasawneh presented, did not allow for a strong and representative legislature and was for that reason turned down by the opposition.

He also wanted to postpone the general elections for a year (until 2013), in order to have time to negotiate a more equitable electoral system, enticing the political wing of the Muslim Brotherhood (Islamic Action Front or IAF) to join in. In April 2012 al-Khasawneh resigned, reportedly in protest over the King’s refusal to implement meaningful political reforms – which would weaken his absolute powers.

Al-Khasawneh was replaced by a conservative, former palace official, Fayez al-Tarawneh. The opposition was disappointed, as the new government was dominated by elderly regime loyalists, and included only one woman. Implementation of reforms which would meet popular demands was not to be expected. Nevertheless, the King promised that elections would take place before the end of 2012 and that he would choose a new government with parliamentary support.

In May, Jordanians protested against government plans to raise commodity prices and taxes. After Parliament passed a new electoral law in June, and the King approved an amended version in July, hundreds of protesters rallied around the country against the elections. The King ignored a memorandum by 500 national, partisan and unionist figures, that demanded that the election law be aborted. In September, he endorsed the controversial new media law. In the face of wide public opposition, he dissolved the Parliament on 4 October, after which Prime Minister al-Tarawneh resigned.

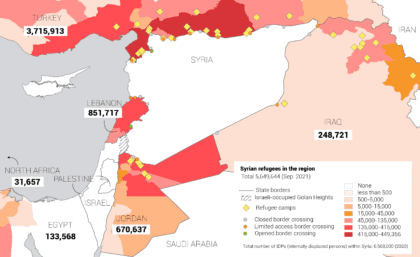

The King appointed Abdullah al-Nsour as caretaker Prime Minister until the elections of January 2013. Al-Nsour, who was tasked with introducing austerity measures to guarantee an IMF loan to Jordan, faced vast protests after he announced in November 2012 the removal of subsidies and price hikes of commodities like cooking gas and electricity. Al-Nsour refused to cancel the subsidy cuts; the IMF agreement constrained his ability to compromise on the issue. Jordan is increasingly struggling to maintain a system in which it traditionally bought the support of an important part of the population (East Bankers). Moreover, the budget is under increasing pressure as a result of the fast influx of Syrian refugees, which is placing a heavy burden on the Jordanian economy.

After the elections of January 23, 2013, which produced a similar parliament as before, more signs of continuity appeared. The new Parliament elected Saad Hayel Srour as speaker. He had served in the post several times before. Former Prime Minister al-Tarawneh, a conservative veteran, was appointed chief of the Royal Hashemite Court. March 2013, Abdullah al-Nsour was again appointed as Prime Minister.

New opposition

Most significant – and an alarming development from the monarchy’s perspective – is that traditional supporters of the throne – tribal East Bank Jordanians – are now also voicing opposition. These Jordanians – as distinct from Jordanians with a Palestinian refugee background – work in the government administration, army and dominate the secret services. As such they have benefitted from public sector employment and subsidies. However, due to cuts in public spending, privatization and the collapse of the agricultural sector, they have lost much of their privileged position. Focusing on material demands and railing against the corruption, many have begun to criticize the King openly and joined the protests of the Muslim Brotherhood (Islamic Action Front or IAF).

Consolidating support

In an effort to consolidate (East Banker) support through employment and subsidies, the King has sought financial support from foreign backers. Although the United States has remained a traditional ally, Jordan has found more robust alternatives, with both Saudi Arabia and the Gulf Cooperation Council offering Jordan financial support. In 2011 Saudi Arabia’s funding exceeded US aid by over USD 1 billion. In addition, Saudi Arabia has invited Jordan (and Morocco) to apply for GCC membership.

East Bank Jordanians still enjoy disproportionate representation in Parliament and government due to the election system, which favours the rural areas over the cities. Yet many fear that the majority of Palestinian Jordanians – strongly represented in the economy – will gradually take over. Over the years the King and his Palestinian wife Queen Rania have favoured the position of middle class Palestinian Jordanians, whom they increasingly rely on for support. Other Palestinian Jordanians have joined the oppositional IAF, which now has a large Palestinian base.

In the course of 2012 outside pressure to implement reforms has notably diminished due to developments in neighbouring Syria. Shocked by the violence there, a growing number of Jordanians are now emphasizing political stability over democratic reforms.

The Military

Introduction

Geographically, Jordan is surrounded by volatility in neighbouring Israel, Syria, Iraq, Saudi Arabia and Egypt. It is unsurprising, then, that its armed forces have often been thought of as among the most capable in the region.

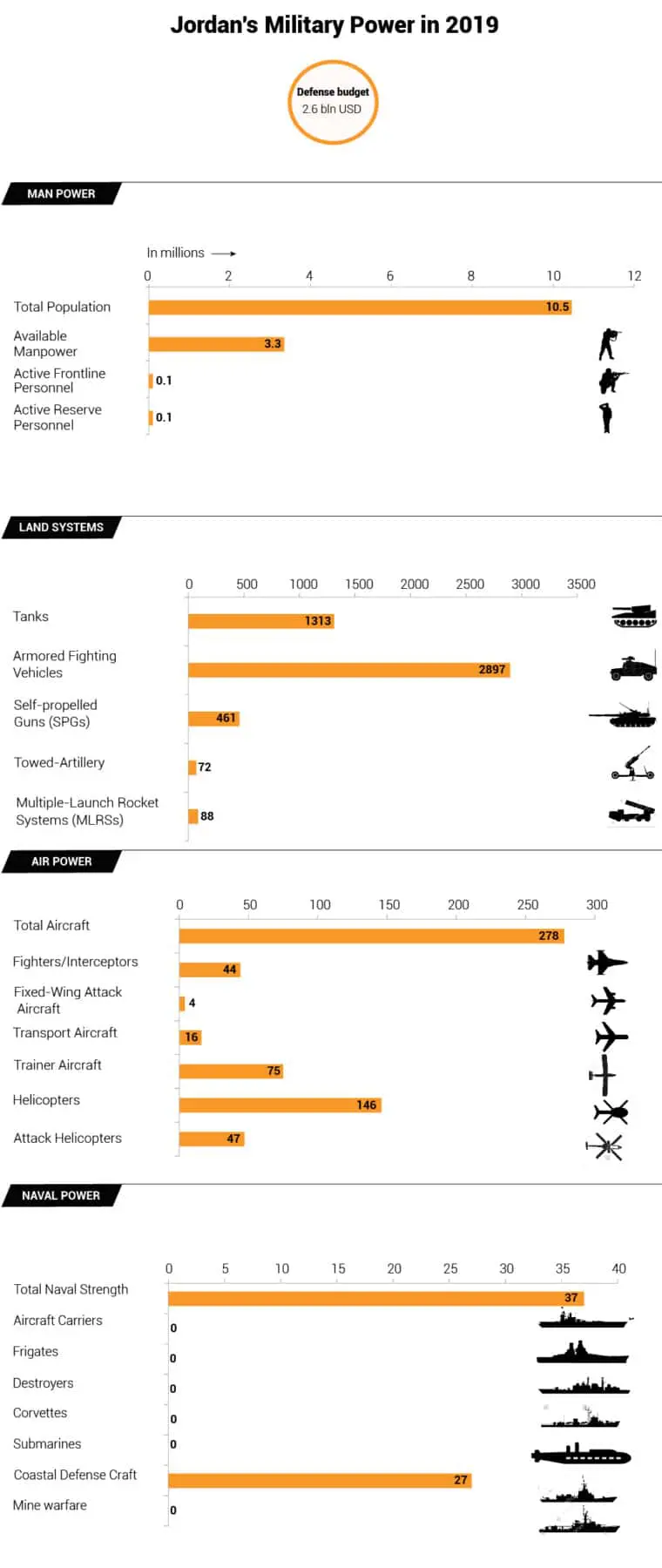

In 2019, Jordan ranked 76 out of 137 countries included in the annual GFP review. That year, the number of people who reached military age was estimated at 143,238 personnel, while military expenditure was estimated at $1.5 billion. In 2018, military expenditure accounted for 4.7 per cent of GDP, compared with 4.8 per cent in 2017 and 4.6 per cent in 2016, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

Due to the lack of and precarious nature of military information, it is not always possible to obtain reliable data about the armed forces of the various countries in the Middle East. To a certain extent this also applies to Jordan’s Armed Forces.

Defence budget (2009) USD 2.4 billion

Active military personnel

(all volunteer, no conscription)

- Army 88,000

- Navy 500

- Air Force 12,000

MBT 1,100 British Challenger 1, American M60

APC + AIFV 1,600 American, British, Russian, South African mix

Surface Combatants a dozen light patrol craft

Combat Aircraft 100 F-16, F-5 Tiger-II, Mirage

Attack helicopters some 25 Bell AH-1 Cobra, order of two dozen AH-6 Little Bird likely

Due to it’s critical position sandwiched between Iraq, Saudi Arabia and Israel, Jordan maintains a strong defensive army. The army has set up three ‘control zones’: the North Army Command, the Central Army Command and the South Army Command. Each control zone is under the command of a general, who together are accountable to the King, as supreme military commander. The present-day Jordanian Armed Forces are equipped with mainly Western (American and British) supplied weapons and weaponry.

Royal Jordanian Air Force

The Royal Jordanian Air Force uses F-16 fighter planes, with up to 55 in Royal Jordanian Air Force (RJAF) service. In 1997, the RJAF obtained their first sixteen F-16s. Some were ex-USAF aircraft equipped with AMRAAM radar-guided air-to-air-missiles and upgraded by Turkish Aerospace Industries, other F-16s were from surplus stocks from the Netherlands and Belgium.

Jordan also still uses a handful of French Mirage F1CJ/EJ fighter planes and has obtained up to six Spanish Air Force Mirages, which the Spanish are believed to have bought off Qatar. The F-5 is gradually being replaced. Reports in the press have suggested that Jordan wants to own up to 80 F-16s in total, but the country is more likely to retain the Mirage F1 for some years to come, rather than choose for one single type of fighter plane.

There is no major requirement for Jordan to replace the transport fleet of six C-130H Hercules transport planes, but the government has obtained two smaller CASA/EADS C-295 transport planes from Spain and ordered two IL-76MF transport planes from Russia.

Local air defence comes under RJAF command and consists of five Patriot batteries, five HAWK batteries, six Skyguard batteries and the SA-8 an SA-9 surface-to-air-missiles. The RJAF also owns ZSU-23-4 Shilka self-propelled anti-aircraft artillery.

The range of products emanating from KADBB varies from sensors to vehicles, firearms, missiles, observation planes and UAVs. In December 2011 it came to light that the KADDB will start licence-producing the Russian RPG-32, shoulder-fired anti-tank-weapon.

| Index | Number | Rank out of 137 |

| Total military personnel | 200,000 | - |

| Active personnel | 100,000 | - |

| Reserve personnel | 100,000 | - |

| Total aircraft strength | 290 | 36 |

| Fighter aircraft | 44 | 41 |

| Attack aircraft | 50 | 46 |

| Transport aircraft | 18 | 38 |

| Total helicopter strength | 149 | 30 |

| Flight trainers | 74 | 37 |

| Combat tanks | 1,313 | 19 |

| Armoured fighting vehicles | 2,847 | 24 |

| Rocket projectors | 88 | 37 |

| Total naval assets | 37 | - |

Jordan’s military strength in 2019. Source: GFP review.

Aid operations

The Jordanian Armed Forces have contributed and still contribute to UN peacekeeping missions worldwide, most notably in Africa, Afghanistan, the former Soviet Union, Haiti and East Timor. The RJAF plays a critical role in aid and relief operations. The acquisition of two long-haul Ilyushin IL-76 transport planes in 2005 has helped the Jordanian government to support Jordanian blue helmets on missions far away. In 2006, RJAF aircraft flew several humanitarian aid-missions with relief goods to Lebanon and brought a field hospital to the Lebanese capital. Royal Jordanian Army Engineers also carried out numerous operations to destroy unexploded ordnance dropped by Israeli forces.

Army equipment

The Jordanian Army is equipped with a mix of British and American tanks, including the British Challenger 1 and American M-60A1/A3. The older Chieftain and M-48A5 series remain in limited service, but both models may be phased out as the Challenger and M-60A1/A3 are to undergo further upgrades. Current projects carried out by KADDB (King Abdullah Design and Development Bureau) include upgrades such as the integration of the Phoenix digital fire and control system and a revised turret for the M-60A1/A3, featuring explosive reactive armour. The Jordanian government wishes to export this revised turret. It has been offered as an upgrade to existing M-60 tank users such as Egypt or Saudi Arabia.

The M113 remains the standard Armoured Personnel Carrier for Jordan although they are slowly being phased out and replaced by locally-produced vehicles, including the Temsah (Crocodile). Two dozen Cobra attack-helicopters provide extra firepower for the army. Not to mention, the Cobras are equipped with TOW anti-tank missiles.

In January 2012 the Army took delivery of the first of twelve High Mobility Artillery Rocket Systems (HIMARS), which greatly increases the precision fire-power of this service.

Personal equipment for soldiers includes the US-supplied M-16 automatic weapon.

In February 2016, former US President Barack Obama signed a law allowing military support to Jordan to increase to $450 million that year.

Additionally, in March 2016, the US delivered eight Black Hawk helicopters to Jordan to help its regional ally defend itself against the threat of the Islamic State. Another eight Black Hawks arrived a year later, as part of a military deal worth $200 million.

In January 2016, Jordan also signed an agreement with Kazakhstan to purchase 50 Arlan armoured personnel carriers.

Defence industry

The Jordanian Armed Forces are becoming, because of the growing domestic defence industry, increasingly less dependent on foreign weapon technology. Moreover, the Jordanian defence industry is becoming an expert in the niche market of special forces equipment. The annual SOFEX exhibition held in the capital Amman is proof of this. Before King Abdullah took the throne, he was a Jordanian Special Forces officer. One of the more visible industrial entities is the King Abdullah II Design and Development Bureau (KADDB), established in 1999.

Latest Articles

Below are the latest articles by acclaimed journalists and academics concerning the topic ‘Politics’ and ‘Jordan’. These articles are posted in this country file or elsewhere on our website: