Introduction

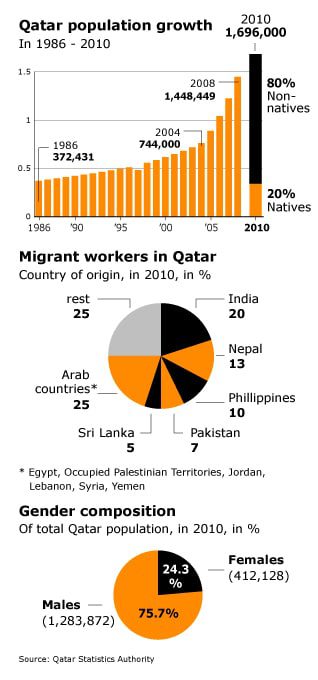

The population of the State of Qatar as of April 2024 was 3.098 million, according to the Planning and Statistics Authority, distributed to 2.190 million males and 908.115 thousand females.

According to the results of the official population census in 2015, the total population of the State of Qatar reached about 2.642 million, with an average annual growth rate of 6.9% during the period between the 2010 census and the 2015 census. The percentage of males was 75.6% compared to 24.4% for females. The number of families reached 201,432 families in 2015, and the average size of the family was 4.7 members.

Despite the constantly increasing number of population in Qatar, the population growth rate is characterized by clear fluctuation. This rate reached 13.1% in 2009, then fell sharply to 4.8% in 2010, and then to 1.4% in 2011.

In the period between (2000-2022), the average annual growth rate was 6.5%; While it reached 10.6% between 2013-2014, it decreased to less than 1% between 2016-2017 AD, and to 0.3 % in 2022, as the population reached 2.7 million people in 2017, an increase of nearly 59 thousand people over what it was in 2017 AD. A growth of 2.26%, then 2.07% in 2018, then 1.8% in 2019, and finally 0.3% in 2022.

The imbalance in the demographics in terms of the decline in the number of Qatari citizens indicates an imbalance between the average natural growth rate for Qataris (2.7%) and the average abnormal growth rate for expatriates (7.4%), during those years.

Sexual dysfunction in general, in the demographics, the most recent in 2020 AD (72.1% for males, 27.9% for females), is because most of the expatriates are young men and men who come to Qatar to work without their families.

United Nations data estimated that the number of “non-Qatari” expatriates in the population mix in mid-2017 was estimated at 1.721 million, and by 65.5% of the total population at that date. The percentage of males in the number of arrivals was 83.9%, compared to 16.1% of females, with a gender ratio of 521 males for every 100 females.

In 2023, the demographic composition of the State of Qatar indicated in 2023, according to the Planning and Statistics Authority, that the Qatari population constitutes only about 11.3% of the total population of the country, as the state includes two demographic structures, one for the Qatari population and the other for the non-Qatari population.

Reports indicated that in 2017 the population of Qatar consisted of 87 different nationalities. Other reports indicated that there were approximately 2 million migrant workers in 2018. Perhaps this is what prompted sources to describe Qatar as “the state built by immigrants.”

The official language in Qatar is Arabic, but English is commonly used as a second language. According to 2010 estimates, Muslims constituted approximately 67.7% of the total population, followed by Christians by 13.8%, Hindus by 13.8%, and Buddhists by 3.1%, and the rest were other religious minorities who were not affiliated with any religion.

Age Groups

Besides describing it as masculine, the Qatari society can be described as a young society in terms of the age structure of the population in 2020 AD, where 12.84% of the population is under the age of fifteen, according to the estimates of the CIA World Factbook, during the year 2020 AD; And 11.78% between 15 and 24 years old, and 70.66% in the age group [25-54 years], 3.53% in the age group [55-54 years], and only 1.19% at 65 years and over.

According to the UNFPA Population Database, the total fertility rate of the Qatari population is low. As it reached 1.9 births per woman, with the average childbearing age increasing to 29.9 years, in 2018. The National Planning and Statistics Authority attributes this to the improvements in education and the increase in the number of working women.

On the other hand, there is an increase in the total fertility rate of the non-Qatari population, which totally affects the total population.

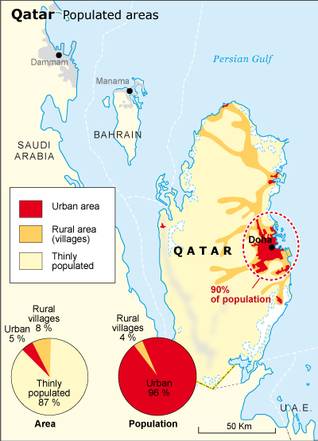

Areas of Habitation

Qatar is considered one of the countries with a high population density, reaching about 232 people / km2, in 2020 AD, with an urbanization rate of 99.2%, while the population density was about 209 people / km2, according to the last official population census in 2015.

According to the results of the 2015 census, the municipality of the capital, Doha, acquired 42% of the total population, followed by Al Rayyan with 25%, and Al Wakra with 12% and the rest of the population is distributed among the remaining five municipalities in varying proportions.

It is noteworthy here that the strict regulations to regulate family housing, prohibit migrant workers from living in certain places in the country, especially the capital, Doha. A decade ago, most migrant workers lived in and around the capital, but with numbers of immigrants in Qatar rising from 1.1 million in 2008 to 1.97 million in 2018, they have since been gathered in huge labor camps, often in remote locations., To make room for new developments in the city.

Some shopping malls, parks and public places are also off-limits to migrant workers, especially on weekends and holidays. This policy appears to be driven by concerns about mixing “bachelors” with women in a country where women have fewer than a quarter of the population.

Nationality and Residence

The Nationality Law of 1961 granted Qatari citizenship to anyone who was able to prove settlement in the country before 1930. In the following years, additional laws granted Qatari nationals some exclusive rights such as ownership of immovable property and commercial businesses. These last two measures were explicitly designed to guarantee native merchants a certain degree of prosperity. It was a successful attempt by the governing elite to neutralize resentment against the merchants’ earlier political marginalization, which had been a side-effect of the creation of an Al Thani-controlled centralized state bureaucracy, based on oil revenues.

To this very day, Qatari nationals retain the exclusive right to own immovable property (land or buildings) and are provided with free health care, electricity, water, and education. The Sunni nationals have historically determined privileged access to jobs in the public sector, Shia nationals are predominantly working in the private business sector.

In 2005, a new nationality law came into being, allowing for non-citizen residents who have resided in the country for twenty-five consecutive years to apply for citizenship. However, a maximum of just fifty residents are granted citizenship annually, and there is no such thing as a ‘right’ to citizenship, even if a non-citizen was born and raised in Qatar. By 2008, only a very small number of applicants had been accepted.

In 2018, a law was passed allowing children of Qatari women married to non-Qataris and their husbands to obtain permanent residency in the country. However, children and husbands of Qatari women are not permitted to acquire citizenship.

Under the new law, about 100 people per year can be granted permanent residency for the first time in Qatar. Permanent residents may travel to and from the country freely, obtain health and educational government services, invest in the economy, and own real estate.

Bedouins and Hadar

Many Qatari nationals – especially the older generations – pride themselves on their Arab Bedouin descent. Qatar’s tourist industry is trying to profit from this sentiment by promoting the country’s culture as being based upon an age-old, ‘genuinely Arab Bedouin tradition’. But in reality, most of the indigenous tribes of Qatar were sedentary, and are more often than not of mixed ethnicity.

Of the non-sedentary tribes who grazed their stock in Qatar, the majority was merely transient. They owed allegiance to the Saudis, whom they paid jizya (tribute). Individual clans of the great Bedouin tribes such as the Al Murra, Bani Hajir and the Manasir nevertheless succeeded in acquiring the Qatari nationality.

Some of them even managed to secure a double nationality, enabling them to continue their seasonal migration between Saudi Arabia and Qatar.

Of the more indigenous Bedouin tribes, al-Nuaim, numbering about two thousand in 1908, were by far the largest group. From about 1860 their dira or grazing area was located in the hinterland of al-Zubara. Part of the tribe was sedentary, but the majority was pastoral. In the summer a large group of the Nuaim would migrate by boat – with their camels, horses and sheep – to Bahrain.

Others took up summer quarters near Doha. In the late 1950s, there were only about a thousand Bedouins still living in tents in the whole of Qatar. In 1960, the government started a settlement programme, urging the remaining pastoral Nuaim to exchange their tents for the concrete houses of the newly built town of al-Ghuwayriya.

The majority of tribes in Qatar settled as town dwellers or hadar (people leading sedentary lives) in the 18th century. They generated income mainly from pearl diving, fishing, trade and sea transport. Their economy was therefore oriented more towards the sea than to the desert. Besides, they owned camels, sheep, and goats, which were herded by Bedouins of the interior in the winter months.

Some of the hadar tribes also took to the desert themselves during the colder season. Their main objective was the grazing of their stock, but there may also have been a political motive. For example, Al Thani sheikhs used their desert camps to assert influence over the Bedouin tribes of Qatar.

Mixed Ethnicity

From the 18th century until the start of the oil era in 1949, most inhabitants of Qatar were Sunni Arabs who had at some point in history migrated there from Central Arabia, although often by way of a temporary settlement elsewhere.

At the beginning of the 20th century, there were also five hundred Bahraini, mainly Shia Arabs (mostly from Bahrain) and two thousand Huwala (Sunni Arabs from Persia) living as boat builders or merchants in Doha and al-Wakra, as well as 450 Shia Persian artisans and merchants.

By 1939, the number of Persians had increased to about five thousand, or almost 20 percent of Qatar’s population at that time.

The Sunni Arabs did not intermarry with these migrants, but they did have offspring from East African, Baluchi and Indian slave girls. When the British started to suppress maritime slave transports in the Gulf in the 19th century, young slave girls – between eight and fourteen years old – were brought to Qatar mainly overland by Qatari traders based in Oman and the present United Arab Emirates.

As late as 1942, Sheikh Abdullah bin Jassim Al Thani sent Ibn Saud twenty Baluchi concubines as a personal gift. Because of this intermingling of Arab and foreign races through the system of concubinage or ‘second wives’, the Gulf region has recently been called a ‘considerable cultural melting pot’ by the Zanzibari historian Abdul Sharif.

Black slave girls and their offspring are but one African element in Qatar’s national population. Many of the pearl divers were black slaves or former slaves, who had been captured by Arab-African slave traders from the Omani colonies in East Africa. In 1908, the British estimated that two thousand ‘free negroes’ and four thousand black slaves ‘not living in their master’s house’, were living in Qatar.

To this subtotal, an unknown number of slaves living in their owners’ households must be added. With a population of only 27,000 in the early 1900s, the estimated portion of pure Africans in the native population must have reached at least 22 percent.

Black slaves were among the first workers in the oil industry. They were paid in cash by the oil company but had to hand over 80 to 95 percent of their wages directly to their masters. Slavery in Qatar was only officially abolished in 1952. The former slaves seem to have blended into society relatively smoothly. These days former Qatari slaves and their offspring can typically be found in security and army jobs, and the dance and music sector.

Non-Citizens

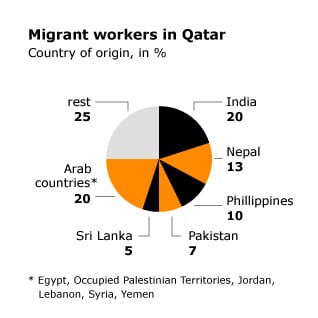

The Anglo-Persian Oil Company’s (APOC) 1935 oil concession required that the oil company give hiring preference to Qataris. But when production on a commercial scale began in 1949 (through APOC’s subsidiary Petroleum Development Qatar Ltd.) there were not enough Qatari labourers to work in the oil industry. A shortage of skilled labourers was especially felt since schooling in Qatar was only accessible to small groups and of a traditional nature. In the mid-1950s there were only about 600 indigenous literates in Qatar. As a consequence, the oil company had to hire expatriates on a large scale. Two types of migrants – ‘professional’ and semi- or unskilled migrants – emerged, which was in effect a continuation of the pre-oil pattern of migration.

The former social position of the black male slaves and poor Arabs was now filled by non- or low-educated Pakistanis, Indians, Omanis, Yemenis and a small group of Saudis. They came to work not only for the oil company but also in construction and agriculture. In the oil industry, this led to clashes between nationals and the new migrants in the early 1950s, with the first group demanding – and receiving – preferential treatment. Such tensions did not exist in construction and agriculture as most Qataris refused to work in these sectors. To this very day, construction and agriculture in Qatar are almost exclusively the domain of foreign workers and managers.

When oil money started to flow freely after 1973, Asian migrants found work in new fields such as transport and other services. Migrants from Nepal, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, the Philippines, China, and Indonesia joined the older migrant nationalities. The Nepalese currently form the second-largest Qatari migrant group, with an estimated community of about 150,000 members, behind the Indians (roughly estimated at 200,000).

In 2008, Amnesty International reported: ‘Foreign migrant workers, who make up a large proportion of Qatar’s workforce, complained that they were exploited, including by non-payment of wages. They continued to have inadequate protection under the law. In May, hundreds of Nepalese workers staged protests to demand an increase in and monthly payment of their salaries and benefits. They were reportedly arrested and ill-treated before being deported to Nepal.’

The Human Rights Report 2008 of the US Department of State noted: ‘Although the labor law provides the Emir with authority to set a minimum wage, he did not do so. The average wage of non-citizen workers did not provide a decent standard of living for a worker and family. (…) Many such workers frequently worked seven days per week and more than 12 hours per day with few or no holidays, no overtime pay, and no effective means to redress grievances.’

Furthermore: ‘The rights of non-citizen workers continued to be severely restricted. Some employers mistreated foreign domestic servants, predominantly those from South Asia, Indonesia, and the Philippines. Such mistreatment generally involved the nonpayment or late payment of wages and in some cases involved rape and physical abuse.’

Some foreign embassies provided temporary 48-hour shelter to nationals who had left their employers as a result of abuse or disputes before transferring the case to local government officials. According to their embassies, the majority of cases were resolved within 48 hours.

Those not resolved within 48 hours were transferred to the Criminal Evidence and Investigation Department of the Ministry of the Interior for a maximum of seven days. Cases not resolved within seven days were transferred to the labour court, a special section of the first instance civil court.

A considerable portion of the new group of Asian migrants consists of women hoping to work as domestic servants, nannies or waitresses. According to the UN Special Rapporteur on Trafficking in Persons, these girls are often confronted with forced labour – including work on farms in Saudi Arabia – and sexual exploitation.

There is also a relatively substantial white-collar class of educated Egyptians, Palestinians, Jordanians, Lebanese, and Syrians. Following the Labour Law, these skilled Arab migrants have to be hired in preference to other foreigners.

They generally work as teachers, civil servants, doctors and engineers. The most influential and affluent – although by far the smallest – migrant group, however, originates from Europe, the United States and Australia. These well-paid and well-cared-for professionals are collectively known as ‘expats’.

They live in the relative seclusion of western compounds or districts and generally consider their sojourn in the Gulf as temporary. Only recently has their luxurious position been threatened by professionals and entrepreneurs from the new economic powerhouses of Asia: India and China.

Position of Migrant Workers

For its infrastructural development, Qatar, like other Gulf states, has depended on the influx of migrant construction workers from poorer Arab countries, South-East Asia and the Far East. Qatar’s treatment of these low-skilled labourers, who have flocked to the country in search of paid labour, has recently been in the international spotlight. More than half a million migrant construction labourers were working in Qatar in 2010, according to the 2010 census.

In June 2012, Human Rights Watch (HRW) published a report Building a better World Cup on the working and living conditions of foreign labourers in Qatar. HRW warned that workers, attracted by new projects in Qatar, are in danger of maltreatment, abuse and violations of their rights. The International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) characterized the living and working conditions as ‘inhumane’ in its 2011 report Hidden Faces of the Gulf Miracle.

These reports exclude higher-level employees, often from the West, who live and work in very different conditions. The position of migrant construction workers in Qatar had already been under scrutiny in earlier reports by Amnesty International and the US Department of State (2008).

Problems often start with the recruitment process in the country of origin, where workers have to pay high fees to recruitment companies. This forces them to enter into loan agreements at high-interest rates, even before they get the chance to earn money. Many foreign labourers are promised high salaries but face deception as soon as they arrive in Qatar. Many are trapped in jobs they never agreed upon or get paid much less than expected.

To be able to work and stay in Qatar, workers are dependent on their local sponsor, a Qatari citizen or institution, due to Qatar’s restrictive sponsorship kafala system. As the sponsor is legally and financially responsible for the employee, the employee cannot change jobs or leave the country without his sponsor’s consent.

Part of a policy to strictly control (the influx of) migrant workers, this system effectively traps workers in their jobs, making them vulnerable to abuse and exploitation and restricting freedom of movement. As employees are often not in the possession of their own passports, this amounts to forced labour, HRW has argued.

Also, underpayment, late-payment and even non-payment have been reported as workers’ main complaints. In a study by the Qatar Human Rights Committee, 33.9 percent of workers surveyed said they were not paid regularly, although the Qatar Labour Law requires companies to pay workers every month.

Many workers did not receive their salaries for up to three months. Employers are also known to illegally deduct wages to pay for costs including visa fees, food and medical insurance. While the government announced wage increases for Qatari employees, foreign workers’ salaries have not kept pace with rising food prices. Most migrant construction workers live in labour camps on the outskirts of the city, kept far away from the glittering waterfront of Doha.

While some companies offer their employees good facilities, many workers live in cramped, unsanitary accommodation in miserable conditions, lacking facilities like water and air conditioning. The palm-lined Corniche and luxury shopping malls are off-limits to migrant workers, where they are denied access on their only day off.

In addition to inadequate housing facilities, workers often enjoy insufficient protection against safety hazards on the construction sites. Workers are exposed to dangers including extreme heat, equipment malfunctions and accidents on building sites. Data on workplace injuries or deaths are not publicly reported. ITUC recorded 162 deaths among workers from Nepal in Qatar in the first ten months of 2011, which were often left unexplained.

While the Qatari Labour Law of 2004 requires employers to set maximum working hours (Article 73), pay workers on time (Article 66), prohibits employers from charging recruitment fees to workers (Article 33) and requires them to report injuries and deaths (Articles 108, 115), accounts of HRW and ITUC demonstrate that the law is not adequately enforced, due to inadequate monitoring of companies and workers’ labour and living conditions.

HRW has warned that Qatar’s current system of labour inspection and systems of complaints reporting fail to provide effective protection against abuse and exploitation. Although the government has taken steps to increase workers’ awareness, effective reporting and enforcement mechanisms are absent. Employees who complain face the risk of immediate termination of employment. Besides, Qatar has no minimum wage and bans workers from forming labour unions. Membership of workers’ unions is confined to Qatari workers (Article 116, Qatar Labour Law).

Faced with international criticism, Qatar has announced steps to improve conditions of migrant labour, including tighter rules to control recruitment agencies, improving safety standards and better housing. In May 2012, the government announced moves to scrap the sponsorship system and replace it with contracts between worker and employer.

However, the sponsorship system has not been annulled as of September 2012. The position of migrant construction workers in Qatar has started to raise attention since Qatar won its bid to host the FIFA World Cup Football Championship in 2022, for which huge infrastructural projects have been announced.

Islam in Qatar

Islam is the state religion of Qatar. Its ruling Thani family is known to follow the austere teachings of the Wahhabi sect, which is a puritanical offshoot of the Hanbali school of Sunni Islamic Law. Originally, the indigenous tribes of Qatar adhered to the Maliki school of Sunni Islamic Law.

However, there were some exceptions, as a few inhabitants were considered adherents to the three other currents in Sunni Islamic Law: orthodox Hanbali, Hanafi or Shafii. The visiting tribes of Bani Hajir and Al Murra were all Hanbali, although in 1908 the British diplomat Lorimer asserted that the Murra clan ‘concern themselves little with religion’.

According to Lorimer, Al Thani patriarch Jassim bin Mohammed Al Thani was the first of the Maadid tribe to embrace the Hanbali – in effect Wahhabi – creed.

Contemporary publications on Qatar almost invariably claim that all of its non-Shia citizens are Wahhabi Muslims. However, such statements are not entirely reliable, as freedom of religion in Qatar is only relative. Moreover, as in most traditional and authoritarian societies, people tend to keep up appearances in public.

It is clear however that most Qatari citizens – about 90 percent – call themselves Sunni Muslims; also, a minority estimated at 10 percent is Shiite. The Shia have their own mosques but refrain from ceremonies in public. Converting from Islam to another religion is considered apostasy and is a capital offence according to Qatari law. However, no case of apostasy has been recorded since Qatar’s independence in 1971.

Latest Articles

Below are the latest articles by acclaimed journalists and academics concerning the topic ‘Population’ and ‘Qatar’. These articles are posted in this country file or elsewhere on our website: