A violent response to the coup was soon to follow. What began as sporadic attacks on military personnel and policemen grew into an armed struggle by a variety of Islamist groups that cropped up all over the country. The core of the armed groups was formed by Algerians who had fought in Afghanistan against Soviet troops. They were joined by radical ex-members of the Islamic Salvation Front (Front Islamique du Salut, FIS).

It soon became clear that neither the army nor the Islamist armed groups could win. The cycle of repression and attacks soon degraded into all-out violence, mainly against civilians. The emergence of the Armed Islamic Group (Groupe Islamique Armé, GIA) was a symptom of this. GIA gunmen, or those hired by them to do the killing, attacked dozens of journalists, artists, and intellectuals whom they considered ‘enemies of Islam’.

In order to regain control of the guerrilla war, underground and exiled FIS leaders created the Islamic Salvation Army (Armée Islamique du Salut, AIS) as a military wing. Islamist groups belonging to both the AIS and GIA managed in the mid-1990s to gain control of parts of the mountainous areas of the north.

Eventually, they were dislodged by the army, which had been reinforced by materiel from France and other countries. The intelligence services were reported to have infiltrated the armed groups. The military establishment succeeded in striking a deal with the AIS in 1997. The truce involved a ceasefire in exchange for the rehabilitation of the Islamist fighters, who in some cases even helped subdue their adversaries in the GIA.

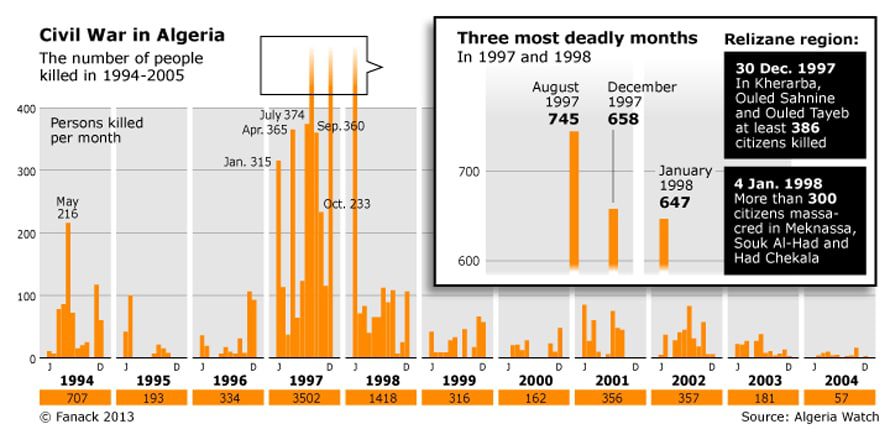

This situation led at first to a period of extreme violence. Entire villages were massacred by armed attackers, actions the GIA said were to punish disloyal groups and communities. Some observers hinted at the role of the army, which was accused of failing to act against the perpetrators or even of being involved in war crimes in order to discredit the Islamists.

What is certain is that the war was partly ‘privatized’ by the creation of pro-government militias throughout the country. They received arms from the military and were meant to fulfill an auxiliary role. In practice, the militias often represented the interests of local strongmen and were responsible for at least some of the atrocities. Also contributing to the continuing violence were criminals who sought to protect their interests from the powers of the state. The 1997 armistice, the better equipment of the army, and the co-optation of former guerrillas gradually began to pay off for the state leadership.

The developments on the battlefield coincided with steps by the military to break the political deadlock and regain some of the legitimacy they had lost in the domestic and international arenas, after the cancellation of the elections. At first, these efforts failed miserably.

The installation, in January 1992, of exiled FLN-leader (National Liberation Front, Front de Libération Nationale), Mohamed Boudiaf as president of the ruling state council seemed initially to be a masterful move, but Boudiaf was assassinated by a bodyguard on 29 June 1992. This killing was widely believed to follow Boudiaf’s intention to eradicate corruption.

Other attempts to give a civilian face to military rule did not at first produce results, either. Successive heads of the state council tried either to pursue economic restructuring or to turn back such measures, but neither approach gained them credibility with the people.

The result of the continuing war and political stagnation was that even the leadership of the FLN party apparatus turned against the military.

In 1995, the FLN concluded the Treaty of Rome with the exiled FIS leadership and the secular, Berber-dominated Socialist Forces Front (Front des Forces Socialistes, FFS). With this agreement, the three ‘fronts’ aimed to obtain domestic and international support for ending the civil war and returning to democracy. This forced the military to come up with a political initiative as well.

In 1996, the presidential election was won by General Liamine Zéroual, who also created a political party as an alternative to the not-always-reliable FLN party barons. This National Democratic Rally (Rassemblement National Démocratique, RND) would be a vehicle for regaining legitimacy for a tarnished political system.

In 1997, the Algerian population voted for a new Parliament. Although this election was widely regarded as an effort to erase the 1991 victory of the FIS, many opposition parties decided to take part. The victory of the newly founded RND surprised no one. The real novelty was the formation by the RND of a new coalition government that also included both the secularist hardliners of the Rally for Culture and Democracy (Rassemblement pour la Culture et la Démocratie, RCD) and the Islamist Movement of Society for Peace (Mouvement de la société pour la paix, MSP), which had always opposed the FIS.

By the turn of the millennium, the civil war, as such, had come to an end. The army prevailed, although attacks on military convoys and government institutions continued in the following years.

In 2007 there was a major bomb attack on the United Nations office in Algiers. In addition, some of the Islamist groups declared themselves part of al-Qaeda and aimed to join forces with militants from elsewhere in North Africa. Attacks on security forces continued throughout the country.

Nevertheless, the founding of al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (al-Qaïda au Maghreb islamique, AQIM) seemed to represent a weakening rather than a strengthening of the armed Islamist movement. Having emerged from groups in the north, AQIM became notorious for the kidnapping of tourists and other criminal acts in the Saharan regions of Algeria and its neighbouring countries.

Most of these activities took place along or outside Algeria’s southern borders, which have always been the domain of smugglers, as cross-border movements are difficult for the authorities to control. The question remains whether there is a clear political project behind AQIM. The fact is that kidnapping foreigners and involvement in the drug trade from Latin America through West Africa to Europe (as well as illegal migration) are attractive sources of revenue for anyone who controls part of the territory. In addition, the situation that emerged in neighbouring northern Mali in 2012 showed another pattern of convergence and divergence between Islamist and other political projects (in this case, the Tuareg independence movement).