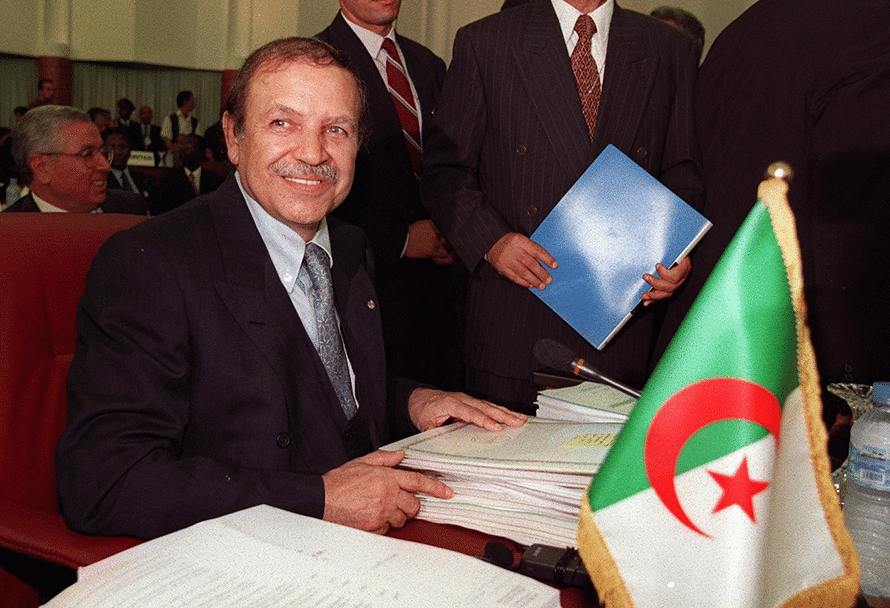

In 1999 the military leadership succeeded in enlisting a strong civilian political personality as a candidate for the presidency. Although he had lived in Switzerland and the Gulf States in the 1980s, Abdelaziz Bouteflika was by no means a newcomer to the Algerian political scene.

In 1963, at age twenty-six, he had been the first Algerian Minister of Foreign Affairs (and the youngest ever internationally). After the death of Boumedienne in December 1978, he had been a candidate of the FLN’s (National Liberation Front, Front de Libération Nationale) liberal wing to succeed him. After his election in 1999, Bouteflika promised to end the ‘black decade’ by a programme of ‘peace and reconciliation’.

This included not only guarantees against prosecution of Armed Forces-personnel and pro-government militias but also pardons for groups of Islamist combatants; Bouteflika introduced two laws to this effect. Given widespread despair and longing for an end to the bloodshed, many Algerians supported him in this policy, but human-rights groups and especially organizations of families of ‘disappeared’ people continued to struggle against the covering up of crimes and against the impunity of their perpetrators that were the effects of the amnesty. The impact of the civil war and the effect of the policies of economic liberalization that had been pursued during the 1990s caused socio-economic imbalances.

Although macro-economic indicators, particularly the country’s foreign debt, gradually improved, this was generally not the case for the living conditions of much of society. The crises of insufficient housing, inadequate infrastructure, and lack of employment that disproportionally affected the youth had not been resolved since these factors had fuelled the escalation in political conflict beginning in the 1980s.

Restoring the rulers’ legitimacy therefore also involved addressing these potential sources of new unrest. Bouteflika launched a large-scale investment programme, with increased state expenditures on infrastructure, housing, and employment. In addition to new highways and railroads, the plans envisaged the construction of one million houses. The realization of these ambitious intentions was made possible only by the increase in revenues that accompanied the rising global demand for petroleum products and natural gas beginning in 2000. Over the next decade, the nation enjoyed an impressive trade surplus.

Bouteflika was re-elected President in 2004 and 2009. The election process brought growing protests by the opposition. Disagreements on procedures often led opposition candidates to withdraw or to call into question the results of the vote. The same applied to the elections for Parliament. In the spring of 2012, these were won by the FLN. More important to many observers was the shrinking participation in the elections.

At the fiftieth-anniversary celebration of independence, stability appears to persist. This is in spite of the social-protest movement of 2011, coinciding with the ‘dignity revolutions’ in neighbouring Tunisia and Egypt. Protests erupted mainly over rising food prices, but, because this issue had also played a role in other Arab countries, some opposition movements saw an opportunity for more demonstrations.

The parties and other organizations involved were, however, divided in their approach and over who should take the lead. Because of political differences, an attempt to form a joint committee of various civil-society organizations and activists did not get off the ground. The government, on the other hand, was bent on preventing the escalation of the protests. As a result, a relatively small demonstration organized by the Rally for Culture and Democracy (Rassemblement pour la Culture et la Démocratie, RCD) failed because of the inaction of other parties, a lack of public interest, and a show of strength by an overwhelming police force.

The main reasons for the unsuccessful protests were the attitude of the public and their memories of the civil war. The desire for change is weakened by the fear that a protracted period of protests will end in repression and violence and might even revive the past situation. And, in contrast to Tunisia under Ben Ali, social protests and rioting were already taking place throughout Algeria, albeit on a limited and local scale.

The 2011 civil war in Libya worried the Algerian leadership, as it feared that arms would fall into the hands of remaining Islamist armed groups that operate in countries in the Sahara and the Sahel.

The armed uprising of 2012 in northern Mali, which borders southern Algeria, seemed to justify those concerns. Well-armed groups of Tuareg fighters and Islamists succeeded in holding the territory, causing concern in African and Western capitals. At the beginning of 2013 the situation escalated, and France decided to send troops to Mali. Despite earlier opposition to Western intervention, Algiers granted French aircraft free passage through its airspace. The rapid ouster of the rebels from the main northern Mali cities did not, however, spell an end to the violence.

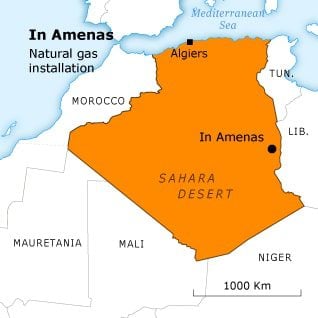

In January 2013, an Islamist armed group led by a former AQIM (al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, al-Qaïda au Maghreb islamique) leader captured a natural-gas installation at In Amenas and took scores of hostages, including many foreign workers. Algerian forces ended the hostage-taking in a few days, with overwhelming force; the operation took the lives of many hostages, including thirty-seven foreigners.

Although the link with the Mali crisis is not clear – the attack is thought to have been planned earlier and did not involve the same Islamist factions as in Mali – the violent events in the Sahara and the Sahel pose a clear security challenge for Algeria and emphasize the urgency of reconsidering its strategies vis-à-vis neighbouring countries, the various armed groups (political and criminal), and Algeria’s relationship with the West.