Introduction

Algerian society is characterized by a Berber/Arab identity with fading French influences – the inheritance of over 130 years of far-reaching French colonization. The dominant secular legacy dating from the first decades of the Republic has since been challenged by the Islamists, who have won substantial support amongst layers of society. As elsewhere in the region the Algerian rulers are grappling with the tensions caused by the fact that the rate of population growth is incongruent with the country’s economic development. Poverty and discontent are the result.

Clans and Communities

Since the war of independence, the Algerian population has had a strong sense of national belonging. The experience of that war, which is transmitted both through the educational system and more informally, has strengthened the idea of nationhood. The economic integration of the country, its imperfections notwithstanding, has brought people from the various regions of the large country into more contact with each other. Regionalism is, however, still an important factor in Algerian social and political life. The regional origins of the President and other state leaders, for example, are considered significant. There has always been a rivalry between the elites from eastern and western Algeria. Smaller groups, such as the Tuareg or the Ibadis of the Saharan region, are left out of this equation. There is also competition between Arabic and Berber-speaking regions, although this involves mainly Kabylia and its relationship to the power centre of nearby Algiers. In both cases, the tensions overlap with other factors, and social and political leaders from the same region have often exhibited strong differences – for example, the contrasting orientations of the so-called Berber parties (the Socialist Forces Front (Front des Forces socialistes, FFS), and the Rally for Culture and Democracy (Rassemblement pour la Culture et la Démocratie, RCD)), and the differences between the two parties and the local social movements that appeared in Kabylia beginning in the 1990s. Many politicians also have client networks.

Family

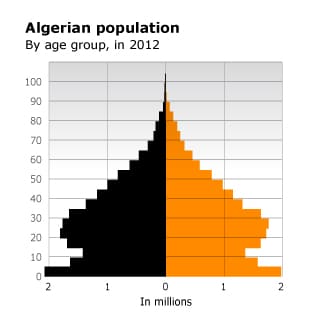

The size and structure of Algerian families have undergone many changes over the past decades. As fertility fell from about 3 percent in the 1970s to about 1.7 percent three decades later, the average size of families also fell. With urbanization has come a larger role for the nuclear family as compared with the extended family, which predominated in earlier decades, but there are significant differences according to class and between urban and rural families. With the increase in education for girls and the increasing role of women in the labour market, the average number of children per family has been declining for the past twenty years.

Women

The position of women has always been a major social and political issue in Algerian society. Despite the role of women in the war of independence and the subsequent socialist course of the government, there are still inequalities in many domains, and there are great differences in the way women lead their lives in various social classes and regions. Women’s-rights activists have been making themselves heard in Algerian politics and have rallied mass movements to their cause, but the impact of their actions has been limited.

The position of women has, however, changed significantly over the years, due mainly to developments in the wider society, especially compulsory education for girls and the success of women in higher education and improvements in women’s reproductive health. Improvements in education and employment opportunities for women have led to smaller families. Daughters and sons now have different role models from those of earlier generations, who grew up in far more patriarchal traditions.

Politically, the women’s movement is divided over important issues. In the 1980s women from many different tendencies found themselves opposed to the so-called Family Law, which threatened to harm the position of women on issues such as marriage, divorce, and inheritance. In marriage, women were obliged to be accompanied by a male ‘guardian’, and women’s rights at inheritance were inferior to those of men. Ten years later, polarization around elections and the role of Islam divided the mainly secular women activists. This was not surprising, given the division on the issue that became apparent in attitudes on the 1992 military intervention in politics and civil society. Some former activists, such as Khalida-Toumi, sided with the government; she eventually became Minister of Communication and Culture, a move fiercely opposed by other women.

Youth

Because of the population boom in the previous two decades, the youth of Algeria became Algeria’s majority in the 1980s. At the same time, the economic crisis and various structural developments led to a shortage of jobs, housing, and entertainment. It was no surprise, then, that the October 1988 uprising was conducted mainly by the young. A small but significant number later joined Islamist armed groups. For the most part, though, young people have seemed doomed to wait and see or take the risky step of illegal migration to Europe. Surveys of youth regularly show that many young people desperately want to move abroad in search of a better life and all the things that are not available at home, but only a small minority succeeds in that endeavour. Contrasted with the image of the h arraga (those who burn their immigration papers upon capture) is that of the hittiste (one who hangs to the wall, hit ).

Education

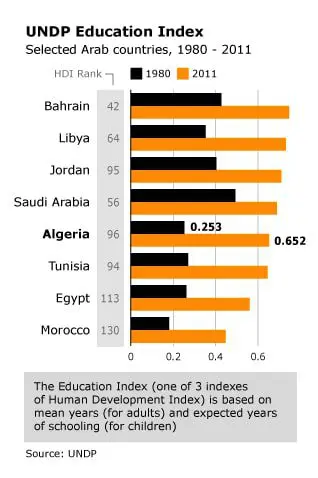

Because of the introduction of compulsory education in the 1970s, 90 percent of Algerians have been enrolled in school. This has resulted in a sharp decline of illiteracy: from a mere 21 percent in 1970, about 75 percent of the population can now read and write. Women, though, still lag behind, because, in the past, most had no chance to attend school. Nowadays, girls are better performers than boys, as they make up the majority of pupils in higher education. In 2008 the number of women in institutions of higher education was almost 1.5 times that of men, up from about one-quarter in 1970.

The educational system still bears traces of the colonial past. It strongly resembles the French system – a nine-year primary school, followed by vocational training or a lycée in preparation for university. Academic education is entirely subsidized, and the government has invested heavily in the creation of 25 universities across the country. Together with dozens of other establishments for higher education, they attract more than one million students. The social sciences are most popular (40 percent of students), almost twice the rate for natural sciences and engineering. Third are education and humanities (16 percent), followed by medicine (7 percent).

French has remained an important language of instruction, despite the state’s early attempt at the Arabization of the educational system. Soon after its formal introduction, this planned conversion of the entire curriculum proved unrealistic. Not the least of problems was that many graduates educated exclusively in Arabic had more difficulties finding employment in the government or in state-run industries, where a mastery of French and other foreign languages was an advantage. The frustration of these arabisants later became a factor in the rise of the Islamist movement. In the neighbouring countries that have recently undergone political revolutions, especially Tunisia, the connection between higher levels of education and higher unemployment has been an important factor in the rise of Islamism. In Algeria, the rate of unemployment among youth is twice the overall figure and is even higher among university graduates.

The ideological connotations of the language issue have led the state to follow a cautious course. As a compromise, Arabic is taught exclusively until the third year, when children also begin to learn French. The teaching of other European languages (English, Spanish, Italian) is encouraged in order to de-emphasize the ‘culture war’. At the universities, French is dominant, especially in the natural sciences. Since the recognition of the Berber language, there are more opportunities for learning Tamazight.

Although the state aims to provide universal access to education, many parents resort to private schools. The latter are not formally permitted, but, in practice, they are crowded with children from affluent and influential families who have good relations with those in power.

Health

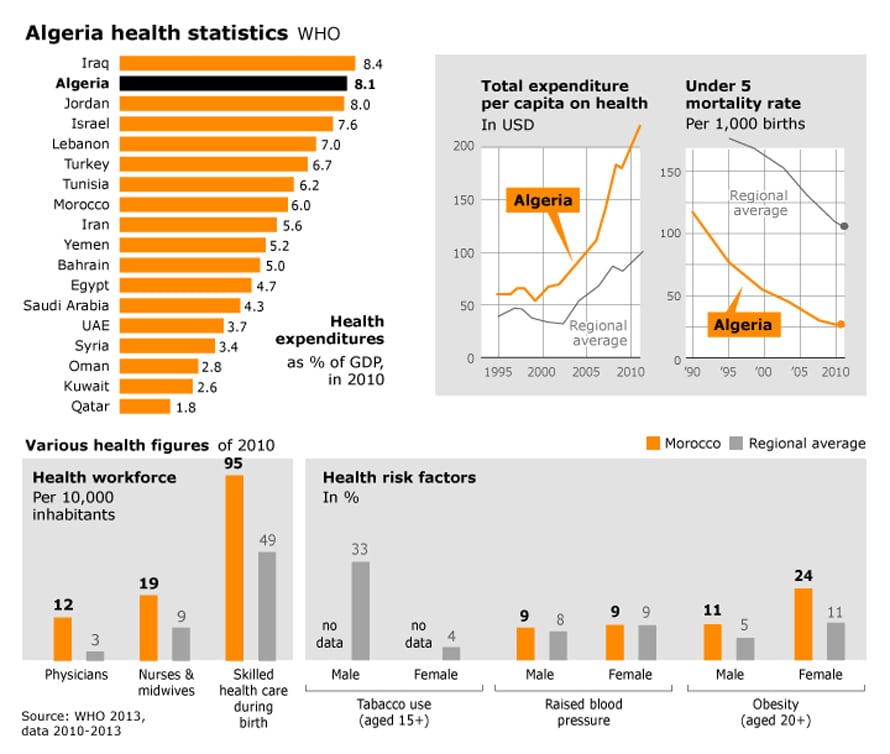

Providing all Algerians with access to health care was one of the priorities of the post-colonial state. The system, which has been free of charge since 1975, is relatively advanced. It includes medical faculties at the universities, as well as schools for nurses and other auxiliary personnel. The state also guarantees the availability of preventive care and treatment in remote areas. Doctors and dentists are required to serve in oasis towns or in villages on the High Plains for the first five years after their graduation, before being allowed to return to the big cities that they often prefer.

The strong growth of the population after 1962 has led to the establishment of more preventive-care centres, instead of just new hospitals. Over the years, prevention has brought a sharp reduction in infant and child mortality.

In the last decade, prevention has also included measures against the spread of HIV/AIDS. Although Algeria and the North African region are not a major risk area for the spread of the disease, it appears that it may be on the rise there. One of the factors behind this may be prostitution in the main transit towns along the Saharan routes. A more general risk is the taboos surrounding sexuality that prevail in large parts of society, especially those concerning premarital sex and homosexuality, so the government has instituted information campaigns and has opened centres for testing (anonymous and free) in many towns and cities.

Social Protection

The state provides a basic social-security system for the unemployed and guarantees minimum wages. About 7 percent of the state budget is allocated to social services, including unemployment benefits and grants for the education of unemployed youth. Old-age pensions include benefits for former fighters (mujahidin) in the war of independence, with benefits administered by the independent Ministry of Former Mujahidin. The problem is that these benefits do not rise as fast as the cost of living. This is especially true of the many items that are available only as imports. About one-fifth of the population is uninsured against illness and other health risks or labour-related injuries. As a result, informal networks, especially one’s family, are important for the lower classes.