Introduction

The Algerian political system and the state’s administrative structure have been remarkably stable since independence in 1962. At the same time, many imbalances that resulted in the political and economic crisis of the 1980s and the subsequent civil war have persisted.

Amongst the institutions that have maintained stability, the military and security apparatus is the strongest and predates independent Algeria. It is the main player in the political game, either directly or indirectly. The army’s predominance followed from the intransigence of the French and their obstruction of more reformist ways of extending the native population’s rights, which left armed struggle as their only practical option. This does not mean that other institutions are irrelevant. The state’s administrative system, with all its weaknesses, does function, extending to the level of local communities in every corner of the country. Some institutions, such as the diplomatic services, have proven particularly successful. The economic system has structural shortcomings but has been able to keep the main processes running, in particular those related to the oil and gas sector, and to improve the infrastructure. It is rather that the functioning of many state structures is ultimately subordinated to decisions made by the politico-military establishment, which consists of a small group of the heads of the Armed Forces and the intelligence services.

Colonialism and the war of independence also brought with them a sense of national identity that had been weak before 1830. In the Berber cultural movement, for example, the emphasis is on the definition of the Algerian identity, not on promoting a separate state.

Algeria’s leaders have sought to maintain stability by the use of revenues from oil and gas in the international market. Especially after the huge increase in oil prices in the 1970s these funds not only helped build the economy but also served to legitimize the rule of the state leadership emanating from the army and the governing party, the National Liberation Front (Front de Libération Nationale, FLN). Together with the industrialization programme and the building of a physical infrastructure, the creation of employment and basic social services strengthened the state’s claim that it was fulfilling the promise of a better life that it had made the population.

With each generation, the experience with the war of independence has faded further, but this does not reduce the importance of this legacy for Algerian politics. Many leaders, in both the regime and the opposition, still claim legitimacy by referring to their role in the independence movement, and many Algerians have the special social status of a former fighter in the war, or mujahid. The extent of this phenomenon appears from the fact that more than 1 million people receive a war pension, consuming USD 2.3 billion annually. Nationalism and an aversion to foreign intervention are still part of the worldview of most politicians, including those belonging to the post-war generation. Over the years it has, however, become far more difficult for state leaders, political parties, and state institutions to appropriate the idea of nationhood for the promotion of their own interests. While the sense of national identity still holds for most Algerians, the credibility of its self-proclaimed defenders has often been tarnished. This was one of the reasons that, with the introduction of a multiparty system in 1989, the FLN could not play the nationalist card against the Islamic Salvation Front (Front Islamique du Salut, FIS). The Islamists claimed themselves to be the true representatives of the Algerian revolution, whose intentions they saw betrayed by the ‘corrupt’ former state party.

The sudden abolition of the single-party structure and the subsequent catastrophe of civil war emphasized the limits of the resources and capabilities of the political system. The crisis showed the absence of credible institutions mediating between the state elites and the people. It proved that the dependence on oil and gas revenues was not a sustainable basis on which to maintain state and social relations, as the state’s power fluctuated with prices on the global markets, and it hinted at the incapacity of the upper echelons of the state to manage the crisis successfully, without piling one disaster on another.

Two decades on, the system and its leadership seem incapable of resolving these fundamental issues. Opposition parties are allowed to compete in elections, but they are unable to gain significant power on account of the way the system functions and the fact that the military and security establishment still decides important issues. There is extensive freedom of the press to criticize those in power, but it is not unlimited. The enormous increase in civil-society organizations has not given citizens more influence on the political process, but rather appears to be another mechanism of control. The political system has been largely unable to eliminate the widespread distrust of the population, even as the resurgence of oil-related income enhances, at least somewhat, the ability of the state to fulfil those needs.

The Executive

Algeria has a presidential system. Most presidents so far played a role in the independence movement and the National Liberation Front (Front de Libération Nationale, FLN). Perhaps more importantly, the president has always either been a member of the military establishment or been endorsed by the army. This does not mean that the heads of state have lacked popular support.

Formally, the President has substantial powers and may overrule other power centres. In reaching decisions, he has to agree with the heads of the military and security apparatus. This makes the Algerian system a far more collective enterprise than those of many other countries in the Middle East and North Africa, where the President personifies the system. It appears that this state of affairs has actually strengthened the position of the President and the entire system. Protesters and political opponents, for example, usually demand changes in what they refer to as le pouvoir (the power), instead of demanding the resignation of the President, as they expect that change at the top does not fundamentally alter the workings of Algerian politics.

The first head of state of independent Algeria was President Ahmed Ben Bella, a civilian and one of the nine ‘historic’ leaders of the FLN, who ruled from 1963 to 1965. He owed his position to his alliance with the liberation army headed by Colonel Houari Boumedienne. Although his position was initially the result of the struggle for power among the various factions in the liberation movement, Ben Bella obtained a clear popular mandate. In the 1962 presidential elections, the enthusiasm for a state headed by one of their own people for the first time resulted in a huge voter turnout.

Ben Bella, who died in 2012, had to function as head of state by balancing various political forces that disagreed strongly about the country’s political and economic orientation. In these circumstances, and in comparable episodes in the subsequent decades, presidents with a military background took charge, to the detriment of civilian candidates. This was the case with Ben Bella’s former ally and Defence Minister Boumedienne (1965-1978), who ousted Ben Bella in a bloodless coup in 1965. In order to put an end to political chaos, President Boumediene wanted to remove the existing institutions in order to be free to build new ones that would express his vision of Algerian socialism and eliminate the earlier infighting.

After Boumedienne’s sudden death from illness in December 1978, the military establishment appointed their supreme commander, Colonel Chadli Bendjedid (1979-1992), as his successor. The coup of 1992 showed that it was again the military that decided the rules of the political game. For some years, the presidency was in fact assumed by the chairman of the High State Council. The failure of this institution to produce a political breakthrough during the civil war paved the way for General Liamine Zéroual (1994-1999).

Abdelaziz Bouteflika

A new series of elections marked the beginning of the rule of Abdelaziz Bouteflika (1999-present). The former Minister of Foreign Affairs was re-elected four times, albeit in contested elections. In the summer of 2012 there were rumours in the Algerian press about the creation of the post of Vice-President.

Given earlier health problems that forced president Bouteflika to reduce his tasks, this might well be a way to guarantee continuity should the President be unable to function.

The President wields the main executive powers and is supported by the Prime Minister and the Council of Ministers. Abdelmalek Sellal was appointed Prime Minister in September 2012.

Since the restoration of the multiparty system in 1997, most cabinets have been coalitions between the ‘institutional’ parties FLN and RND (Rassemblement National Démocratique, National Democratic Rally) with one or more Islamist and secular parties.

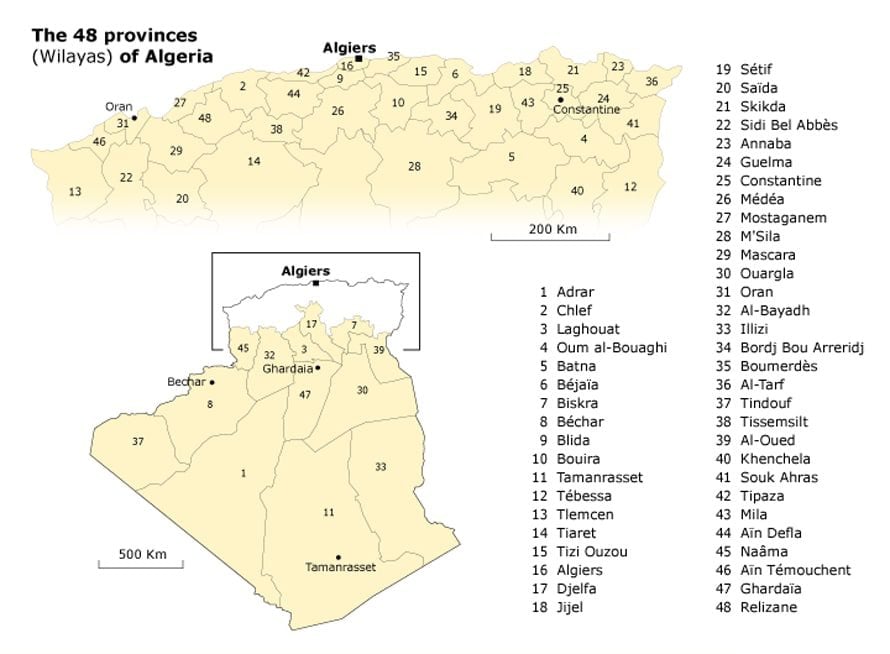

The Legislative

Algeria has a bicameral Parliament. The 462-member Lower Chamber, or People’s National Assembly (Assemblee Populaire Nationale), is elected directly. The Senate or Council of the Nation (Conseil Nationale, 144 seats) comprises representatives from the country’s provinces (wilayat, sing. wilaya); one-third of the members are appointed by the President. The Senate has the power to block legislation of the People’s Assembly. This strong position of the Senate is due to constitutional changes after the civil war in the 1990s that were intended to prevent a strong opposition party from overruling the presidency.

In the 2012 elections for the People’s National Assembly, the National Liberation Front won 220 seats, the National Rally for Democracy won 68 seats and the Islamic parties of the Green Algeria Alliance came third with 48 seats.

The Judiciary

The basic judicial institutions are the tribunals and, at the level of each province, the courts. At the national level, the Supreme Court acts as a supervisor of these local jurisdictions. In 1998 the State Council was created in order to advise the Council of Ministers on the introduction of new legislation. Whenever necessary, the Conflicts Tribunal defines the prerogatives of each institution.

The system is completed by the Criminal and Administrative Tribunals. Separate from the civilian judiciary, the Military Tribunal has jurisdiction over military personnel and organizations.

Legal System

The Algerian legal system is based on European traditions and, to a lesser extent, on Islamic law (Sharia). In colonial times, the French judicial system prevailed, but local courts could still refer to Islamic law in civil and family-law cases. At independence, the National Liberation Front (Front de Libération Nationale, FLN) wanted to reduce the French influence, but found it difficult. Things were further complicated by the reference to both socialism and Islam during the Boumedienne era. Most controversial, however, were the efforts by his successor, President Bendjedid, to introduce a Family Law in which Islamic elements prevailed and the judicial position of women was weakened. In 2005, the law was revised to give women more rights in matters of inheritance and child custody. Judicial reform at the end of the 1980s expanded civic rights, although some of these freedoms were revoked by the security regulations introduced with the state of emergency in 1992.

Judges are appointed by the Minister of Justice. The Algerian system comprises courts at the level of municipalities, courts of appeal located in the capitals of the 48 provinces (wilayat), and the Supreme Court.

Local Government

Algeria consists of 48 provinces, which are divided into 1,541 municipalities. Although executive powers are rather centralized, the provincial governor (wali) is a powerful figure in the Algerian political system. The provincial and municipal councils are elected directly. Local elections were held most recently in November 2012.

After a period of strong centralization during the Boumedienne era, his successor, President Bendjedid, expanded the prerogatives of local government as part of his policy to promote the development of the regions outside the major cities.

Political Parties

Until 1989 Algeria had a single-party system dominated by the National Liberation Front (Front de Libération Nationale, FLN). At the time of Boumedienne’s rule, the small Algerian Communist Party (Parti Communiste Algérien) was allowed to be active, up to a certain point. Shortly after independence, one of the FLN’s historic leaders, Hocine Aït Ahmed, founded the Socialist Forces Front (Front des Forces Socialistes, FFS), which gained legal recognition only in 1989. The sudden liberalization between 1989 and 1991 saw the proliferation of many other political organizations, most importantly the Islamic Salvation Front (Front Islamique du Salut, FIS), which has been banned since it was declared illegal in 1992. With the resumption of parliamentary elections in 1997, many parties were allowed to compete, but this pluralism has not translated into a reallocation of power. The election outcomes are often heavily contested by the opposition, as well as by NGOs and in the media. Formal and informal restrictions make it difficult for parties to wield real power. The opposition therefore struggles repeatedly with the question of whether or not to take part in elections.

The 2012 parliamentary elections resulted in a major victory for the FLN, which, together with the National Democratic Rally (Rassemblement National Démocratique, RND), obtained an absolute majority of seats. The Islamist block scored far lower than predicted, especially by its leadership, while the FFS declared that its 20 seats were in line with expectations. More significant still was the level of participation, as reported by the government, of only 42 percent, with far lower turnouts in the capital. This sign of distrust was compounded by strong protests by the opposition, which accused the government of widespread fraud and manipulation of the elections.

In terms of the number of seats in Parliament, the main political groups are the ‘institutional’ parties FLN and RND. Having originated in the liberation movement, the former state party FLN has always encompassed a variety of ideological currents, regional interests, and personal ambitions.

Throughout recent history – to mention but a few examples – socialist and liberal tendencies competed to succeed Boumedienne; Islamic conservatives within the party won the debate on the Family Law; and overambitious reformers struggled with staunch bureaucrats over how to deal with the bankrupt economy.

This sort of pluralism within a single party has, in a way, continued since the FLN lost its monopoly. This has not prevented it from being a major – often the main – party in Parliament and in the provincial and municipal councils.

The RND was created in 1996 by the then head of state, General Liamine Zéroual, at the time when the FLN-leadership was at odds with the military establishment and even joined the FIS (and the FFS) in a pact aimed at stopping the civil war. Since then, the RND has provided some prime ministers in alternation with the FLN. In general, the party programmes and actual policies of the two parties, which are presently both allied with President Bouteflika, are hard to tell apart.

Islamists

The ban on the FIS in 1992 did not spell the end of Islamist party activism. While the military and political leadership blamed the Front for all the violence that followed the cancellation of the elections at the time, they did not prevent other proponents of political Islam from taking part in formal political life. This has much to do with the huge, often overlooked, differences within the Islamist current that already existed when the FIS came into existence. Some leading Islamists, such as Sheikh Mahfoud Nahnah, strongly opposed the radical populism of the FIS and instead promoted a strategy of gradual Islamization of society. He founded his own party, which later came to be known as the Movement for the Society of Peace (Mouvement de la Société pour la Paix, MSP; formerly called Hamas). Under his successors, the MSP has been a partner in several coalition governments. In 2012 it entered a union with two other Islamist parties, under the banner of the Green Algeria Alliance (Alliance de l’Algérie Verte, green being the colour of Islam).

Another prominent Islamist who emerged on the political scene towards the end of the 1980s is Abdallah Djaballah. He has founded three parties, of which the Islamic Renaissance Movement (Mouvement de la Renaissance Islamique; al-Nahda, or Ennahda, Renaissance, for short) and the Movement for National Reform (Mouvement pour la Réforme Nationale; al-Islah, Reform, for short) continued without their leader and joined the Green Alliance. With a new party, Djaballah took part in the parliamentary election of 2012.

Although the Alliance came third in the 2012 elections and it has been assumed that voting irregularities took place, it is also clear that these Islamist parties are no longer regarded as opposing the political system.

Secularists

The secularist current builds on a long tradition of ideas and organizations within the Algerian national movement. This is particularly true for the various shades of socialist ideas, and, to a lesser extent, liberal ones. Although the socialist tendency within the FLN at times strongly manifested itself, the official ‘Algerian socialism’ was often deemed a vague nationalist amalgam that also included an insistence on Islam as the state religion. It is therefore not surprising that several leftist parties have emerged since 1989. The Workers’ Party (Parti des Travailleurs, PT) is a Trotskyist group and one of the few parties headed by a woman, Louisa Hanoune. The party pleads for social rights and strongly opposes further denationalization and the growing role of multinationals in the Algerian economy.

The FFS has a more social-democratic profile and is the oldest contender with the FLN and the military that ruled in its name. It is the only secular party with a mass base, but this following is limited largely to the party’s stronghold among the Berber population in (or originating from) Kabylia. This also applies to the Rally for Culture and Democracy (Rassemblement pour la Culture et la Démocratie, RCD), whose support is more middle-class in origin and liberal in outlook. The rivalry between the two parties extends beyond their competition for the Berber vote but points to broader questions with which secular parties – in Algeria and elsewhere in the Arab world – are struggling: how to deal with Islamism, and how this affects the relationship with the (military) leadership. In the 1990s the secular parties and civil-society organizations were divided over whether to support the cancellation of elections in order to prevent the FIS from winning. Since the end of the civil war, the FFS and RCD have struggled with their position in a political system that provides them space to manifest themselves but that they regard as hardly democratic.

In 1997 the FFS decided to take part in the first parliamentary elections after the coup, then boycotted elections, before again taking part in elections, in the May 2012 vote. The RCD, a staunchly secularist party, conversely even took part in a coalition government including the Islamist MSP. Both parties also had difficulties connecting with social movements. The uprising in Kabylia in 2001 was largely the doing of local grassroots committees, and in 2011 the RCD’s attempt to capture the mood of the Arab Spring was short-lived.

Foreign Policy

Born of a fierce war against a Western colonial power, it is not surprising that Algeria has sought its international allies mainly among the non-aligned states. In the 1960s and 1970s, it cooperated militarily with the Soviet Union and, as part of the tri-continental movement, supported revolutionary movements elsewhere in the Third World. In the Arab world, Algiers favoured nationalization of the oil industry and the use of an oil boycott against Western supporters of Israel in the 1973 October War. Algeria’s relations with the West have, nevertheless, always been pragmatic. Europe – particularly France, Italy and Spain – is still a main market for oil and gas exports and a source of imports of capital goods and foodstuffs. Economic ties also exist with the United States, but since the 1990s (and especially after 9/11) the emphasis is on military co-operation within the framework of the ‘war on terror’.

History has produced strong ties with the former colonial power. Both France and Algeria find it difficult to acknowledge some of what happened during the war of independence. Meanwhile, a large community of people of Algerian descent have lived in France for decades, as labourers and their children, as former harkis (who fought for France during lebarating Algeria), or as political exiles who fled Algeria during the civil war of the 1990s.

Algeria’s relationships with the neighbouring countries of the Maghreb have long been determined by its rivalry with Morocco. At independence, Morocco claimed part of Algeria and in the 1970s occupied the Western Sahara, whose independence movement POLISARIO is allied with Algiers. This issue remains a bone of contention. The Arab revolutions in Tunisia and Libya were viewed with scepticism and fear by the Algerian establishment. Especially in the Libyan case, Algeria saw an early warning that the chaotic situation would lead to proliferation of arms across the permeable Saharan borders, a fear confirmed in the Mali uprising in 2012 and the attack on the Algerian gas field of In Amenas.

Algeria's Military and the FLN: An Endless and Violent Tug of War

Members of the Algerian Special Forces demonstrate their martial arts skills on July 5, 2017, during a parade organised by the Ministry of Defence marking the 55th anniversary of Algerian independence. Photo AFP

Introduction

Instability defines Algeria as protests continue to sweep the country following the ouster of long-time president Abdelaziz Bouteflika in April 2019 and controversial elections to replace him in December. Historically, the Algerian military, recognized as among the most professional and well-trained in both Africa and the Arab world, has played a dominant role in the country’s politics since independence in 1962, and all governments have been accountable to the military as the locus of power.

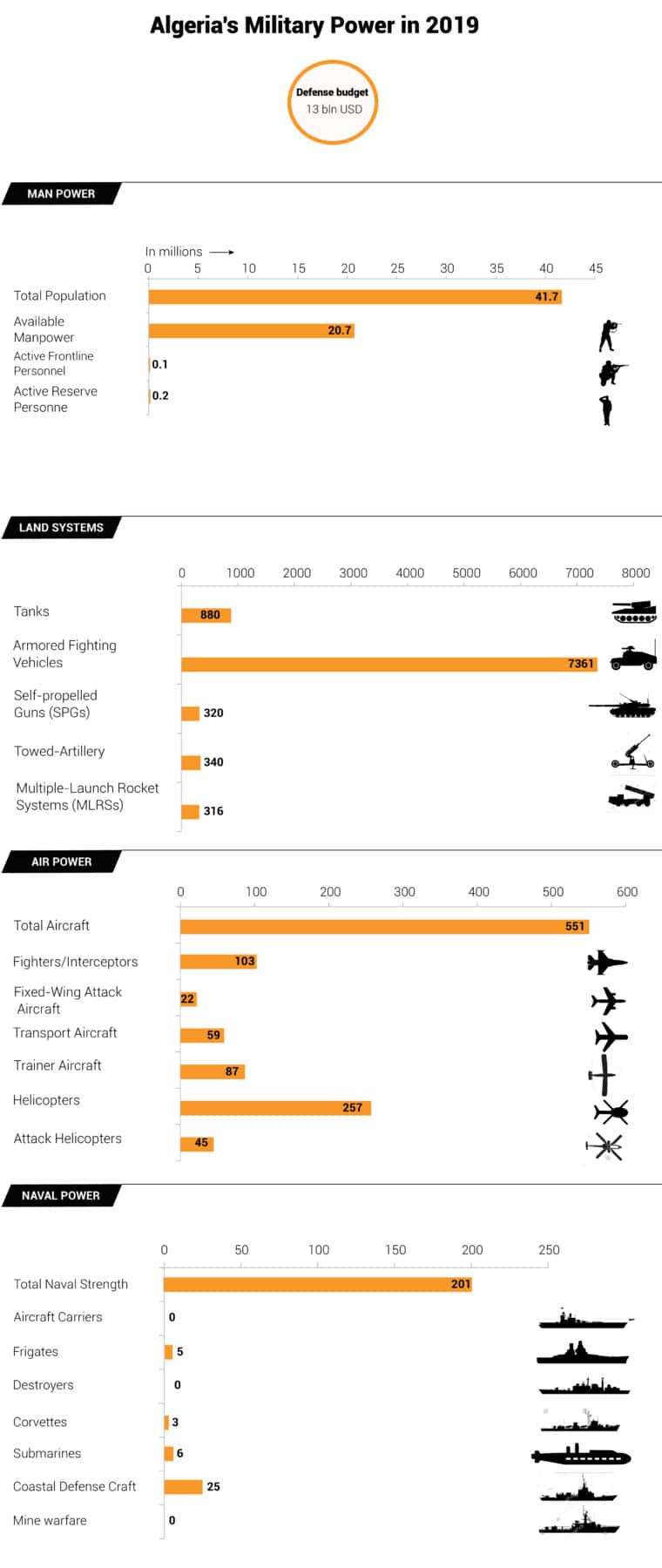

In 2019, Algeria ranked 27 out of 137 countries included in the annual. That year, the number of people who reached military age was estimated at 685,686 personnel, while military expenditure was estimated at $10.67 billion or. In 2018, military expenditure accounted for 5.3 per cent of total GDP, compared with 6 per cent in 2017 and 6.4 per cent in6n 2016, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

| Index | Number | Rank out of 137 |

| Total military personnel | 280,000 | - |

| Active personnel | 130,000 | - |

| Reserve personnel | 150,000 | - |

| Total aircraft strength | 551 | 21 |

| Fighter aircraft | 103 | 22 |

| Attack aircraft | 113 | 24 |

| Transport aircraft | 58 | 13 |

| Total helicopter strength | 284 | 16 |

| Flight trainers | 87 | 31 |

| Combat tanks | 2,475 | 11 |

| Armoured fighting vehicles | 6,900 | 9 |

| Rocket projectors | 367 | 11 |

| Total naval assets | 85 | - |

| Frigates | 5 | - |

Algeria’s military strength in 2019. Source: GFP review:

Algeria’s shadowy ruling elite is largely composed of two highly fragmented factions: the military dominated by the notorious Department of Intelligence and Security (DRS) and the government coalition led by two political parties; the National Democratic Rally (RND) and the former unity party National Liberation Front (FLN) headed by President Abdelaziz Bouteflika. His allies in the state bureaucracy, the military and the FLN are believed to have successfully sidelined the DRS’s long-established leadership after the 2013 In Aménas hostage crisis at a remote gas facility in the Sahara Desert near the Libyan border.

The background of the raid by jihadists, which left at least 38 civilians and 29 militants dead, has never been fully disclosed. However, the hostage crisis and the DRS’s controversial counter-assault on the attackers had immediate repercussions for the ongoing power struggle within the country’s regime and set the course for another dubious shift of leadership which occurred – once again – behind closed doors. Bouteflika’s allies set about stripping the DRS – known during the civil war in the 1990s for its ruthless anti-terror operations – of its authority. However, it remains unclear if this latest shift of power will contain the military’s ambition to play a leading role in Algerian politics.

Algeria’s Bipolar Autocracy

The fragmentation of the regime into a political and military wing has its roots in Algeria’s war of independence in the 1950s. The FNL’s political leaders were either exiled in Cairo or imprisoned in France, while the movement’s armed guerrilla operated inside French Algeria. In 1957, the FLN‘s military wing, the National Liberation Army (ALN), was soundly beaten after a relentless counter-insurgency campaign by the French military, a campaign that also forced the ALN into exile.

In 1960, Colonel Houari Boumédiène took over the ‘border army’, the FLN troops based in Tunisia and Morocco.

Shortly after France announced its complete withdrawal from Algeria, Boumédiène sidelined the FLN‘s exiled leaders in Cairo and formed a strategic alliance with Ahmed Ben Bella, a leading FLN politician.

Immediately after the French pullout in 1962, Ben Bella and Boumédiène’s ALN marched into the capital Algiers and effectively took over control of the newly independent state. Ben Bella became Algeria’s first president and Boumédiène was appointed vice-president and minister of defence. The ALN was subsequently transformed into the country’s military, the People’s National Army (ANP).

During Ben Bella’s presidency, the army evolved into a major political player and gradually expanded its power. This was even before Boumédiène staged a military coup in 1965, ousting Ben Bella and further strengthening the military’s grip on state institutions and the FLN. At the time, Boumédiène had already established an informal power-sharing agreement between the ANP and the FLN, a status quo the regime has largely maintained to this day.

Ever since, the military and the FLN have been trapped in an almost constant tug of war over control of the country’s political agenda and privileged access to the vast oil and gas reserves. As a result, conflicts are common and can turn violent, as the past few decades have shown. To some extent, the regime’s two major wings pursue the same objectives, namely securing privileges and extensive control over oil and gas revenues. Yet in times of declining revenues or power vacuums, the struggle for control increases.

Algerian Civil War

Boumédiène’s death in 1978 created such a power vacuum, paralyzing the country for years. The ANP’s dominant role within the regime was challenged in the 1980s when the massive drop in oil and gas revenues caused a political crisis, followed by a p

opular uprising in 1988. The ensuing democratic transition led to the rise of a radical Islamist party, the Islamic Salvation Front (FIS), and its victory in the first round of the 1991 parliamentary elections. Shortly before the second round of the vote in January 1992, the army staged a military coup, banned the FIS and regained its control over Algeria’s government and the presidency. The radical wing of the FIS went underground and started a guerrilla war against the state.

An estimated 150,000 people were killed during the civil war that followed the 1992 military take-over. The FLN was effectively sidelined by the army leadership while the military became the uncontested leading faction of the regime. This was until Liamine Zéroual, who was appointed president in 1994, paved the way for the return of political parties into Algerian politics. In 1997, his newly established RND party won the parliamentary elections and formed a coalition with the FLN. The restoration of the power-sharing agreement between the army and the regime’s political wing was completed after the military ceased its crackdown and the regime initiated a reconciliation process by supporting the presidential bid of Abdelaziz Bouteflika, Algeria’s exiled former foreign minister and the regime’s ‘consensus candidate’.

Since his election in 1999, Bouteflika has managed to maintain a certain balance of power between the FLN, the RND and the DRS, the military unit that evolved as the state’s most powerful branch after the war. Its ruthless counter-insurgency campaign during the 1990s enabled it to manage and control the conflict while its leader, Mohamed ‘Tewfik’ Mediène, transformed the unit into a major player in Algerian politics.

The ANP’s Modernization

Today, the ANP is one of the most powerful military forces in the Arab world. It has a frontline force of 512,000 and an active reserve of 400,000 and has been pushing to modernize its equipment since 2005.

In the 1960s, Boumédiène had paved the way for the local ALN militias to transform into a centralized national army, gaining strong support from the Soviet Union. Despite Algeria’s nonaligned foreign policy, Algiers has maintained close ties with Moscow. Algerian officers were trained by the KGB, and the ANP was almost exclusively equipped by Soviet arms dealers who remain Algeria’s main providers of military equipment.

Although Algeria’s military has never participated in a major war or intervention on foreign soil – except the short clashes with Morocco in 1963 and 1976 – the regime has sustained the dogma of the necessity of a strong and modern army. In the early 2000s, Bouteflika initiated a comprehensive modernization of the ANP. The rise of Algeria’s oil and gas revenues allowed Bouteflika to expand military spending. In 2005 alone, the budget for weapon purchases was $7.5 billion, having never previously exceeded $100,000 annually. The country has since become Africa’s biggest arms buyer, with an annual budget of over $10 billion. Despite the drop in oil and gas revenues in recent years, Algeria has maintained this high military spending and continues to modernize its army.

Russia remains Algeria’s key military sales partner, supplying SU-30MK fighter jets, T-90S main battle tanks and two kilo-class submarines.

However, the country is currently diversifying its purchases and is buying more equipment from the United States, Italy and Germany. At the same time, it is trying to bolster its own weapons industry, signing contracts with Italy’s Finmeccanica to manufacture AgustaWestland helicopters in Algeria. Similar deals worth up to $10 billion have been signed with Germany.

These include two frigates built by ThyssenKrupp Marine Systems as well as their partial assembly in Algeria, a factory for light wheeled tanks (Fuchs class), built as part of a joint venture with the German companies Rheinmetall and MAN, and a manufacturing plant for Daimler police vehicles. Several German companies also sold electronic equipment such as radio transmitters to Algeria to enable the ANP to tighten control over its southern borders.

The terrorist threat from remnants of the civil war allowed the Algerian military to attract international support for its war on terror, while Tewfik’s DRS successfully used the threat to defend its grip on Algerian politics. When the DRS strongly opposed Bouteflika’s third term in 2009, the tug of war between the unit and Bouteflika’s clan intensified once again.

Who is in charge of ‘le pouvoir’?

After a stroke in March 2013, Bouteflika completely disappeared from public life for several months. His reputation had been seriously damaged during his third term in office, when he was largely seen as a DRS puppet and the civilian face of a de facto military regime. His absence fuelled this narrative, but it did not take long for his clan to strike back.

In September 2013, he announced a major government reshuffle and replaced 18 ministers, including those who had opposed the election of the FLN’s new Secretary General Amar Saïdani the previous month. With this manoeuvre, he regained control over his party and the cabinet and launched a sweeping attack against Tewfik’s DRS.

After appointing the army’s Chief of Staff Ahmed Gaïd Salah as vice minister of defence, Bouteflika scaled back the DRS’s authority by revoking its control over several sub-units and assigning them to the chief of staff, a post now occupied by a Bouteflika ally. The key department affected by this change was the judicial police, a unit responsible for corruption-related investigations, including the 2010 corruption probes connected to the East-West Highway and the state-owned oil and gas company Sonatrach. Tewfik, who strongly opposed Bouteflika’s third term in 2009, is believed to have used the unit to weaken the president, as two of Bouteflika’s key allies in the cabinet were subsequently dismissed on bribery charges linked to the probes. Once again, Bouteflika’s clan hit back.

In August 2015, the military arrested Abdelkader Aït-Ouarab, alias General Hassan, one of Tewfik’s companions and the former head of the DRS’s anti-terrorism department. The retired general, who was involved in the army’s assaults on the In Aménas plant in 2013, was given five years in prison for destroying documents and ignoring orders in a highly publicized military trial. His lawyers presented him as a ‘collateral victim’ in a war of the clans.

Two weeks after Hassan’s arrest, the presidency published a surprising statement, announcing Tewfik’s immediate retirement after 25 years as the country’s head of military intelligence – a political earthquake for le pouvoir (the power), a term Algerians frequently use to refer to the regime.

Tewfik was replaced by his deputy Athmane ‘Bashir’ Tartag, another Bouteflika ally. Shortly after being appointed, Tartag initiated a military purge, fired or retired at least 11 generals and is now the chief of the Directorate of Security Services (DSS), the unit that replaced the DRS in 2016. As the commander of the DRS’s anti-terrorism unit, Tartag was a key figure in the military’s deadly counter-insurgency campaign during the civil war and responsible for the large-scale infiltration of the Armed Islamic Group (GIA), a terrorist organization that systematically executed journalists, artists and foreigners and massacred civilians.

After purging the military, Bouteflika’s clan is believed to have gained extensive control over the deep state, although it remains unclear who spearheaded the campaign, the president himself or Gaïd Salah, who has extended his power base in recent years. Although the regime’s internal power struggle seems to have calmed down for now, the tug of war over Bouteflika’s succession is ongoing.

Latest Articles

Below are the latest articles by acclaimed journalists and academics concerning the topic ‘Politics’ and ‘Algeria’. These articles are posted in this country file or elsewhere on our website: