Introduction

The culture of Algeria has been heavily influenced by the country’s history, in the past and present, whether in literature or music, but rather the arts with all its various forms.

Literary currents have been influenced by French and Arab traditions, and many ethnic groups in the country have contributed to their diverse culture. Algeria was also previously the home of Roman writers, and later other writers such as the theologian Augustine in the 4th century. During the 20th century, Algeria produced several famous novelists, such as Mohammed Dib, Kateb Yacine, and Assia Djebar, whose works were translated on a large scale.

Algerian classical music has its roots in ancient Arab traditions, including Andalusian music. However, today’s most famous Algerian musical genre is Rai, which has pop music flavor and has stars such as Cheb Khaled and Cheb Mami. At the same time, Algerian folk song continues to cast a shadow over the music scene and is very popular with stars such as El Hadj M’Hamed El Anka and Dahmane El Harrachi.

For those with a taste for classical music, Andalusian music, which was brought in by Morisco refugees from Andalusia, is still preserved in many of the ancient coastal cities.

Algeria is also rich with diverse architecture, and this diversity is an important part of the country’s charm and wealth. The cultural wealth was accumulated through the succession of civilizations in this geographical spot throughout history. For example, but not limited to, in many parts of the country we find the Arab-Islamic style embodied in the eastern models of domes and minarets, and in other parts of the city center and other urban places, we find a French heritage manifested in residential, commercial, administrative and other buildings.

Algerian theater emerged during colonial periods, and it was sometimes a platform for indirect criticism of the French rule. After the independence, successive governments supported the establishment of theater troupes and a national theater in the city of Algiers as part of cultural policies, and narrow spaces of freedom provided an opportunity to develop their ideas and prepare the foundations for independent drama, which was also reflected in the development of Algerian cinema.

One of the most famous museums in Algeria is the Bardo National Museum of Prehistory and Ethnography in Algiers. The museum is located in a house built by a French Tunisian businessman in the 19th century, and it houses an important collection of artifacts from the Paleolithic and Neolithic ages, in addition to what is said to be the remains of the Amazigh queen Tin Hinan, whom the Tuareg consider as their spiritual mother.

For more about Algeria’s culture, check what Fanack has covered about this file.

Literature

The literary currents that emerged from the regions of present-day Algeria were influenced by, and actually part of, both Arabic and French traditions. The country was earlier home to Roman writers and to later authors exemplified by the 4th-century theologian Augustine.

A native of French Algeria, Albert Camus set many of his famous works, including L’Étranger (The Stranger) and La peste (The Plague), in colonial society. Isabella Eberhardt travelled in Algeria in the late 19th century, and it left its mark on her novels. She also wrote accounts of her travels and, witnessing armed confrontations between a local leader and French troops, was the first female war-reporter in the country.

Modern Algerian literature begins with the war of independence. Kateb Yacine (1929-1989) wrote his famous novel Nedjma in 1956. One of the founding fathers of modern Algerian literature, he used many historical elements as a means to strengthen Algerian national identity. Unlike many contemporary writers, Kateb Yacine wrote in both Arabic and French but also produced novels and plays in the Algerian Arabic dialect and in Tamazight (Berber). The last years of the French period also saw the rise of Mohammed Dib, who published both novels and poems. Mouloud Feraoun, from Kabylia, is known for his semi-autobiographic novel Le fils du pauvre (Son of the Poor, 1950). The main character, destined by his rural origins to become a herdsman, is driven by a strong desire for a better future. He manages to enrol in school and ends up a teacher. The novel offers a good description of social life and culture in Algeria shortly before independence.

After 1962, the policies of Arabization led to a neglect or even rejection of Tamazight (Berber) cultural expressions as part of official Algerian culture. Many Berber-language writers, most of whom were from Kabylia, also wrote in French. These Tamazight works are mostly oral stories and poems that only recently have been set down in Latin script or, more recently, the Berber Tifinagh script. The entanglement of literature and politics produced remarkable outcomes: in 1980, for instance, the local government in the Kabyle capital of Tizi Ouzou attempted to block a presentation, at a symposium on Berber literature, by the well-known author Mouloud Mammeri. The resulting outrage of the local population was the main trigger for the Berber Spring of that year.

In the following decades, many writers took on social and political issues. The rise of Islamism led Rachid Mimouni to voice his abhorrence of this movement. His novels from the 1980s and 1990s include La malédiction (The Curse), in which he compared Algeria to a ramshackle hospital that would deteriorate further with the coming to power of the Islamist FIS (Islamic Salvation Front, Front Islamique du Salut). Similarly polemical towards political Islam was Tahar Djaout, who paid for his opinions with his life: he was murdered in 1993, probably by radical Islamists. His novel Les chercheurs d’os (The Bone Collectors), however, is about daily life in the aftermath of the war of independence. The title refers to people who travelled the country looking for the remains of relatives who had been killed in the war. Proof of their ‘martyrdom’ would bring their families social recognition and earn them financial compensation from the state.

Music

Algerian classical music belongs to centuries-old Arab traditions, one of which is Andalusian music, harking back to the time when Algeria belonged to Islamic empires stretching across North Africa and southern Iberia. Over the years and especially in the Algiers region, this tradition has developed into the c haabi (popular) style. In the 20th century, this current was revived by the famous M’hamed al-Anka (1907-1978), whose music is still performed. Other traditional styles are the badawi (Bedouin), originating in the desert, and the Egyptian-inspired sharqi (eastern). Strong local musical traditions exist in Kabylia, the Hoggar mountains (near Tamanrasset), and the Saharan town of Timimoun, in the south-west.

Like the rest of the Arab world, Algeria has a tradition of modern classical music performed by famous singers supported by large orchestras. Prominent among them is Warda al-Djazairia (the Algerian Rose), one of the most famous artists of the 1970s. There were influences from elsewhere as well, especially other Mediterranean countries. Raï, the music for which Algeria became famous beginning in the 1980s, emerged as a mixture of Oran nightclub music and modern rhythms. Its popularity derives in part from its lyrics about secret love affairs, wine drinking, and other subjects that were (and still are) unusual or taboo. In the 1980s, this new sound was easily distributed through audiocassettes, which were sold (and often illegally copied) by the hundreds of thousands. The cassette was followed by CDs copied on computers, and DVDs that allowed musicians to add clips of animations to their songs.

As remarkable as its lyrics was the fame that raï acquired on the international music scene. This development went hand in hand with the emergence of raï ‘superstars’ such as Cheb Mami and, especially, Khaled. No longer referred to as cheb (young man), Khaled conquered French concert halls and went far further.

Unfortunately, the Algerian music scene could not escape the violence of the ‘dark decade’ of the 1990s. The raï singer Cheb Hasni, one of those who had refused to move to France, was murdered in his hometown, Oran, in 1994; the explicit lyrics of his songs had infuriated Islamist radicals and authorities. Lounes Matoub, one of the great voices of Kabylia, was kidnapped, triggering mass protests in the region. He was released but then assassinated in 1998. Despite the fact that the GIA (Armed Islamic Group, Groupe Islamique Armé) claimed responsibility for the killing, Matoub’s fans blamed the authorities and set fire to government buildings. Given his openly expressed atheistic worldview and his role as a critic of the government leadership, he had enemies in many places.

Architecture

Algeria’s architecture reflects the country’s history. Along with the remains of Roman times, there is the living example of the Kasbah of Algiers. The old city-centre dates from the 10th century and was later incorporated into an Ottoman construction dominated by a fortress overlooking the Bay of Algiers. In other parts of the city-centre of Algiers and in other urban settings, the French have left a legacy of residences and commercial and administrative buildings. The main post office of Algiers, built in the 1930s and still in use, is an example of a neo-oriental building with elaborate stylistic elements.

The destruction brought by the war of independence and the economic development following it prompted ambitious government building initiatives. Commemorating those who fought for the creation of an independent state, the Martyr’s Monument is exemplary of modern Algiers. It consists of three palm leaves forming a tower, alongside the war museum and a modern shopping centre, Riad al-Fath. Another major project is the new Great Mosque of Algiers, scheduled to be completed in 2015. Rivalling the Hassan II Mosque in Casablanca, Morocco, the complex on the capital’s sea-front has a capacity of 120,000 worshippers and is marked by a 265-metre minaret. After many years of planning, construction (by a Chinese company) began in the spring of 2012.

Theatre and Film

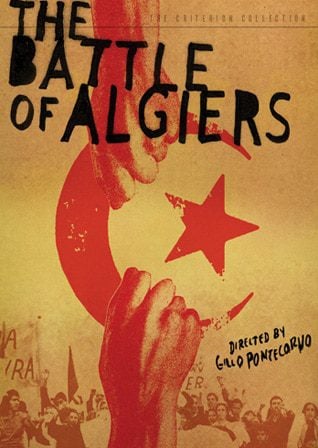

The Algerian film industry is well developed and sometimes reaches viewers abroad. This results, in part, from the state’s efforts to promote the image of independent Algeria. Following the war of independence, filmmakers were given free rein for movies about the fight against French colonialism. The pre-eminent example of this genre is The Battle of Algiers (1966), an epic account of the struggle between urban guerrillas of the National Liberation Front (Front de Libération Nationale, FLN) and the French army. The Italian-Algerian co-production gives a realistic account of the harsh realities of the war and the characters of its protagonists. It paints a bleak picture of the French ‘civilizng mission’ imposed by executions and torture, but it also depicts conflict within the FLN and bomb attacks on civilian targets. In the end, the Algerian people appear as the true heroes.

More recent films treat themes of contemporary society. Omar Gatlao, by Merzak Allouache, is about the empty lives of young men hanging around in the cities, unemployed and frustrated by the impossibility of marriage. Allouache also treated the rise of Islamism (Bab al-Oued City) and the relationship between Algerians and their relatives who migrated to France (Salut cousin!).

His most recent production, Le repenti (2012) is about the aftermath and unfinished history of the civil war of the 1990s: a member of an Islamist group is pardoned and reintegrated into society, but he and the other protagonists ultimately prove unable to escape the consequences of their past deeds.

Of a lighter tone is Mascarades (2008) by Lyes Salem, about intrigues in a small village centring on the difficulties of tradition, family life, and relations between the sexes.

Theatre emerged in colonial times and sometimes served as a platform for indirect criticism of French rule. After 1962, the Ministry of Culture sponsored the creation of theatre groups and a national theatre in Algiers, as part of the government’s cultural policies of ‘rediscovering’ Algerian national traditions. In order to escape the state’s watchful eye and to find room for more critical views of past and present Algerian society, many actors and playwrights preferred to produce their own plays. The liberalization of 1989 provided them the opportunity to develop their ideas and lay the foundations of independent drama. Their hopes were short-lived: in the ‘black decade’ of the 1990s, critical voices were silenced, sometimes by murder. The famous playwright Abdelkader Alloula was one of the victims of targeted killings by Islamist armed groups.

Museums

One of Algeria’s most famous museums is the Musée National de Préhistoire et d’Ethnographie du Bardo in Algiers. Located in a house built by a French-Tunisian businessman in the 19th century, it contains an important palaeolithic and neolithic collection, as well as what are said to be the remains of the ancient Berber queen Tin Hinan, whom the Tuareg regard as their ancestor. The war museum attached to the Martyrs’ Monument in Algiers exhibits the history of the war of independence. The capital is also home to the Modern Arts Museum, as well as museums of antiquities, fine arts, and traditional culture. Many provincial towns have their own museums, dedicated to natural history, local culture, and the war of independence. The civil-war museum in Oran is named for local war hero Ahmed Zabana, the first independence fighter to be executed by the French, in 1956. Remote towns, such as Djanet in the far south-east, have geological or archaeological museums specializing in local excavations and finds. The Archaeological Museum of Cherchell is famous for its Greek and Roman collections. This region, which also includes the Roman excavations at Tipaza, has many other remains from ancient times, as well as some from the Byzantine era.

Sports

Football is by far the most popular sport in Algeria. Every city has at least one club, and the teams compete in several leagues. There is also a national women’s competition. Competition is dominated by the leading teams from the big cities, including the principal suburbs of Algiers, some of the latter dating back to colonial times. Sports became intermingled with politics during the rise of Algerian nationalism and, in particular, during the war of independence. On the eve of the world championship in 1958, the seven Algerian members of the French national team shocked the football world: two months before the beginning of the championship tournament, they left the team, depriving France of its best players, and travelled to Tunis to join the FLN team (National Liberation Front, Front de Libération Nationale). This angered the French, who took steps to exclude the nation-to-be from international competition. The FLN team, however, had ample opportunity to play at the international level, as many Arab, non-aligned, and communist countries were happy to invite them to play. Remarkably, some of the best players had no problem returning to their original French clubs once the war had ended.

The national team is nowadays generally one of the principal contenders for the Africa Cup. Success in World Cup tournaments is less common, but Algerian football fans are still aware that they managed once, in 1982, to beat the champion-to-be, West Germany. The Algerian national team participated in the FIFA World Cup four times in 1982, 1986, 2010 and 2014. It has also participated 18 times in the African Nations Cup and won the title in 1990 and 2019. In October 2020, Algerian’s national football team ranked 31 in FIFA’s world ranking table.

The national competition attracts huge numbers of supporters to the stadiums of their favourite clubs. At times this leads to clashes among groups of fans, especially at decisive games at the end of the season, but the occasional riots may be regarded also as a symptom of more general social tensions. When the FLN was still the only political party, the games were one of the few occasions on which people could voice their discontent. Algeria has also achieved some standing in other international sports, especially track, boxing, and athletics. The middle-distance runner Hassiba Boulmerka, for example, won several gold medals in the 1990s, including one in the 1,500 metres at the 1992 Olympic Games in Barcelona. She received death threats during the civil war and was forced to move abroad.

Latest Articles

Below are the latest articles by acclaimed journalists and academics concerning the topic ‘Culture’ and ‘Algeria’. These articles are posted in this country file or elsewhere on our website: