Introduction

Egyptian culture can be described as a melting pot of a series of different cultures and traditions, rooted in the depths of six thousand years of recorded history. It is the product of one of the most ancient human civilizations (Ancient Egypt Civilization).

Since the end of the Pharaonic era, Egypt has fallen under a series of successive occupations, and these occupations exchanged influence and interaction with Egypt’s ancient culture, to become more rich and diversified.

However, Egypt’s culture has been influenced by many cultures, to produce a distinctive mixture, in which those cultural aspects of ancient Egypt have merged with all subsequent cultures, and ultimately constituted the features of the contemporary Egyptian culture in its current form. A culture that manifested itself with the ideal fusion of different cultures.

On the literary level, contemporary literature is an important cultural element in Egyptian life. Egyptian novelists and poets were among the first to experiment with modern methods in Arabic literature, and the forms they developed were widely imitated throughout the Middle East. Therefore, Egypt is considered the cradle of modern Arabic literature, and it includes many publishing houses, some of which were established more than 100 years ago.

Egypt also has a long tradition of belly dancing. It is believed that its origin is the fertility dance that priestesses used to perform in Pharaonic times, and it still exists to this day in two main forms: the Baladi dance, and it is performed by women at wedding parties; And belly dance, performed by professional dancers.

The beginnings of contemporary Egyptian music can be traced back to the creative works of people such as Abdo al-Hamuli, Almaz, and Mahmoud Othman, who influenced the later works of the pillars of Egyptian singing such as Sayed Darwish, Umm Kulthum, Mohamed Abdel Wahab, and Abdel Halim Hafez.

The Egyptian film industry is often called the “Hollywood of the Arab world” or “the Hollywood of the East.” Film historians consider the middle of 1907 as the beginning of history for Egyptian cinematic production when at that time Aziz and Doris’ company in Alexandria filmed the Khedive’s visit to the High Institute in the Sidi Abu al-Abbas Mosque and displayed it in the Motion Pictures Gallery.

But Egyptian cinema was truly born in 1923 when Mohamed Bayoumi (1894-1963) returned from studying cinema in Germany and filmed the first Egyptian movie “The Land of Tutankhamen”. Hundreds of documentary and feature films were produced, they are truly a history of this important period in Egypt’s history, which witnessed its transformation from monarchy to republican rule more than half a century ago.

For more about Egypt’s culture, check what Fanack has covered about this file.

Dance

Folkloric dance in Egypt is divided regionally into the dance from the Delta (fellahi), the Upper Delta (Saidi), the coastal area (Sawahili), Sinai (Bedouin), and the Nubian area. These dances not only survive locally but are also preserved by the Reda Group for Folkloric Dance, which was established by Mahmoud Reda and Farida Fahmy in the 1960s, and the National Troupe for Folkloric Arts, which performs these dances nationally and internationally.

Egypt also has a longstanding tradition of belly dancing. Believed to have originated as a fertility dance performed by priestesses in Pharaonic times, it exists today in two main forms, as a folk dance (raqs baladi), performed by women at parties and weddings, and as a form of entertainment by professional dancers (raqs sharqi).

With the advent of cinema, in the early 20th century, the film industry made icons of belly dancers. The late Tahiya Karioka and Samia Gamal and the now retired Soheir Zaki and Nagwa Fouad are probably the most celebrated belly dancers of Egypt. Other more recently famous belly dancers are Fifi Abdou and Lucy, both now retired as well. The ruling queen of Egyptian belly dance is Dina Talaat.

Professional belly dancers are often hired to perform at weddings, but given the current wave of Muslim conservatism, it is no longer in vogue and is considered sinful by many. Many dancers are now relegated to sleazy nightclubs. Indeed, the profession is associated with prostitution, sometimes correctly. Alternatively, many belly dancers find employment performing for tourists.

Another traditional form of dance is the Sufi dance of the whirling dervishes. It is performed at Sufi gatherings and shows and has become a form of entertainment in tourist spots.

Egypt also has a national ballet, the Cairo Opera Ballet, which was established in 1966 and is associated with the Higher Ballet Institute (Academy of Arts). Initially coached by Soviet trainers, the Egyptian Ballet began performing abroad in 1973. In addition to the classics of ballet, it performs pieces by Egyptian composers and choreographers.

The development of contemporary and experimental dance in Egypt was long crippled by lack of funding and continuing-education programs and the limited accessibility of rehearsal and performance spaces. An additional problem lay in government interference that resulted in the monopolization of many fields of the arts by a single person or organization.

For example, Lebanese theatre director Walid Aouni, founder and director of the Cairo Opera House Modern Dance Theatre Group, for a long time reigned supreme in the world of modern dance. He was the artistic director of the Opera House’s Modern Dance Academy, the Modern Dance Company, The Festival of Modern Dance Theatre, and his own company, ‘Knights of the Orient’.

Since the January revolution, the many independent theaters of Cairo, such as Rawabet Theatre, al-Sawy Culture Wheel, Falaki Theatre, and Darb 1718, freed of government interference, have provided space and opportunity for ground-breaking modern-dance performances.

Literature

Egypt is the birthplace of modern Arabic literature and boasts numerous publishing houses, some of them more than a hundred years old, such as Dar al-Hilal, Dar al-Bustani, and Dar al-Maarif. This is the home of such great authors as Tawfiq al-Hakim (1898-1987), who developed Arabic drama; Taha Hussein (1889-1973), nicknamed the Dean of Arabic literature; Yusuf Idris (1927-1991), who is considered to be the master of the Arabic short story; and Naguib Mahfouz (1911-2006), the only Arab novelist to win the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Written in styles that vary from the naturalistic, historical, romantic, and social realist to the magical realist, politically engaged, individualist, and graphic novels, books are everywhere in Egypt. Cairo is bustling with famous bookshops, such as Madbouli and al-Shorouk, libraries, and book stands on the streets. Annually, the country hosts one of the largest book fairs of the Arab world, the Cairo Book Fair, and has one of the oldest second-hand book markets, Sur al-Azbakeya.

Literature is, however, handicapped by several factors, including the high illiteracy rate and censorship by the Ministry of Culture and the religious institution of al-Azhar. Much has been done to reverse the decline in reading, from programmes to combat illiteracy to one of the few projects of good repute undertaken by Egypt’s former first lady, Suzanne Mubarak, the Reading-for-All Campaign. The establishment of independent publishing houses that are willing to take more risks, and the spread of the Internet, which has given a voice to many, help maintain Egypt’s reputation as the leader in literary development in the Arab world.

Naguib Mahfouz

Naguib Mahfouz (1911-2006) was the first (and so far the only) Arabic-language writer to win the Nobel Prize in Literature, in 1988. During his career of seventy years, he published 34 novels, over 350 short stories, dozens of movie scripts, and five plays. His works have been translated into more than forty languages. Many of them have been made into successful films in Egypt, and several have been adapted into film in Mexico.

Mahfouz was influenced by a wide variety of literary styles, both Arab and Western. For inspiration he read Western detective stories, Russian classics, and modernist works of Proust, Kafka, and Joyce. Mahfouz tried his pen at many styles, starting with historical novels such as The Struggle of Thebes (1944) and moving in the 1950s to naturalistic novels, of which The Cairo Trilogy was the most important.

In the three novels Palace Walk, Palace of Desire, and Sugar Street, set in the neighbourhood where he grew up, Mahfouz depicted the life of a family over three generations, from the early 20th century to the 1950s, when King Farouk was overthrown. In the 1960s he got into critical realism, with such novels as The Thief and the Dogs (1961), Quail and Autumn (1962), and Miramar (1967). He also published several novels in the symbolist style, the best known of which is Children of Gebelawi, also called Children of Our Alley.

Mahfouz originally published this novel in 1959, but it was banned until 2006 for its allegorical portrayal of God and the three monotheistic faiths, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. He continued to publish, in various styles, until his death.

For some years, his books were banned in many Arab countries in response to his outspoken support for Sadat’s efforts to reach a peace agreement with Israel. Mahfouz was threatened by Islamic extremists for his novel Children of Our Alley, which was considered blasphemous and was banned by al-Azhar.

Matters got worse when he publicly condemned the Iranian death-fatwa against the British author Salman Rushdie, even though he found The Satanic Verses to be insulting to Islam. In 1994, at the age of 82, he was attacked and stabbed in the neck outside his house in Cairo. Mahfouz suffered severe nerve damage to his right hand, making writing extremely difficult. The young extremist who attempted to assassinate Mahfouz was sentenced to death and executed.

Alaa al-Aswany

The new literary star on the Egyptian scene is dentist-turned-writer Alaa al-Aswany (born 1957). After writing columns in Egyptian newspapers on literature, politics, and social issues, co-founding the Kefaya movement for change prior to the January Revolution, al-Aswany tried his hand at novel writing.

His second novel, The Yacoubian Building, was an instant hit and was so widely read in Egypt and the rest of the Arab world that al-Aswany is the first Arab author to have sold more than one million copies of a single book. His success grew after the novel was translated into 31 languages. In 2006, the book was adapted into a successful film (2006) and a television series (2007).

In January 2007, al-Aswany published Chicago, a novel about the Egyptian community in the American city where he himself was trained as a dentist. Since the revolution, al-Aswany has focused more on political analysis and activism.

Egypt also has several notable female writers, including the strident feminist activist Nawal al-Saadawi (born 1931), short-story writer Alifa Rifaat (1930-1996), and Miral al-Tahawy (1968), who won the Naguib Mahfouz Medal for Literature. The American University in Cairo Press makes great efforts to translate literary works of Egyptian authors into English.

Film

The Egyptian film industry is often called the Hollywood of the Arab world. Egyptian cinema was born in 1923, when Mohammed Bayoumi (1894-1963) returned from studying cinema in Germany and shot the first Egyptian movie, In the Land of Tutankhamun.

From then until the 1960s, Egyptian cinema dominated screens across the Arab world, spreading Egyptian culture, music, and the Egyptian dialect throughout the region. Studios in Cairo turned out more than a hundred films a year during the 1940s and 1950s, a period considered the golden age of Egyptian cinema.

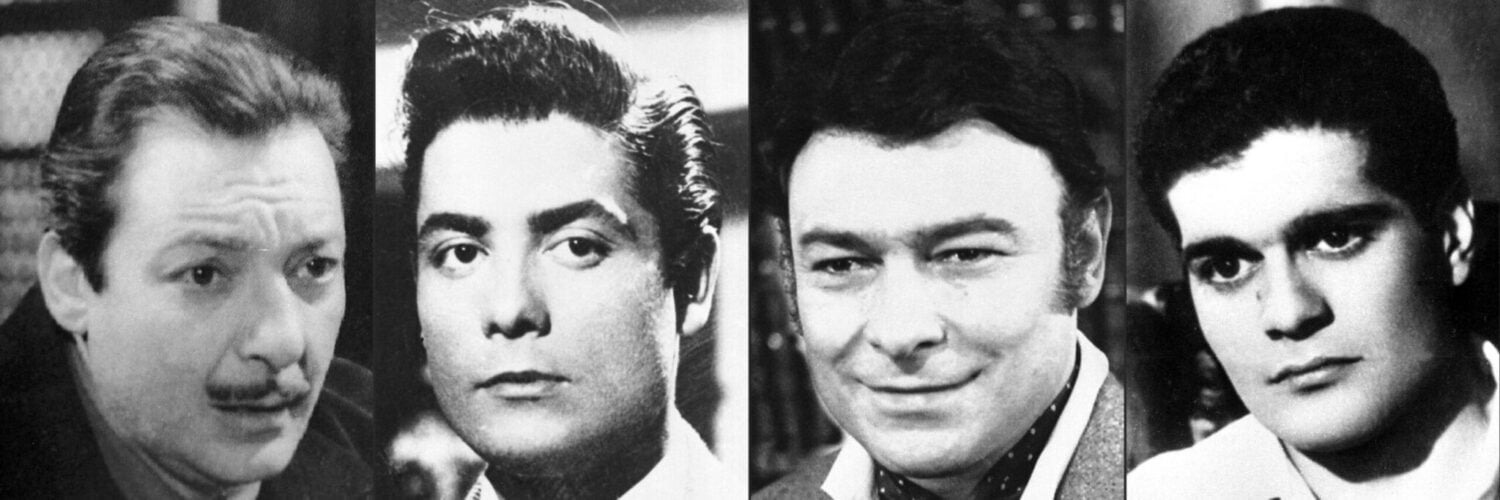

Among the great male stars of the classic movies are Rushdy Abaza (1926-1980), Shukri Sarhan (1925-1997), and Omar Sharif (born 1932), who shot to worldwide fame when he played the main role in the Hollywood production Dr. Zhivago. Female stars include Faten Hamama (born 1931), Nadia Lotfi (born 1938), and, doubtless the most famous, Soad Hosny (1943-2001).

The quality of Egyptian films declined after the 1970s. In the 1970s, Egyptian cinema began to produce films specifically for the Gulf, offering a mixture of sex, drugs, and violence. The 1980s witnessed the rise of movies revolving around one star, mainly the actresses Nabila Ebeid (born 1945) and Nadia al-Gondi (born 1950) and the actor Adel Imam (born 1940), who is considered today the most famous Egyptian actor. Other movie stars include Ahmed Zaki (1949-2005), Mahmoud Abdel Aziz (born 1946), and Yousra (born 1955).

By the late 1990s, a new wave of young Egyptian actors and actresses dominated the screen, producing what are known as shababi (youth) movies. Most of them were mediocre comedies. The phenomenon of ‘contractor movies’, which were meant only to fill the cinemas with cheap and uncomplicated entertainment, did little to help. If fact, comedy and slapstick slowly became staples of the Egyptian cinema.

With the increasing number of satellite Egyptian and Arab entertainment channels, however, there was a greater demand for Egyptian movies, reviving the industry and allowing the emergence of a few promising actors and directors. During the last years of Mubarak’s rule, a number of more daring films were produced, such as the politically critical Imarat Yacoubian (The Yacoubian Building) in 2007 and Heya Fawda? (Is It Chaos?) by the notable directors Youssef Chahine (1926-2008) and his protégé Khaled Youssef (born 1965) in 2008. Mohammed Diab’s 678 and Mohammed Amin’s Binteen fi Masr (Two Girls in Egypt) both came out in 2010 and were highly critical of women’s issues, the first one dealing with sexual harassment and the second with the life and problems of the average single Egyptian woman.

Since the revolution, Egyptian cinema has collapsed completely, due on the one hand, to the economic situation – with poverty on the rise, buying a cinema ticket has become difficult – and on the other hand, to the old formula of mindless comedy, which is less and less appealing to people who expected the Egyptian cinema industry to be more involved in current issues, and most films still star the same celebrities, some of whom gained bad reputations for their support of Mubarak.

Soap Opera

The export of Egyptian soap operas across the Arab-speaking region has spread contemporary Egyptian culture and language perhaps more even than Egyptian cinema has done. The production of television-series for the holy month of fasting, Ramadan, has proven especially lucrative for the industry. During Ramadan, Muslim families throughout the Middle East typically spend their evenings and nights enjoying food and television programmes, mostly made in Egypt.

Since the revolution, the production of soap operas has increased greatly. It reached its peak in 2012, with an extraordinary seventy different series being aired around the Arab world. The series produced since 2011 differ greatly from earlier ones.

In 2011, al-Muwatin X (Citizen X) came out, a highly critical series that was based loosely on the life of Khalid Saeed, a youth who was beaten to death by the police in Alexandria in 2010. Ramadan 2012 featured the series Taraf Talet (A Third Party), which was critical of many apparently conspiratorial aspects of the most recent rule of the country.

Most series featured many new young faces, even though in 2012 several major stars, inclding Adel Imam and Yousra, took a stab at series. These soap operas were different also in terms of language, with cursing never heard before, particularly during the holy month of Ramadan.

Food

Egyptian cooking is relatively simple but tasty. Many dishes are similar to the food found throughout the eastern Mediterranean and the Middle East.

Bread

Bread is, without a doubt, the most important item of the Egyptian diet; it is eaten with almost all meals. No wonder there is one colloquial Egyptian Arabic word, eish, for both ‘bread’ and ‘life’. Millions of people get their daily ration of bread from government-subsidized bakeries. The round flat breads are distributed through a barred window for 25 to 50 piasters each, less than USD 0.01.

Cheese

A native cheese called gibnehis used mostly for sandwiches and comes in two varieties, gibneh beida, a soft white cheese of variable saltiness, and gibneh Rumi, a sharp, hard, yellow cheese.

Vegetables

As the price of meat and chicken has risen steadily in recent years, many Egyptians eat mainly vegetables. Fortunately, the Nile Delta provides the country with fresh, juicy, and tasty vegetables all year round. Vegetables such as okra, beans, and various types of squash, are typically cooked in a thick tomato sauce. Popular Egyptian dishes include ful medames (mashed fava beans, often eaten for breakfast), molokheya (a green soup made from the finely chopped mallow leaves, garlic, and coriander), and kushari (brown lentils, macaroni, rice, chickpeas, and a spicy tomato sauce).

Another famous dish is mahshi, made with vegetables such as grape leaves, cabbage leaves, green peppers, aubergines, courgettes, and tomatoes that are stuffed with spicy rice mixed with fresh green herbs, such as coriander, parsley, and dill, and rarely mixed with minced meat. Falafel, or tameeya, is available on every street corner.

Meat, poultry, fish

Beef, lamb, buffalo, and goat meat is prepared in various ways. Skewered and grilled on charcoal, either in chunks (kebab) or minced and rolled (kofta); shredded (shawerma) and stuffed into baladi bread (large, flat, rounded, pita-like bread) with tomatoes, pickled vegetables, and tahini sauce; or slow cooked in a vegetable stew.

Because chicken is cheaper than other meats, much more of it is consumed, grilled, cooked, fried, or as shoarma.

Most Egyptians also enjoy fish and shellfish, which comes from the Mediterranean, the Red Sea, the Nile, and Lake Nasser.

Desserts

Egyptian desserts really cannot be too sweet. Pastries and puddings are usually drenched in sugar syrup. Among the pastries is baklava (filo dough, honey, and nuts), atayef (small dumplings stuffed with cream or nuts), konafa (a pastry made of thin strings of dough stuffed with white cheese), fateer (pancakes stuffed with anything from eggs to apricots), and, one of the most popular, basbousa (semolina pastry soaked in sugar syrup and topped with nuts).

Puddings include ruz bi-laban (rice pudding), mehalabeya (corn-starch pudding), bileela (a hot-milk pudding with whole wheat, often eaten for breakfast), ashura (a wheat pudding with nuts, raisins, and rose water that is eaten on the holy day of Ashura), and Umm Ali (a pudding made of thin pastry, nuts, and raisins soaked in milk).

Coffee and tea

Not simply a place to go for a beverage, coffee houses play an important role in Egyptian society. It is mainly men who frequent coffee houses to meet and relax with their friends, leaving the home to the women. People also run their businesses from coffee houses: Many independent plumbers, carpenters, and other professionals will be at the coffee house, where they can be reached by customers. Business deals will be closed, agreements made, and disagreements settled.

Even the foreign coffee chains, such as the American Starbucks and the British Costa Coffee, serve the same purposes and also provide women an opportunity to run their businesses. As they offer Wi-Fi, these foreign chains also tend to attract a more diverse clientele.

Despite these newcomers, traditional coffee and tea houses are still as plentiful as they are crowded. Here, Turkish coffee and strong tea are the prevalent drinks. Turkish coffee is made by boiling a mixture of very finely ground Arabica coffee beans, water, sugar, and sometimes cardamom seeds. When ordering a cup, one states the amount of sugar desired: ziyada (very sweet), mazbut (just right), ariha (very slightly sweetened), or sada (black).

While tastes in coffee vary, most Egyptians prefer their tea as sweet as possible. A cup of shai is offered in almost any situation and should not be declined. This often means just a glass of hot water with a Lipton teabag in it, but a true shai is a strong brew made from boiling water and local tea leaves together in the kettle.

Sports

Football is by far the leading sport in Egypt. The two clubs from Cairo, al-Ahly (also known as the Red Devils) and al-Zamalek (the White Devils), traditionally compete for the championship in the national league, with the former winning the top spot in the last seven consecutive years (since 2005).

Egypt’s national team has had some international success, especially in the Africa Cup of Nations, which it has won six times, most recently in 2006 and 2008. T he national team has only qualified for the FIFA World Cup three times, the most recent in Russia 2018 In October 2020, Egyptian’s national football team ranked 52 in FIFA’s world ranking table.

Handball is the second most popular sport. In 2008, the national team won the African Handball Nations Championship for the fifth time.

Egypt has had only limited success on the international level. In all the Summer Olympic Games since 1912 Egypt has won only seven gold, seven silver, and nine bronze medals, mostly for weightlifting and wrestling.

The Egyptian Amr Shabana is arguably the world’s best squash player. He won the World Open three times (2003, 2005, and 2007) and was ranked number one in the world in 2006 and 2008.

In the 2012 Olympics, Egyptians won two silver medals, Alaaeldin Abouelkassem in fencing and Karam Gaber in wrestling.

Latest Articles

Below are the latest articles by acclaimed journalists and academics concerning the topic ‘Culture’ and ‘Egypt’. These articles are posted in this country file or elsewhere on our website: