Introduction

Syrian culture was not excluded from the crisis of asylum and diaspora that Syrians are still going through since the outbreak of the crisis in the country in March 2011. The Syrian culture also migrated via other means, including jumping on dangerous fishing boats as a massive number of Syrians did, and thus a significant aspect of their culture crossed the boundaries of space to nowhere far from its cradle, where there are no barrels bombs, no black flags, and no hordes of warring armies. And so, the ties of a civilization and a culture as ancient as human history were severed, just like those of Syrian families were severed in escape from violence.

To where papers, pens, inks, and colors can find a calm and safe haven that allow creative thoughts to flow over the Arab and international cultural scene again, most of the country’s creators, famous writers and fine artists at the Arab and perhaps international levels moved, as well as Syrians working in music, theater, and cinema who have influenced the Arab cultural life for decades, those who cannot be enumerated by our lines.

Syria’s cultural heritage has also been exposed over the first decade of the crisis to dangers and cases of looting, theft, and illegal trafficking of cultural property without being seen or solved. Also, significant archaeological sites and monuments have been destroyed or severely damaged, according to UNESCO.

The Syrian cuisine, and its unique dishes, became famous throughout the diaspora, and the Arab drama funded by the Arab Gulf was invigorated by the works of Syrian artists. The Syrian culture wrote new cultural pages with the flavor of current events in their country.

Internally, and despite the destruction of more than 70% of the cultural centers due to being located in hot spots, it was remarkable that the number of theatrical and cinematic works increased dramatically compared to what was produced before 2011, according to studies.

Pure Syrian artistic participation was indeed absent from cultural events in the region, as a result of Syrian President Bashar Al-Assad’s isolation from the Arab world, and thus seminars, events, and festivals pass in the Arab world culture skies and around the world without Syrian participation, except the individual participation of those who live outside the country’s walls, and those who do not represent the Syrian culture and all its various and diverse aspects. Besides, prominent names of creative people, both supporters and opposers to the Syrian regime, fade from the world of intellect and culture.

Syria has a rich cultural life. Damascus and Aleppo been cultural centers for centuries, and today, the arts are still very much alive in these cities. Museums may be somewhat run down, but there are many art galleries showing contemporary art. Music – traditional as well as modern, and Arab as well as Western – plays an important part in Syrian culture.

Almost every city has its own music and/or dance festival, and so do important archaeological sites (Palmyra, Bosra). Film and theatre are very popular and subsidized – despite subsidized films frequently being banned. Television soap series (Syrian and foreign) are also immensely popular.

To learn more about the culture of Syria with all its diverse aspects, check what Fanack has covered in this file.

Crafts

In the past, Aleppo and Damascus were on the Silk Road. Silk is still sold in the souks, and silk and other garments are still made in small factories and homes, as is embroidery, although in family settings and not on a large scale. Two other main crafts are still practiced in Syria: jewelry making from silver and gold and marquetry.

Literature

As one of the centres of Arabic culture, Syria has made an important contribution to medieval Arabic literature. It has produced many writers, including the highly influential poet Abu Tammam, the poet, philosopher and prose writer Abu al-Ala al-Maarri, and the all-round scholar Bar Hebraeus or Ibn al-Ibri.

The history of the country was narrated by Aleppin and Damascene chroniclers. For instance, much of what is known about the Crusades is derived from the writings of chroniclers such as Ibn al-Qalanisi (ca. 1073-1160), the Persian Imad al-Din al-Isfahani (1125-1201), Baha al-Din ibn Shaddad (born in Mosul, 1145-1234), Kurdish Ibn al-Athir (1160-1233), and Abu Shama (1203-1267).

An exceptional figure was Emir Usama ibn Munqidh (1095-1188), both an ambassador and a writer, who knew Nureddin, Saladin and many other rulers personally. The 11th century Syrian philosopher, poet and writer Abu al-Ala al-Maarri propounded remarkably sceptical views of religion, rejecting dogmatism and the monopoly of truth in religion.

Abu Tammam

Born in Damascus as the son of a Christian innkeeper, Abu Tammam (circa 805-circa 845) converted to Islam, changed his name and invented a fictitious Arab genealogy for himself. He worked in Damascus as a weaver and in Cairo as a water seller, but soon began to study poetry. His reputation was established after he found favour with caliph al-Mutaṣim. This enabled him to travel, and on his return from Iran he began compiling his main work, the Hamasa (Exhortation). This collection of poems deals with contemporary events of historical significance. While his command and purity of language are generally recognized, his excessive use of poetical devices is not appreciated by all critics.

Al-Maarri

This highly original, pessimistic, blind poet, who was suspected of heresy more than once, spent almost his whole life in a village south of Aleppo, Maarrat al-Numan. In 1008, three years after the death of his father, al-Maarri (973-1058) went to Baghdad. However, despite his phenomenal memory, erudition and skills, he failed to earn a decent living there. He returned to his hometown, a bitter man for the rest of his life.

Saqt al-Zand (Spark from the Fire-stick, a collection of his early poems) and Luzum ma la yalzam (Self-Composed Compulsion, later work) are al-Maarri’s best known poetry works. The Risalat al-Ghufran (The Epistle of Forgiveness, an ironical prose vision of life in Paradise) is one of his most important works. Al-Maarri was known for his skepticism of religion.

Bar Hebraeus

Bar Hebraeus (1226-1286) was born in Armenia as Abu al-Faraj ibn Harun al-Malati. His father, a Jewish convert to Christianity, urged him to pursue a scholarly career. Abu al-Faraj studied medicine with his father and rhetoric and theology in Antakya (Antioch) and Tripoli. Although he was consecrated bishop when he was twenty years old, his episcopal duties did not keep him from compiling, rearranging and translating collections of classical philosophical and theological Arabic texts. He also wrote treatises on grammar, astronomy, mathematics, medicine, philosophy, theology and history.

Among his chief works is an encyclopedia of philosophy, Ḥewath ḥekhmetha (The Cream of Wisdom), in which he commented, in the Aristotelian tradition, on every branch of human knowledge. He wrote mostly in Syriac, but also in Arabic, the lingua franca of the time. The variety, extent and erudition of his writings are remarkable. Moreover, Bar Hebraeus’ political and religious tact enhanced the cultural exchange between the Christian and Muslim worlds.

Adab

Adab, meaning ‘literature’ in Arabic, encompasses more than belles-lettres as it is understood in the West. One of the disciplines of Adab is historiography. Several Syrian chroniclers are worth mentioning. The Damascene teacher and philologist Abu Shama (1203-1267) wrote the Kitab al-rawdatayn (Book of the Two Gardens, a compilation of earlier Islamic sources on the Crusades interspersed with his own remarks). Dhayl Tarikh Dimashq (Supplement on the History of Damascus) by Ibn al-Qalanisi (1070-1160), a politician and son of a well-known Damascene family, is an account of the First Crusade from a Muslim perspective, and therefore an important source for historians.

Usama ibn Munqidh (1095-1188), a poet of noble descent, has written several anthologies. Nowadays he is best known for his Kitab al-Itibar (translated in English as The Book of Contemplation). From a literary point of view this autobiographical book is clearly the most interesting of the three. His description of the crusaders (with whom he had had frequent encounters on and off the battlefield) as villainous and utterly stupid, is vivid and amusing.

Another chronicler, Ibn Kathir (1300-1373, born in Bosra), was one of the best-known historians and traditionists of Syria under the (Bahri) Mamluks. At the end of his life he was awarded a professorship in Koranic exegesis at the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus. He wrote one of the principal works on the history of the Mamluk period, al-Bidaya wa-al-Nihaya (Beginning and End) and is still widely read.

Abd al-Ghani al-Nabulsi (1641-1731) was a mystic poet and prose writer. He belonged to an old Damascene family. At an early age he showed interest in mysticism and spent seven years in isolation in his house, studying Ibn al-Arabi and others. One of his early poems was of such virtuosity, that his authorship was doubted; he vindicated himself by writing a commentary on it. Abd al-Ghani traveled extensively and wrote more than 200 books.

His works are not restricted to mysticism and poetry but include (mystical) travel accounts and treatises on a wide variety of subjects, such as correspondence, prophecy, the interpretation of dreams, and the question of the lawfulness of the use of tobacco. Although he was an original thinker, his travel accounts are considered by many to be the most important of his writings.

Of less noble descent and also less productive was Ahmad al-Budayri al-Hallaq, a Damascene barber (hallaq). His diary, spanning a period from 1741 until 1762, provides useful information on daily life in 18th century Damascus. In the 19th century, when Ottoman censorship in Syria (and Lebanon) increasingly began to stifle writers and intellectuals – especially in contrast with the more liberal climate in Egypt – many migrated to Egypt and, in smaller numbers, to America.

Modern Literature

Contemporary Arabic literature has its basis in the Nahda, the movement of cultural revival which began in Egypt during the 19th century, although some of its roots can be traced back to an earlier period.

The Nahda accrued from two seemingly contradictory developments: the encounter with European culture and the revaluation of the classical Arabic cultural heritage. Lebanese and Syrian intellectuals with a Christian background, who traditionally maintained close ties with the European Roman Catholic Church, played an important role in both movements. As a result of the persecution of the Christian and Druze populations in the 1860s, they migrated in large numbers to Egypt, where they contributed greatly to the Nahda.

Among the foremost Syrian-Lebanese representatives of the literary Nahda were Salim al-Bustani (1846-1884), who translated and adapted mainly French literature, Francis al-Marrash (1836-1873), author of prose poems who deeply influenced the world famous American-Lebanese poet Gibran Khalil Gibran, and Maruf Ahmad al-Arnaut (1892-1948), who introduced the historical novel into the literary spectrum.

The contemporary Syrian novel

Many critics and scholars agree that the first fully-fledged novel of literary merit was Naham (Desire, 1937), a highly romantic work, written by Shakib al-Jabri (1912-1996). The 1940s and 1950s were marked by a gradual but clear shift from romanticism towards (socialist) realism, influenced by Russian authors like Maxim Gorky. The first realistic novel appeared in 1954, written by Hanna Mina (ca. 1924), a fervent supporter of the Baath regime, who played a major role in the development of the Syrian novel from the 1950s to present times.

Other literary trends in the 1960s were: revolt without ideology (Haydar Haydar), mystic spiritualism (Abd al-Salam al-Ujayli) and fantasy with a political content (Walid Ikhlasi). The same period witnessed the emergence of women in the literary field, including Ulfa Idlibi, Ghada al-Samman, Colette Khoury and many others, who generally focused on the position of women in the Syrian society.

The traumatizing outcome of the wars of June 1967 and October 1973 resulted in a reinforcement of social criticism in literature, represented by the surrealist writer Zakariya Tamir and the Kurdish writer Salim Barakat, whose novels are marked by a magic realist touch. This disaffected attitude towards Arab society in general and internal Syrian politics in particular, is nowadays pursued by Khaled Khalifa, who heavily criticized the Syrian aggression against the Muslim Brotherhood in the 1980s in his novel Madih al-Karahiya (In Praise of Hatred, 2006), the poet-writer Khalil Suwailih and the writer and journalist Dima Wannous.

Bashar al-Assad, who assumed power in 2000, initially seemed to show some leniency towards the political opponents among the Syrian intellectuals, but shortly thereafter he tightened the reins again by suppressing publications, intimidating dissident writers, and lately by blocking critical websites.

Contemporary Syrian poetry

In the second half of the 19th century the so far traditional and formalistic neoclassical Syrian poetry underwent a radical change. Initially most poets kept to the old poetical structures, but their choice of topical themes was innovative. In the 1920s and 1930s the classical form was still maintained, but there was a substantial wave of individualistic, romantic poetry, partly influenced by the British poetic tradition.

It was the Mahjar movement (a group of Lebanese poets and writers who had migrated to North and South America in the late 19th century) that instigated the liberation from the straightjacket in which most poets were caught. The famous Syrian poet and intellectual Nizar Qabbani (1923-1998) first wrote his poetry in classic forms, but after 1956 he turned to experimental poetry.

In the 1970s the way was finally cleared for new forms of poetry, such as the free verse, the prose poem and the mystical ‘neo Sufi trend’, of which the world-famous poet and leftist cosmopolitan Adunis (alias of Ali Ahmad Said, 1930) was the leading exponent. Surprisingly, this same Adunis, who sympathized with the Tunisian and Egyptian rebels during the uprisings of January 2011, lately showed his loyalty to the Syrian President Bashar al-Assad by sending him an open letter of support.

After a wave of criticism by Syrian and Arab writers he reconsidered his point of view and advised al-Assad to step down, but not without accusing the opposition for being fragmented and dominated by religious groups.

Museums

Syria has many archaeological and artistic treasures. Unfortunately, many museums or archaeological sites are in dire need of maintenance and/or renovation. In addition, little attention seems to be paid to the need to preserve an archaeological site, or to make it more attractive and more accessible.

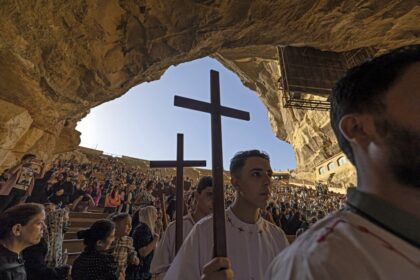

Among the many archaeological and architectural treasures, the temple complex in Palmyra and the Roman theatre in Bosra (see UNESCO World Heritage List) are some of the most impressive. Among the first Christian monuments are the well-preserved ruins of ad Qalat Semaan (Dayr Saman), a 5th century Byzantine church dedicated to Saint Simeon. In the same region, around Aleppo, several ‘Dead Cities’, abandoned villages, can be visited.

The Old City of Aleppo is also listed by UNESCO as a World Heritage site. It has a vast souk, and its Great Mosque was built by the sixth Umayyad Caliph al-Walid I, who earlier built the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus. In 1260, the Mosque in Aleppo was destructed by the Mongols. East of the Old City rises the Citadel. The Citadel was built by the Ayyubids during the 12th century, and was later extended and strengthened by the Mamluks.

In Damascus, the Umayyad Mosque (UNESCO World Heritage List) attracts hundreds of tourists every day. It was also built by the sixth Umayyad Caliph Walid I in the 8th century on the site of a Christian church, which in turn had replaced a Roman temple.

The National Museum in Damascus, hidden behind a shady Sculpture Garden, exhibits archaeological finds from all the important archaeological sites in Syria, from the ancient city of Ugarit to Palmyra. It also contains an old synagogue (3rd century), found in Dura-Europos, which was removed from the site and rebuilt in the museum.

Music

Syria’s music is part of the Arab tradition. However, at the crossroads of different cultures, it also benefits from various other influences – Turkish, Kurdish, and Persian as well as Egyptian. Some singers are revered across borders, such as the legendary Egyptian singer Umm Kulthum and the Lebanese singer Fairuz. But the Syrians also have their own legendary singer-actor and ud player Farid al-Atrash (1915-1974). Singer Lena Chamamyan is also on her way to becoming a legend.

The ud is the traditional instrument. The Syrian ud is slightly larger and longer than the Persian or Turkish ud. It is still popular, and often played in small ensembles together with the kamanja (spike fiddle), qanun (box zither), darbuka (goblet drum), and daf (tambourine). These ensembles play traditional music such as muwashshah, which is especially popular in Aleppo and related to some forms of Andalusian music. Younger musicians sometimes mix the traditional instruments and sounds to make modern music and rhythms.

Jazz is very much alive in Syria. Every year in June, the Jazz Lives in Syria Festival is held both in Damascus and Aleppo. There is even a Syrian Jazz Orchestra; since the creation of this festival in 2005, at least eight new jazz bands have been founded. Guitarist Hannibal Saad’s big band includes singer Ribal al-Khudari, who is also known as a performer of more traditional music.

Traditional dances are still performed, such as the dabke, which varies according to the region, or the sama, which is still danced in Aleppo and is said to derive from a Sufi ceremony.

Sports

The most popular sport by far is football (soccer). However, although the Syrian football team performs reasonably well at the regional level, they have never passed beyond the qualifying stage of the World Cup. In October 2020, Syrian’s national football team ranked 79 in FIFA’s world ranking table.

Syrian wrestlers and weightlifters fare much better. At the 2009 Mediterranean Games, Syria won 12 medals: 2 gold (weightlifting), 3 silver (wrestling), and 7 bronze (wrestling, weightlifting, karate, boxing, and judo). Also in 2009, the Syrian women cyclists won one bronze and two gold medals at the Arab Cycling Championships. At the 2004 Olympics in Athens, the heavyweight boxer Nasser al-Shami won a bronze medal. The only Olympic gold medal was won in the heptathlon by a woman, Ghada Shouaa. After becoming World Champion in 1995 in Gothenburg, she won a gold medal at the 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta.

Other sports that are well-watched in Syria include basketball, tennis, and swimming. The Syrian basketball national team won the Pan Arab Tournament in 1992 and reached the semi-finals of the 2001 Asian cup tournament in Shanghai.

Theatre and Film

Syrian cinema is not well known outside the country, except for a few directors’ films. Abdullatif Abdulhamid‘s first film, The Nights of the Jackal (1989) won international praise. His other films include Verbal Messages (1994), The Ascent of the Rain (1995), The Spirit Breeze (1998), Two Moons and An Olive Tree (2001), Listeners’ Choice (2003), Out of Coverage (2007) and Days of Boredom (2008). Another award-winning Syrian director is Ghassan Shmeit, who made Something Is Burning (1993), The Black Flour (2001), Roses and Thorns (2003), and ID (2007). Mohammad Malas (Dreams of the City, 1984, and The Night, 1992) should also be mentioned.

Omar Amiralay made excellent documentaries, such as Everyday Life in a Syrian Village (1974), about the construction of the dam on the Euphrates in order to create Lake Assad, and A Flood in Baath Country (2003), about the flood caused by the same dam a few years later. Amiralay does not appear in the listing of the Syrian National Film Organization, which falls under the Ministry of Culture, as his last film was critical of the Baath regime.

The same listing mentions only two films by another important film director, Osama Mohammad, The Stars of the Day (1988) and Peep Show (2002), although he made many more, including Step by Step (1977) and Stars in Broad Daylight (1988). Many Syrian directors studied in Moscow.

Films are financed by the National Film Organization. At first glance, this seems favorable for film makers. However, films can be banned upon completion and kept out of Syrian cinemas, apart from a first screening at the (prestigious) Syrian Film Festival, which is held annually in November. In addition, directors often have to wait for years before film grants are awarded. At times, censorship forces them to take refuge in symbolic language or historical subjects.

Traditional Architecture

Syria’s past can be seen everywhere in its historical architecture. There are Roman temples – in Palmyra and in Baalbek, to name but two. Magnificent buildings from the Umayyad era have survived, such as the Umayyad Mosques in Damascus or Aleppo, as have early Christian churches – sometimes forming the foundation on which mosques were subsequently built. Remnants of the crusade era can be viewed, such as the Krak des Chevaliers (Qalat al-Husn), a fortress near Homs. The Mamluks left their fortresses, the Ottomans their numerous khans (caravanserais).

Latest Articles

Below are the latest articles by acclaimed journalists and academics concerning the topic ‘Culture’ and ‘Syria’. These articles are posted in this country file or elsewhere on our website: