Introduction

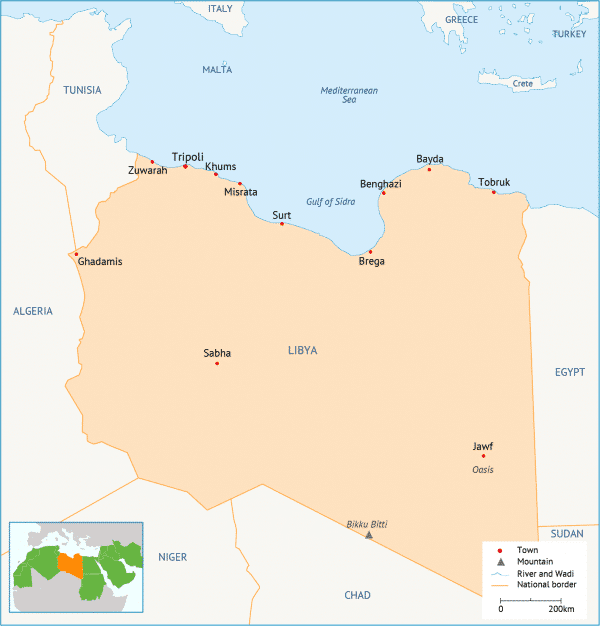

Libya, North Africa’s smallest country in terms of population, has been torn apart by civil war and rival governments since 2011, when dictator Muammar Qaddafi’s 40-year rule came to an end.

The post-Qaddafi years have been characterized by a power vacuum, in which armed militias have never been under the control of the central state. In 2014, the conflict escalated when Qaddafi-era army commander Khalifa Haftar launched an operation from the eastern city of Benghazi to clear Libya of Islamist militias, most notably Libya Dawn, which had seized control of the capital Tripoli.

The operation divided the country, and three different governments are now vying for legitimacy: one backed by Haftar’s troops, based in Tobruk in the east, one in Misrata affiliated with Libya Dawn and one in Tripoli, which came into being in 2016 after extensive UN-led negotiations. The lack of government control over the security situation has led to foreign companies deciding to wait to enter Libya until the situation improves.

Libya is a member of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), but since the beginning of the conflict, the drop in oil production has provided an opportunity for other OPEC countries, particularly swing producer Saudi Arabia, to increase crude oil production to make up for the reduction in Libyan production. However, OPEC’s agreement in November 2016 to limit production in a bid to increase oil prices has been frustrated by Libya’s recovering oil sector.

Primary energy consumption per capita before the war was 0.781 quadrillion Btu, which is typical for an economy with plentiful hydrocarbons. Since late 2010, Libya’s oil and gas sector has been affected by violence, civil war and political instability, and total energy production has fallen dramatically. After the first phase of the civil war ended in 2012, oil and gas companies made investments to restore production, but the renewed fighting in 2014 reduced production and investments again. Libya’s electricity infrastructure was also damaged, and it will take some time to recover to 2010 capacity levels. This is covered in more detail in the following sections.

Oil

Libya’s oil sector is in the process of restoring itself to pre-war levels, which is structurally hindered by recurrent fighting. Libya has enormous crude oil reserves to exploit, and oil is the heart of the Libyan economy. A conservative estimate of proven crude oil reserves is 48.4 billion barrels. This is the largest amount of reserves of any country in Africa, and in the broader region only five countries on the Persian Gulf have higher proven crude oil reserves.

Estimates of Libya’s reserves have been increasing in recent years, as renewed exploration in the 2000s after Libya reopened to investment from Western countries was successful.

As Table 1 shows, after a steady increase in production in the 2000s, Libya’s production fell precipitously in the first three quarters of 2011 as foreign oil companies and workers fled the country to escape the violence; infrastructure was damaged intentionally or unintentionally; and the refineries and ports that take that crude oil ceased operation.

By the end of September 2012, crude oil production had recovered to 1.6 million barrels per day (mb/d), slightly less than pre-war levels, and the government was planning to step up production. However, from 2013 onwards, oil output plummeted again to less than 300,000 barrels per day (bpd) and has remained unstable since.

A big blow to production came in 2014, when a militia affiliated with the Petroleum Facilities Guard (PFG) claimed control of the key oil ports in central Libya – Sider, Ras Lanuf and Zueitina – closed them and suspended all operations, forcing oilfields supplying these ports to cut production.

The PFG stem from former rebels fighting Qaddafi in 2011, who were trained in 2012 by the Libyan government to become oil facility security guards, in the hope that providing employment for these groups would create more stability.

In September 2016, forces loyal to the Libyan National Army (LNA), led by Khalifa Haftar, took control of the ports, allowing operations to resume and production to recover.

Output has since continued to be fairly unstable, however, depending on which of the rival factions controls – the one closing, the other reopening – the pipelines, but all in all, it is showing an upward trend.

Oil production hovered around 900,000 bpd in the first half of 2017. Production has primarily been boosted by the reopening of the Sharara field in December 2016, which has a nominal capacity of around 270,000 bpd, and an interim deal with Germany’s Wintershall sealed in July 2017, which accounts for at least 160,000 bpd.

Sharara is, however, still experiencing frequent disruptions. For instance, its production was reduced in August 2017 following security breaches. The field is operated by Akakus, a joint venture between Libya’s National Oil Corporation (NOC), Spain’s Repsol, Austria’s OMV, Total and Norway’s Statoil.

NOC chairman Mustafa Sanalla said in January 2017 that oil production could reach 1.22 mb/d by the end of the year, and that some $15 billion in investment was required over the next five years to bring output up to a potential 2.1 mb/d. Nonetheless, everything depends on whether a reliable group aligned with either the United Nations-backed government or Khalifa Haftar’s LNA is able to secure and retain control over the fields, ports and pipelines.

In April 2017, the state-owned Arabian Gulf Oil Company (AGOCO), which is the largest oil producer in Libya, inaugurated five new wells in its VV field, with an average output of 10,000 bpd.

VV is one of eight oilfields under development, in addition to three gas fields in concession 65, located north of Sarir and south of Messla.

The largest foreign producer as of the first quarter of 2017 is Repsol, with a total production of 15 million barrels in that period, largely due to the restart of Sharara. Eni comes second, followed by Total and Wintershall.

OMV said in February that it expected its production from Libya to average 10,000 bpd in 2017. Earlier this year, it increased its stake in four exploration and production-sharing agreements (EPSAs) in the Sirte Basin, acquiring interests previously held by the US-based Oxy.

The major oil export terminals are Sider, Ras Lanuf, Marsa al-Brega, Zueitina, Zawiyah (Tripoli) and Marsa al-Hariga (Tobruk).

Refineries

Prior to the war, Libya’s five refineries had a nameplate crude oil throughput capacity of 378,000 bpd, but the capacity suffered greatly in the war. The largest, Ras Lanuf (pre-war capacity of 220,000 bpd), has been damaged in the war and is currently not operating. The second-largest refinery, Zawiyah, near Tripoli, was also damaged but restarted in November 2011 and is currently the only operating refinery.

The three smaller refineries are at Tobruk, Sarir and Marsa al-Brega, with a combined capacity of less than 40,000 bpd. Work is being done to repair the Tobruk refinery and restart operations.

Consumption in Libya is about an estimated 220,000 bpd as of 2014, according to the US Energy Information Administration, which is high given the relatively small population. Although fuel oil exports to Europe have resumed, even prior to the war Libya had to import higher value products such as gasoline.

Given the decline in throughput at domestic refineries, exports of petrochemical products went down from 2.5 million tonnes in 2010 to 667,000 tonnes in 2016. Libya’s oil exports reached 111 million barrels in 2016, down from 419 million barrels in 2010.

The Libyan government also owns two refineries and a product distribution network in Europe through the NOC’s Oilinvest (Tamoil) subsidiary (headquartered in the Netherlands). During the civil war, a special foundation set up by the Dutch government kept the assets in trust for a future Libyan government.

Natural Gas

Like the oil sector, the natural gas sector has suffered damage during the civil war. Exports through the Greenstream pipeline to Italy were suspended for much of 2011. The natural gas sector plays a smaller role than the oil sector in Libya’s economy, but the earnings are still significant.

A conservative estimate of Libya’s proven dry natural gas reserves in publications such as Oil & Gas Journal is 1.49 trillion cubic metres (TCM). The NOC has publicly stated that the figure is a bit higher, at 1.55 TCM.

Libya’s gas production reached 22 billion cubic metres (BCM) in 2016, much lower than pre-war levels, which stood at 30.5 BCM in 2010.

NOC chairman Sanalla said in January 2017 that Libya is aiming to increase its production of natural gas by a further 36,800 cubic metres per day in 2017, thanks to higher volumes from the offshore Bahr Essalam field.

The NOC intends to develop a new phase of the Bahr Essalam field over the coming years, and signed a $500 million deal with France’s Technip in 2016 to work on the project.

Sanalla also mentioned other potential projects, including a new refinery in Ubari, in southern Libya, and work to develop the Marisa port and free zone project near Benghazi.

In April 2017, Italy’s Eni made a new gas/condensate discovery in the offshore Tripoli-Sabrata basin. A new well, B1-16/3, is located 140km north of Tripoli and 5km from the existing Bahr Essalam gas field, and has gas rate of 18 million cubic feet per day (MMcf/d).

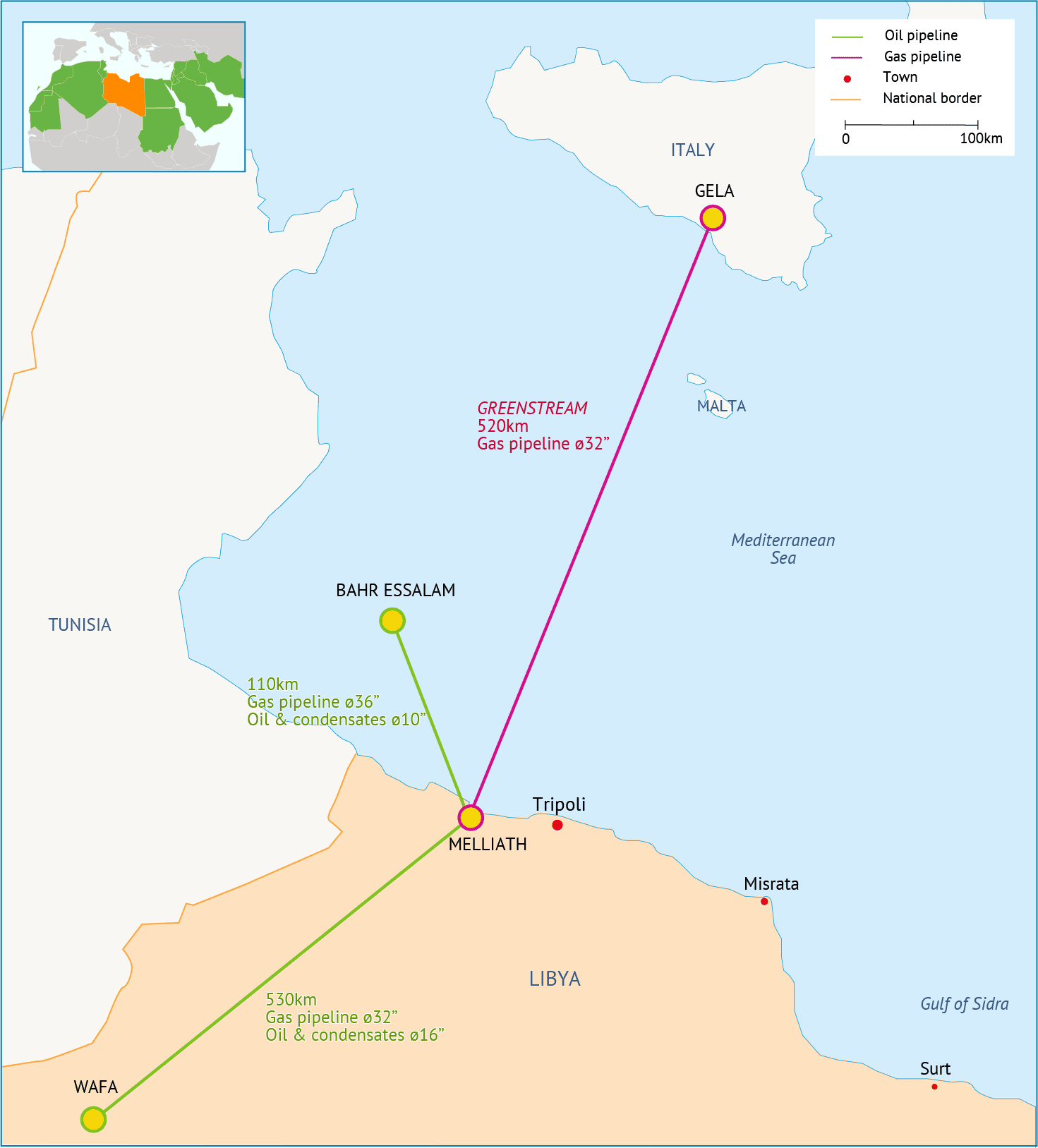

Libya started to become a significant gas producer in 2003, when the Western Libya Gas Project (WLGP), operated by Eni and NOC through the Mellitah Oil & Gas joint venture, came online. The WLGP, which includes the offshore Wafa and Bahr Essalam fields, nearly tripled production (Map 2). Most other natural gas in Libya is produced by the NOC and its Sirte Oil Company subsidiary in the onshore Sirte Basin.

WLGP enabled Libya’s main export project, the Greenstream pipeline, which draws from WLGP. This pipeline is 540km and runs from Mellitah on the extreme west of Libya’s coast to Gela on the Italian island of Sicily. Capacity had reached 11 BCM, although even before the war the pipeline was running at less than full capacity at about 8 BCM per year. Hence, Greenstream supplied slightly less than 10 per cent of Italy’s demand. Exports ceased between March and November 2011. In 2016, the pipeline exported 4.4 BCM.

In the past, Libya exported liquefied natural gas (LNG) from its aging facility at Marsa al-Brega, but because of rising domestic consumption and unused capacity in the Greenstream pipeline, the NOC made the decision in October 2012 not to invest in renovating and restarting the plant, which has been shut down since the war. Royal Dutch Shell signed a contract to modernize the plant in 2010 (in part to access exploration acreage) but has since pulled out of Libya. The company lifted its first crude oil cargo from Libya in August 2017.

Electricity

Libya continues to suffer a severe power shortage as several power plants have been damaged in the war. There is a lack of cash and foreign companies to undertake maintenance and complete suspended projects. Libya’s electricity grid has been separated into several isolated grids due to damage, mostly inflicted during the 2014 fighting.

As a result, the General Electricity Company of Libya (GECOL) is forced to implement blackouts to avoid a possible collapse of the grid.

GECOL said in June 2017 that the grid’s available production stands at 4,900 megawatts (MW), whereas demand reached 6,500 MW, with a deficit of 130 MW in the east and 1,470 MW in the west.

The west, which includes Tripoli, is expected to have five to eight hours of blackout per day, while the east will have one to four hours without power.

Peak load in 2016 was only around 7,000 MW, according to GECOL statistics.

Some 49 per cent of power in Libya is generated using combined cycle power plants, 40 per cent gas plants and 11 per cent steam (usually fuel oil-fired).

Before the civil war, in 2010, generation capacity reached 6,196 MW, which was enough for Libya to export electricity to Egypt.

Libya has a completely state-owned electricity sector, with generation, transmission and distribution under the auspices of GECOL, which also operates desalination plants.

In 2010, Libya generated 30.43 billion kWh. Domestic demand that year was approximately 25.87 billion kWh. Demand was expected to increase once Libya was back on the pre-war demand trend line, which would require adding new capacity on top of the repairs to restore capacity to 2010 levels.

Plans had begun to expand capacity before the war, with thermal plants planned or under construction, including the al-Khaleej power plant at Sirte with installed capacity of 1,400 MW, Tripoli West power plant-expansion (1,400 MW), the Misrata power plant (750 MW), the Benghazi combined cycle plant (750 MW) and the Sarir simple cycle power plant (750 MW) at Ubari.

The majority of work was completed on the Benghazi, Misrata and Sirte plants by 2012, but construction has been frustrated since foreign companies left the country. Currently, a number of plants are being constructed or are starting operations.

New and Planned Power Plants

Khoms fast-track power plant, which was built by Turkey’s Çalık, began operating in November 2016. It has an overall capacity of 530 MW generated through two gas-fired units with a capacity of 263 MW each.

In early 2017, Turkey’s Enka returned to complete construction work of the Ubari power plant, which was then said to be more than 95 per cent finished.

The project, which was initially launched in 2012 at a projected cost of $522 million, had been suspended since September 2014 due to security issues and the departure of staff.

The gas-fired plant was set to receive natural gas from the Sharara field and to be composed of four 160 MW units. The plant was scheduled to start operating before the end of 2017.

In August, Siemens signed an agreement with GECOL to work on the plant, with no clear time schedule for completion.

In April 2017, GECOL signed a memorandum of understanding with Greece-based Metka to build a 736 MW power plant in Tobruk. The project was estimated at $380 million, but the time schedule is not clear.

Future Expansions

GECOL has plans for a large power capacity expansion programme in the coming ten to 15 years, although its development depends entirely on the availability of funds and details remain scare.

GECOL has plans for a large power capacity expansion programme in the coming ten to 15 years, although its development depends entirely on the availability of funds and details remain scare.

GECOL is reportedly in talks with contractors who were working on suspended or partly completed projects with a capacity of around 4,083 MW. These include the Khoms steam-fired plant and the Ubari plant.

Fast-track projects aimed at reducing the current power deficit, according to GECOL, are as follows:

Around 5,075 MW of capacity were planned for 2016-20 but have not yet been contracted. A further 6,075 MW of new capacity is envisaged in GECOL’s 2021-2030 plans, including facilities in Sebha, Derna, Tripoli, Khoms, Tobruk and Benghazi.

GECOL said it forecast peak load to rise to 10,795 MW by 2020, then to 14,834 MW in 2025 and 21,669 MW by 2030.

| Location | MW | Type |

| Tripoli West | 600 | Gas |

| Tripoli East | 1,400 | Steam |

| Misrata | 600 | Gas |

| Tobruk | 740 | Gas |

Those estimates are based on an optimistic assumption of economic recovery in Libya and greater demand from the industrial and energy sectors in particular. Foreign sources of investment, whether from international organizations or the private sector, seem unlikely in the current unstable and often violent state of the country.

Electricity Grid

Libya’s cross-border interconnections with Tunisia and Egypt have been disconnected amid the ongoing conflict.

Libya’s grid is connected to Egypt via a 220 kilovolt (kV) double-circuit overhead line (OHL). The interconnection was supposed to be reinforced with a 500 kV extra-high-voltage (EHV) line on the Egyptian side and 400 kV on the Libyan side, but the project appears to have stalled. There are also two 220 kV transmission lines connecting the Libyan grid with Tunisia, one double-circuit line along the coast and one single-circuit line through the Sahara Desert connecting Rowis in Libya and Mornaguia in Tunisia.

When the security situation improves, it will take six months to repair and revive the Libyan transmission system at a cost of some $100 million, according to GECOL estimates. With the instability continuing, the grid will remain disintegrated and blackouts will continue to be a daily occurrence.

Renewables

There is enormous potential for renewables in Libya, particularly since some parts of the country receive the world’s highest amounts of solar radiation. As per 2012, the Ministry of Electricity and Renewable Energy planned for 10 per cent of Libya’s electricity supply to be sourced from renewables (wind as well as solar) by 2030. So far, there is one project in progress: a 27 MW wind farm in Msallata, which is due to start operation by the end of 2017. Another 60 MW wind project in Derna has been halted due to security concerns.