The beginnings of Italian hegemony

Apart from the Ottoman Empire itself, Britain and Italy were most involved in opening Tripolitania to the European economy. This was part of a wider imperialist and colonialist plan in which Europeans extended their reach in North Africa, usually in rivalry with each other. Britain, France and Germany were the leaders, with Italy and Spain forming the second rank.

Italian involvement in Africa was initially centred on Somalia and Ethiopia. But the Ethiopian army defeated the Italians at Adawa in 1896, one of the worst defeats of a European power in colonial history. That meant that Italian nationalist politicians, with a lust for an imperial identity, came to identify Libya as a suitable colony. There was already a significant Italian presence through the Banco di Roma, other trading houses and Italian schools. Jewish middlemen and traders spoke Italian and some of them were Italian citizens.

At the same time, Tripolitania and Cyrenaica had strategic value when the rest of North Africa was being divided by Britain and France in a way that excluded Germany. In 1904, in exchange for a free hand to the British ‘veiled protectorate‘ in Egypt, France got freedom of action in Morocco alongside existing French control of Algeria and Tunisia, with a nod to Spanish ‘interests’ in northern and southern Morocco.

In 1902 other European states agreed to recognize an Italian hegemony in Libya. In return, the Italian government recognized an agreement made in 1899 by the French and British governments that defined the northern limit of French colonial expansion. This would become the southern boundary of the Italian colony in Libya.

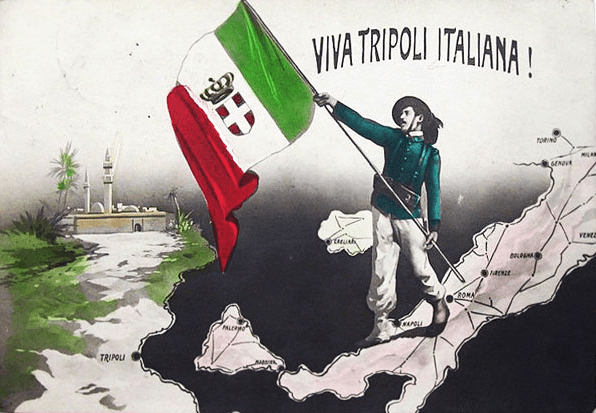

In reality, what would become Libya offered very few practical advantages to the Italian economy. However, for imperial enthusiasts there was a symbolic benefit: Libya provided the promise of a ‘fourth shore’ (cuarta sponda) for Italy, which would demonstrate that Italy was a viable military and political power. There was also a huge surplus population in Italy: control of Libya offered the possibility of settling there huge numbers of Italians who would otherwise have emigrated to the United States or South America. This was accompanied by imperialist myth making about the economic possibilities of developing agriculture in Libya. Opponents of imperialism were sceptical. A socialist deputy in the Italian parliament aptly described Libya as a ‘barrel of sand.’

The road to Italian occupation

Ottoman policies in Libya were also changing. The oppressive government of Sultan Abdul-Hamid II used Libya as a place of exile for its opponents, who introduced radical ideas to the Libyan elite. At the same time, Ottoman policies of Turkification and the resulting neglect of Arabic, caused dissatisfaction. In 1908 the Young Turk revolution in Istanbul brought a return of constitutional government to the Empire, and Tripolitanians joined the parliament in Istanbul, including Sulayman al-Baruni, an Ibadi Muslim.

In 1911 the Italian government complained that the Ottomans were impeding Italian enterprise in Libya. They sent an ultimatum giving the Ottoman Empire twenty-four hours to agree to an Italian occupation of Cyrenaica and Tripolitania. On 29 September they declared war. This was followed by invasion.

The Istanbul government organised resistance and nationalist (Young Turk) officers soon arrived in Libya. They found much support among the Libyan population. Neither the Italian nor the Ottoman army was very efficient, but the Ottoman leadership had no outside diplomatic support and was fighting in the Balkans to keep its empire there intact. In October 1912 Italy and the Ottoman Empire signed a treaty and the Ottomans gave Tripolitania and Cyrenaica autonomy and withdrew their forces. The Italian government then annexed both provinces.

Armed Resistance

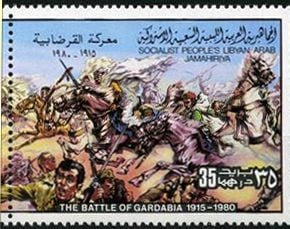

After the Ottomans withdrew, local fighters continued the resistance to the Italians. There were several local attempts to organise resistance among the Ibadi Amazigh in the mountains of north-west Libya and around Misrata, as well as in the Fezzan. In April 1915 local Tripolitanian forces defeated the Italian army at the battle of Gardabia (or Qasr Bu Hadi). The Italians then withdrew all their forces to the coast.

When the Libyan leader Muammar Qaddafi addressed the Libyan people on television after the start of the revolution that would bring him down, he boasted that ‘My grandfather, Abdul Salam Buminyar, was the first martyr to fall in al-Khums during the first battle in 1911.’

Cyrenaica provided the most determined resistance, led by men from lower-status tribes, as the Sanusi leadership was increasingly collaborating with the Italians. As part of the secret diplomacy of the First World War in the Middle East and North Africa, Britain, France and Russia secretly agreed to divide the Ottoman Empire between them once the war ended. They divided Greater Syria between Britain and France (Sykes-Picot Agreement, 1916) and promised King Husayn of the Hejaz to help found an Arab state after the war. They used similar tactics in Libya.

The pattern was similar to what the allied powers had already agreed over Libya. In 1915 in the secret Treaty of London, Britain, France, and Russia promised Italy favourable treatment in gaining colonies if it joined them. In 1917 the British persuaded Muhammad Idris, who had become the new head of the Sanusi order, to negotiate a political settlement with the Italians, under which he would become Amir (prince) of Cyrenaica, with autonomous authority over the inland parts of Cyrenaica.

After the war, the Italian government toyed with this principle of autonomy. They did recognise Muhammad Idris al-Sanusi as the Amir of Cyrenaica, but his autonomy was very limited. In Tripolitania, local nationalist leaders declared independence (the Tripolitanian Republic) and initially the Italian government seemed willing to negotiate with them. Quite soon the leaders of the Tripolitanian Republic fell out among themselves.

These arrangements soon broke down. In any event, autonomy would not survive the arrival in power of the new fascist regime that took over Italy in late 1922.