Introduction

The Libyan cultural identity is a colored mosaic, and a harmonious and intertwined mixture of Amazigh, African, Moroccan and Islamic Arabian cultures. The emergence of media in Libya constituted the cultural movement’s initial features since the era of the Ottoman rule (1865 – 1911). Where local journalism thrived and played a significant role in spreading political awareness and enhancing cultural identity.

The period of the Italian occupation (1911 – 1943) was characterized by what could be referred to as cultural and intellectual stagnation in the country. Researchers confirm that Italy was neither concerned with promoting the original Arabian culture in Libya, nor with teaching Libyans valuable culture.

After Libya was subjected to the British and French military administration in 1943, the country’s new administration allowed a relative freedom of speech, leading to the emergence of cultural clubs, professional associations and sports clubs. During the royal Senussi rule (1951 -1969), intellectual and literary societies, cultural centres and clubs spread on a larger scale, with the supervision and support of the government.

However, Muammar al-Gaddafi who ruled the country for 42 years (1969 – 2011) worked on reforming the Libyan culture through his own ideas, and he began to monopolize thoughts; as some critics argued that he did not only imprison physical bodies, but also the minds of intellectuals in Libya.

Despite the suffering of many intellectuals from oppression and harassment, free voices did not submit. They searched for safe havens to fight in their own way. In this manner, Colonel Gaddafi’s Libya displaced its shining minds and intellectuals. Those who remained home were the ones who mastered the arts of chanting for the colonel and cheering for his greatness and the grandeur of his ideas.

After the 19th of February 2011 revolution, Libyan culture finally broke its shackles and expressed their oppressed creativities, be it in the form of short documentaries, music, dancing, literature, poetry and other kinds of arts.

Despite the political and military conflicts that followed the revolution for about two decades until now (2020), Intellectual writers and artists started enjoying a free era with no fear of Gaddafi’s dictatorship. The culture of the new era has come and began to set the literature of the new phase, in remarkable response to both national and humanitarian aspirations, in quick attempts to get over the past, unfolding the new future of Libya with liberated means, opening up to diverse cultures.

To learn more about the culture of Libya, check what Fanack has covered about this file.

Literature

Libya does not have the same intellectual history as other Arab countries: it was for too long a remote and underpopulated place. The Karamanli period produced one major chronicle account by the court historian Muhammad ibn Khalil ibn Ghalbun (d. 1737), al-Tadhkar fi man malaka Tarabulus wa-ma kana bi-ha min akhbar (On who holds power in Tripoli).

Another political writer was the late-19th- and early-20th-century political leader Sulaiman al-Barouni, an Ibadi from the Jebel Nafusa region. His father was a theologian, jurist, and poet who taught at a zawiya (Sufi lodge) near Yafran. Sulaiman himself studied in Tunis, at the al-Azhar in Cairo, and in the Mzab in Algeria. Throughout his life he was committed to the Ibadi cause and was persecuted by the Ottoman authorities as a result, although he served in the Ottoman parliament after the Young Turks’ revolution of 1908, as a deputy from Jebel Nafusa. He worked with the Ottoman government, before and during World War I, to resist the Italian conquest of Libya.

After the war, he helped establish the Tripolitanian Republic and subsequently sought to set up an autonomous Berber emirate in the western Jebel under Italian protection but fell out with the mainstream Sunni Arab population, who accused the Ibadis of heresy. He fled first to Europe, then to the Hejaz, and then to Muscat, as a guest of its sultan. He then moved to the interior of Oman as the minister of the small Ibadi state of Nazwa before returning to Muscat 1938, as adviser to the sultan. Al-Barouni wrote a multi-volume account of Ibadi rulers (al-Azhar al-riyadiya fi aimma wa-muluk al-Ibadiya, of which volume 2 was published in Cairo in 1906-1907). A small museum in Jadu, in the Jebel Nafusa, is dedicated to his memory.

The real blossoming of Libyan literature came in the Gaddafi period. Of the authors who lived through the regime, some were more supportive of it than others. Ahmed Fagih (born in Mizda in 1942) was educated in Libya, Egypt, and Scotland; he received his doctorate in literature at the University of Edinburgh in 1982. On his return to Libya he was a newspaper columnist, diplomat, journalist, and director of an institute of music and drama in Tripoli. He was also a novelist and playwright; five of his novels have been translated into English. His trilogy Sa-ahabuka madina ukhra (I’ll give/offer you another city) (London, 1991) was translated into English as Gardens of the Night (London, 1995) and was listed sixteenth in the Arab Writers’ Union list of the hundred best Arabic novels of the 20th century.

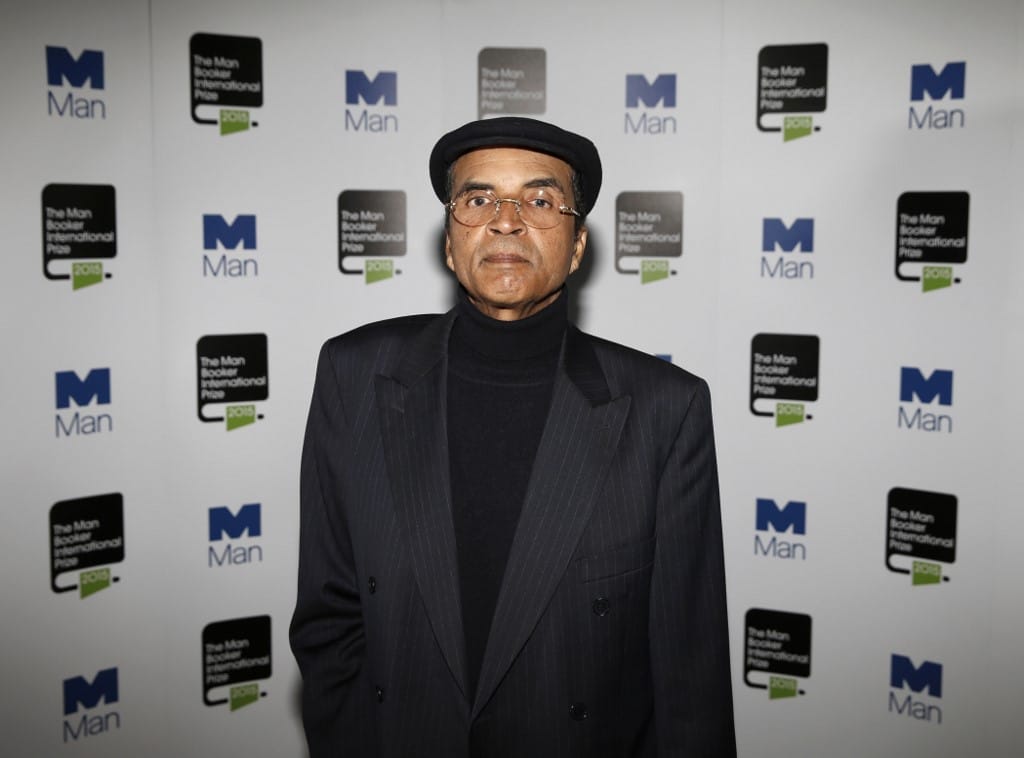

Libya’s most famous author from this period is Ibrahim al-Koni. He was born in 1948 in Ghadames, studied comparative literature at the Maxim Gorky Literature Institute in Moscow, and worked as a journalist in Warsaw and Moscow. He now lives in Switzerland. He writes with nostalgia about the past and the nomadic Tuareg culture from which he hails. In 2010 he received the Arab Novel Award in Cairo and donated the value of the prize to the children of the Tuareg tribes. He has also received several other awards, including the Swiss State Award for his novel Bleeding of the Stone (Nazif al-hajar) in 1995, the Libyan State Award for all his work in 1996, and the Japanese Translation Committee Award for Gold Dust (al-Tibr) in 1997. His novels include: al-Majus (The Animists; Libya and Morocco, 1990), which was listed as eleventh in the Arab Writers’ Union list of the hundred best Arabic novels of the 20th century; Anubis (Beirut, 2002; translated as Anubis: A Desert Novel by William M. Hutchins, 2005); al-Dumya (Beirut, 1998, translated as The Puppet by William M. Hutchins, 2010); al-Bahth an al-makan al-dai (Searching for a lost place, Beirut 2003, translated as The Seven Veils of Seth by William M. Hutchins, 2008).

Another member of this post-independence generation of writers is Khalifa Husseinn Mustafa (born in 1944), whose novel Eye of the Sun (Tripoli, 1983) was also listed in the Arab Writers’ Union’s list of the top hundred Arabic novels of the 20th century. Poets include the men Gillani Trebshan and Idris Tayeb, and women Mariam Salama and Khadija Bsikra. Lutfia Gabayli is an editor and writer of short stories.

Despite this appearance of energy, cultural life was very limited under Gaddafi. The writer Hisham Matar has described how the army went to every bookshop and library in Tripoli and took away thousands of books to be burned in one of the public squares. All that remained on the shelves were ‘educational’ or ‘revolutionary’ books. The biggest bookshop and publishing house in Tripoli, Dar Fergiani, which was set up in 1952, moved to London in 1980 and remade itself as Darf Publishers, concentrating on English-language books on Libya, the Middle East, and the Arab world.

It was a similar story in other aspects of cultural life. Numerous associations and societies were founded, such as the Ibn Muqla Institute for Calligraphy, the National Institute for Music, and the National Association for Theatre, Music, and Folk Art, but these were agencies of restriction rather than facilitators of cultural experiment. In the 1980s there was a ban on Western musical instruments, which were deemed to spoil the sensibilities of pure Jamahiriya society. The Committee for Theatre dictated which plays were to be staged. In film, there was a National Cinematographic Organization and a State Organization for the Production of Feature Films. The regime financed several propaganda films (produced abroad) on the Libyan resistance against the Italians, such as Omar Mukhtar: Lion of the Desert (1981), a film about Omar Mukhtar starring Anthony Quinn as Omar and Oliver Reed as the Italian general Rodolfo Graziani. It was directed by Syrian filmmaker Moustapha Akkad, who also directed Mohammad, Messenger of God (European title; US title The Message, 1976) chronicling the birth of Islam, which was funded by the Saudi and Libyan governments. He also produced the American slasher movie Halloween (1978) and seven sequels.

Sometimes these state-sponsored bodies did great work beyond their immediate briefs. One such was The Institute for the Study of the Jihad of the Libyans against the Italian Invasion, established in 1977. Muhammad Jarari, its director, described himself as ‘a person who trained to run across minefields. I had to manipulate the patronage system of Gaddafi’s rule to succeed in promoting scientific historical research’. His centre built an impressive archive of Libyan history, including an oral history project that amassed 10,000 interviews with Libyan participants in the struggle against the Italians and several million documents concerning Libya’s 20th-century history, including collections of photographs, newspapers, and personal correspondence of prominent Libyans. These have all survived the war, although the centre has been renamed the Libyan Centre for Manuscripts and Historical Studies (al-Markaz al-Libi li-al-Makhtutat wa-al-Dirasat al-Tarikhiya).

The Libyan writer most famous in the West was a clear opponent of the regime. Hisham Matar was educated in London and writes in English. He was born in 1970 in New York City, where his father worked for the Libyan delegation to the UN. He returned to Libya at the age of three and spent his early childhood there. In 1979 the regime accused his father of being a reactionary, and the family fled to Egypt, where his father worked among the exiled community against the regime. In 1986 Matar moved to London to study architecture and design. In 1990, his father was kidnapped in Cairo and transported to Libya and has never been traced, although he was reportedly alive in Abu Salim prison in 2002. Hisham Matar’s two novels, In the Country of Men and Anatomy of a Disappearance, are based on these events. In the Country of Men was shortlisted for the 2006 Man Booker Prize and won the 2007 Commonwealth First Book Award for Europe and South Asia, the 2007 Royal Society of Literature Ondaatje Prize, the Italian Premio Vallombrosa Gregor von Rezzori, the Italian Premio Internazionale Flaiano (Sezione Letteratura), and the inaugural Arab American National Museum Book Award. It has been translated into many languages. He lives in London.

Post-revolutionary culture

In post-revolutionary Libyan film, documentary and short movies have become particularly popular, perhaps because of the role Internet technology and social media played in the revolts. The Third Arab Screen Independent Film Festival (ASIFF), in Benghazi in February 2013 screened about sixty productions from across the Arab world. Co-winner for the best documentary was The Thousand Mile Road (directed by Murad Gargoum), which was filmed and edited in February 2011, before the fall of the Katiba military barracks in Benghazi. It was taken to Egypt by an Egyptian shuttle-bus driver. The prize for best Libyan film went to The Road to Bab Al Azizia (directed by Faraj al-Firjani and Ali Delax), which is about failed attempts to overthrow the Gaddafi regime in the early 1980s.

Among the other Libyan films that won prizes were:

- A Woman from Benghazi (directed by Tariq Mahyous), about a woman who took it upon herself to clean the streets around Freedom Square.

- The Return of a Flag (directed by Mohamed al-Theeb), about the return of the royalist tricolored flag as the flag of the revolution.

The Tripoli International Poetry Festival in April 2012 had sessions directly relevant to the revolution and wider aspects of the Arab Spring: Poetry in an Era of Great Transformation; Poetry in the World of Digital Globalization; and Place, Exile and Poetic Innovation.

As an indication of the extent of the cultural explosion in the aftermath of the fall of Gaddafi, the activities for one month, April 2013, included:

- The Tripoli Book Fair, a huge second-hand book fair, which its organizers claimed to be the largest cultural event in Libya.

- The inauguration of Benghazi as the Libyan Capital of Culture, with a carnival.

- The first First Zaala Festival for Tebu Heritage and Culture, in Murzuq (‘Zaala’ is Tebu for ‘Fezzan’).

- The Libya Movie Awards, which gave awards to the ten best short movies.

Local festivals are held annually in: March Germa, Hun, and Nalut; April Kabaw August Zuwara (the Awussu festival); October Ghadames (the old town); and December Ghat (the Akakus festival).

Music and Dance

The Libyan music industry is dwarfed by that of neighbouring Egypt. Egyptian singers such as the late Umm Kulthum, the great classical singer who died in 1975, are still extremely popular. There is a story that the 1969 coup was actually postponed by a day in order not to disturb her concert in Benghazi. Among modern Libyan singers are Mohammed Hassan, Mohammed Sanini, and Salmin Zarou. Traditional music from Murzuq, called murzqawi, forms the basis of many Libyan songs. Nowadays, it is often played on the accordion before wedding celebrations. Another genre popular at weddings is maaluf, from Andalusia, in which a group sings or recites poems of religious character or about love.

Television programs such as Lebanese Star Academy and Super Star have been closely followed for several years, contributing to the emergence of new talent. In 2004 the Libyan Ayman al-Aatar won the Lebanese Super Star. When new rounds of Star Academy were held in the Corinthia Bab Africa Hotel in Tripoli, 400 people volunteered for the auditions.

Museums

Not surprisingly, in view of Libya’s important Greek and Roman classical antiquities, there are numerous museums in Libya at most of the major classical archaeological sites, for example the Apollonia Museum (at Susa), Cyrene, Leptis Magna, the Punic Museum of Sabratha, and Tolmeitha. The Islamic period is covered by the Islamic Museum of Tripoli and the Karamanly House Museum (also in Tripoli). Most of the major towns and cities have local museums – Bayda, Benghazi, Derna, Zliten, Ghadames, and Janzur.

Tripoli has many museums, including ones specializing in epigraphy, ethnography, natural history, and prehistory, as well as the Red Castle Museum. There is a military museum at Tobruk.

The modern art of Libya is on display at the Dar al-Founoun in Tripoli, a complex established in 1993 by Ali Ramadan. The building was formerly the French embassy. The complex includes painters such as Ali al-Albani from Tarhuna, who paints contemporary landscapes. Ali Zwaik (Ezouik) and Ramadan Abu Ras are known for their abstract paintings and Ataf al-Somali for her watercolours.

Mohamed Zwawi (1936-2011) was a famous Libyan cartoonist born in Benghazi. He drew cartoons for both the pre-Gaddafi and the Gaddafi-era press, specializing in political and acerbic social cartoons. He died in June 2011, and his funeral in Tripoli was widely attended.

Food

Libyan restaurants do not have a good reputation; better food can be found in people’s houses. Libyan cuisine is a mosaic of historical influences: Mediterranean, Turkish, Muslim Spanish, and North African influences were supplemented by European cuisine in the colonial period: Turkish coffee is offered alongside North African mint tea and Italian espresso and cappuccino.

Among local dishes are couscous and tagine in many variants, osban (sheep’s stomach stuffed with rice, herbs, liver, and kidneys), lamb stews, grilled meats, shorba Arabiya (spicy Libyan soup with mint), bureek (stuffed filo pastry snacks), and stuffed vine leaves, eggplant, and other vegetables. Typical breakfast dishes are zummita (roasted wheat flour with cumin) and bsisa (various ground roasted grains, chickpeas, and fenugreek seeds mixed with oil into a peanut-butter-like consistency).

Pasta was added to the Libyan menu during the Italian domination. The most delicious is handmade pasta from water and flour. The Libyans eat lentils, chickpeas, spicy herbs, and vegetables. Libyans also have an extensive tradition of making lusa and harissa, Libyan spiced peppers, which are used to season dishes.

Sports

Football is one of the most popular sports in Libya. The first national league includes a number of teams. Tripoli and Benghazi are the home of many clubs. Al-Ahly won several league titles in Tripoli since the 1960s. The national team was prevented from participating in international competitions during the period in which the United Nations imposed embargo on Libya between 1992 and 1998. However, the team returned in the spring of 1999 to participate in world football activities with a friendly match against Senegal. In October 2020, Libyan’s national football team ranked 102 in FIFA’s world ranking table.

Horse racing is a traditional part of festive celebrations in Libya, while motor racing is also well-watched sport. Among the sports that Libyans enjoy are tennis and water sports. For the first time, Libya participated in the Olympic Games in the 1968 edition in Mexico.

Latest Articles

Below are the latest articles by acclaimed journalists and academics concerning the topic ‘Culture’ and ‘Libya’. These articles are posted in this country file or elsewhere on our website: