Introduction

After Mussolini’s regime in Italy embarked on a final ‘pacification’ of Libya, it abandoned even the semblance of collaborating with Libyan leaderships. It broke agreements with local leaders and, in 1922, Muhammad Idris, the Amir of Cyrenaica, went into exile in Egypt.

The Italian fascist government resolved to conquer the whole of Libya by force and by 1926 they had around 20,000 troops there. They used bombs and poison gas to subdue the population. In 1928 the remaining Sanusi leadership in Cyrenaica surrendered and the following year two northern provinces were united, with Tripoli as the capital under a fascist governor, Marshal Pietro Badoglio. However, Sanusi resistance continued under the leadership of a local shaykh, Umar al-Mukhtar.

Umar al-Mukhtar (1858 – 1931)

Umar al-Mukhtar, a Sanusi shaykh, was probably born in 1862 or 1858 in the Jabal al-Akhdar in Cyrenaica. He had trained as a religious scholar and teacher in al-Jaghbub. He became a Koran teacher and then fought against European colonialism. First, he opposed the French advance across the Sahara into Chad between 1900 and 1902. Then he joined the initial Sanusi resistance to the Italian occupation of Cyrenaica in 1911. During the First World War, he supported the Ottoman Empire by attacking British forces in Egypt.

Umar al-Mukhtar was a consistent opponent of all European control over Muslim territory and when Italian forces began to penetrate deep into Cyrenaica, he used his local knowledge to organize a highly successful guerrilla resistance by uniting the different tribes of Cyrenaica. Although his men were less well equipped than the Italians, they repeatedly beat them in action. The resistance continued until 1931 when the Italian army captured its now elderly leader (Umar al-Mukhtar was 73 years old), tried him for treason and hanged him in a concentration camp in front of 20,000 prisoners. After independence, he became a national hero. When redesigning the currency notes after the 1969 coup, Qaddafi opted to use a portrait of Umar al-Mukhtar, rather than his own image.

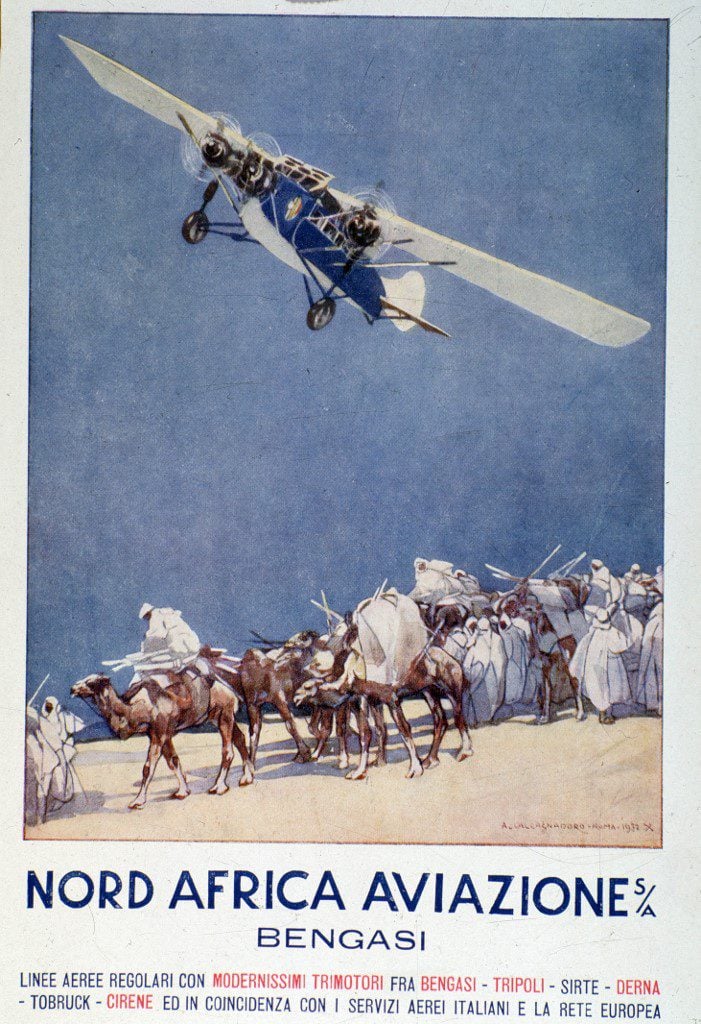

Italian Colonisation in Libya

After the reconquest was over, the Italian government made a further set of boundary agreements with French-controlled West Africa and British-controlled Egypt. But the agreement with France over the Aouzou Strip was never finally ratified, laying the ground for war between Chad and Libya in the 1980s.

Although Italian colonisation laid the basis of Libya as a national entity, the cost to the Libyan people was enormous. The conquest itself was bloody and has been called genocidal. To defeat Umar al-Mukhtar, two-thirds of the population of eastern Libya were imprisoned in concentration camps and at least 40,000 died. The Italian army built a barbed wire fence all the way from the coast to Jaghbub to stop reinforcements and supplies from Egypt. Kufra was bombed with poison gas.

Outside the war zone, the Italian administration made all uncultivated land public property, available to be settled by colonists. This included pasture land the local people used for their flocks. Most livestock was killed. Despite the plans, the full number of colonial settlers never arrived before the Second World War. The Italian colonial system provided virtually no education for Libyans beyond a primitive and restricted primary level.

Sources disagree on the numbers (and the baselines) measuring a clear demographic catastrophe for the native population: a drop from 1.4 million in 1907 to 1.2 million in 1912 to 825,000 in 1933 according to one source, a third of the adult male population between 1922 and 1931 according to another; yet another estimated that nearly half the Libyan population died between 1911 and 1933.

Part of the population loss resulted from people fleeing the colony. There were two large waves of emigration. Immediately after the Italian invasion of 1911, poorer people and nomads fled from Tripolitania to French-ruled Tunisia and from Cyrenaica to Egypt. During the fascist “Reconquista”, people from Tripolitanian tribes went not only to Tunisia, where they were employed in mining, but also to Egypt, where they worked in agriculture. Some men from richer families also went to Egypt to study and work and they formed the first political organisations in exile. These raised funds to support the resistance in Cyrenaica and later formed associations that promoted Arab nationalism in Tripolitania. The traditional Sanusi leadership was also based in Egypt.

While the Italians attempted to build a settler colony, they had no success, apart from removing Libyans from any positions of power in the country. Yet they had little time to put their plans into effect. World War II led to their defeat by the British, during which battles raged across the Libyan desert.