The Sudanese national movement’s roots go back to the growth of the new social stratum linked to the economic development fostered by the colonial authority, in the services sector, in industry, and agriculture, and to the modern education system established by the British colonial administration.

In this regard, this new nationalist movement differs significantly from the Mahdist or tribal mutinies that depended only on either reviving or repeating the Mahdia. The nationalist movement evolved in the cities and addressed the population there, with some echo in the rural areas, especially when religious leaders involved themselves in politics.

The traditional sectors of society—those that collaborated with the colonial administration in the native administration—allied themselves with the authorities against the emerging national movement aimed at liberation, looking at Egypt as an example and ally. The movement demanded the unity of the Nile valley under the Egyptian crown.

The first organization to be formed was the Sudanese unity Society, led by Ali Abd al-Latif, a Sudanese army officer jailed in 1921 as an agitator. In 1924, a new organization was formed, called the White Flag League, whose goal was to expel the British from the country. Demonstrations followed in Khartoum in June and August of that year but were suppressed.

When Sir Lee Stack, the governor-general, was assassinated in Cairo on 19 November 1924, the British forced the Egyptians to withdraw from Sudan and conquered a Sudanese battalion that mutinied the Egyptians’ support. The Sudanese revolt was ended, and British rule remained unchallenged until after the Second World War.

The long peace that reigned from 1924 ended in 1936 when the Anglo-Egyptian treaty was signed, allowed Egyptian officials to return. The educated Sudanese protested that Sudan’s future had not been negotiated and had not been consulted. In this atmosphere, the Graduate Congress was established, which remained the major Sudanese political body until the emergence of Sudanese political parties in 1946. The experience of the Indian Congress inspired the leaders of the Congress.

In the beginning, Congress confined itself to social and reform activities, but it gradually moved into politics. The administration refused, at first, to recognize the Congress as a representative body of the Sudanese. However, it did, in fact, take into consideration the wide support enjoyed by the organization.

There were two trends within the Congress—the moderate, the majority, and the radical. The moderates tended to cooperate with the authorities, while the radicals, led by Ismail al-Azhari, who would later be the first Sudanese prime minister, turned to Egypt. They rapidly gained support within and outside Congress. Azhari was able to dominate the Congress with the support of the Ashigga party, the first party to appear under the patronage of Sayyid Ali al-Mirghani, the leader of the Khatmiyya religious sect.

The moderates also formed their own party, the Umma Party, with Sayyid Abd al-Rahman al-Mahdi, the Mahdi and leader of the Ansar sect, to cooperate. With the British while pursuing independence, under the slogan “Sudan for the Sudanese.”

Side by side with the political movement, the trade union movement, led by the Sudan Railways workers, was influenced by the Sudan Communist Party; they were able to form a trade-union federation that gained official recognition. The farmers were also active and formed their own union under a leftist leadership and contributed much to the struggle against colonialism.

The colonial administration tried to present some constitutional transformation that would allow Sudanese participation in ruling the country, but it was too late. They proposed an advisory council for northern Sudan, composed of the governor-general and 28 Sudanese, but this council faced a boycott by the strong unionist movement and the Khatmiyya sect. While the Umma party and Ansar sect joined and supported the consultative council. The same fate faced the body known as the Legislative Assembly, which included the South Sudanese, a change from the British policy that sought initially to isolate the south.

In 1952, Egypt unilaterally abrogated the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty of 1936 and proclaimed Egyptian sovereignty over Sudan after a military coup led by Gamal Abdel Nasser overthrew the monarchy and took power. The new leaders were ready to reject the idea of sovereignty over Sudan and accept the country’s independence.

The Anglo-Egyptian treaty was signed in 1953, granting self-government and self-determination for the Sudanese within three years.

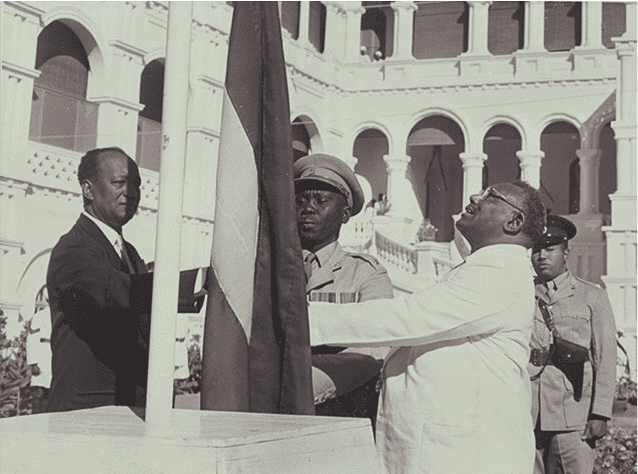

Elections for a representative parliament to rule Sudan followed in November-December 1953, resulting in a victory for Azhari, who – while his Unionist party was strongly pro-unity agreed to support the vote for independence in the parliament late in 1955. Sudan became independent in January 1956.