Introduction

Sudan’s first periodical, the Arabic-English Sudan Gazette, began publication in 1899. The British, who shared administrative authority over Sudan with Egypt, used the gazette to publicize new laws and official rulings.

Four years later came Sudan’s first private Arabic newspaper, Al-Sudan. Again, the publisher was an outsider, this time a Lebanese businessman who had previously established pro-government newspapers in Beirut and Cairo. In subsequent years, Sudan’s emerging press industry largely followed that pattern of foreign ownership (typically Lebanese, Egyptian, and European businessmen) and a pro-government stance.

During the first three decades of its history, the Sudanese press was routinely subjected to Ango-Egyptian censorship, particularly as the country began to chafe under its colonial rulers. Sudan adopted its first press regulation in 1930. Newspapers could not publish without a permit, which meant owners and editorial boards had to meet with government approval and all editions were subject to censorship by the Intelligence Department.

It was during this era of press restrictions that Sudan’s first daily newspaper, Al-Nil, made its debut in 1935. That was followed in 1940 by Sudan’s first radio broadcast, which aired from Omdurman for 30 minutes a day with updates on World War II. Yet gaps in technology and infrastructure delayed a national radio service for more than 30 years.

Sudan’s independence in 1955 unleashed a volatile era for the press, mirroring the country’s chronic political tumult. After the 1958 military coup, political parties and their newspapers were banned. In 1964, that decision was reversed.

Television broadcast arrived in Sudan in 1963, thanks to West German engineers and technology. Then in 1969, General Gaafar al-Nimiery seized power. The following year, he nationalized the press and banned all independent publications. A free press was not restored until 1985 when Nimiery himself was overthrown in a coup.

The parliamentary government that briefly followed Nimiery’s rule gave rise to a flurry of new publications. But censorship returned after Sudan’s third military coup, in 1989. On his first day in office, President Omar al-Bashir banned all publications except the Armed Forces Newspaper. He subsequently allowed a few military- or government-owned newspapers to operate as government mouthpieces.

In the 1990s, when the majority of Sudanese could not read or write, television and radio were the primary tools of mass communication. During Sudan’s second civil war, from 1983 to 2005, warring factions, such as the National Democratic Alliance and southern separatist movements such as the Sudan People’s Liberation Army operated covert radio stations. They broadcast into Sudanese airwaves from Eritrea and Ethiopia in order to circumvent censorship. Meanwhile, satellite dishes grew popular among wealthy Sudanese in the 1990s. Viewers got access to foreign broadcasts in exchange for an annual fee to the government.

The 1993 Press and Publications act loosened media restrictions and allowed “political” newspapers to resume publication with a government license. The gradual introduction of the internet during the second half of the 1990s broadened further broadened Sudanese citizens’ access to information. Nonetheless, the government maintained tight control over the media throughout the decade.

As the civil war worsened, President al-Bashir in 1999 declared a state of emergency that paved the way for greater government censorship over the media. That was partially lifted in 2001.

The signing of Sudan’s peace agreement in 2005 ushered in a more democratic period for the media. However, the country’s nascent independent press quickly found itself facing government intimidation, with 15 Sudanese and foreign journalists arrested in the first half of 2006. When South Sudan formally seceded in 2011, Sudanese media outlets once again found themselves under increasing government intervention amid the political unrest.

Little Freedom of Expression

It is no surprise, then, that Sudan’s media ranks as among the most repressive in the world Reporters Without Borders’ 2017 World Press Freedom Index puts Sudan at No. 174 out of 180 countries.

The 2005 Sudanese constitution ostensibly guarantees a free press. Article 39 says “The State shall guarantee the freedom of the press and other media as shall be regulated by law in a democratic society.”

But the article also stipulates that “All media shall abide by professional ethics, shall refrain from inciting religious, ethnic, racial or cultural hatred and shall not agitate for violence or war.” The subsequent 2009 Press and Publications Act also contains a vague references to religious or ethnic incitement.

The law is more explicit about the punishment: Banning publications deemed guilty and holding newspaper editors personally liable for everything they publish. The act also gives authorities the power to shut down newspapers for up to three days without a court order and to impose long-term suspensions. All journalists must register with a national press council, which is under direct supervision by President al-Bashir.

Sudanese journalists can face either criminal or civil defamation lawsuits, although such cases have been rare in recent years. Censorship is far more pervasive, with the National Intelligence and Security Service routinely issuing directives to editors and temporarily shuttering media outlets that do not comply.

The 2010 National Security Act codified immunity for authorities who arrest and censor the media in the name of national security. During the 2015 national election, the National Intelligence and Security Service seized entire print runs of several newspapers, including Al-Mijhar and Al-Some Sudanese journalists have faced criminal charges after falling afoul of government repression. Notable cases include the December 2015 arrests of two newspaper editors, Osman Mirghani of Al-Tayar and Ahmed Yousef al-Tay of Al-Saiha. Both newspapers criticized Sudan’s frequent electricity cuts. Mirghani and al-Tay were charged with publishing false news and undermining the constitutional system. The latter offense is punishable by death. The two were eventually released on bail pending trial.

In March 2016, 30 Sudanese journalists went on a hunger strike in solidarity with Mirghani and al-Tay, protesting outside the offices of Al-Tayar. In April 2016, journalist Ahmed Zuheir Daoud was arrested after covering student protests at Khartoum University. Daoud was held without charge for more than a month, drawing international protests. So far there has been no confirmation of his release.

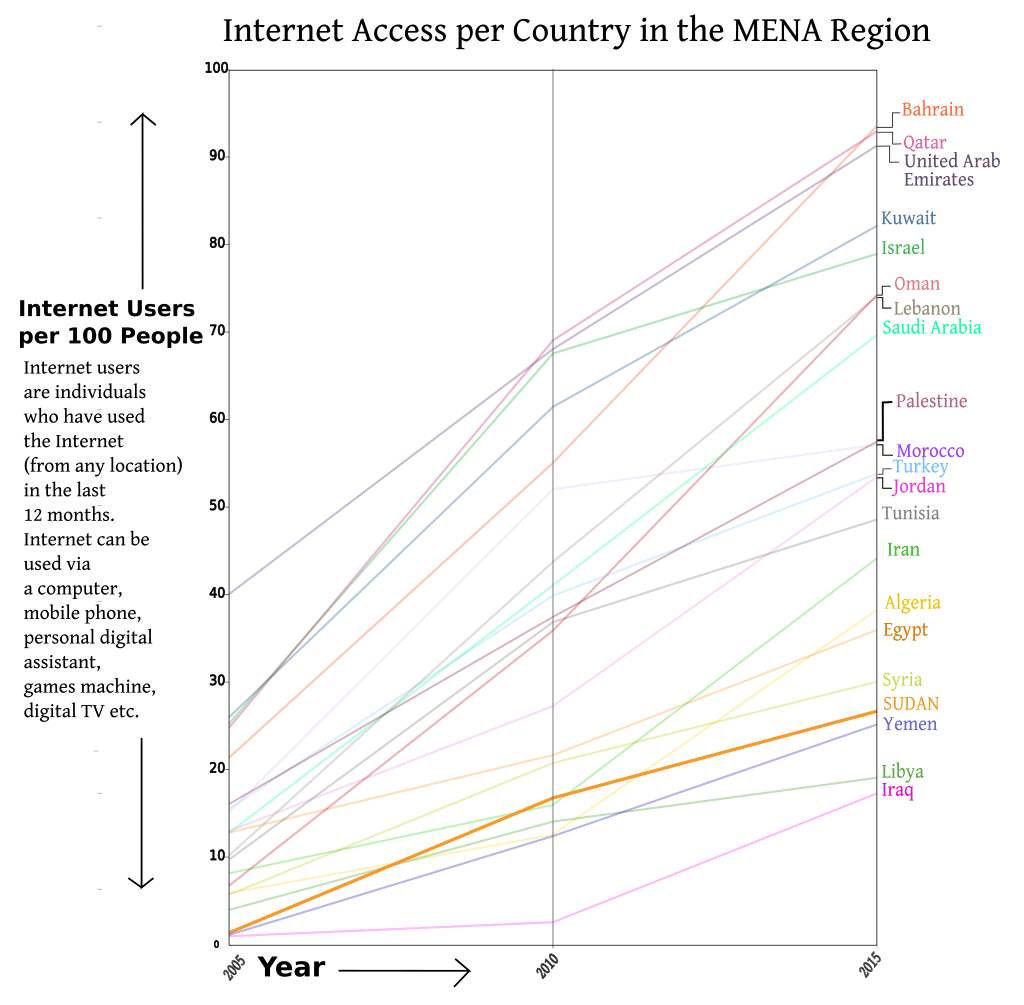

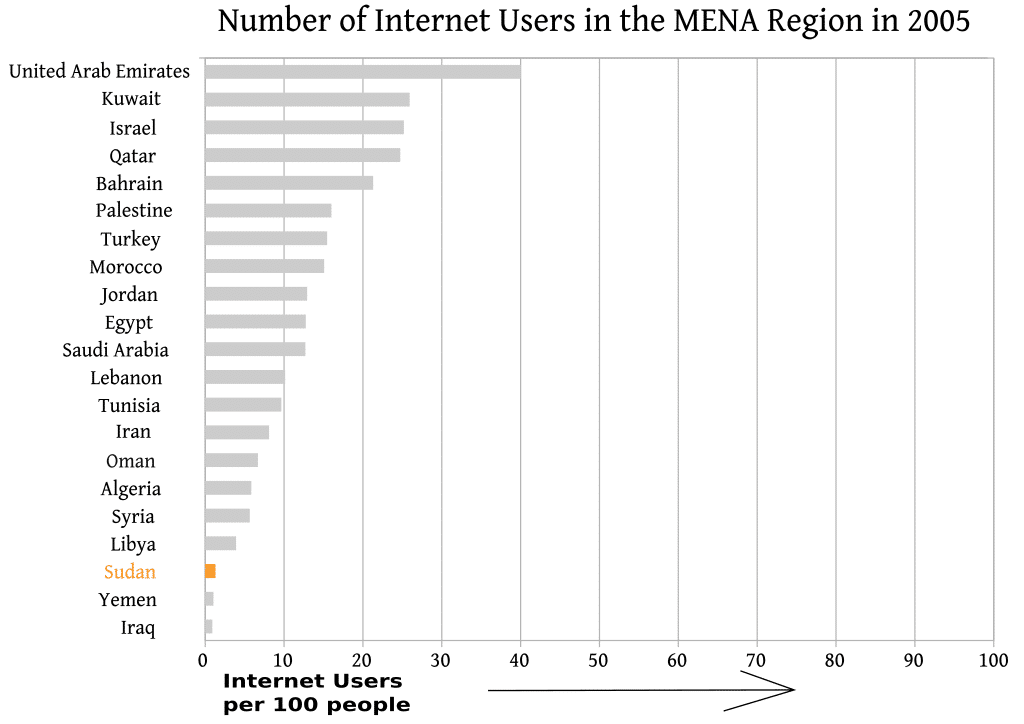

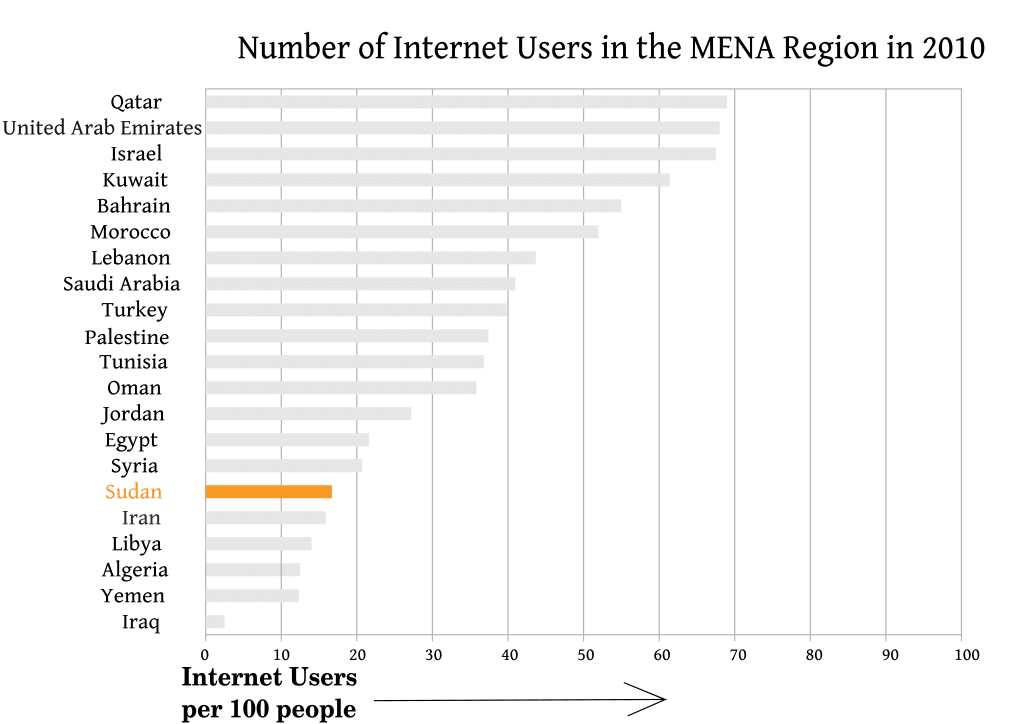

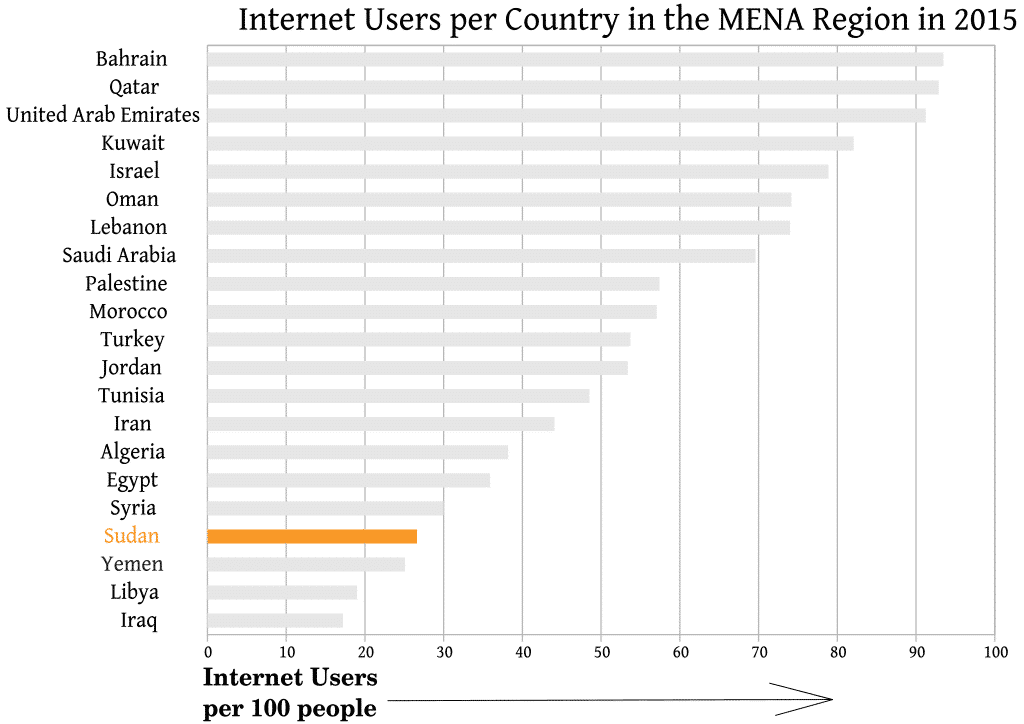

Sudan has a relatively low internet penetration. But authorities closely monitor and control online communications. An update to the 2009 Press and Publications Act, due to come into force later in 2017, proposes to create a specialized council to monitor social media activity. Sudan’s minister of information has warned that the legislation will be used to pursue anyone who spreads false news to discredit Sudan’s image.

Television

Television broadcasts in Sudan are monopolized by the Sudan Radio and Television Corporation, a government network founded in 2002. Private television channels are not officially outlawed, but the government’s grip over infrastructure and funding means few stations exist.

Some private channels have been granted the right to broadcast from outside the country. The most prominent channels are:

Sudan TV: Launched in 1963 as the country’s national television network, with colour broadcasts first appearing in 1976. The channel airs a variety of entertainment, educational, and news programming.

Blue Nile Channel: Established in 2006 ostensibly as a public/private enterprise, however the owners are closely affiliated with President al-Bashir and it is largely government funded. The channel mainly broadcasts entertainment and cultural programming, and avoids overly political content. In February 2017 the channel’s offices were severely damaged by a fire.

Ashorooq TV: Established in 2006 as a private Sudanese channel that broadcasts out of Dubai Media City in the UAE. It is government-approved and airs news and entertainment programs.

Omdurman TV: Founded in 2010 as a private channel based in Sudan. In November 2016 it was ordered to close by the Sudanese government, allegedly because it did not have a proper permit. The channel had recently aired critical coverage of austerity measures in the country.

Radio

Radio is the most ubiquitous medium in Sudan because it can reach far rural areas and costs relatively little to broadcast. By 2007 18 of Sudan’s then 26 states were within reach of regional radio stations. National stations, both public and private, broadcast mainly out of Khartoum or Omdurman. The government retains at least a 15 percent stake in all radio channels. The most popular national stations include:

State-owned:

Sudan Radio: State radio station established from the foundations of the World War II broadcast service in Omdurman that was renamed “Sudan Radio” after the country achieved independence. The station now broadcasts for 24 hours per day and serves as a primary propaganda outlet for the Sudanese government.

Holy Qur’an Radio: National station founded in 1970 that offers 24-hour religious programming.

Sudanese Home Service: A station dedicated to Sudanese culture and family affairs.

European Service: Radio station that offers programming in English and French to cater for non-native listeners.

Privately-owned:

Most commercial channels tend to air music and entertainment programming, such as the popular Mango 96 FM and avoid material that would likely attract censorship. One exception is Khartoum FM, which is owned by the former Minister of Finance Abdel Rahim Hamdi and serves as a talk show discussing economic issues from a pro-government stance.

A number of international organizations have established unsanctioned radio stations in Sudan in recent years. The effort is meant to bring information to vulnerable or conflict-ridden areas, such as Darfur or the border between Sudan and South Sudan. Radio Dabanga was established in 2008 as a shortwave station broadcasting to the Darfur region, in cooperation with Dutch nonprofit group Free Press Unlimited. In 2011, after South Sudan’s succession, the group also founded Radio Tamazuj to provide the “marginalized border region” with what it called nonpartisan news on both countries.

Press

Sudanese newspaper readership statistics are difficult to obtain. A 2006 report by the National Press Council estimated total daily circulation at 292,700 – at a time when the country had a population of nearly 33 million people. As with television and radio, all newspaper content must be cleared by government censors. Since press ownership rules were democratized after the peace deal, the government has begun establishing shell companies to buy stakes in independent newspapers. Indeed, as, much as 90 percent of “independent” publications in Sudan in 2013 were reportedly owned by Khartoum.

The most popular daily publications include privately-owned Al-Rai al-Aam, one of Sudan’s oldest and most influential newspapers, which was first published in 1948., Another is Al-Sahafa, which was founded in 1961 as a private daily, but which was sold to Sudan’s security agency in 2013. Other privately-owned, pro-government newspapers include the semi-independent Akhbar al-Youm and Al-Khartoum.

Some newspapers have dared to adopt a more critical stance toward the government. They include Al-Watan and Al-Tayar, both of which have been suspended temporarily and have whole editions confiscated by the intelligence and security service. Al-Tayar was closed between 2012 and 2014 for criticizing the government’s surveillance of opposition parties. In 2015, it was suspended again, this time for opposing cuts to fuel subsidies.

In February 2015, the print runs of Al-Watan, Al-Tayar, Akhbar al-Youm and 11 other dailies were seized by authorities without explanation. Al-Jareeda, the licensed newspaper of the government opposition, is a particularly frequent target of government intimidation. Eight of the newspaper’s print runs were seized over a period of three weeks in December 2016, without warning and without an explanation.

Online Publications

During the first decade of the 21st Century, online news outlets in Sudan were free to operate with relatively few restrictions. But that has begun changing as the government stepped up its surveillance over digital journalism. Websites that are considered “immoral” or “blasphemous” are blocked by Sudanese internet service providers. Still only a few politically orientated websites are actively filtered. Consequently, the internet remains a crucial platform for independent news outlets.

Waleed al-Dood Miki al-Hussein, a Sudanese citizen living in Saudi Arabia, launched Al-Rakoba in 2005. The online newspaper publishes news and opinion pieces from a variety of Sudanese and international contributors. The website was closed down several times by Sudanese authorities. In July 2015 al-Dood was arrested without a formal charge. He was released in February 2016 with no further action against him or the website.

Hurriyat Sudan, a seven-year-old online newspaper, had its website blocked by the government during protests at the University of Khartoum in 2012. The editor-in-chief at the time, Elhag Warrag, referred to the blockade as “part of a systematic attempt by the Sudanese regime to stop news about anti-government demonstrations reaching the Sudanese people. “

The government’s attempts at censorship have sometimes backfired. When several independent journalists were unable to obtain government accreditation, they migrated their work to Al-Taghir. The website since then has grown to become a relatively outspoken outlet for news.

Finally, Radio Dabanga, the station founded by a Dutch nonprofit, also hosts a sister news website that is often critical of the Sudanese government.

Latest Articles

Below are the latest articles by acclaimed journalists and academics concerning the topic ‘Media’ and ‘Sudan’. These articles are posted in this country file or elsewhere on our website:

Social Media

Only about a quarter of Sudan’s people have access to the internet. So it is difficult to gauge the impact of social media. Nevertheless, a number of online campaigns have taken off in recent years, and more Sudanese are speaking their minds on social media.

In 2016, for instance, Khalid al-Wazir, a talk show host on Blue Nile TV, sparked widespread outrage after referring to Ethiopian domestic workers in a “racially insensitive” language. Critics soon put up a Facebook page and created hashtags to demand an apology. The campaign attracted traditional media coverage, and Al-Wazir quickly apologized.

Another social media campaign was launched in November 2016 by Sudan Change Now, a group of activists who originally banded to protest the subsidy cuts. The group urged citizens to go on “strike” by staying home. Many people heeded the call, closing down businesses and schools in Khartoum. The following month, the campaign pulled off a successful boycott on government transactions. A defiant President al-Bashir declared that his “regime will not be overthrown by keyboards.” It is clear, however, that online mobilization is producing results.

The Sudanese government has responded by stepping up reprisals against its critics on social media., Khartoum is increasingly using leaked WhatsApp messages as evidence in cybercrime and libel cases. Facebook posts have also been targeted. Ibrahim Baggal, a Facebook user who criticized the governor of North Darfur in February 2016, found himself detained for 55 days.