Introduction

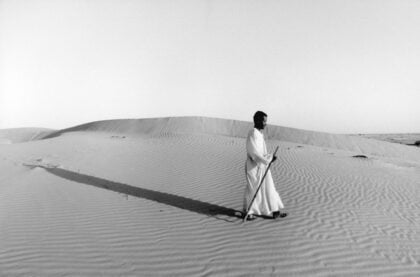

Sudan is characterized by diversity. Many families, clans, and tribes claim genealogies that can be traced back generations to Arab origins. Yet the complexity of ethnicities indicates genetic and cultural intermingling that goes back much further.

Islam is an integral part of Sudan’s social fabric and media landscape as well as a politically mobilizing and polarizing force. However, other socio-economic and cultural factors play various interlinked roles in shaping the country.

Rural communities are characterized by traditional tribal and ethnic social structures and subcultures. Modern large-scale agricultural projects, such as the Gezira irrigation scheme, attract laborers from all over the country, forming a sort of national melting pot, especially in and around the capital Khartoum.

Women in Sudan: Strong Presence in Public Life Amid Growing Restrictions

Women in Sudan have a strong presence in public life. They represent a large proportion of civil servants and students in educational institutions. They also have a prominent role in social, political, and cultural activities. However, they face many constraints because of local values and norms and state laws that have become increasingly incompatible with women’s aspirations for equality and freedom since Islamists seized power in 1989.

Women had powerful positions going back to the Nubian kingdoms before Islam and Christianity. Some of the queens of that time were Amanji Renas, Shankid Khito, and Amani Shakhito.

The first school for girls was opened in 1907 in the city of Rafaa, south of the capital Khartoum. The women’s movement began to form in the first half of the 20th century, leading to the formation of the Sudanese Women’s Union in 1952, which demanded women’s political and social rights. According to government statistics, in 2008 there were more than 700 women’s organizations in Sudan. The ‘No to Women’s Oppression’ initiative is the most active women’s organization in Sudan today.

First Female Parliamentarian Elected in Africa

Sudanese women have been pioneering in many fields in Africa and the Arab world. The first women’s newspaper was published in 1955. Since the first parliamentary elections in 1953, women have had the right to vote, and there have been female doctors, media activists, and political leaders. One of them was Fatima Ahmed Ibrahim, who in 1965 was elected the first deputy parliamentarian in Africa and the Middle East. By the late 1960s, Sudanese women had the right to participate in all areas of employment and earned equal opportunities for rehabilitation, training, and promotion. They also had the right to equal pay for equal work and were included in the pension system.

In 1971, Nafisa Ahmed El-Amin became the first female Sudanese minister. Currently, there are seven female members of the 48-member Federal Council of Ministers. The proportion of female teachers is 69 percent, female lawyers 41 percent, female police officers 10 percent, and female students 51 percent. There are 78 female members of parliament out of 354. Sudanese election law provides for the allocation of a quota of 30 percent of seats in the Central Legislative Council and the Council of States through separate electoral lists for female candidates.

Writer Dawaja al-Awni said, “The prominent role played by Sudanese women in a traditionally conservative society is paradoxical for everyone who has visited Sudan.” She believed that “the liberal character of women in Sudan has not been created by chance, but the result of a social advantage that has been characteristic of Sudanese men and women because of the African influences that made them more spontaneous, both physically and behaviourally.” She also attributed this to the prominent Sufi culture in Sudan, characterized by a popular, simple, tolerant strain of Islam that treats both genders equally.

Female Genital Mutilation

Despite these tolerant values, women have faced many difficulties and forms of discrimination, oppression, and violence, most notably female genital mutilation (FGM), which has been practiced for hundreds of years.

Sudanese legislation criminalized female genital mutilation in 1947, but the previous Penal Code of 1983 and the 1991 Penal Code currently in force made no reference to the criminalization of this practice. Despite public and official efforts to combat FGM, it is still prevalent, especially in the countryside. Government statistics in 2016 indicated that FGM had decreased to 31.5 percent among girls under 14 years of age. An official statement by the director of the National Project to Combat Female Genital Mutilation in Sudan said that the rate of women circumcision at the national level is 65.5 percent. Circumcised women are exposed to many problems, including extreme pain and complications – some of them fatal – during childbirth.

New Restrictions

When the Islamists seized power in 1989, official and community restrictions were imposed on women under the pretext of ‘Islamic fundamentalism’ and the implementation of the ‘civilizational project’ to reshape Sudanese life.

Local wars under the so-called ‘salvation government’, particularly the Darfur war, saw a series of mass rapes of women. Most of these crimes were committed by government-backed Janjaweed militias, some of whom were regular soldiers.

In urban areas, women faced arrest, imprisonment, whipping, and fines on several charges related to personal conduct or clothing, and sometimes because they were seen in public with men who were not legally related to them.

The campaigns were later legalized as public order laws, which include provisions stipulated in the 1991 Penal Code, and a law called the Khartoum Public Order Act of 1996. The laws criminalized a wide range of personal behaviors and include what are described as ‘obscene acts or materials’, ‘indecent clothing’, ‘seduction’, ‘debauchery’, ‘obscene acts in public’, and ‘immoral songs’. Because of the loose definitions of these behaviors, their interpretation was left to individual police officers. Women were the most affected and targeted group, and they were taken to police departments and courts in large numbers, whether as individuals or groups. Some policemen saw in these laws an opportunity for financial and sexual blackmail and, in some cases, sexual favors in return for the women’s release.

According to statements by the Ummah Party leader Mariam al-Mahdi, published in late 2010, 40,000 women were whipped in one year under the provisions issued in accordance with the public order laws.

One of the most recent cases involving the public order laws was the arrest of human rights activist Wini Omer on 30 December 2017 on charges of being indecently dressed while wearing a skirt, blouse and scarf and walking in an indecent manner. Although the court acquitted her, she was monitored by public order officers and was the target of a security crackdown in February 2018. A group of officers broke into a house where she was meeting some friends, all of whom were accused of prostitution, drinking alcohol, and drug abuse. Subsequent examination of the defendants proved that they had not used any alcohol or drugs.

Women also face other forms of discrimination concerning their rights and duties under the Personal Status Law, which is derived from Sharia law. The law stipulates that a guardian is the one who marries off a girl, and the law entitles the guardian to annul the marriage contract if an adult and rational woman is married without his consent. It also stipulates that a woman shall be denied the right to maintenance on divorce if she disobeys her husband and that the testimony of two women shall be equal to that of one man. The law also gives a husband the exclusive right to divorce. Moreover, it makes it a condition for a wife to give compensation if she agrees with her husband on khul (divorce initiated by the wife ). This law is also flawed because it does not specify a minimum age for marriage, and it gives guardians the right to marry off girls who are over ten years of age, with a judge’s permission.

Marital Rape

In May 2018, a Sudanese court sentenced a 19-year-old girl to death for murdering her husband after he tried to rape her. According to Noura Hussein, her father forced her to marry her cousin at the age of 16, and she refused to consummate the marriage on the wedding night. She said the next day, her husband got three of his male relatives to hold her down while he raped her. When her husband tried to rape her again the day after that, she resisted and stabbed him with a knife. After a large national and international solidarity campaign, the Court of Appeal in June reduced the death sentence to five years’ imprisonment.

Challenging Clerics

In September 2018, an episode of the television program Youth Talk presented by the German public broadcaster Deutsche Welle, entitled ‘What Do Sudanese Women Want Today?’, caused an uproar in Sudan because of the intense dialogue between Sheikh Mohammed Osman Saleh, head of the Association of Sudanese Scholars, and women who advocated women’s rights and their personal and public freedoms. A comment by a 28-year-old woman called Wiam Shawqi was one of the most controversial. She attacked Sheikh Saleh for saying that “illegal” dress worn by women encourages harassment and for his support for the marriage of underage girls. Shawqi called for women’s personal freedoms, equality in family rights, and a wife’s right to unilateral divorce.

Mosque imams and a large number of young people on social media sites criticized the German channel and the program and accused them of spreading corruption, infidelity, atheism, and secularism in Sudan. They also denounced Wiam Shawqi for her lack of manners and undermining the constants of religion. Some hardliners threatened to attack the channel Sudania 24, which linked up with Deutsche Welle to record the episode in Khartoum.

It is worth mentioning that the Sudanese government has refused to sign the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) since its inception in 1979. Sudan currently ranks 165th out of 188 countries on the Gender Inequality Index.

Clans and Communities

A multitude of ethnic groups, languages, and religions coexist in Sudan. The country is divided into two major ethnic groups: Arab and African. Ethnic communities are divided into several tribes. Arab tribes live mostly in the center of the country and to a lesser extent in the west; African tribes are concentrated in the far north, the Nuba Mountains, the Southern Blue Nile, the east, and Darfur in the west.

Traditional life centers around the tribe, which represents one of the most important forms of social organization. A great deal of the local economy, politics, and social life is organized or influenced by tribal traditions and norms. For example, in pastoral communities, the land is usually owned by the tribe rather than individuals and land use rights are negotiated between tribes. Tribal influence is a decisive factor even in representation in modern governmental institutions, such as national and regional parliaments. In rural areas, only candidates with strong tribal support win elections.

The majority of the population is Muslim. This is especially obvious in South Sudan, where 97% of the population adheres to Islam. Tolerant Sufism is the dominant form of Islam but it is far from homogenous. Following independence, the two largest Islamic sects, Khatmiyya and Ansar, gave birth to Sudan’s main political parties, the National Unionist Party (later the Democratic Unionist Party) and the Umma Party, paving the way for future divisive religious politics.

More recently, relatively radical Islamic movements have emerged, demanding the establishment of an Islamic state that enforces sharia law. These movements, particularly the Muslim Brotherhood, which has used various names throughout its history in Sudan, have posed a threat to the traditional religious sects and played a more important role in Sudanese culture. The traditional religious sects, and their associated political parties, built their legitimacy on traditional Sunni Islam.

The Muslim Brotherhood introduced a more modernist religious approach, with strong influence among the urban educated population, better organizational skills, and a powerful media and propaganda machine coupled with regional support outside Sudan. Thus, the Muslim Brotherhood has gradually managed to confine the traditional sectarian parties to rural areas.

Youth

Young people make up 62% of the total population and the majority lives in poverty. One-third of young women and a quarter of young men aged 15-24 are illiterate. Around half of young men and women have completed primary school, which indicates a high dropout rate. Admission to secondary schools and higher education is still low, especially in rural areas.

Young people who struggle to access education also have difficulty finding work. Overall, 20% of Sudanese youth are unemployed; the percentage of unemployed young women is even higher. This has led to mounting frustration.

Even those who find employment in the informal sector work long hours for low wages and without social protection. Young people are also particularly at risk from drug use and exposure to sexually transmitted diseases.

The civil war that began in 1983 and is ongoing in several regions, has taken its toll. For many young people, migration is seen as the only way out.

Yet despite making up the majority of the population, youth participation in Sudan’s political and social life is limited. A number of governmental and non-governmental <a href=”https://fanack.com/wp-content/uploads/Giving-Young-People-a-Priority.pdf”>programmes</a> have been established to target and resolve youth issues.

Education

Sudan’s pre-independence public education system was designed by the colonial power to produce civil servants and professionals. Post-independence, the system underwent many changes, aimed at meeting the country’s dynamic economic and social needs. Today, education in Sudan is free and compulsory for children aged six to 13. Primary education lasts eight years, followed by three years of secondary school. Students can choose between two academic tracks: scientific-literary and technical (agricultural-industrial-commercial).

The language of education at all levels is Arabic. Schools are concentrated in urban areas. Primary school enrollment in 2001 was estimated by the World Bank at 46% of eligible students and 21% of eligible secondary school students. Enrollment varies widely, falling below 20% in some provinces.

Besides public education, Egyptian educational missions and missionary schools have contributed a great deal to education in Sudan, with activities extending to a number of provinces.

Private education at primary and secondary levels was introduced in the 1950s and spread quickly after the deterioration in public education. Although there are no exact figures, there are known to be several expensive and prestigious private schools in Khartoum, accommodating pupils from upper-class families and teaching in English.

Higher education emerged in 1902 with the establishment of Gordon Memorial College. It changed its name to the Khartoum University College and broke away from the University of London in 1956, becoming the University of Khartoum.

Before independence, several educational institutions were established to award diplomas to government employees who had completed secondary school. One of these was the Khartoum Technical Institute, the leading center of technical education in Sudan. It became the Khartoum Polytechnic Institute in 1975 and was given university status in 1990, becoming the Sudan University of Science and Technology.

Cairo University (Khartoum Branch) was established in 1955 and renamed Al-Neelain University in 1993. In 1975, the universities of Juba and Gezira were established.

After the ‘revolution of higher education’ of 1990, the number of government universities jumped from five to 35 in 2010. At the same time, higher education became a field of private investments and tens of private universities and colleges were opened in all parts of the country, with a noticeable concentration in Khartoum. The number of private universities and colleges is now estimated to be around 61. This tremendous upsurge resulted in a shocking drop in government expenditure on public education, accounting for only 1% in 2010 and 2% in 2011.

The rapid expansion of higher education institutions was accompanied by a marked deterioration in the quality of the education provided, and some 45% of graduates is unemployed.

Health

The Ministry of Health provides health services in cooperation with the private sector and through other health sub-systems and health care organizations. These bodies organize health care on three levels: the public sector, National Health Insurance Fund which contributes to health financing and has its own private health facilities, and the private sector which is growing rapidly in major cities, with a focus on curative care.

According to official figures, there are 366 government hospitals of various capacities and another 185 hospitals owned by the private sector as well as more than 1,400 health care centres. The ratio of doctors per 100,000 citizens is 86. The same figures state that only 45.9% of the population benefits from health insurance services. Despite the fact that the number of health facilities in Sudan has grown significantly over the last ten years, privatization policies is making it difficult for more people, especially in rural areas, to access proper health care.

The funding system is based on user fees along with social solidarity programs. The social health insurance system was introduced in 1995, coinciding with the private sector expansion. However, the health insurance system is concentrated in urban and semi-urban areas. Millions of rural residents, particularly in areas affected by war, are not covered by the health insurance network. In 2006, free emergency care for the first 24 hours was introduced and, in 2008, financial support for pregnant women and children under the age of five became available.

Even so, maternal and child mortality rates in 2013 were higher than previous years. Sudan is still to achieve the Millennium Development Goals of reducing child mortality and improving maternal health. Child malnutrition is a serious health challenge.

Sudan is home to a number of tropical and infectious diseases. Malaria is the most deadly and widespread due to the high temperatures and poor drainage infrastructure. Malaria poses a national health threat, with more than 1.5 million cases reported in 2010 alone. Yellow fever, hepatitis A and typhoid are also common.

Latest Articles

Below are the latest articles by acclaimed journalists and academics concerning the topic ‘Society’ and ‘Sudan’. These articles are posted in this country file or elsewhere on our website: