In 1970s, the Arab-Israeli conflict became more and more intertwined with the Cold War. The Soviet Union strengthened its ties with (Nasserist) Egypt and (Baathist) Syria. In November 1971, Washington reached a memorandum of understanding with Israel, concerning military aid and coordination of policy. Both superpowers supplied the region with arms.

The political stalemate prompted Egypt’s President Anwar Sadat, who had succeeded Gamal Abdel Nasser after the death of the President in 1970, to look for other solutions. He tried to maintain closer ties with the United States. As a token of Egypt’s independence Sadat expelled thousands of Soviet military advisers in the summer of 1972 (although the country would continue to rely on the Soviet Union as its arms supplier for several years).

However, Washington did not respond to this gesture (the Americans were heavily involved in the Vietnam War, and American President Richard Nixon was in dire political straits at home). As a result, Sadat purportedly believed it necessary to challenge Israel militarily in order to bring the Americans into play.

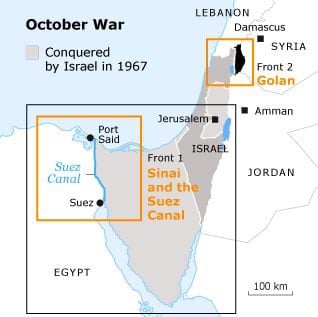

In order to disperse the Israeli forces, the Egyptian president turned to his Syrian counterpart, President Hafiz al-Assad. This coalition would force Israel to engage in a war on two fronts, in the Israeli occupied Sinai in the south-west and the Golan Heights in the north-east.

How the Arab military were able to trick Israel into believing that massive troop movements in Egypt and Syria did not forebode an imminent offensive, remains subject to academic debate. Perhaps Israel was overwhelmed by what an American military analyst later called ‘an impertinent sense of invulnerability’.

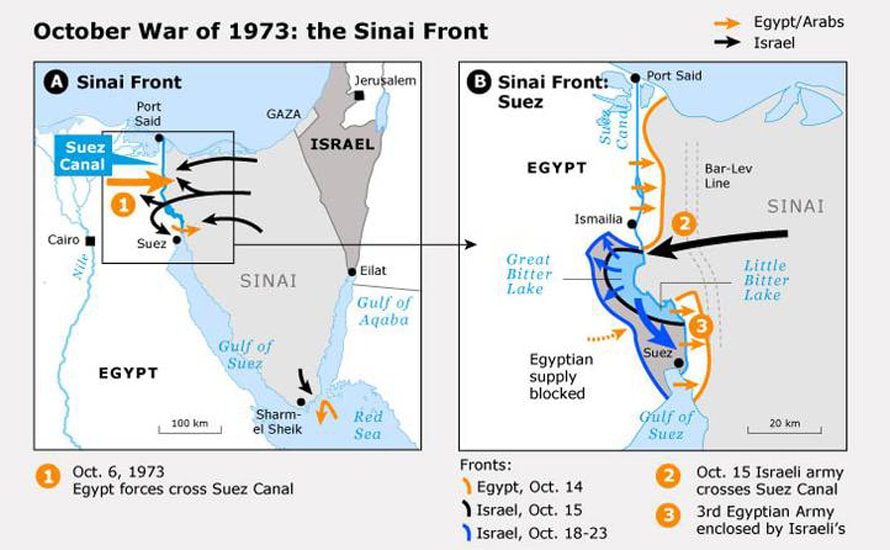

The October War began on the Jewish holiday of Yom Kippur, in the Islamic month of Ramadan (hence the names Yom Kippur War or Ramadan War). The surprise was complete. Tens of thousands of Egyptian troops crossed the Suez Canal with amphibious vehicles and bridging equipment. Opposing them were only hundreds of Israeli troops positioned in bunkers, that were quickly overrun.

Israel had always put trust in its airpower to quickly destroy any Arab offensive that would threaten the country. In this respect the 1967 Occupied Palestinian Territories, the Golan and the Sinai offered strategic depth. But the Egyptians had anticipated that the Israeli Air Force had a quantitative and qualitative edge over the Arabs. The Egyptian troops were protected by the latest Soviet air defence equipment, including radar controlled guns and shoulder fired surface-to-air missiles. Before the evening this multilayered umbrella had succeeded in destroying 30 counter-attacking Israeli aircraft. At this rate, the Israeli Air Force would not last for two weeks.

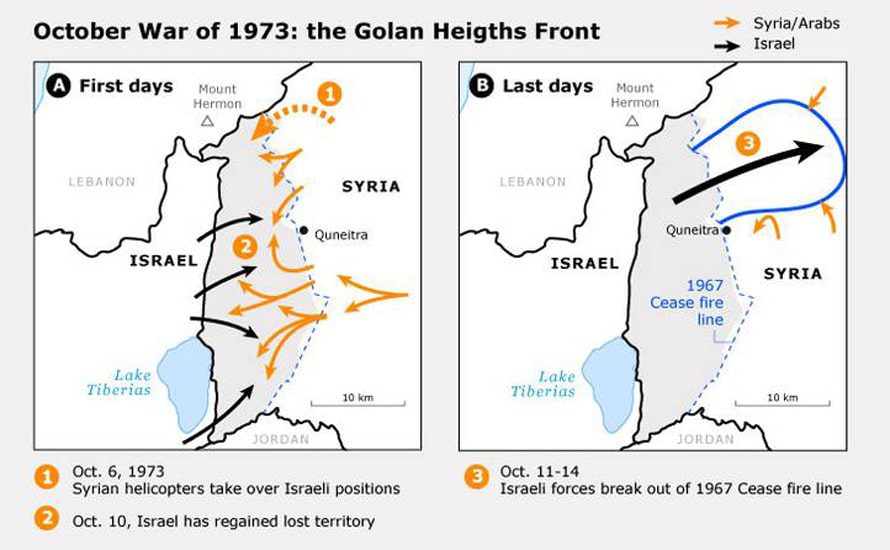

On the Golan front the surprise was as great as in the Sinai. The Israeli troops held the high grounds but were outnumbered by the Syrians ten to one, in men, tanks and artillery pieces. With a daring helicopter assault on an intelligence outpost on the summit of Mount Hermon, Syrian commandos beat the Israeli forces at their own game. The Syrians got hold of some American high-tech intelligence equipment, but their aim was more ambitious: to throw the two armoured brigades with 180 tanks from the Golan Heights, dig in with their circa 1,300 tanks and create a ‘fact on the ground’. This was Israel’s darkest hour in the war. From a general’s viewpoint the Syrian tank army looked on the threshold of entering Israel proper.

The Syrian tanks did not succeed. The two Israeli armoured brigades profited from prepared positions, higher ground and marksmanship and narrowly defeated the Syrian onslaught. After a few days the Syrian and Egyptian fronts were stabilized. The war had brought Israel on the brink of defeat, but as a result of massive arms shipments by the United States and other Western states, Israel was able to regain the initiative on the battlefield and ultimately defeated both the Egyptian and the Syrian Armed Forces. By the end of the war, 2,200 Israelis soldiers had been killed, four times as many as in the June War. Another 5,600 were wounded. 8,500 Arabs were killed – many of them Syrian – but far fewer than the 16,000 lost during the June War.

For more in depth information, see The October War in Arab-Palestinian-Israeli Negotiations and Wars.