Introduction

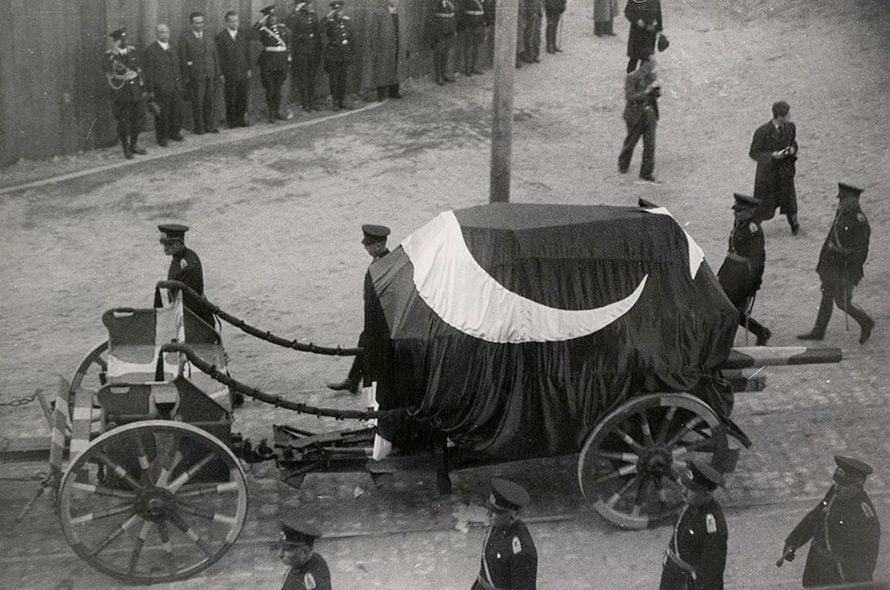

The transition to political pluralism that was inevitable following the ‘Germanophile’ policy of the regime of İsmet İnönü, who replaced Mustafa Kemal Atatürk after his death in 1938, led to political change in 1950. Between 1950 and 1960, the government of Adnan Menderes (1899-1961), of the Democratic Party – which became very authoritarian especially after the elections of 1957 – was opposed by part of the Army and by young students.

Menderes was overthrown by the 1960 coup d’état and executed, with two other ministers. The military coups d’état of 1971 and 1980, which targeted mainly the radical left, showed the extent of political instability in the country, which was an ally of the West during the Cold War.

1983 - 1997

The last military intervention occurred after a period of violence characterized by confrontations between radical left- and right-wing parties and numerous pogroms, especially against the Alevis, which claimed 6,000 victims; an Islamicist, ultra-nationalist, and Kemalist doctrine was adopted, with the aim of militarizing the political environment and society.

Despite its official end, marked by the victory in 1983 of the Motherland Party of Turgut Özal (1927-1993) – a conservative politician who opted for liberal solutions to solve the Kurdish issue shortly before his disappearance, which many believed was a homicide – the country could not escape the authoritarianism that was imposed by the Constitution of 1982, which had been prepared under the aegis of the military.

The new period was also marked by the emergence of the Kurdish guerrillas of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (Partiya Karkerên Kurdistan, PKK) that has, from 1984 to the present, claimed more than 40,000 victims, and by the rise of political Islamism, represented by the Welfare Party of Necmettin Erbakan (1926-2011).

Various weak coalition governments followed throughout the 1990s, which left the Army free to manage the Kurdish issue and political Islam. Death squads spread terror in Kurdistan and engaged in a murderous war with the state, and the military succeeded, on 30 June 1997, in pressuring Erbakan, who had been appointed Prime Minister a year earlier, to step down.

Since 2002

But despite the military’s fierce opposition, it was unable to prevent the victory in the 2002 elections of the Justice and Development Party (AKP) – a party that had been created from a faction of the Islamist Party under Erbakan – led by Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.

By advocating democratization, social ultra-conservatism, economic neoliberalism, the greatness of Turkish-Ottoman history, opposition to Israel, and pragmatism in his relationships with Washington, Erdoğan defied all odds and became ‘the Single Man’ in the Turkish political space. His party won 50 percent of the vote in the 2011 elections.

Although the Army continues to play a direct role in the Kurdish issue, it has otherwise been largely marginalized as a result of the discovery of its abortive coups d’état. Between 2009 and 2012, more than 100 senior officers were arrested and charged. Erdoğan’s political success and durability are due partly to the support of the provincial bourgeoisie and puritan middle-classes, which see Erdoğan as both a protector of a conservative social order and a leader restoring the nation’s pride.

Another factor is the support of Erdoğan’s AKP by the so called ‘Fethullahci community’, built by the Islamic scholar and preacher Fethullah Gülen (exiled to the United States), which is accused of infiltrating many organs of the state. In fact, this community has replaced the Kadiri and Nakşibendi religious brotherhoods as the main pillar of the conservative and religious movement in Turkey. Erdoğan defines poverty as a non-political question that should be dealt with through charity and so enjoys the support of many low-income Turks.

The government of Erdoğan, hailed by some observers as the model for ‘Islamic democracy’, began negotiations concerning Turkey’s accession to the European Union in December 2004. That accession was supposed to be completed by 2014 but has come to a standstill for many reasons, including the reluctance of former French President Nicolas Sarkozy and German Chancellor Angela Merkel; the refusal of Ankara to recognize Cyprus (of which 40 percent has been occupied by the Turkish Army since 1974) as a united and independent state; and the Justice and Development Party’s shift towards authoritarianism and conservatism since the 2010s, even though it had demonstrated democratic openness during the first years of its rule.