Introduction

Turkey’s population increased by 459,365 people in 2020 AD compared to the previous year 2019 AD, reaching 83,614,362 people.

According to the Turkish Statistics Institute, the percentage of males in the total population was about 50.1% (41 million, 985 thousand, and 915 people). In comparison, the percentage of females was 49.9% (41 million, 698 thousand, and 377 people) with a gender ratio of 102.4 males per 100 females.

The annual population growth rate decreased from 13.9 per thousand in 2019 to 5.5 per thousand in 2020, and the percentage of the population in cities and villages decreased from 7.2% to 7%. The percentage of residents in governorate centers and neighborhoods increased from 92.8% in 2019 to 93—% In 2020.

Turks make up between 70-75% of the country’s total population, while the Kurds make up about 19%, and other minorities between 7-12%, according to estimates published by the CIA World Factbook.

The United Nations estimates the number of international refugees hosted by Turkey on its soil at 5.877 million refugees, accounting for 7% of the total population.

Turkey hosts about 3.6 million registered Syrian refugees, according to 2019 estimates, in addition to thousands of unregistered people. And those who fled their country as a result of the ongoing war on their lands since 2011.

The Turkish language is the official language, with the Kurdish language and other languages for minorities.

The government has not collected data on the ethnic origins of citizens since the 1960 Census. At that time, Arabs (whose mother tongue is defined as Arabic) only constituted 1.25% of the total population, with the largest percentage of them spreading to three southern provinces: Hatay (34%), Mardin (21%), and Sanliurfa (13%).

Other data indicate that the national figure has not changed much over the decades. For example, in a national survey conducted by the Kunda Foundation in 2007, it was found that 1.38% of the respondents declared that their mother tongue is Arabic. However, the overwhelming influx of Sunni Arab refugees from neighboring countries has brought about drastic changes in the southern provinces with the largest Arab population.

The overwhelming majority of the population are Muslims. Their percentage is estimated at 99.8%; most of them belong to the Sunni community, while the remaining religious minority is 0.2%, most of them are Christians and Jews.

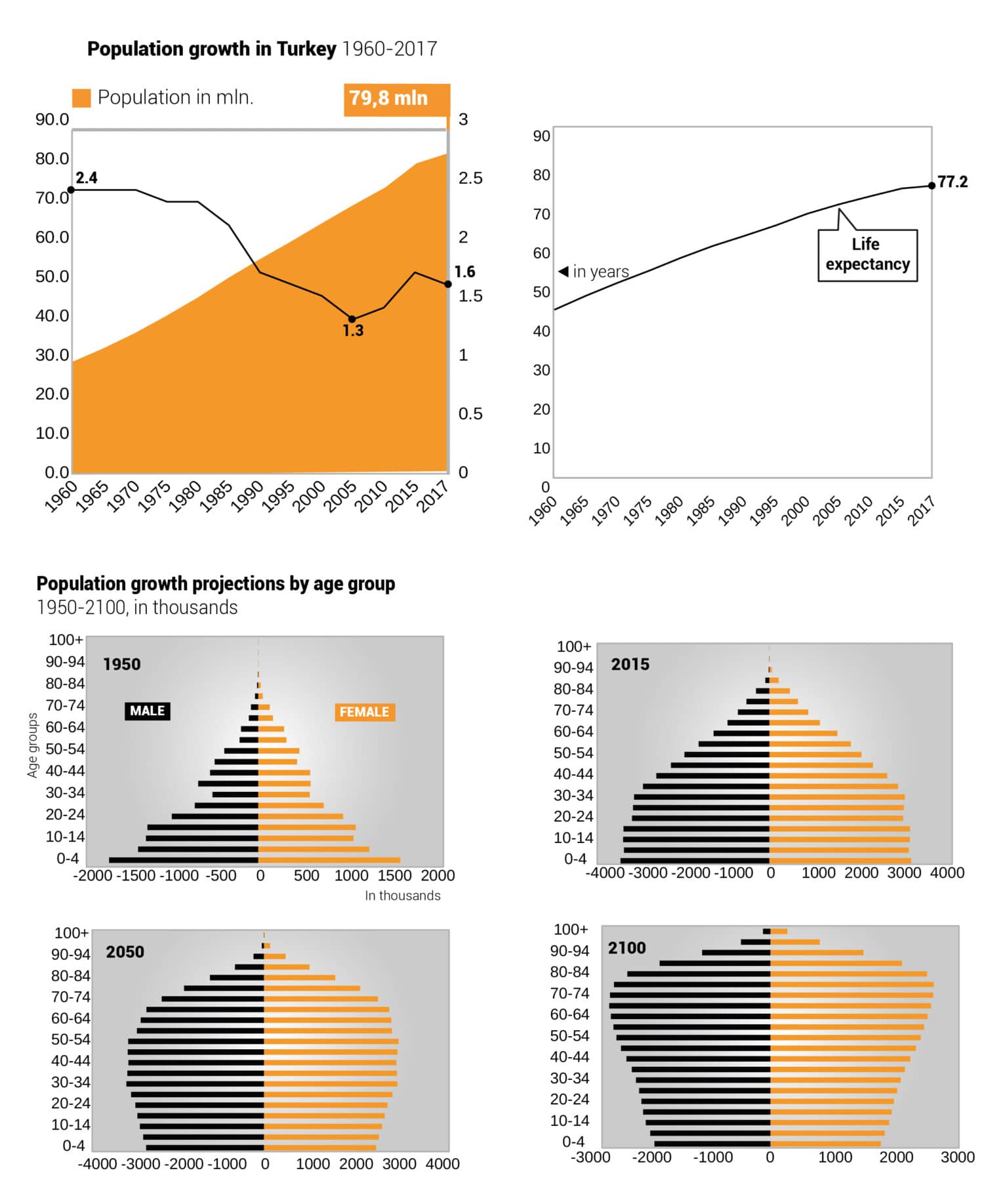

Age Groups

The Turkish government has not succeeded until today in its endeavor to raise the rates of population growth and address aging in the country. Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has repeatedly called for Turkish families to have at least three children.

According to the Turkish Statistical Institute, the number of people aged 65 years and over in Turkey who are considered elderly has increased by 22.5% in the past five years (2015-2020 AD). They have reached 7 million and 953 thousand and 555 people in 2020 AD, and it is expected To rise to more than that in the current decade. Experts link these expectations to declining fertility rates and the availability of new treatments contributing to an increase in longevity.

According to the data of the World Bank for the year 2019 AD, the percentage of the population under the age of 15 was estimated at 24.3% of the total population, while the percentage of the population in the age group between 15 years and 65 years was estimated at 67%. For those 65 years and over, They account for 8.73% of the country’s total population.

Turkish women’s fertility rate is among the lowest rates, and it reached 2.1 births per woman in 2020 AD, and the average life expectancy in the same year was 77.25 years (74.3 for males, 80.2 years for females).

Areas of Habitation

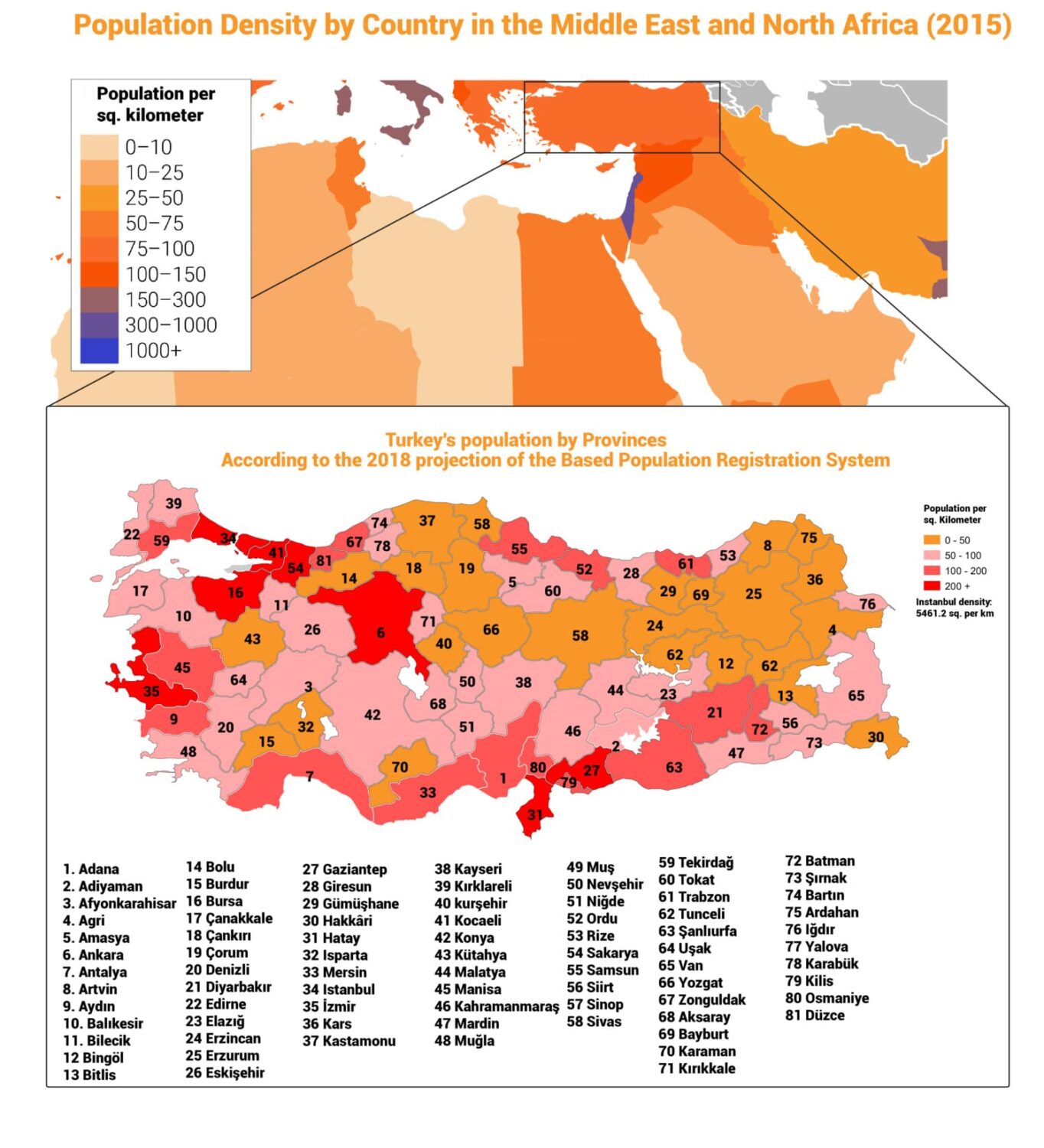

Source: https://www.tuik.gov.tr/Home/Index. @FanackThe population density was about 109.6 people / km2 in 2020 AD, and the rate of residents in state and district centers (urban residents) increased from 92.8 percent in 2019 to 93 percent during 2020 AD. In contrast, the rate of residents in towns and villages decreased from 7.2 percent to 7 percent.

Istanbul ranks first in the country in terms of population density, about 18.6% of the total population of the country, according to the Turkish Statistical Institute, followed by the capital, Ankara, with 5.95%, in second place, Izmir by about 5.3%, while Bursa ranked fourth with 3.6% of the total population, and Antalya is fifth at 2.9%.

Ethnic and Religious Groups

The demographic history of Turkey is complicated and critically important. Researchers have shown the extent to which new demographic engineering, aimed at unifying the country religiously and then linguistically, was developed between the reign of Abdülhamid II (1876-1909) and the end of the Kemalist Republic in 1945.

About 20 percent of the Turkish population was non-Muslim in 1914, compared to less than 1 percent today. About 40 to 50 percent of the current Turkish population is from the Balkans or the Caucasus.

Because there were no questions related to the mother tongue or self-identification of people in censuses taken after 1965, observers were obliged to rely on rough estimates of Turkey’s ethnolinguistic composition. Turks constituted the overwhelming majority, about 80 percent of the total population, followed by the Kurds, who speak the Zazaki and Kurmanji languages and are estimated at 18 percent of the total population.

(In 1927, the total Turkish population increased to 13,648,270, of whom 1,184,446 stated that Kurdish as their mother tongue. In 1965, this figure was 2,219,502, out of a total population of 31,391,421. However, the forbidding of expression of Kurdish identity prevented many Kurdish speakers from admitting their mother tongue in these two censuses). Defined either as Kurdish dialects or languages by specialists, the Kurmanji and Zazaki (or Zaza or Dimli) languages also belong to the Indo-European language family.

The Laz, who speak a language belonging to the North Caucasian language family and who number fewer than 200,000, live mainly on the coasts of the Black Sea. The population of Arabic speakers in the country’s southern areas (e.g., Adana, Mersin, Hatay, Mardin) has fallen considerably. Many groups – such as the Abkhaz people, the Caucasian Circassians, the Albanians, and the Bosniaks – settled in Istanbul or Anatolia due to the wars and population movements of the 19th and 20th centuries. They are regarded as Turks but seem to have maintained many special features and language skills, including favouring endogamous marriages.

Religious Composition

As there are no reliable data on the religious composition of Turkey, we must rely on rough estimates: Sunni Muslims constitute the overwhelming majority (about 80-85 percent of the population), while the Alevi community, which emerged as a result of religious differences in the 16th century, is the most important religious minority.

However, Alevism, whose dogma is structured around a trinity consisting of Allah, Muhammad, and Ali, as well as the doctrine of wahdat al-wujud (Turkish vahdeti vücud or varlık birliği, ‘unity of existence’), is not accepted by the state which only recognizes Sunni Islam based on the Hanafi school of law. Other minority communities include the Shiites (about 100,000 persons) and the Yazidi Kurds, who are part of the Manichaean tradition.

Since the early Ottoman Empire period, Islam in Turkey has been structured around two groups: the ulama and the religious brotherhoods. The ulama, who had the status of civil servants and belonged to the ‘military class’ (i.e., privileged ruling class that did not pay taxes), were directly integrated into the state, acting as religious men and judges for internal regulations and sanctions.

On the other hand, the Sufi religious brotherhoods did not form part of the state. They enjoyed a de facto autonomy, allowing them to have their tekkes and zaviyes (‘convents’) and social networks. While generally trying to avoid confrontation with the state’s authority, the religious brotherhoods on occasion assumed the role of political or even armed opposition.

The Nakşibendi (Naqshbandi), Kadiri (Qadirya), Mevlevi (Mawlawiya), Bektaşi (Bektashi), Cerrahi (Jerrahi), and Halveti (Khalwati) communities were among the most important religious brotherhoods under the Ottoman Empire.

Most of these religious brotherhoods remain active in the Republic of Turkey. One brotherhood, in particular, has played an important political role from the 19th century: the Nakşibendi (Naqshbandi) brotherhood, founded by Baha-ud-din Naqshband Bukhari (1318-1389), which was radically renewed in the 19th century by a Kurdish Sheikh, Mawlana Khalid-i Baghdadi (Mevlana Halid, 1779-1827).

This brotherhood obtained favours from the Ottoman Palace under Abdülhamid II’s rule (ruled 1876-1909) but formed the direct opposition under the Kemalist regime. Some Kurdish Naqshbandi sheikhs in the 1925 Kurdish revolt resulted in the ban on all religious brotherhoods. Still, the Nakşibendis (and other religious brotherhoods) continue to play an underground social and political role.

The İskenderpaşa Cemaati (Iskender Pasa) (Istanbul) community of Mehmed Zahid Kotku (1897-1980, led after his death by his son-in-law professor Esad Coşan, 1938-2001), constituted one of the most important social bases for right-wing parties, among them, Necmettin Erbakan’s Islamist party.

Other religious communities – very different from religious brotherhoods – such as the Isikçis and Süleymancis also emerged in the 20th century. One of these communities, formed by a former Kurdish member of the Nakşibendi order, Said Nursi (1878-1960), is organized among the Turkish urban middle classes. This movement, called Nurculuk, transformed itself into one of the main intellectual and political forces behind the conservative parties in the 1960s and 1970s.

In the 1980s and 1990s, one of its disciples, Fethullah Gülen (born in 1941), was able to build up a large network of schools where mainly middle-class male children are educated and a media network, publishing one of Turkey’s most important newspapers, Zaman. In the 1990s, Gülen was declared ‘most dangerous terrorist’ by the Turkish army, leading to his on-going exile in the United States.

His movement, however, is supposed to have largely infiltrated the state’s apparatus on different levels, including among the high-ranking security milieu. There is no doubt that the Gülen movement is the main intellectual/administrative pillar of Turkey’s Erdoğan government. However, signs are indicating that the relationship between Gülen and Erdoğan is not cordial.

Finally, the Christian community (several tens of thousands of Assyrians, nearly 60,000 Armenians, and fewer than 3,000 Greeks) is gradually shrinking, and there are fewer than 30,000 Jews.

Minorities

Although Turkey is officially a secular state, the borders that separate the ‘state’ from ‘minorities’ are primarily religious. In a tradition that dated back to the last few Ottoman decades and was legally formalized by the Treaty of Lausanne (1923, the Republic of Turkey’s founding act), Muslims are generally considered Turks regardless of their origin or language. Therefore, the Kurds (around 18 percent of the total population), whose existence is now recognized by the Turkish government, are not considered a minority and are not entitled to any special rights in education or administration.

Furthermore, all Muslims are implicitly considered Sunnis, as Sunni Islam is the nation’s default religion. Accordingly, the Alevis and the Yazidis, who have dualistic beliefs and in some cases publicly reject Islam, have never been recognized as religious minorities. The Presidency of Religious Affairs, which reports to the Prime Minister and employs around 100,000 ‘men of God’ and controls all Muslim religious institutions, is funded by all taxpayers (including Christians and Jews) but serves only Sunnis. All claims for legal recognition by linguistic or religious minorities are still rejected by the authorities and a large part of the political class.

On the other hand, since the Treaty of Lausanne, the Armenians (nearly 60,000), the Greeks (fewer than 3,000), and the Jews (fewer than 30,000) have been legally recognized as minorities and thus do not constitute a part of the Turkish nation, even though they enjoy the same civil rights. Ankara undertook, under several clauses in the treaty, to protect these minorities, but Ankara has not always fulfilled this obligation, as illustrated by the exclusion of Christians and Jews from public service in the 1920s; the anti-Semitic campaigns of 1934; the wealth tax imposed almost exclusively on Christians and Jews in 1942; and the anti-Greek pogroms of 1955 and the confiscation of the funds of the religious foundations of the Greek patriarchate.

The state’s official position and much of the political class and the media have always been hostile towards these minorities, which are considered internal enemies. Over the past fifteen years, a new school of historians, who might be described as dissidents, has been addressing the repressions they have subject to throughout the 20th century.

Discrimination

Jewish and Christian minorities in the country, considered second-class citizens, are victims of much discrimination, media lynching, and violence, as was the case with Hrant Dink, a world-famous Armenian intellectual assassinated January 2007. Gypsies, known officially in Turkish as ‘Romans,’ had integrated themselves well into many cities’ social structures but were subject to discrimination for long periods. Their number is estimated at 750,000, and they live particularly in Thrace, Greater Istanbul, and the coastal towns of the Mediterranean.

The Alevis have often been subject to discriminatory practices and speech, even though the pogroms to which they were subjected in the 1970s (especially in Çorum, Sivas, and Kahramanmaraş are now a thing of the past. There are also silent, relatively compact communities, such as the Armenian-speaking Muslims known as the Hamshinis (Hemshin people) who live in complete isolation in Artvin Province and number an estimated 40,000 people.

Syrian Refugees

Syrians constitute nearly a third of the total refugee population in the world, and Turkey hosts more than 64% of them, according to United Nations statistics, as the number of Syrian refugees reached 5,556,417, according to the statistics of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) on January 30, 2020. The number is concentrated. The largest of them is in Turkey, with a total of 3,576,344 refugees. Simultaneously, the number in neighboring Lebanon reached about 915 thousand refugees, and about 655 thousand in Jordan, while the rest were distributed between Iraq, Egypt, and other countries around the world.

The influx of Syrian refugees between 2011 and 2017 is the most important demographic shift in Turkey since the “population exchange” with Greece between 1923 and 1924. The Turkish government opened its doors to people to escape the Assad regime’s brutality in April 2011, resulting in one million people fleeing across the border by September 2014. A year later, the number doubled to two million and exceeded three million in 2017.

According to 2019 estimates, Istanbul has the largest concentration of Syrians among Turkish cities, as their number there reaches 547 thousand and 716 Syrians. They account for about 3.64 percent of the city’s population.

After Istanbul comes, Gaziantep, Hatay, anlıurfa and Adana. These cities also contain temporary residence centers where 445,154 people live in Gaziantep, in Hatay 431 thousand and 98, in anlıurfa 430 thousand and 237, and Adana 240,000 752, according to official statistics.

Bayburt, in north-eastern Turkey, is the least populous city for Syrians, as only 25 Syrians live in it.

Kilis has the densest Syrian presence in the population; Syrians’ percentage reaches 84.41%, followed by Hatay with 26.71%, then Gaziantep with 21.90%.

The cities that are least densely populated with Syrians relative to their population are Artuin, located in north-eastern Turkey near the Georgian border, where they account for 0.02 percent of the city’s population.

The percentage of males among Syrians in Turkey is 54.15 percent, amounting to 1 million 970 thousand and 516 people, compared to one million 668 thousand and 768 women, or 45.85 percent.

A statistic of the Turkish General Immigration Department on August 14, 2019 AD indicated that 21,988 illegal Syrian immigrants were arrested in the country during this year.

It is noteworthy that in 2014 the number of illegal Syrian immigrants arrested in Turkey reached 24,984 immigrants, and in 2015 it increased to 73,000 422 people. It decreased in 2016 to 69,755 people and 50,217 people in 2017 and reached. In 2018, there were 34 thousand 53 immigrants.

Refugees and Arabic-speaking citizens make up 56% of Hatay’s population, making it the first Arab-majority province in Turkey. While Alevis dominated Hatay’s Arab community before the war, the influx of refugees has made the Sunni Arab and Alevi communities equal in size. Likewise, the percentage of the Arab population in Kilis was less than 1%, but it is now expected to become the second-largest Arab province in Turkey. In this regard, some reports have indicated that the Arab population has made significant jumps in the population in Mardin (from 21% to 31.2%) and Sanliurfa (from 13% to 32.3%).

It is reported that a cash assistance program funded by the European Union is designed to help the Turkish state contain refugees worth 3 billion euros (2.6 billion pounds sterling); It was agreed upon in March 2016, this assistance to share the burden of refugees with the host country, assistance in taking care of refugees within its borders, which would help Turkey to curb irregular migration to Europe. The High Commissioner for Foreign Affairs of the European Union, Federica Mogherini, announced in April 2018 that the Union intended to allocate an additional 3 billion euros to Turkey to help Syrian refugees in 2019 and 2020.

Iraqi Refugees

It was disturbing to see Yazidi refugees from Iraq being sent back in August 2014 from Turkey into Iraq by the Turkish border police. The refugees were clearly visible from a road close to the border. They were wearing colourful clothes and were thus easily visible against the background of green trees in the valley, running the river that they had just forded to cross into Turkey. In Turkey, villagers were ready to offer the refugees blankets, bread, and water. They booed the border police from a distance when they saw how the group was approached by men in uniform and guided to wade back through the river once again.

The scene unfolded close to Habur, the official border crossing between Iraq and Turkey. Habur is on the road that connects Zakho, in Iraqi Kurdistan, to Silopi in Turkey. The refugees decided to get into Turkey illegally because of the Turkish government’s policy on Habur: only refugees with a passport could cross the border there. Since most people had no passport, there was no other option but to cross rivers, fields, and mountains.

Most refugees chose the mountains and crossed the border in the Uludere district, in Sirnak Province, using the same illegal border crossing where the Uludere massacre took place in late December 2011, in which bombs killed 34 Kurdish smugglers from Turkish fighter jets.

One of the major problems faced by Iraqi refugees in Turkey originates from this policy of allowing only those who have passports: families were torn apart. People were so afraid of what the Islamic State had in store for them that breaking up the family seemed preferable to staying together in Iraq. Some even felt forced to leave their young children behind with relatives because they hadn’t yet been able to obtain passports for them.

It was not only the advance of the Islamic State that frightened the Yazidis—Kurds with an ancient religion who are considered ‘devil worshippers’ by the Islamic State—but also the fact that their town, Sinjar, and surrounding villages were left unprotected by the armed forces of Iraqi Kurdistan, the peshmerga.

Kurdistan

Yazidi refugees who could not get into Turkey were mostly stranded in the Iraqi Kurdistan towns of Zakho and Duhok. The local population was ready to help with the most basic needs, such as blankets, food, and water, but shelter was a serious problem. The Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) deals with a huge influx of refugees from other parts of Iraq, some 1.4 million people in all. The government’s budget is not sufficient to care for all of these people properly. This lack of funds is also due to a conflict with the central Iraqi government in Baghdad, which is not sending the KRG in Erbil the 17% of Iraqi oil revenues to which it is entitled.

Many refugees in Zakho and Duhok were thus forced to stay on the streets, under bridges, and in empty buildings, not properly protected against the scorching summer heat. With winter coming, the situation will deteriorate even further. The Turkish Disaster and Emergency Management Directorate (AFAD) tries to help and has built two camps for the Yazidis in Iraqi Kurdistan.

It is estimated that there are 250,000 Yazidi refugees in Zakho and Duhok. Altogether, more than a million internally displaced persons and refugees are have taken refuge in Iraqi Kurdistan. The internally displaced are mostly from Nineveh province, including Yazidis and inhabitants of Mosul, the city taken over by the Islamic State in June 2014, and smaller refugee groups, such as the Shabak ethnoreligious minority and groups of Christians. The refugees are from Syria, including Syrian Kurdistan.

Unequal Treatment

An estimated 35,000 Iraqi citizens have fled to Turkey, 99 percent of whom are Yazidis. There is a substantial difference between these refugees and those who came to Turkey from Syria: the Syrian refugees, numbering around 2 million (figure based on local estimates), are subject to the Temporary Protection Directive, while those from Iraq are not.

This directive was passed by the Turkish parliament in October 2014 and has yet to be implemented. It gives the Syrian refugees, among other things, a firm legal status, the right to stay in Turkey, and access to health care and provides for an identity card that facilitates entrance to state schools and the labour market. The directive was preceded by several ministerial circulars dealing with Syrian refugees.

The Iraqi refugees began coming to Turkey only in the summer of 2014, and it remains to be seen if and how fast a similar arrangement will be made for them. The Iraqi refugees are not, however, totally without rights. They can, for example, register and receive a document that gives them access to free healthcare. On the other hand, according to the law, the refugees can get in trouble because they crossed the border illegally and are staying in Turkey without permission; this causes the refugees to feel insecure and fear being sent back to Iraq.

Some 2,000 to 2,500 Yezidi refugees are in a state-run refugee camp near Midyat, in the south-eastern Turkish province of Mardin. This camp was set up about three years ago to host Arab refugees from Syria. Because the camp can provide shelter for 7,000 people and about 5,000 Syrians were sheltered there, the remaining space was given to Yazidis.

Municipalities support the remaining 35,000 Yazidis, often administered by the Kurdish DBP (Democratic Regions Party) and the local population. The problem is that the municipalities don’t have adequate funds to provide sufficient aid to all the refugees. This becomes more problematic as winter sets in, and the tents the people are housed in don’t provide adequate shelter from the increasingly harsh conditions.

Many of the Yazidi refugees have no intention of returning to their homes in Iraq, even if the situation stabilizes in the future. Many tell stories of their Arab neighbors conspiring with the Islamic State and looting Yazidi houses as soon as the Yazidis left. They feel they will never be safe again in their ancestral lands, and many want to resettle in Europe.

Some have already attempted the journey from Turkey to Europe, and the first news stories about Yazidis drowning in the Mediterranean have already appeared.