State Borders

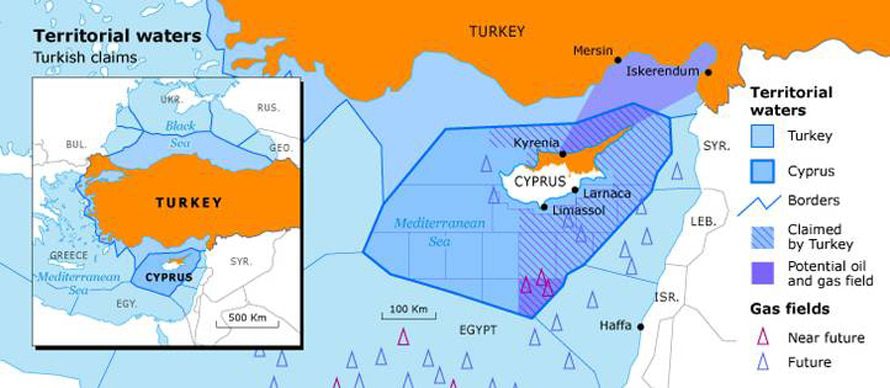

Located at the crossroads of Asia and Europe, Turkey shares borders with Syria (877 kilometers) and Iraq (331 kilometers) to the south; Iran (454 kilometers), Armenia (316 kilometers), and Georgia (276 kilometers) to the east or north-east; and Bulgaria (269 kilometers) and Greece (212 kilometers) to the north-west. The country also has about 5,000 kilometers of maritime borders with Romania, Russia, Ukraine, and Cyprus.

Separating as they do the Arabic, Persian, Russian, and Turkish states or cultural areas, large Turkish borders have been subject to conflicts throughout history. The 16th century was marked by chronic conflicts between the Ottoman Empire and Persia, which made no major changes to the borders defined between the two states by the Treaty of Chaldiran in 1514. The conflict between Russia and the Ottomans, which was intense in the 19th century, resulted in many changes in the borders, especially following the end of the 1877-1878 war before those borders were permanently defined by Moscow’s Treaty (1921). Turkey’s borders with Iraq and Syria were defined after the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire and the British and French occupation of the former provinces of the Sublime Porte following World War I in October 1918. The western borders were defined by the retreats and advances of the Ottoman Army during the Balkan Wars of 1912 and 1913 and were confirmed at the Conference of Lausanne in 1923.

The Turkish borders were highly militarized throughout the 20th century and remain so today: despite the short-lived Balkan Pact of 1934 between Turkey, Greece, Romania, and Yugoslavia, relations between Ankara and Athens were often tense; the borders with Bulgaria and in the Caucasus were heavily militarized during the Cold War, as were the borders with Iran, Iraq, and Syria, which divide Kurdistan into four state entities. The Armenian-Turkish border has remained closed since the Karabakh conflict between Yerevan and Baku (1988-1994), which intensified after the USSR’s dissolution in December 1991.

Geography and Climate

In 1920, the Kemalist regime (1923-1945) replaced Istanbul with Ankara as Turkey’s capital and divided the nation into seven regions: Marmara, Aegean, Black Sea, Mediterranean, Central Anatolia, Eastern Anatolia, and South-Eastern Anatolia.

Eastern Thrace – which includes the provinces of Edirne, Kırklareli, and Tekirdağ, and the European part of Istanbul – represents only 3 percent of the country’s total area (780,000 square kilometers). The population of Thrace outside Istanbul is 1,521,328, or 2.1 percent of the total population.

The ‘Great Istanbul’ projects put forward by the government of Prime Minister Erdoğan include, in particular, a third bridge connecting Europe and Asia to attract an average of two million people to this area shortly.

Turkey has few lakes – the largest is Lake Van, with an area of 3,755 square kilometers – but it has many rivers, including the Tigris (1,900 kilometers) and the Euphrates (2,780 kilometers), which have their sources in the same area; the Kızılırmak (Red) River (1,150 kilometers); the Yeşilırmak (Green) River (520 kilometers); and the Büyük and Küçük Menderes (Great and Little Maeander) rivers (548 kilometers and 175 kilometers respectively).

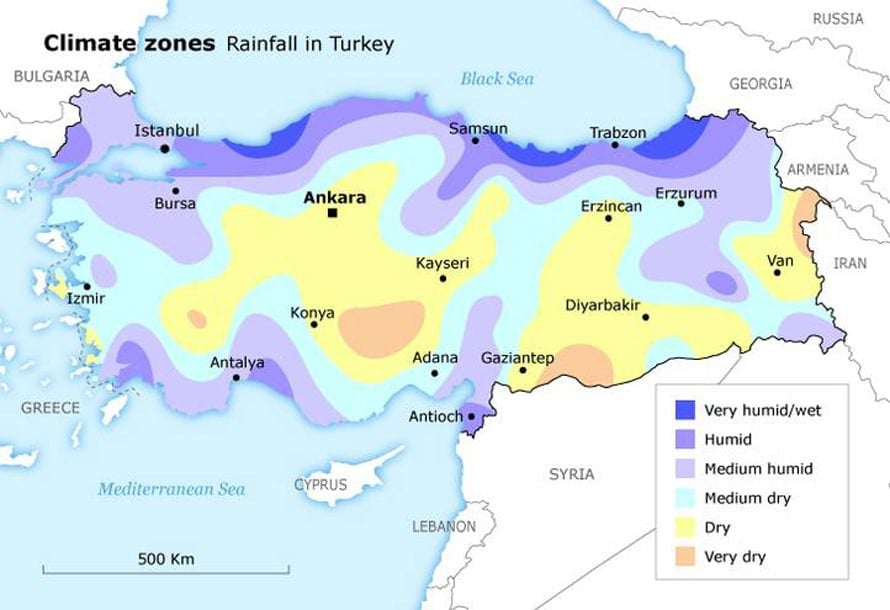

Turkey’s landscape is diverse, with strong contrasts, from Thrace to the Caucasus, including coastal regions and Anatolian steppes. This diversity affects the climate, which is the Mediterranean on the coasts of the Aegean and the Mediterranean Sea, temperate and rainy on the coasts of the Black Sea, continental in the central parts, semi-arid in the south-east, and continental, with Siberian winds, along the Caucasus Mountains borders with Iran and Armenia.

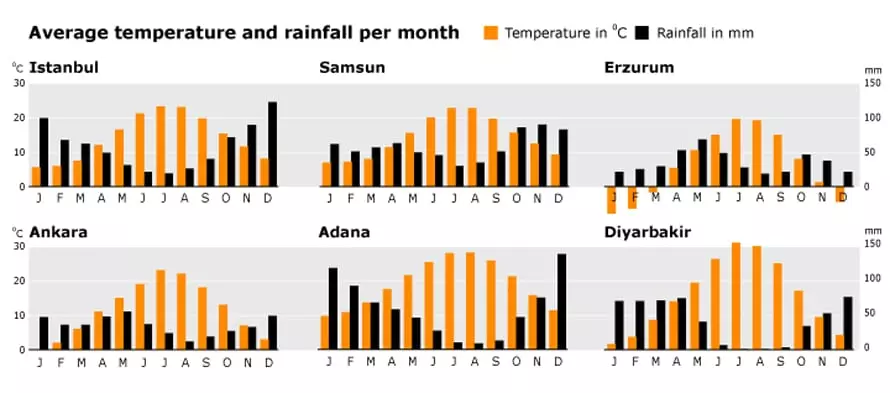

The maximum temperatures in Istanbul range from 18 to 28 °C during the summer and decrease to 5 °C during the winter. Ankara’s temperature varies seasonally from 0 to 30 °C. The average annual temperature in Izmir and much of the Mediterranean area is always high (16 °C). The temperatures range seasonally from 3 to 40 °C in Şanlıurfa; minus 2 to about 40 °C in Diyarbakır; minus 12 (with minimum temperatures as low as minus 35) to 27 °C in Erzurum; and 3 to 26 °C in Zonguldak, on the Black Sea coast. Rainfall varies considerably by region and season, ranging from 10 to 50 millimeters in Ankara; from 20 to 70 millimeters in Diyarbakır and Şanlıurfa; from 21 to 70 millimeters in Erzurum; from 21 to 105 millimeters in Istanbul; and from 50 to 140 millimeters in Zonguldak. Seasonal variations explain the drought observed in much of Turkey, especially between June and September.

Earthquakes

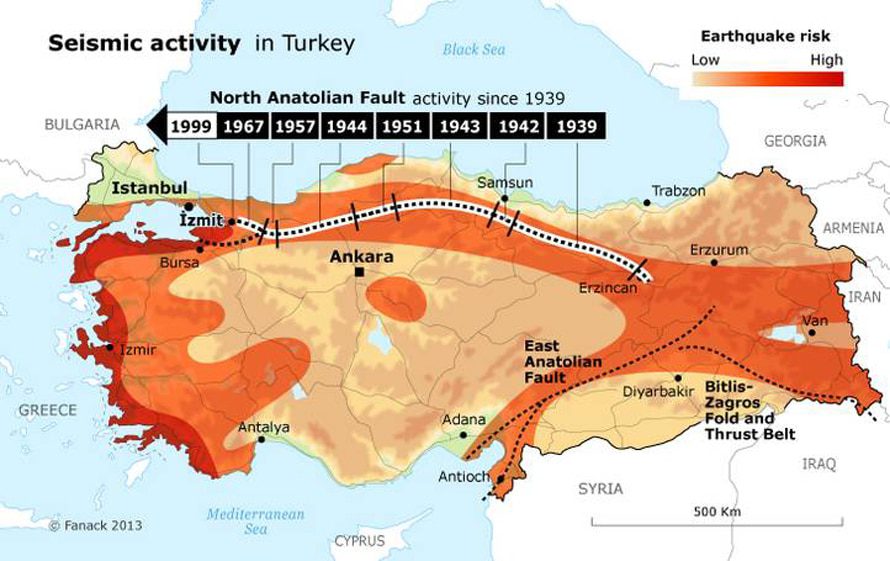

Turkey is situated in a part of the world subject to high levels of seismic activity. Fifteen to twenty light earthquakes are monitored daily. Heavy earthquakes occur periodically.

A fault line runs straight across Anatolia from the southwest to the northeast. The fault line stretches along the plate boundary in a collision zone between the Arabian plate in the east and the Anatolian plate in the west. The northward migration of the Arabian plate causes horizontal fault slips, storing strain energy which, when released, results in earthquakes.

Most of the earthquakes occur in the so-called North Anatolian Fault zone (parallel to the Black Sea coast) and the East Anatolian Fault zone (in Turkish Kurdistan). With a 7.6 magnitude on the Richter Scale, Turkey’s most recent devastating earthquake took place on 17 August 1999 in the Kocaeli province in West Turkey. The epicenter was located to the southwest of İzmit, 80 kilometers from Istanbul, in a densely populated and highly industrialized area. The earthquake took place in the middle of the night when most people were asleep and in a densely populated area, which explains the high death toll – conservative estimates put the figure at around 17,000 – and the number of casualties – 45,000 injured. About 70 percent of the buildings, including many industrial facilities, sustained heavy damage and collapsed. On the whole, the infrastructure suffered severely. At the time, the total material damage was estimated at USD 5 billion.

North Anatolian Fault

Scientists have signaled an eastward migration of the earthquakes along the 1,300 kilometer-long North Anatolian Fault zone, prompting the question of whether Istanbul, with its population of thirteen million, will be hit by an earthquake.

Biodiversity and Natural Environment

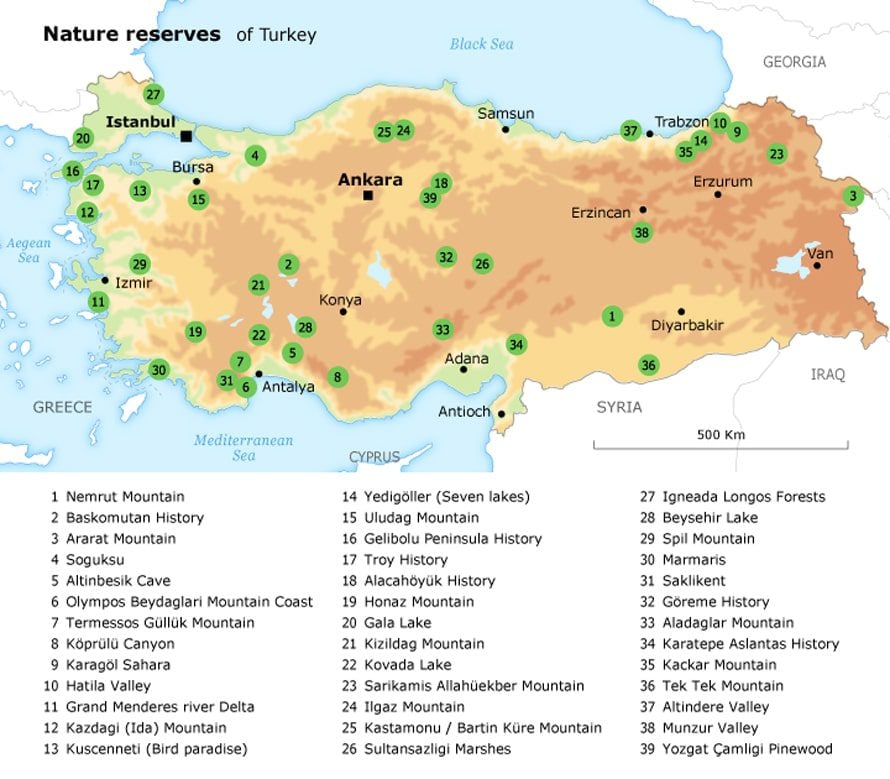

Because it has many climatic zones, Turkey has nearly 3,000 endemic plants, plants that are found exclusively in one of its regions. The Worldwide Fund for Nature (WWF) has welcomed the awareness – even if it has been slow in coming – of the authorities in Ankara, who have, in the last few years, established SPAs (Specially Protected Areas) and participated fully in the activities of the Turkish government’s Environmental Protection Agency for Special Areas.

Two internationally recognized sites exemplify the diverse natural environment of Turkey: Pamukkale, where mineral-rich waters have turned the area into a ‘cotton castle,’ and Cappadocia, a volcanic area where basaltic cones form impressive, inaccessible towers that have long been a place of worship and hermitage.

Law No. 2873 on National Parks, which came into force in 1983, divides Turkey’s natural heritage into four categories: 33 national parks (including Aladağlar National Park, Uludağ National Park, Beydağları Coast National Park, Lake Beyşehir, Gala Gölü, and Kazdağı and 16 [check] nature parks (including Lake Abant Nature Park, Çorum-Çatak Nature Park, Gölcük Nature Park, and Polonezköy). It further classifies 35 [check] nature reserves for the protection of the species they are home to (including Bolu Hazelnut, the Saka Gölü Nature Reserve Area/Lake Saka Nature Reserve Area, Büyük Menderes, Marmaris, and Mount Nemrut.

Natural Resources

Even though Turkey – the 61st oil producer in the world, at just over 50,000 barrels per day – depends almost entirely on its neighbors Iraq, Iran, and Russia for its energy supply, it does have significant water resources. According to the International Office for Water, Turkey’s water resources are estimated at 231.70 kms³ per year or 3,439 km³ per capita per year. Turkey is divided into 26 drainage basins, which contain around 186 billion m³ of water.

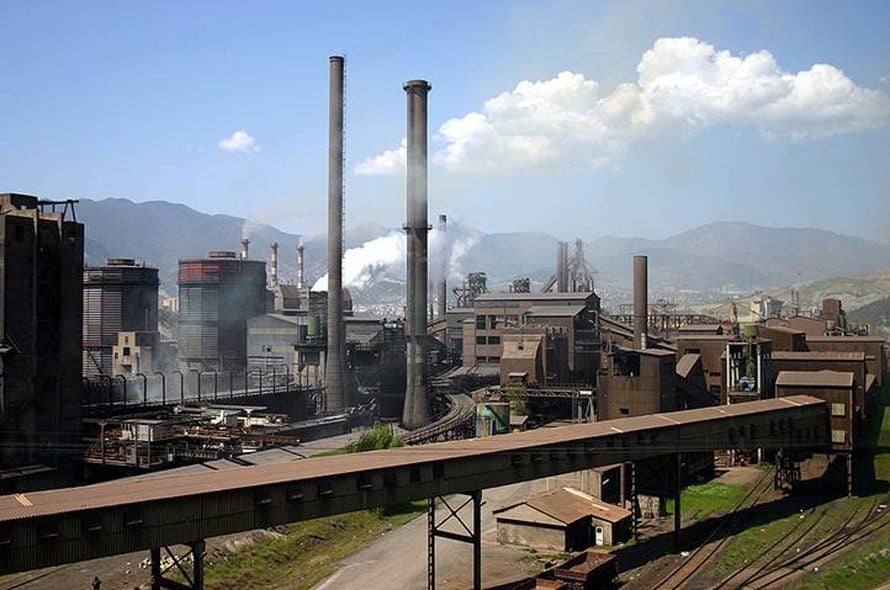

Turkey is also rich in minerals. It has about 65 percent of world boron reserves – the annual Turkish production of boron is 2.2 million tons per year – and Turkey is the tenth country in the world in total production of minerals; it produces around 60 minerals – including chromium, copper (more than 60,000 tons per year), bauxite, manganese, sulfur, nickel, marble, coal, and, marginally, gold – which produce annual revenue of USD 2.5 billion.

Environmental Issues

According to Ubifrance, the French Trade Office, the environmental situation remains worrying in Turkey, despite adopting several laws in recent years: Turkey needs about USD 70 billion to ensure compliance with international standards of environmental protection. USD 56 billion would be required to manage water that is either polluted or inadequately treated (76 percent of Turkey’s water is surface water and 24 percent groundwater). The remaining USD 14 billion would be required to eliminate hazardous industrial waste and reduce industrial pollution. According to Ubifrance, less than half of the waste is treated following Turkey’s standards and has been unable to meet.

Another cause of pollution is the massive use of coal (mostly lignite, Turkish reserves amount to 12.3 billion tons). Turkish power plants consume about 79 million tons of lignite per year (76 percent of the total amount), whereas industry and the private sector consume 10 and 14 million tons, respectively, primarily for heating. Coal distributed by municipalities as charity contributes to air pollution and reduces visibility in medium-sized cities, such as Denizli, during winter. Local governments are not the only parties responsible for the pollution; the central government does not exercise control in the excessive use of coal to develop megaprojects.

Huge water projects undertaken in the 1960s had significant ecological consequences. For example, the Southern Anatolia Project (GAP), which supplies 12 percent of the country’s electricity, has profoundly altered the landscape and threatened to submerge the ancient site of Hasankeyf. Other dam projects are currently underway in the Black Sea Region, despite intense local opposition.